BeOS

| |

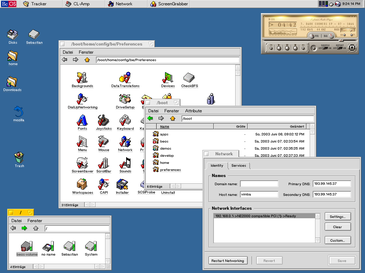

BeOS R5 | |

| Developer | Be Inc. |

|---|---|

| Written in | C++ |

| Working state | Discontinued |

| Source model | Proprietary |

| Initial release | October 3, 1995 |

| Latest release | R5 / March 28, 2000 |

| Available in | English, Japanese |

| Platforms | IA-32, PowerPC |

| Kernel type | Monolithic kernel[1][2] |

| License | Proprietary |

| Official website | beincorporated.com at the Wayback Machine (archived March 29, 2002) |

BeOS is a discontinued operating system for personal computers that was developed by Be Inc.[3] It was first written to run on their BeBox hardware which was released in 1995. BeOS was designed for powerful multitasking, heavy multithreading, and had a graphical user interface developed on the principles of clarity and a uncluttered design. The OS was later sold to OEMs, retail, and directly to users; its last version was released for free.

BeOS ran on the PowerPC platform initially and was ported to Macintosh clones, before being released for the x86 platform. It was ultimately unable to achieve a significant market share and development ended after the company's finances dwindled, with Palm acquiring the BeOS assets in 2001. Enthusiasts of BeOS have since created derivate operating systems, the most notable of which is Haiku,[4] of which its latest beta version released in 2022 still retains BeOS 5 compatibility in its x86 32-bit images.[5]

Versions and development

BeOS was the product of former Apple Computer's Jean-Louis Gassée, with the underlying philosophy of building a "media OS" capable of up-and-coming digital media[6] and multi-processors. Development began in the early 1990s, initially designed to run on AT&T Hobbit-based hardware before being modified to run on PowerPC-based processors: first Be's own BeBox system, and later Apple Computer's PowerPC Reference Platform and Common Hardware Reference Platform, with the hope that Apple would purchase or license BeOS as a replacement for its aging Mac OS.[7]

The first version of BeOS shipped with the BeBox to a limited number of developers in October 1995. It had support for analog and digital audio and MIDI streams, multiple video sources, and 3D computation.[8] Developer Release 6 (DR6) was the first officially available version. DR6 and earlier can only run on few BeBox systems today due to a bootloader update no longer able to run these older versions.

The BeOS Developer Release 7 (DR7) was released in April 1996. This new release added support for full 32-bit color graphics, "workspaces" (virtual desktops), an FTP file server and a web server and more.[9]

DR8 was released in September 1996. A new browser with MPEG and QuickTime video formats came in this release. There was also support 3D graphics based on OpenGL, and remote access.[10] BeOS was also demonstrated for the first time running on a Power Macintosh.[11]

In 1996, Apple Computer CEO Gil Amelio started negotiations to buy Be Inc., but negotiations stalled when Be CEO Jean-Louis Gassée wanted $300 million;[12] Apple was unwilling to offer any more than $125 million. Apple's board of directors decided NeXTSTEP was a better choice and purchased Steve Jobs's NeXT instead.[13]

The final developer's release introduced a file system expanded to 64-bits. BeOS Preview Release (PR1), the operating system's first for the general public, was released in mid 1997. It introduced support for AppleTalk, PostScript printers and Unicode.[14] The price for the Full Pack was $49.95. Later that year, Preview Release 2 started shipping. This version added the ability to read from and write to Macintosh's Hierarchical File System (HFS), support for systems up to 512MB RAM and improvements to the user interface.[15]

Release 3

Release 3 (R3) shipped in March 1998 (initially $69.95, later $99.95), and was the first to be ported to the Intel x86 platform (although it was also still released on PowerPC), as well as the first commercially available version of BeOS.[16] The adoption of x86 was partly due to Apple's moves, with Steve Jobs stopping the Macintosh clone market,[17] and Be's mounting debt.[18] This was followed by version 3.1, which includes additional drivers and allows reading of FAT16 file systems and supports hard drives that are 8 GB or larger. BeOS 3.2 once again brings additional drivers specifically for the x86 architecture.

Release 4

BeOS Release 4 had a claimed performance improvement of up to 30 percent. Keyboard shortcuts were changed to mimic those of Microsoft Windows[19] However it still lacked Novell NetWare support.[20] It also brought additional drivers and support for the most common SCSI controllers on the x86 platform - from Adaptec and Symbios Logic. The bootloader switched from LILO to Be's own bootman.

Version 4.5 offers experimental support for USB and PCMCIA for the first time and comes with its own media player, and unsupported graphics cards can now be addressed using a VESA driver. Also released with BeOS 4.5 was an experimental program called World O' Networking (WON), allowing Windows computers to be accessed over the network.

Release 5

In 2000, BeOS Release 5 (R5) was released. This was split between a Pro Edition, and a free version known as Personal Edition (BeOS PE) which was released for free for download over the Internet, but was also distributed on CD-ROM by third-parties.[21] BeOS PE could be started from within Microsoft Windows or Linux, and was intended to nurture consumer interest in its product and give developers something to tinker with.[22][23] Also with R5, Be released the source code of certain elements of BeOS's user interface.[24] Be CEO Gassée said in 2001 that he was open to the idea of releasing the entire operating system's source code,[25] but this never materialized.

Release 5 raised BeOS's popularity[26] but it remained commercially unsuccessful, and BeOS eventually halted following the introduction of a stripped-down version for Internet appliances, BeIA, which became the company's business focus in place of BeOS.[27] R5 would eventually be the final official release of BeOS as Be Inc. became defunct in 2001 following its sale to Palm Inc. A BeOS R5.1 "Dano", which was under development before Be's sale to Palm and included the BeOS Networking Environment (BONE) networking stack,[28] was leaked to the public shortly after the company's demise.[29]

Version history table

| Release | Date | Hardware |

|---|---|---|

| Developer Release 4 | Prototype | AT&T Hobbit |

| Developer Release 5 | October 1995 | PowerPC |

| Developer Release 6 | January 1996 | |

| Developer Release 7 | April 1996 | |

| Developer Release 8 | September 1996 | |

| Developer Release 9

(Advanced Access Preview Release) |

May 1997 | |

| Preview Release 1 | June 1997 | |

| Preview Release 2 | October 1997 | |

| Release 3 | March 1998 | PowerPC and Intel x86 |

| R3.1 | June 1998 | |

| R3.2 | July 1998 | |

| Release 4 | November 4, 1998 | |

| R4.5 ("Genki") | June 1999 | |

| Release 5 ("Maui")

Personal Edition/Pro Edition |

March 2000 | |

| R5.1 ("Dano") | Leaked | Intel x86 |

Hardware support and licensees

After the discontinuation of the BeBox in January 1997, Power Computing began bundling BeOS (on a CD-ROM for optional installation) with its line of PowerPC-based Macintosh clones. These systems could dual boot either Mac OS or BeOS, with a start-up screen offering the choice.[30] Motorola also announced in February 1997 that it would bundle BeOS with their Macintosh clones, the Motorola StarMax, along with MacOS.[31] DayStar Digital was another licensee.[32]

BeOS was naturally compatible with many Apple Macintosh computers, but it was not compatible with PowerBooks.[33]

With BeOS Release 3 on the x86 platform, the operating system was compatible with most computers that ran Microsoft Windows. Hitachi was the first major OEM that released x86 hardware with BeOS, selling the Hitachi Flora Prius line in Japan, while Fujitsu released the Silverline computers in Germany and the Nordic countries.[34] Be was unable to attract further manufacturers due to Microsoft contracts; after Be's demise in 2002, it sued Microsoft, claiming that Hitachi had been dissuaded from selling PCs loaded with BeOS. The case was eventually settled out of court for $23.25 million with no admission of liability on Microsoft's part.[35]

Architecture and features

BeOS was developed from the ground up, with a proprietary kernel, symmetric multiprocessing, preemptive multitasking and pervasive multithreading.[36] It runs in protected memory mode (which was advanced at the time), and a C++ application framework based on shared libraries and modular code.[11] Be initially offered CodeWarrior for application development,[36] and later EGCS.

Its API is object oriented. The user interface was largely multithreaded: each window ran in its own thread, relying heavily on sending messages to communicate between threads; and these concepts are reflected into the API.[37]

BeOS took advantage of modern hardware facilities such as by utilizing modular I/O bandwidth, a multithreaded graphics engine (with the OpenGL library), and a 64-bit journaling file system known as BFS (making it work with files up to a terabyte in size).[20] BeOS has partial POSIX compatibility and access to a command-line interface through Bash, although internally it is not a Unix-derived operating system. Many Unix applications were ported to the BeOS command-line interface.[38]

BeOS uses Unicode as the default encoding in the GUI, though support for input methods such as bidirectional text input was never realized.

Applications

An in-house web browser, NetPositive, was bundled with BeOS,[39] as well as an email client, BeMail,[40] and the BePoor web server. Be operated a marketplace site called BeDepot for the purchase and downloading of software including third-party, as well as a website named BeWare that listed available apps for the platform.[20] Some third-party software that were released for BeOS include Gobe Productive office suite,[20] the Mozilla project,[41][42] and multimedia apps like Cinema 4D.[43] Quake and Quake II were also officially ported to the platform, and a version of SimCity 3000 was also in the works.[44]

Reception and usage

Be did not disclose the number of BeOS users, but it was estimated to be running on between 50,000 and 100,000 computers in 1999,[34] although Release 5 was reported to have had in excess of one million downloads.[26] For a time it was viewed as a viable competitor to the classic Mac OS and Microsoft Windows, but its status as the "alternative operating system" was quickly surpassed by Linux by 1998.[45]

Reception of the operating system was largely positive citing its true and "reliable" multitasking and support for multiple processors.[46] While its market penetration was low, it did gain a niche multimedia userbase[34] and acceptance by the audio community. Consequently it was styled as a "media OS"[47] due to its well-regarded ability to handle audio and video.[48] BeOS received significant interest in Japan,[14] and was also appealing to Amiga developers and users, who were looking for a newer platform.[49]

Post-discontinuation

BeOS (and its successors, see below) have been used in media appliances, such as the Edirol DV-7 video editors from Roland Corporation, which run on top of a modified BeOS[50] and the Tunetracker Radio Automation software that used to run it on BeOS[51][52][53] and Zeta, and it was also sold as a "Station-in-a-Box" with the Zeta operating system included.[54] In 2015, Tunetracker released a Haiku distribution bundled with its broadcasting software.[55]

The Tascam SX-1 digital audio recorder runs a heavily modified version of BeOS that will only launch the recording interface software.[56] The RADAR 24, RADAR V and RADAR 6, hard disk-based, 24-track professional audio recorders from iZ Technology Corporation were based on BeOS 5.[57] Magicbox, a manufacturer of signage and broadcast display machines, uses BeOS to power their Aavelin product line.[58] Final Scratch, a 12-inch vinyl timecode record-driven DJ software and hardware system, was first developed on BeOS. The "ProFS" version was sold to a few dozen DJs prior to the 1.0 release, which ran on a Linux virtual partition.[59]

Successor projects

After BeOS came to an end, Palm created PalmSource which used parts of BeOS's multimedia framework for its failed Palm OS Cobalt product[60] (with the takeover of PalmSource, the BeOS rights now belong to Access Co.[61]). However, Palm refused on the request of BeOS users to license the operating system.[62] As a result, a few projects formed to recreate BeOS or its key elements with the eventual goal of then continuing where Be Inc. left off.

BeUnited, a BeOS oriented community, converted itself into a nonprofit organization in August 2001[63] to "define and promote open specifications for the delivery of the Open Standards BeOS-compatible Operating System (OSBOS) platform."[64]

ZETA

Immediately after Palm's purchase of Be, a German company named yellowTAB started developing Zeta based on the BeOS R5.1 codebase and released it commercially. It was later distributed by magnussoft.[65] During development by yellowTAB, the company received criticism from the BeOS community for refusing to discuss its legal position with regard to the BeOS codebase (perhaps for contractual reasons). Access Co. (which bought PalmSource, until then the holder of the intellectual property associated with BeOS) declared that yellowTAB had no right to distribute a modified version of BeOS, and magnussoft was forced to cease distribution of the operating system in 2007.[66]

Haiku (OpenBeOS)

Haiku is a complete open source reimplementation of BeOS. It was originally named OpenBeOS and its first release in 2002 was a community update.[65] Unlike Cosmoe and BlueEyedOS, it is directly compatible with BeOS applications. It is open source software. As of 2022, it was the only BeOS clone still under development, with the fourth beta (December 2022) still keeping BeOS 5 compatibility in its x86 32-bit images, with an increased number of modern drivers and GTK apps ported.[5]

BlueEyedOS

BlueEyedOS tried to create a system under LGPL based on the Linux kernel and an X server that is compatible with BeOS both optically and in terms of interfaces. Work began under the name BlueOS in 2001[67] and a demo CD was released in 2003.[68] The project was discontinued in February 2005.

Cosmoe

Cosmoe, with an interface like BeOS, was designed by Bill Hayden as an open source operating system based on the source code of AtheOS, but using the Linux kernel rather than the original AtheOS kernel as its kernel.[69] The last version 0.7.2 was released on December 17, 2004. Project author Hayden stated in an interview in December 2006 that he had not worked on the operating system for a long time and that he would welcome a successor to continue development.[70][71] In a post dated February 6, 2007, he stated that he had resumed development.[72] At the end of the same month he also announced that the release of version 0.8 was imminent,[73] however this did not happen.

ZevenOS

ZevenOS was designed to continue where Cosmoe left off.[74]

See also

References

- ^ "BeOS". Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ “BeOS’ kernel is ‘proprietary’. It uses its own kernel (small but not really micro-kernel because it includes the file system and a few other things).” —Hubert Figuière[citation needed]

- ^ Finley, Klint (May 29, 2015). "This OS Almost Made Apple an Entirely Different Company". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "About Haiku". Haiku, Inc.

- ^ a b "R1/beta4 – Release Notes". Haiku Project. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ "Technical White Paper: The Media OS". web.archive.org. May 25, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Tom (November 24, 2004). "BeOS @ MaCreate". Archived from the original on March 24, 2005. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ "Be Completes $14 million Financing". web.archive.org. May 25, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Releases BeOS Version DR7". web.archive.org. February 18, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Announces BeOS Version DR8". web.archive.org. May 25, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Be Demonstrates BeOS for PowerMac". web.archive.org. October 21, 1996. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Tom, Hormby (August 10, 2013). "The Rise and Fall of Apple's Gil Amelio". Low End Mac. Cobweb Publishing, Inc. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Owen W. Linzmayer (1999). "Apple Confidential: The Day They Almost Decided To Put Windows NT On The Mac Instead Of OS X!". Mac Speed Zone. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Be Releases BeOS Preview Release To Developers". web.archive.org. May 25, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Ships BeOS Preview Release 2". web.archive.org. October 22, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "ATPM 4.09 - Review: BeOS Release 3". www.atpm.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be boss offers OS to OEMs for free". web.archive.org. The Register. February 26, 1998. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Newsletters, Volume 3: 1998". Haiku. Be Inc. 1998. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Be, Inc. Unveils BeOS Release 4 at COMDEX Fall 98". web.archive.org. April 27, 1999. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "A desktop alternative". Forbes. January 25, 1999. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Goes Platinum with BeOS 5". web.archive.org. August 15, 2000. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Newsletters, Volume 5: 2000". Haiku. Be Inc. 2000. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "BeOS/Zeta". YellowBites. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Be Opens Source Code to Desktop Interface of BeOS 5". web.archive.org. April 12, 2001. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be getting ready to open source BeOS?". web.archive.org. The Register. February 3, 2001. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Be Goes Platinum with BeOS 5". web.archive.org. August 15, 2000. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Be Newsletters, Volume 5: 2000". Haiku. Be Inc. 2000. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Be Newsletters, Volume 5 : 2000". Haiku. Be Inc. 2000. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Jake Daniels (January 23, 2002). "More Information on the BeOS Dano Version". OSNews. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Be Newsletters, Volume 1: 1995-1996". Haiku. Be Inc. 1996. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Picarille, Lisa (February 24, 1997). "Motorola snubs NT, picks BeOS for its Mac clones". Computerworld. Vol. 31, no. 8. p. 12.

- ^ "Be Announces BeOS Support for New Multiprocessor Systems". web.archive.org. February 18, 1997. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "BeOS Ready Systems -- PowerPC". web.archive.org. January 27, 1999. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Lea, Graham (July 8, 1999). "Success expected for Be IPO". www.theregister.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Mark Berniker (September 8, 2003). "Microsoft Settles Anti-Trust Charges with Be". Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ a b https://www.gbnet.net/public/be/acrobat/AboutBe.pdf

- ^ Potrebic, Peter; Horowitz, Steve (January 1996). "Opening the BeBox". MacTech. Vol. 12, no. 1. p. 25-45.

- ^ Brown (1998)

- ^ "Ars Technica: Browsin' on BeOS - Page 1 - (9/99)". archive.arstechnica.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Ars Technica: E-Mail on the BeOS - Page 1 - (8/99)". archive.arstechnica.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Writer, CBR Staff (July 16, 1998). "BEZILLA FREE BROWSER FOR BEOS ON TRACK". Tech Monitor. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Bezilla: Mozilla for BeOS". www-archive.mozilla.org. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "CINEMA 4D goes BeOS". testou.free.fr. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "To Be Or Not To Be". Eurogamer.net. January 10, 2000. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Should you be in on Be Inc.'s IPO?". CNET. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "CNN - Meet the challengers to Windows' throne - June 12, 1998". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Orlowski, Andrew. "A Silicon Valley funeral for Be Inc". www.theregister.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Writer, Henry Norr, Chronicle Staff (March 28, 2000). "Be Inc. Tries `Open Source' System Version". CT Insider. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ CU Amiga. July 1998.

- ^ "EDIROL by Roland DV-7DL Series Digital Video Workstations". Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Hacker, Scott (May 21, 2001). "BeOS And Radio Automation". Byte.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2001. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Vernon, Tom (June 4, 2002). "TuneTracker 2 Brings Automation to All". Radio World. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Station to station". Computer Music. No. 82. Future plc. January 2005. pp. 68–73. ISSN 1463-6875.

- ^ "TuneTracker Radio Automation Software". Archived from the original on November 14, 2006. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ^ Förster, Moritz (March 17, 2015). "Alternative Betriebssysteme: Haiku als USB-Distribution" (in German). iX Magazin. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Professional Audio Coming to Haiku?". Haikuware. September 6, 2011. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "iZ RADAR 24". Archived from the original on December 27, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ^ Jay Ankeney (May 1, 2006). "Technology Showcase: Digital Signage Hardware". Digital Content Producer. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ^ Peter Kirn (April 28, 2008). "Ni Ends Legal Dispute Over Traktor Scratch; Digital Vinyl's Twisty, Turny History". Create Digital Music. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ PalmSource Introduces Palm OS Cobalt, PalmSource press release, February 10, 2004. Archived July 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ACCESS Completes Acquisition of PalmSource, ACCESS press release, November 14, 2005. Archived January 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Orlowski, Andrew. "Palm scuppers BeOS co-op hopes". www.theregister.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "BeUnited - A global initiative aimed at professionally developing and marketing the BeOS". web.archive.org. February 6, 2002. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "beunited.org - Open Standards BeOS-compatible Operating Systems". web.archive.org. April 8, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b White, Bradford Morgan. "'Be' is nice. End of story". www.abortretry.fail. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Zeta Operating System". Operating System.org. October 14, 2013. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ blueos.free.fr/news.html

- ^ "BlueEyedOS Demo/Test CD Now Available – OSnews". www.osnews.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Interview with Cosmoe's Bill Hayden – OSnews". www.osnews.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "IsComputerOn - Contact with Bill. (updated)". web.archive.org. February 2, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Cosmoe Developer Seeks Successor – OSnews". www.osnews.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Topica Email List Directory". web.archive.org. February 4, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Topica Email List Directory". web.archive.org. February 4, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "ZevenOS - Does it recapture the flavor of BeOS? | Linux Journal". www.linuxjournal.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

Further reading

- Brown, Martin C. (1998). BeOS: Porting UNIX Applications. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1558605329.

- Bortman, Henry; Pittelkau, Jeff (January 1997). "Plan Be". MacUser. Vol. 13, no. 1. p. 64-72.

External links

- The Dawn of Haiku, by Ryan Leavengood, IEEE Spectrum May 2012, p 40–43,51-54.

- Mirror of the old www.be.com site Other Mirror of the old www.be.com site

- BeOS Celebrating Ten Years

- BeGroovy Archived September 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine A blog dedicated to all things BeOS

- BeOS: The Mac OS X might-have-been, reghardware.co.uk

- Programming the Be Operating System: An O'Reilly Open Book (out of print, but can be downloaded)

- BeOS Developer Video on YouTube

- U.S. Trademark 78,558,039 (BeOS)