-

Integral Operators in b-Metric Spaces

-

Automatic Voltage Regulator Betterment Based on a New Fuzzy FOPI+FOPD Tuned by TLBO

-

Relating the Morphology of Bipolar Neurons to Fractal Dimension

-

An Iterative Method to Approximate a Common Fixed Point: Application to Fractal Functi

-

Fractal-Based Robotic Trading Strategies Using Detrended Fluctuation Analysis and Fractional Derivatives: A Case Study in the Energy Market

Journal Description

Fractal and Fractional

Fractal and Fractional

is an international, scientific, peer-reviewed, open access journal of fractals and fractional calculus and their applications in different fields of science and engineering published monthly online by MDPI.

- Open Access— free for readers, with article processing charges (APC) paid by authors or their institutions.

- High Visibility: indexed within Scopus, SCIE (Web of Science), Inspec, and other databases.

- Journal Rank: JCR - Q1 (Mathematics, Interdisciplinary Applications) / CiteScore - Q1 (Analysis)

- Rapid Publication: manuscripts are peer-reviewed and a first decision is provided to authors approximately 23.7 days after submission; acceptance to publication is undertaken in 2.7 days (median values for papers published in this journal in the second half of 2024).

- Recognition of Reviewers: reviewers who provide timely, thorough peer-review reports receive vouchers entitling them to a discount on the APC of their next publication in any MDPI journal, in appreciation of the work done.

Impact Factor:

3.6 (2023);

5-Year Impact Factor:

3.5 (2023)

Latest Articles

New Class of Complex Models of Materials withPiezoelectric Properties with Differential Constitutive Relations of Fractional Order: An Overview

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 170; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030170 - 11 Mar 2025

Abstract

Rheological complex models of various elastoviscous and viscoelastic fractional-type substances with polarized piezoelectric properties are of interest due to the widespread use of viscoelastic–plastic bodies under loading. The word “overview” used in the title means and corresponds to the content of the manuscript

[...] Read more.

Rheological complex models of various elastoviscous and viscoelastic fractional-type substances with polarized piezoelectric properties are of interest due to the widespread use of viscoelastic–plastic bodies under loading. The word “overview” used in the title means and corresponds to the content of the manuscript and aims to emphasize that it presents an overview of a new class of complex rheological models of the fractional type of ideal elastoviscous, as well as viscoelastic, materials with piezoelectric properties. Two new elementary rheological elements were introduced: a rheological basic Newton’s element of ideal fluid fractional type and a basic Faraday element of ideal elastic material with the property of polarization under mechanical loading and piezoelectric properties. By incorporating these newly introduced rheological elements into classical complex rheological models, a new class of complex rheological models of materials with piezoelectric properties described by differential fractional-order constitutive relations was obtained. A set of seven new complex rheological models of materials are presented with appropriate structural formulas. Differential constitutive relations of the fractional order, which contain differential operators of the fractional order, are composed. The seven new complex models describe the properties of ideal new materials, which can be elastoviscous solids or viscoelastic fluids. The purpose of the work is to make a theoretical contribution by introducing, designing, and presenting a new class of rheological complex models with appropriate differential constitutive relations of the fractional order. These theoretical results can be the basis for further scientific and applied research. It is especially important to point out the possibility that these models containing a Faradаy element can be used to collect electrical energy for various purposes.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Complexity, Fractality and Fractional Dynamics Applied to Science and Engineering)

Open AccessArticle

Optimal Coordination of Directional Overcurrent Relays Using an Innovative Fractional-Order Derivative War Algorithm

by

Bakht Muhammad Khan, Abdul Wadood, Herie Park, Shahbaz Khan and Husan Ali

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 169; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030169 - 11 Mar 2025

Abstract

Efficient coordination of directional overcurrent relays (DOCRs) is vital for maintaining the stability and reliability of electrical power systems (EPSs). The task of optimizing DOCR coordination in complex power networks is modeled as an optimization problem. This study aims to enhance the performance

[...] Read more.

Efficient coordination of directional overcurrent relays (DOCRs) is vital for maintaining the stability and reliability of electrical power systems (EPSs). The task of optimizing DOCR coordination in complex power networks is modeled as an optimization problem. This study aims to enhance the performance of protection systems by minimizing the cumulative operating time of DOCRs. This is achieved by effectively synchronizing primary and backup relays while ensuring that coordination time intervals (CTIs) remain within predefined limits (0.2 to 0.5 s). A novel optimization strategy, the fractional-order derivative war optimizer (FODWO), is proposed to address this challenge. This innovative approach integrates the principles of fractional calculus (FC) into the conventional war optimization (WO) algorithm, significantly improving its optimization properties. The incorporation of fractional-order derivatives (FODs) enhances the algorithm’s ability to navigate complex optimization landscapes, avoiding local minima and achieving globally optimal solutions more efficiently. This leads to the reduced cumulative operating time of DOCRs and improved reliability of the protection system. The FODWO method was rigorously tested on standard EPSs, including IEEE three, eight, and fifteen bus systems, as well as on eleven benchmark optimization functions, encompassing unimodal and multimodal problems. The comparative analysis demonstrates that incorporating fractional-order derivatives (FODs) into the WO enhances its efficiency, enabling it to achieve globally optimal solutions and reduce the cumulative operating time of DOCRs by 3%, 6%, and 3% in the case of a three, eight, and fifteen bus system, respectively, compared to the traditional WO algorithm. To validate the effectiveness of FODWO, comprehensive statistical analyses were conducted, including box plots, quantile–quantile (QQ) plots, the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF), and minimal fitness evolution across simulations. These analyses confirm the robustness, reliability, and consistency of the FODWO approach. Comparative evaluations reveal that FODWO outperforms other state-of-the-art nature-inspired algorithms and traditional optimization methods, making it a highly effective tool for DOCR coordination in EPSs.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Modeling, Optimization, and Control of Fractional-Order Neural Networks and Nonlinear Systems)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>IEEE 3 bus electrical power network with DOCR coordination.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Proposed methodology (FODWO) workflow.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Attack strategy in WSO.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE three bus test system.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Convergence graph (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Percentage net time gain obtained by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> for DOCRs obtained for different algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE three-bus system (test system 1): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE eight-bus configuration.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Convergence characteristic for WO and FODWO for IEEE eight-bus system.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Percentage net time gain obtained by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> <mo> </mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> of DOCRs obtained for different algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE eight-bus system (test system 2): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE 15-bus configuration.</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Convergence characteristic for WO and FODWO for IEEE 15-bus system.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 19

<p>Percentage net time gain by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 20

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> of DOCRs for different algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 21

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE fifteen-bus system (test system 3): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">

<p>IEEE 3 bus electrical power network with DOCR coordination.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Proposed methodology (FODWO) workflow.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Attack strategy in WSO.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE three bus test system.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Convergence graph (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Percentage net time gain obtained by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> for DOCRs obtained for different algorithms (test system 1).</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE three-bus system (test system 1): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE eight-bus configuration.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Convergence characteristic for WO and FODWO for IEEE eight-bus system.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Percentage net time gain obtained by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> <mo> </mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> of DOCRs obtained for different algorithms (test system 2).</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE eight-bus system (test system 2): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Single-line diagram of IEEE 15-bus configuration.</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Convergence characteristic for WO and FODWO for IEEE 15-bus system.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Total net gain by FODWO compared to other algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 19

<p>Percentage net time gain by FODWO against other algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 20

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mrow> <mi>T</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>o</mi> <mi>p</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> of DOCRs for different algorithms (test system 3).</p> Full article ">Figure 21

<p>Statistical evaluation for IEEE fifteen-bus system (test system 3): (<b>a</b>) CDF, (<b>b</b>) boxplot, (<b>c</b>) minimum fitness, and (<b>d</b>) quantile-quantile plot.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Pythagorean Fuzzy Overlap Functions and Corresponding Fuzzy Rough Sets for Multi-Attribute Decision Making

by

Yongjun Yan, Jingqian Wang and Xiaohong Zhang

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 168; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030168 - 11 Mar 2025

Abstract

As a non-associative connective in fuzzy logic, the analysis and research of overlap functions have been extended to many generalized cases, such as interval-valued and intuitionistic fuzzy overlap functions (IFOFs). However, overlap functions face challenges in the Pythagorean fuzzy (PF) environment. This paper

[...] Read more.

As a non-associative connective in fuzzy logic, the analysis and research of overlap functions have been extended to many generalized cases, such as interval-valued and intuitionistic fuzzy overlap functions (IFOFs). However, overlap functions face challenges in the Pythagorean fuzzy (PF) environment. This paper first extends overlap functions to the PF domain by proposing PF overlap functions (PFOFs), discussing their representable forms, and providing a general construction method. It then introduces a new PF similarity measure which addresses issues in existing measures (e.g., the inability to measure the similarity of certain PF numbers) and demonstrates its effectiveness through comparisons with other methods, using several examples in fractional form. Based on the proposed PFOFs and their induced residual implication, new generalized PF rough sets (PFRSs) are constructed, which extend the PFRS models. The relevant properties of their approximation operators are explored, and they are generalized to the dual-domain case. Due to the introduction of hesitation in IF and PF sets, the approximate accuracy of classical rough sets is no longer applicable. Therefore, a new PFRS approximate accuracy is developed which generalizes the approximate accuracy of classical rough sets and remains applicable to the classical case. Finally, three multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) algorithms based on PF information are proposed, and their effectiveness and rationality are validated through examples, making them more flexible for solving MCDM problems in the PF environment.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Fractal and Fractional Statistics for Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, and Quantum Computing, 2nd Edition)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Relationships among related fuzzy rough sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Difference between rough sets and classical sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Images with different <math display="inline"><semantics> <mi mathvariant="script">FS</mi> </semantics></math> values.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mi mathvariant="script">FS</mi> </semantics></math> values of elements in different sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Ranking results between different methods.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Ranking results in different situations.</p> Full article ">

<p>Relationships among related fuzzy rough sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Difference between rough sets and classical sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Images with different <math display="inline"><semantics> <mi mathvariant="script">FS</mi> </semantics></math> values.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mi mathvariant="script">FS</mi> </semantics></math> values of elements in different sets.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Ranking results between different methods.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Ranking results in different situations.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

An Improved Numerical Scheme for 2D Nonlinear Time-Dependent Partial Integro-Differential Equations with Multi-Term Fractional Integral Items

by

Fan Ouyang, Hongyan Liu and Yanying Ma

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 167; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030167 - 11 Mar 2025

Abstract

This paper is dedicated to investigating a highly accurate numerical solution for a class of 2D nonlinear time-dependent partial integro-differential equations with multi-term fractional integral items. These integrals are weakly singular with respect to time, which are handled using the product integration rule

[...] Read more.

This paper is dedicated to investigating a highly accurate numerical solution for a class of 2D nonlinear time-dependent partial integro-differential equations with multi-term fractional integral items. These integrals are weakly singular with respect to time, which are handled using the product integration rule on graded meshes to compensate for the influence generated by the initial weak singular nature of the exact solution. The temporal derivative is approximated by a generalized Crank–Nicolson difference scheme, while the nonlinear term is approximated by a linearized method. Furthermore, the stability and convergence of the derived time semi-discretization scheme are strictly proved by revising the finite discrete parameters. Meanwhile, the differential matrices of the spatial high-order derivatives based on barycentric rational interpolation are utilized to obtain the fully discrete scheme. Finally, the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed method are validated by means of several numerical experiments.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Recent Advances in the Spatial and Temporal Discretizations of Fractional PDEs, Second Edition)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>The symbols of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>−</mo> <mn>2</mn> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>+</mo> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>2</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> </mrow> </semantics></math> with <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>α</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mstyle scriptlevel="0" displaystyle="true"> <mfrac> <mi>i</mi> <mn>10</mn> </mfrac> </mstyle> <mo>,</mo> <mspace width="4pt"/> <mi>i</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mn>2</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mo>…</mo> <mo>,</mo> <mn>9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The symbols of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>−</mo> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> </mrow> </semantics></math> with <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>α</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mstyle scriptlevel="0" displaystyle="true"> <mfrac> <mi>i</mi> <mn>10</mn> </mfrac> </mstyle> <mo>,</mo> <mspace width="4pt"/> <mi>i</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mn>2</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mo>…</mo> <mo>,</mo> <mn>9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Errors for varying numbers of interpolation nodes, in Example 1.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Comparison between the BRI and spectral method in Example 1.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Errors for varying numbers of interpolation nodes in Example 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Comparison between the BRI and spectral method in Example 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.2</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.5</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.2</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.8</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.5</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.8</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">

<p>The symbols of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>−</mo> <mn>2</mn> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>+</mo> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>2</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> </mrow> </semantics></math> with <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>α</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mstyle scriptlevel="0" displaystyle="true"> <mfrac> <mi>i</mi> <mn>10</mn> </mfrac> </mstyle> <mo>,</mo> <mspace width="4pt"/> <mi>i</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mn>2</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mo>…</mo> <mo>,</mo> <mn>9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The symbols of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> <mo>−</mo> <msubsup> <mi>b</mi> <mrow> <mi>n</mi> <mo>,</mo> <mi>n</mi> <mo>−</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <mi>α</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </msubsup> </mrow> </semantics></math> with <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>α</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mstyle scriptlevel="0" displaystyle="true"> <mfrac> <mi>i</mi> <mn>10</mn> </mfrac> </mstyle> <mo>,</mo> <mspace width="4pt"/> <mi>i</mi> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mn>2</mn> <mo>,</mo> <mo>…</mo> <mo>,</mo> <mn>9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Errors for varying numbers of interpolation nodes, in Example 1.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Comparison between the BRI and spectral method in Example 1.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Errors for varying numbers of interpolation nodes in Example 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Comparison between the BRI and spectral method in Example 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.2</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.5</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.2</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.8</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Referenced exact solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.5</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>α</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.8</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math> in Example 3.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

A Generalization of the Fractional Stockwell Transform

by

Subbiah Lakshmanan, Rajakumar Roopkumar and Ahmed I. Zayed

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 166; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030166 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

This paper presents a generalized fractional Stockwell transform (GFST), extending the classical Stockwell transform and fractional Stockwell transform, which are widely used tools in time–frequency analysis. The GFST on

This paper presents a generalized fractional Stockwell transform (GFST), extending the classical Stockwell transform and fractional Stockwell transform, which are widely used tools in time–frequency analysis. The GFST on

Open AccessArticle

Effect of Particle Size on Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Deep Siliceous Shales in Southern Sichuan, China, Measured Using Small-Angle Neutron Scattering and Low-Pressure Nitrogen Adsorption

by

Hongming Zhan, Xizhe Li, Zhiming Hu, Liqing Chen, Weijun Shen, Wei Guo, Weikang He and Yuhang Zhou

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 165; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030165 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Granular samples are often used to characterize the pore structure of shale. To systematically analyze the influence of particle size on pore characteristics, case studies were performed on two groups of organic-rich deep shale samples. Multiple methods, including small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), low-pressure

[...] Read more.

Granular samples are often used to characterize the pore structure of shale. To systematically analyze the influence of particle size on pore characteristics, case studies were performed on two groups of organic-rich deep shale samples. Multiple methods, including small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), low-pressure nitrogen gas adsorption (LP-N2GA), low-pressure carbon dioxide gas adsorption (LP-CO2GA), and XRD analysis, were adopted to investigate how the crushing process would affect pore structure parameters and the fractal features of deep shale samples. The research indicates that with the decrease in particle size, the measurements from nitrogen adsorption and SANS experiments significantly increase, with relative effects reaching 95.09% and 51.27%, respectively. However, the impact on carbon dioxide adsorption measurements is minor, with a maximum of only 8.97%. This suggests that the comminution process primarily alters the macropore structure, with limited influence on the micropores. Since micropores contribute the majority of the specific surface area in deep shale, the effect of particle size variation on the specific surface area is negligible, averaging only 16.52%. Shales exhibit dual-fractal characteristics. The distribution range of the mass fractal dimension of the experimental samples is 2.658–2.961, which increases as the particle size decreases. The distribution range of the surface fractal dimension is 2.777–2.834, which decreases with the decrease in particle size.

Full article

Open AccessArticle

Fixed-Point Results in Fuzzy S-Metric Space with Applications to Fractals and Satellite Web Coupling Problem

by

Ilyas Khan, Muhammad Shaheryar, Fahim Ud Din, Umar Ishtiaq and Ioan-Lucian Popa

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 164; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030164 - 8 Mar 2025

Abstract

In this manuscript, we introduce the concept of fuzzy S-metric spaces and study some of their characteristics. We prove a fixed-point theorem for a self-mapping on a complete fuzzy S-metric space. To illustrate the versatility of our new ideas and related fixed-point theorems,

[...] Read more.

In this manuscript, we introduce the concept of fuzzy S-metric spaces and study some of their characteristics. We prove a fixed-point theorem for a self-mapping on a complete fuzzy S-metric space. To illustrate the versatility of our new ideas and related fixed-point theorems, we give examples to illustrate their use in a variety of domains, including fractal formation. These examples illustrate how the fuzzy S-contraction can be applied to iterated function systems, enabling the exploration of fractal forms under diverse contractive conditions. In addition, we solve the satellite web coupling problem by employing this coherent framework.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Metric Spaces with Its Application to Fractional Differential Equations)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>W</mi> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>3</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>4</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>W</mi> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>3</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p><math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msup> <mi>W</mi> <mn>4</mn> </msup> <mrow> <mo>(</mo> <msub> <mi mathvariant="script">L</mi> <mi>o</mi> </msub> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Analysis of Multifractal Characteristics and Detrended Cross-Correlation of Conventional Logging Data Regarding Igneous Rocks

by

Shiyao Wang, Dan Mou, Xinghua Qi and Zhuwen Wang

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 163; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030163 - 7 Mar 2025

Abstract

In the current context of the global energy landscape, China is facing a growing challenge in oil and gas exploration and development. It is difficult to evaluate the log data because of the lithological composition of igneous rocks, which displays an unparalleled degree

[...] Read more.

In the current context of the global energy landscape, China is facing a growing challenge in oil and gas exploration and development. It is difficult to evaluate the log data because of the lithological composition of igneous rocks, which displays an unparalleled degree of complexity and unpredictability. Against this backdrop, this study deploys advanced multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MF-DFA) to comprehensively analyze key parameters within igneous rock logging data, including natural gamma-ray logging, resistivity logging, compensated neutron logging, and acoustic logging. The results unequivocally demonstrate that these logging data possess distinct multifractal characteristics. This multifractality serves as a powerful tool to elucidate the inherent complexity, heterogeneity, and structural and property variations in igneous rocks caused by diverse geological processes and environmental changes during their formation and evolution, which is crucial for understanding the subsurface reservoir behavior. Subsequently, through a series of rearrangement sequences and the replacement sequence on the original logging data, we identify that the probability density function and long-range correlation are the fundamental sources of the observed multifractality. These findings contribute to a deeper theoretical understanding of the data-generating mechanisms within igneous rock formations. Finally, multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis (MF-DCCA) is employed to explore the cross-correlations among different types of igneous rock logging data. We uncover correlations among different igneous rocks’ logging data. These parameters exhibit different properties. There are negative long-range correlations between natural gamma-ray logging and resistivity logging, natural gamma-ray logging and compensated neutron logging in basalt, and resistivity logging and compensated neutron logging in diabase. The logging data on other igneous rocks have long-range correlations. These correlation results are of great significance as they provide solid data support for the formulation of oil and gas exploration and development plans.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics in Unconventional Oil and Gas Reservoirs)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>The flowchart of the multifractal analysis.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Logging deployment map of the middle and southern sections in the eastern sag of the Liaohe Basin.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Multifractality of DEN data regarding all igneous rocks.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Multifractal analysis of basalt logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Multifractal analysis of diabase logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Multifractal analysis of gabbro logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Multifractal analysis of tuff logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Multifractal analysis of magmatic breccia logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Results of multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis. (<b>a</b>) Basalt; (<b>b</b>) diabase; (<b>c</b>) gabbro; (<b>d</b>) tuff; (<b>e</b>) magmatic breccia.</p> Full article ">

<p>The flowchart of the multifractal analysis.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Logging deployment map of the middle and southern sections in the eastern sag of the Liaohe Basin.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Multifractality of DEN data regarding all igneous rocks.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Multifractal analysis of basalt logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Multifractal analysis of diabase logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Multifractal analysis of gabbro logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Multifractal analysis of tuff logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Multifractal analysis of magmatic breccia logging data. (<b>a</b>) Generalized Hurst index; (<b>b</b>) scale index; (<b>c</b>) multifractal spectrum.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Results of multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis. (<b>a</b>) Basalt; (<b>b</b>) diabase; (<b>c</b>) gabbro; (<b>d</b>) tuff; (<b>e</b>) magmatic breccia.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Time-Varying Market Efficiency: A Focus on Crude Oil and Commodity Dynamics

by

Young-Sung Kim, Do-Hyeon Kim, Dong-Jun Kim and Sun-Yong Choi

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 162; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030162 - 6 Mar 2025

Abstract

This study investigated market efficiency across 20 major commodity assets, including crude oil, utilizing fractal analysis. Additionally, a rolling window approach was employed to capture the time-varying nature of efficiency in these markets. A Granger causality test was applied to assess the influence

[...] Read more.

This study investigated market efficiency across 20 major commodity assets, including crude oil, utilizing fractal analysis. Additionally, a rolling window approach was employed to capture the time-varying nature of efficiency in these markets. A Granger causality test was applied to assess the influence of crude oil on other commodities. Key findings revealed significant inefficiencies in RBOB(Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenated Blending) Gasoline, Palladium, and Brent Crude Oil, largely driven by geopolitical risks that exacerbated supply–demand imbalances. By contrast, Copper, Kansas Wheat, and Soybeans exhibited greater efficiency because of their stable market dynamics. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the time-varying nature of efficiency, with short-term volatility causing price fluctuations. Geopolitical events such as the Russia–Ukraine War exposed some commodities to shocks, while others remained resilient. Brent Crude Oil was a key driver of market inefficiency. Our findings align with Fractal Fractional (FF) concepts. The MF-DFA method revealed self-similarity in market prices, while inefficient markets exhibited long-memory effects, challenging the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Additionally, rolling window analysis captured evolving market efficiency, influenced by external shocks, reinforcing the relevance of fractal fractional models in financial analysis. Furthermore, these findings can help traders, policymakers, and researchers, by highlighting Brent Crude Oil as a key market indicator and emphasizing the need for risk management and regulatory measures.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Fractal and Multifractal Analysis in Econometric Models and Empirical Finance)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Return time series for all selected commodity assets.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The curve of the multifractal fluctuation function <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>F</mi> <mi>q</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>s</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> compared to <span class="html-italic">s</span> in a log−log plot of the average return for all the indices in developed countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Generalized Hurst exponents <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>h</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>q</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> of the index return in developed countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>The multifractal spectra of each index return in frontier countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Descending order <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> and the commodity assets.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>The dynamics of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> using a rolling window for developed countries. The window length was 400 days.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Scatter plot of the GPR index and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> series.</p> Full article ">

<p>Return time series for all selected commodity assets.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The curve of the multifractal fluctuation function <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>F</mi> <mi>q</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>s</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> compared to <span class="html-italic">s</span> in a log−log plot of the average return for all the indices in developed countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Generalized Hurst exponents <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>h</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>q</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> of the index return in developed countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>The multifractal spectra of each index return in frontier countries.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Descending order <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> and the commodity assets.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>The dynamics of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> using a rolling window for developed countries. The window length was 400 days.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Scatter plot of the GPR index and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mo>Δ</mo> <mi>α</mi> </mrow> </semantics></math> series.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

A Model-Free Fractional-Order Composite Control Strategy for High-Precision Positioning of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor

by

Peng Gao, Chencheng Zhao, Huihui Pan and Liandi Fang

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 161; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030161 - 5 Mar 2025

Abstract

►▼

Show Figures

This paper introduces a novel model-free fractional-order composite control methodology specifically designed for precision positioning in permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) drives. The proposed framework ingeniously combines a composite control architecture, featuring a super twisting double fractional-order differential sliding mode controller (STDFDSMC) synergistically

[...] Read more.

This paper introduces a novel model-free fractional-order composite control methodology specifically designed for precision positioning in permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) drives. The proposed framework ingeniously combines a composite control architecture, featuring a super twisting double fractional-order differential sliding mode controller (STDFDSMC) synergistically integrated with a complementary extended state observer (CESO). The STDFDSMC incorporates an innovative fractional-order double differential sliding mode surface, engineered to deliver superior robustness, enhanced flexibility, and accelerated convergence rates, while simultaneously addressing potential singularity issues. The CESO is implemented to achieve precise estimation and compensation of both intrinsic and extrinsic disturbances affecting PMSM drive systems. Through rigorous application of Lyapunov stability theory, we provide a comprehensive theoretical validation of the closed-loop system’s convergence stability under the proposed control paradigm. Extensive comparative analyses with conventional control methodologies are conducted to substantiate the efficacy of our approach. The comparative results conclusively demonstrate that the proposed control method represents a significant advancement in PMSM drive performance optimization, offering substantial improvements over existing control strategies.

Full article

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>(<b>a</b>) The field oriented control of the PMSM control system; (<b>b</b>) The detailed block diagram of the proposed STDFDSMC.</p> Full article ">Figure 1 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) The field oriented control of the PMSM control system; (<b>b</b>) The detailed block diagram of the proposed STDFDSMC.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the traditional differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 11 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the traditional differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the double fractional-order differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the proposed STDFDSMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">

<p>(<b>a</b>) The field oriented control of the PMSM control system; (<b>b</b>) The detailed block diagram of the proposed STDFDSMC.</p> Full article ">Figure 1 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) The field oriented control of the PMSM control system; (<b>b</b>) The detailed block diagram of the proposed STDFDSMC.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with small load.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with large load.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the traditional differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the double fractional-order differential SMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve of PMSM under the proposed STDFDSMC with step signal; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the traditional differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 11 Cont.

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the traditional differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the double fractional-order differential SMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>(<b>a</b>) Position response curve rejecting external disturbance under the proposed STDFDSMC; (<b>b</b>) Detailed view of the image (<b>a</b>).</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Applying a Gain Scheduled Fractional Order Proportional Integral and Derivative Controller to a Quadratic Buck Converter

by

German Ardul Munoz Hernandez, Jose Fermi Guerrero-Castellanos and Rafael Antonio Acosta-Rodriguez

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 160; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030160 - 5 Mar 2025

Abstract

This work presents a fractional order Proportional Integral and Derivative controller with adaptation characteristics in the control parameters depending on the required output, gain scheduling fractional order PID (GS-FO-PID). The fractional order PID is applied to the voltage control of a DC–DC buck

[...] Read more.

This work presents a fractional order Proportional Integral and Derivative controller with adaptation characteristics in the control parameters depending on the required output, gain scheduling fractional order PID (GS-FO-PID). The fractional order PID is applied to the voltage control of a DC–DC buck quadratic converter (QBC). The DC–DC buck quadratic converter is designed to operate at 12 V, although in the simulation tests, the output voltage ranges from 5 to 36 V. The performance of the GS-FO-PID is compared with the one from a classic PID. The GS-FO-PID presents better performance when the reference voltage is changed. In the same way, the behavior of the converter with the reference fixed to 12 V output is analyzed with load changes; for this case, the amplitude value of the ripple when the converter is driven by the GS-FO-PID almost has no variation.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Applications of Fractional-Order Systems to Automatic Control)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Quadratic buck converter. (<b>a</b>) ON state. (<b>b</b>) OFF state.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Schematic diagram of the GS-PID controller.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Simulink<sup>©</sup> models used to evaluate the controllers.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Details of the outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>Details of the outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change with the initial conditions equal to zero.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Response of the quadratic buck converter with a load change.</p> Full article ">

<p>Quadratic buck converter. (<b>a</b>) ON state. (<b>b</b>) OFF state.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Schematic diagram of the GS-PID controller.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Simulink<sup>©</sup> models used to evaluate the controllers.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Details of the outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>Details of the outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Outputs of the quadratic buck converter under different controllers with voltage change with the initial conditions equal to zero.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Response of the quadratic buck converter with a load change.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Study on Surface Roughness and True Fracture Energy of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using Fringe Projection Technology

by

Meiling Dai, Weiyi Hu, Chengge Hu, Xirui Wang, Jiyu Deng and Jincai Chen

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 159; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030159 - 4 Mar 2025

Abstract

This paper investigates the fracture surfaces and fracture performance of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) using fringe projection technology. This non-contact, point-by-point, and full-field scanning technique allows precise measurement of RAC’s fracture surface characteristics. This research focuses on the effects of recycled aggregate replacement

[...] Read more.

This paper investigates the fracture surfaces and fracture performance of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) using fringe projection technology. This non-contact, point-by-point, and full-field scanning technique allows precise measurement of RAC’s fracture surface characteristics. This research focuses on the effects of recycled aggregate replacement rate, water-to-binder (w/b) ratio, and maximum aggregate size on RAC’s fracture properties. A decrease in the w/b ratio significantly reduces surface roughness (Rs) and fractal dimension (D), due to increased cement mortar bond strength at lower w/b ratios, causing cracks to propagate through aggregates and resulting in smoother fracture surfaces. At higher w/b ratios (0.8 and 0.6), both surface roughness and fractal dimension decrease as the recycled aggregate replacement rate increases. At a w/b ratio of 0.4, these parameters are not significantly affected by the replacement rate, indicating stronger cement mortar. Larger aggregates result in slightly higher surface roughness compared to smaller aggregates, due to more pronounced interface changes. True fracture energy is consistently lower than nominal fracture energy, with the difference increasing with higher recycled aggregate replacement rates and larger aggregate sizes. It increases as the w/b ratio decreases. These findings provide a scientific basis for optimizing RAC mix design, enhancing its fracture performance and supporting its practical engineering applications.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Fracture Analysis of Materials Based on Fractal Nature)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Raw materials.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Specimen curing site.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Cube compressive strength test: (<b>a</b>) the specimens; (<b>b</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Cube splitting tensile test: (<b>a</b>) the specimens; (<b>b</b>) the bracket; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>The fracture test: (<b>a</b>) dimensions; (<b>b</b>) specimens; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>The fracture test: (<b>a</b>) dimensions; (<b>b</b>) specimens; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Microscopic test: (<b>a</b>) SEM; (<b>b</b>) ion sputtering machine; (<b>c</b>) specimen after gold coating.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Concrete surface measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 7 Cont.

<p>Concrete surface measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Standard cylinder measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Fracture surface morphology for the maximin aggregate size of 31.5 mm.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Microstructure of concrete obtained from SEM: (<b>a</b>) NC; (<b>b</b>) RAC.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Fracture paths in (<b>a</b>) NC; (<b>b</b>) RAC.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different Ra: (<b>a</b>) roughness (<b>b</b>) fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 13 Cont.

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different Ra: (<b>a</b>) roughness (<b>b</b>) fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Fracture surface morphology for different maximin aggregate sizes.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>The relationship between surface roughness and fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Fracture energy obtained from different methods [<a href="#B8-fractalfract-09-00159" class="html-bibr">8</a>,<a href="#B20-fractalfract-09-00159" class="html-bibr">20</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Effect of w/b ratio on the true fracture energy for different RA contents.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Effect of recycled aggregate replacement rate on the true fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 18 Cont.

<p>Effect of recycled aggregate replacement rate on the true fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 19

<p>Effect of maximum aggregate size on the fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">

<p>Raw materials.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Specimen curing site.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Cube compressive strength test: (<b>a</b>) the specimens; (<b>b</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Cube splitting tensile test: (<b>a</b>) the specimens; (<b>b</b>) the bracket; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>The fracture test: (<b>a</b>) dimensions; (<b>b</b>) specimens; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>The fracture test: (<b>a</b>) dimensions; (<b>b</b>) specimens; (<b>c</b>) loading.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Microscopic test: (<b>a</b>) SEM; (<b>b</b>) ion sputtering machine; (<b>c</b>) specimen after gold coating.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Concrete surface measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 7 Cont.

<p>Concrete surface measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Standard cylinder measurement.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Fracture surface morphology for the maximin aggregate size of 31.5 mm.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Microstructure of concrete obtained from SEM: (<b>a</b>) NC; (<b>b</b>) RAC.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Fracture paths in (<b>a</b>) NC; (<b>b</b>) RAC.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different Ra: (<b>a</b>) roughness (<b>b</b>) fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 13 Cont.

<p>Roughness and fractal dimension for different Ra: (<b>a</b>) roughness (<b>b</b>) fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Fracture surface morphology for different maximin aggregate sizes.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>The relationship between surface roughness and fractal dimension.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Fracture energy obtained from different methods [<a href="#B8-fractalfract-09-00159" class="html-bibr">8</a>,<a href="#B20-fractalfract-09-00159" class="html-bibr">20</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Effect of w/b ratio on the true fracture energy for different RA contents.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Effect of recycled aggregate replacement rate on the true fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 18 Cont.

<p>Effect of recycled aggregate replacement rate on the true fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">Figure 19

<p>Effect of maximum aggregate size on the fracture energy for different w/b ratios.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Hyers–Ulam Stability of Fractal–Fractional Computer Virus Models with the Atangana–Baleanu Operator

by

Mohammed Althubyani and Sayed Saber

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 158; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030158 - 4 Mar 2025

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to propose a fractal–fractional-order for computer virus propagation dynamics, in accordance with the Atangana–Baleanu operator. We examine the existence of solutions, as well as the Hyers–Ulam stability, uniqueness, non-negativity, positivity, and boundedness based on the fractal–fractional sense.

[...] Read more.

The purpose of this paper is to propose a fractal–fractional-order for computer virus propagation dynamics, in accordance with the Atangana–Baleanu operator. We examine the existence of solutions, as well as the Hyers–Ulam stability, uniqueness, non-negativity, positivity, and boundedness based on the fractal–fractional sense. Hyers–Ulam stability is significant because it ensures that small deviations in the initial conditions of the system do not lead to large deviations in the solution. This implies that the proposed model is robust and reliable for predicting the behavior of virus propagation. By establishing this type of stability, we can confidently apply the model to real-world scenarios where exact initial conditions are often difficult to determine. Based on the equivalent integral of the model, a qualitative analysis is conducted by means of an iterative convergence sequence using fixed-point analysis. We then apply a numerical scheme to a case study that will allow the fractal–fractional model to be numerically described. Both analytical and simulation results appear to be in agreement. The numerical scheme not only validates the theoretical findings, but also provides a practical framework for predicting virus spread in digital networks. This approach enables researchers to assess the impact of different parameters on virus dynamics, offering insights into effective control strategies. Consequently, the model can be adapted to real-world scenarios, helping improve cybersecurity measures and mitigate the risks associated with computer virus outbreaks.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Fractional Order Mechatronics)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>An approximate numerical solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>S</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>C</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>I</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>R</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> is obtained using the fractal–fractional method in the sense of Atangana–Baleanu operators for different values, namely <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.9</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.85</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.85</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>. The parameter values used for these computations are given in <a href="#fractalfract-09-00158-t001" class="html-table">Table 1</a>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Time series of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>S</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>C</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>I</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>R</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> using fractal–fractional methods using Atangana–Baleanu operators for different values of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">

<p>An approximate numerical solution for <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>S</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>C</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>I</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>R</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> is obtained using the fractal–fractional method in the sense of Atangana–Baleanu operators for different values, namely <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.9</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.9</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.85</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.85</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>. The parameter values used for these computations are given in <a href="#fractalfract-09-00158-t001" class="html-table">Table 1</a>.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Time series of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>S</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>C</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>I</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math>, and <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mi>R</mi> <mo>(</mo> <mi>t</mi> <mo>)</mo> </mrow> </semantics></math> using fractal–fractional methods using Atangana–Baleanu operators for different values of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.98</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>, <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>0.95</mn> <mo>,</mo> <msub> <mi>σ</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msub> <mo>=</mo> <mn>1</mn> </mrow> </semantics></math>.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Multi-Focus Image Fusion Based on Fractal Dimension and Parameter Adaptive Unit-Linking Dual-Channel PCNN in Curvelet Transform Domain

by

Liangliang Li, Sensen Song, Ming Lv, Zhenhong Jia and Hongbing Ma

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 157; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030157 - 3 Mar 2025

Abstract

Multi-focus image fusion is an important method for obtaining fully focused information. In this paper, a novel multi-focus image fusion method based on fractal dimension (FD) and parameter adaptive unit-linking dual-channel pulse-coupled neural network (PAUDPCNN) in the curvelet transform (CVT) domain is proposed.

[...] Read more.

Multi-focus image fusion is an important method for obtaining fully focused information. In this paper, a novel multi-focus image fusion method based on fractal dimension (FD) and parameter adaptive unit-linking dual-channel pulse-coupled neural network (PAUDPCNN) in the curvelet transform (CVT) domain is proposed. The source images are decomposed into low-frequency and high-frequency sub-bands by CVT, respectively. The FD and PAUDPCNN models, along with consistency verification, are employed to fuse the high-frequency sub-bands, the average method is used to fuse the low-frequency sub-band, and the final fused image is generated by inverse CVT. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method shows superior performance in multi-focus image fusion on Lytro, MFFW, and MFI-WHU datasets.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Fractional Order Complex Systems: Advanced Control, Intelligent Estimation and Reinforcement Learning Image Processing Algorithms, Second Edition)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Parameter adaptive unit-linking dual-channel PCNN.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The flowchart of the proposed fusion method.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Examples of the multi-focus datasets: (<b>a</b>) Lytro, (<b>b</b>) MFFW, and (<b>c</b>) MFI-WHU.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Fusion results of the proposed algorithm with varying CVT decomposition levels on Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Level 1, (<b>d</b>) Level 2, (<b>e</b>) Level 3, (<b>f</b>) Level 4, (<b>g</b>) Level 5, (<b>h</b>) Level 6, and (<b>i</b>) Level 7.</p> Full article ">Figure 4 Cont.

<p>Fusion results of the proposed algorithm with varying CVT decomposition levels on Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Level 1, (<b>d</b>) Level 2, (<b>e</b>) Level 3, (<b>f</b>) Level 4, (<b>g</b>) Level 5, (<b>h</b>) Level 6, and (<b>i</b>) Level 7.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Results of Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>Results of Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the Lytro dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 6 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the Lytro dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Results of MFFW-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 7 Cont.

<p>Results of MFFW-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFFW dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 8 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFFW dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Results of MFI-WHU-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>Results of MFI-WHU-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFI-WHU dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 10 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFI-WHU dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Triple-series image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Source C, and (<b>d</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 11 Cont.

<p>Triple-series image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Source C, and (<b>d</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Multi-exposure image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) under-exposure image, (<b>b</b>) over-exposure image, and (<b>c</b>) proposed.</p> Full article ">

<p>Parameter adaptive unit-linking dual-channel PCNN.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>The flowchart of the proposed fusion method.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Examples of the multi-focus datasets: (<b>a</b>) Lytro, (<b>b</b>) MFFW, and (<b>c</b>) MFI-WHU.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Fusion results of the proposed algorithm with varying CVT decomposition levels on Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Level 1, (<b>d</b>) Level 2, (<b>e</b>) Level 3, (<b>f</b>) Level 4, (<b>g</b>) Level 5, (<b>h</b>) Level 6, and (<b>i</b>) Level 7.</p> Full article ">Figure 4 Cont.

<p>Fusion results of the proposed algorithm with varying CVT decomposition levels on Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Level 1, (<b>d</b>) Level 2, (<b>e</b>) Level 3, (<b>f</b>) Level 4, (<b>g</b>) Level 5, (<b>h</b>) Level 6, and (<b>i</b>) Level 7.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Results of Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 5 Cont.

<p>Results of Lytro-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the Lytro dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 6 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the Lytro dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Results of MFFW-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 7 Cont.

<p>Results of MFFW-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFFW dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 8 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFFW dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Results of MFI-WHU-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>Results of MFI-WHU-01: (<b>a</b>) GD, (<b>b</b>) MFFGAN, (<b>c</b>) LEGFF, (<b>d</b>) U2Fusion, (<b>e</b>) EBFSD, (<b>f</b>) UUDFusion, (<b>g</b>) EgeFusion, (<b>h</b>) MMAE, and (<b>i</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFI-WHU dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 10 Cont.

<p>The line chart illustrates the metrics of various data in the MFI-WHU dataset.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Triple-series image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Source C, and (<b>d</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 11 Cont.

<p>Triple-series image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) Source A, (<b>b</b>) Source B, (<b>c</b>) Source C, and (<b>d</b>) Proposed.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Multi-exposure image fusion results: (<b>a</b>) under-exposure image, (<b>b</b>) over-exposure image, and (<b>c</b>) proposed.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

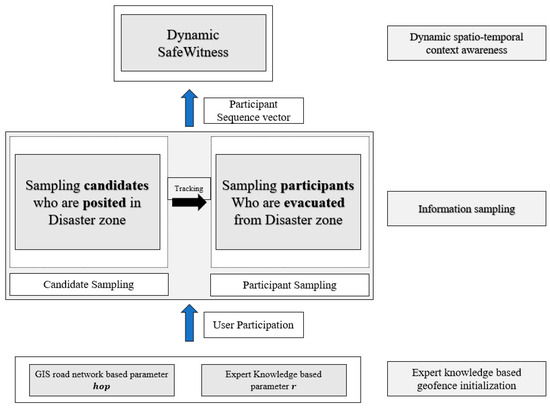

SafeWitness: Crowdsensing-Based Geofencing Approach for Dynamic Disaster Risk Detection

by

Yongmun Cho, Mincheol Shin, Ka Lok Man and Mucheol Kim

Fractal Fract. 2025, 9(3), 156; https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030156 - 3 Mar 2025

Abstract

As the frequency of disasters increases worldwide, it has become increasingly important to raise awareness of the risks and mitigate their effects through effective disaster management. Anticipating disaster risks and ensuring timely evacuations are crucial. This paper proposes SafeWitness, which dynamically captures the

[...] Read more.