The Fall of Gondolin

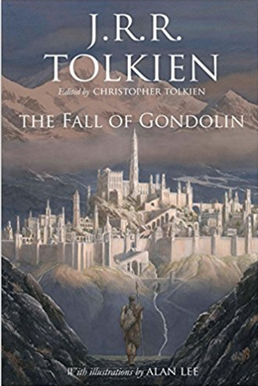

Front cover of the 2018 hardback edition, with a painting by Alan Lee | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Illustrator | Alan Lee |

| Cover artist | Alan Lee |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| Published | 2018 |

| Publisher | HarperCollins Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 304[1] |

| ISBN | 978-0008302757 |

| Preceded by | Beren and Lúthien |

J. R. R. Tolkien's The Fall of Gondolin is a 2018 book of fantasy fiction by J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by his son Christopher.[1][2] The story is one of what Tolkien called the three "Great Tales" from the First Age of Middle-earth; the other two are Beren and Lúthien and The Children of Húrin. All three stories are briefly summarised in the 1977 book The Silmarillion, and all three have now been published as stand-alone books. A version of the story also appears in The Book of Lost Tales. In the narrative, Gondolin was founded by King Turgon in the First Age. The city was carefully hidden, enduring for centuries before being betrayed and destroyed. Written in 1917, it is one of the first stories of Tolkien's legendarium.

Text

[edit]

Origins

[edit]Tolkien began writing the story that would become The Fall of Gondolin in 1917 in an army barracks on the back of a sheet of military marching music. It is one of the first stories of his Middle-earth legendarium that he wrote down on paper,[3] after his 1914 tale, inspired by the Old English manuscript Crist 1, "The Voyage of Earendel, the Evening Star".[4] While the first half of the story "appears to echo Tolkien's creative development and slow acceptance of duty in the first year of the war," the second half echoes his personal experience of battle.[5] The story was read aloud by Tolkien to the Exeter College Essay Club in the spring of 1920.[6]

Tolkien was constantly revising his First Age stories; however, the narrative he wrote in 1917, published posthumously in The Book of Lost Tales, remains the only full account of the fall of the city.[6]

Publication of versions of the story

[edit]The narrative "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin" in the 1977 book The Silmarillion was the result of the editing by his son Christopher[7] using the 1917 narrative (minus some elements all too obviously evocative of World War I warfare) and compressed versions from the different versions of the Annals and Quentas as additional sources. The later Quenta Silmarillion and the Grey Annals, the main sources for much of the published Silmarillion, both stop before the beginning of the Tuor story.

A partial later version of The Fall of Gondolin was published in the 1980 book Unfinished Tales under the title "Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin". Originally titled "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin," this narrative shows a great expansion of the earlier tale. Christopher Tolkien retitled the story before including it in Unfinished Tales, because it ends at the point of Tuor's arrival in Gondolin, and does not depict the actual Fall.[8]

There is also an unfinished poem, The Lay of the Fall of Gondolin, of which a few verses are quoted in the 1985 book The Lays of Beleriand. In 130 verses Tolkien reaches the point where dragons attack the city.

Book

[edit]Publication history

[edit]In 2018,[1] the first stand-alone version of the story was published by HarperCollins in the UK[1] and Houghton Mifflin in the US.[1] This version, illustrated by Alan Lee, was curated and edited by Christopher Tolkien,[1] J. R. R. Tolkien's son, who also edited The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and the twelve-volume The History of Middle-earth.[3]

Contents

[edit]- Prologue

- The Original Tale

- The Earliest Text

- "Turin and the Exiles of Gondolin"

- The Story Told in the Sketch of the Mythology

- The Story Told in the Quenta Noldorinwa

- The Last Version

- The Evolution of the Story

- Conclusion

The book ends with a list of names, additional notes, and a glossary.

Reception

[edit]By Tolkien scholars

[edit]Douglas Kane writes in Journal of Tolkien Research that The Fall of Gondolin was the first of Tolkien's three "Great Tales" to be written, and the last to be published, the other two being the Great Tale of Túrin Turambar (published in The Children of Húrin, 2007, edited into a continuous story) and Beren and Lúthien (2017, presented as a set of versions of the story). That left the tale which was "arguably the one in which the world of Middle-earth is most vividly presented and in which Tolkien’s philosophical themes are most profoundly expressed."[9] Kane adds that although the book collects material already published, "it still succeeds in rounding out that task", for instance by putting the "Sketch of the Mythology" in the prologue. He wonders, though, why the editor included part of the poem "The Flight of the Noldoli from Valinor" (already in The Lays of Beleriand), but omits the poem fragment "The Lay of the Fall of Gondolin" which is far more obviously relevant. Kane admires Alan Lee's illustrations, both in colour and in black and white, as providing "a perfect complement" to the final book in the "unique and remarkable" collaboration between Christopher Tolkien and his father.[9]

Jennifer Rogers, reviewing the book for Tolkien Studies, writes that it "highlights the power of the Gondolin story in its own right with minimal editorial intrusion."[10] As Tolkien's first tale and the last one to be published by his son, the book is "laden with the sense of weight such a publication brings", taking the reader back to the place where the whole Legendarium began, the story about Eärendel (later called Eärendil).[10]

In newspapers

[edit]According to Entertainment Weekly, "Patient and dedicated readers will find among the references to other books and their many footnotes and appendices a poignant sense of completion and finality to the life's pursuit of a father and son."[11] Writing for The Washington Post, writer Andrew Ervin said that "The Fall of Gondolin provides everything Tolkien's readers expect."[12] According to The Independent, "Even amid the complexities and difficulties of the book—and there are many—there is enough splendid imagery and characterful prose that readers will be carried along to the end even if they don't know where they are going."[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Helen, Daniel (10 April 2018). "The Fall of Gondolin to be published". Tolkien Society. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Helen, Daniel (30 August 2018). "The Fall of Gondolin published". Tolkien Society. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ a b "J.R.R. Tolkien's First Middle-Earth Story, The Fall of Gondolin, to Be Published". BBC. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 72.

- ^ Garth, John (2013). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 217. ISBN 978-0544263727.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1984b "The Fall of Gondolin"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin".

- ^ Tolkien 1980, "Part One: The First Age": "Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin".

- ^ a b Kane, Douglas Charles (2018). "[Review:] The Fall of Gondolin (2018) by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien". Journal of Tolkien Research. 6 (2). Article 1.

- ^ a b Rogers, Jennifer (2019). "[Review] The Fall of Gondolin by J.R.R Tolkien". Tolkien Studies. 16 (1): 170–174. doi:10.1353/tks.2019.0013. S2CID 211969055.

- ^ Lewis, Evan (25 August 2018). "The Fall of Gondolin is an indispensable examination of Tolkien's first Middle-earth story: EW review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Ervin, Andrew (28 August 2018). "J.R.R. Tolkien's latest posthumous book may actually be the last". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (31 August 2018). "JRR Tolkien, The Fall of Gondolin review: A vast and fitting last look at Middle Earth". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.