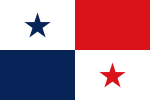

Religion in Panama

The predominant religion in Panama is Christianity, with Catholic Church being its largest denomination. Before the arrival of Spanish missionaries, the various ethnic groups residing in the territory of modern day Panama practiced a multitude of faiths.[2]

The Panamanian constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the government generally respects this right in practice.[2] The US government reported that there were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice in 2007.[2]

Overview

[edit]An official survey carried out by the government estimated in 2020 that 80.6% of the population, or 3,549,150 people, identifies itself as Roman Catholic, and 10.4 percent as evangelical Protestant, or 1,009,740.[1] The Jehovah's Witnesses were the third largest congregation comprising the 1.4% of the population, followed by the Adventist Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with the 0.6%. There is a Buddhist (0.4% or 18,560) and a Jewish community (0.1% or 5,240) in the country. The Baháʼí Faith community of Panama is estimated at 2.00% of the national population, or about 60,000[3] including about 10% of the Guaymí population;[4] the Baháʼís maintain one of the world's eight Baháʼí Houses of Worship in Panama.[2]

Distribution in 2007

[edit]

Catholics are found throughout the country and at all levels of society.[2] Evangelical Christians also are dispersed geographically and are becoming more prominent in society.[2] The mainstream Protestant denominations, which include Southern Baptist Convention and other Baptist congregations, United Methodist, Methodist Church of the Caribbean and the Americas, and Lutheran, derive their membership from the Antillean black and the expatriate communities, both of which are concentrated in Panamá and Colón Provinces.[2] The Jewish community is centered largely in Panama City.[2] Muslims live primarily in Panama City and Colon, with smaller concentrations in David and other provincial cities.[2] The vast majority of Muslims are of Lebanese, Palestinian, or Indian descent.[2]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) claim more than 40,000 members.[6] Smaller religious groups include Buddhists with between 15,000 and 20,000 members, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Episcopalians with between 7,000 and 10,000 members, Muslim communities with approximately 10,000 members each, Hindus, and other Christians.[2] Indigenous religions include Ibeorgun (among Kuna) and Mamatata (among Ngobe).[2] There is also a small number of Rastafarians.[2]

Judaism in Panama

[edit]Colonial Period

[edit]The presence of anusim or crypto-Jews has been documented since the early migrations of Spaniards and Portuguese to the territory. There is no evidence of an openly practicing Jewish community due to the legal limitations of the time. However, it is relevant to mention an attempt to establish a synagogue led by the Portuguese Sebastian Rodríguez, who was arrested on charges of practicing Judaism. His accomplices in this matter included Antonio de Ávila, González de Silva, Domingo de Almeyda, and a Mercedarian friar who also practiced Judaism. Four doctors certified the presence of the circumcision mark in Rodríguez's case.[7]

Union to Colombia Period

[edit]When the Isthmus joined Simón Bolívar's Federation project, a new Hebrew migration took place, revitalizing the Mosaic faith on isthmian soil. These early Jewish immigrants arrived under a new initial policy that promoted religious freedom in the newly independent territories. They played a crucial role as intermediaries and translators, bridging the gap between the local population and foreigners arriving or passing through the region, thanks to their proficiency in languages such as German, Spanish, French, English, Dutch, and Papiamento.

Jews, both Sephardic (Judeo-Spanish) and Ashkenazi (Judeo-German), began to arrive in significant numbers in Panama in the mid-19th century, drawn by economic opportunities such as the construction of the transoceanic railroad and the California Gold Rush. This migration marked an important chapter in the history of the Jewish community in Panama.

Republican Period

[edit]The Republic of Panama, in its current form, would have experienced a very different reality without the notable contributions of the Panamanian Jewish community. Their role in the country's independence movement in 1903 was of crucial importance and prevented the failure of the separatist movement. Distinguished members of the Kol Shearith Israel Congregation, such as Isaac Brandon, M.D. Cardoze, M.A. De León, Joshua Lindo, Morris Lindo, Joshua Piza, and Isaac L. Toledano, provided essential financial support to the Revolutionary Junta when Philippe Jean Bunau-Varilla's promises of funds did not materialize. Without their contribution, the lives of the leaders of Panama's separation from Colombia could have been in jeopardy.[8]

Following this period, there were other waves of Jewish immigration to Panama. During World War I, individuals from the disintegrating Ottoman Empire arrived in the country. After World War II, there was immigration from Europe, and Jews from Arab countries arrived due to the 1948 exodus. More recently, Jewish immigrants from South American nations facing economic crises have joined the Panamanian Jewish community. These groups have contributed to the diversity of the Jewish population in present-day Panama.

The epicenter of Jewish life is in Panama City, although historically, small Jewish communities were established in other cities such as Colon, David, Chitré, Las Tablas (since the late 17th century), La Chorrera, Santiago de Veraguas, and Bocas del Toro. As families moved to the capital in search of education for their children and for economic reasons, these communities gradually dissolved.

Despite their relatively small demographic size compared to the total population of the country (approximately four million inhabitants), the Jewish community numbers between 15,000 to 17,000 people. Currently, the vibrant Jewish community is concentrated in Panama City and is fully integrated into Panamanian society. Unlike in other countries, Panamanian Jews actively participate in trade, government, civic functions, and diplomacy. With the exception of Israel, Panama is the only country in the world to have had two Jewish presidents in the 20th century:

In the 1960s, Max Delvalle first served as vice president and then as president of the Republic. Delvalle is known for his inaugural speech in which he stated, "Today there are two Jewish presidents in the world, the president of the State of Israel and myself." Later, his nephew, Eric Arturo Delvalle, assumed the presidency of the Republic between 1985 and 1988. Both were members of the Kol Shearit Israel synagogue and were involved in Jewish life in Panama.

Historical Trends

[edit]- Sources: Based on Pew Center Research (including historical percentages of Catholicism),[9] by ends-1900 there were 26,000 U.S American[10] (more than half being Protestants) stablished for the Canal construction making the 9% in a total population of 290,000 (1911 Census)

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Panama |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Freedom of religion

[edit]In 2023, the country was scored 4 out of 4 for religious freedom.[11]

See also

[edit]- Christianity in Panama

- Baháʼí Faith in Panama

- Islam in Panama

- Hinduism in Panama

- History of the Jews in Panama

- Freedom of religion in Panama

- Sikhism in Panama

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Hogares, Panama 2020" (PDF). Ministerio Público de la República de Panamá. December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Panama. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Panama". WCC > Member churches > Regions > Latin America > Panama. World Council of Churches. 2006-01-01. Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (October–December 1994). "In Panama, some Guaymis blaze a new path". One Country. 1994 (October–December).

- ^ Katzman, Patricia. Panama. Hunter Publishing (2005), p106. ISBN 1-58843-529-6.

- ^ Panama Archived 2008-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. LDS Newsroom. Retrieved 2008-12-13

- ^ Byrzdett, Elyjah (2023). Crypto-Jews in the Isthmus of Panama: 16th-17th centuries (1 ed.). ISBN 979-8397623285.

- ^ Byrzdett, Elyjah. PANAMÁ JUDÍA: Breve historia de la inmigración hebrea al Istmo (in Spanish). ISBN 979-8831870954.

- ^ "Religion in Latin America, Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region". Pew Research Center. 13 November 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ "Looking for an Ancestor in the Panama Canal Zone, 1904-1914 | National Archives". 15 August 2016.

- ^ Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-08

External links

[edit]- Religious radiostations in Panama List with over 20 online broadcasting Panamanian radiostations

- Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Hogares, Panama 2015 via WaybackMachine