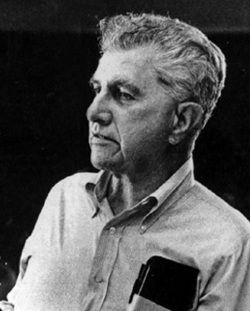

Merton Miller

Merton Miller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 16, 1923 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | June 3, 2000 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Harvard University Johns Hopkins University |

| Academic career | |

| Field | Economics |

| Institution | Carnegie Mellon University University of Chicago London School of Economics |

| School or tradition | Chicago School of Economics |

| Doctoral advisor | Fritz Machlup |

| Doctoral students | Eugene Fama William Poole |

| Contributions | Modigliani–Miller theorem |

| Awards | Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (1990) |

| Information at IDEAS / RePEc | |

Merton Howard Miller (May 16, 1923 – June 3, 2000) was an American economist, and the co-author of the Modigliani–Miller theorem (1958), which proposed the irrelevance of debt-equity structure. He shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990, along with Harry Markowitz and William F. Sharpe. Miller spent most of his academic career at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Miller was born in Boston, Massachusetts to Jewish parents Sylvia and Joel Miller,[1][2] a housewife and attorney. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate student. He worked during World War II as an economist in the division of tax research of the Treasury Department, and received a Ph.D. in economics from Johns Hopkins University, 1952. His first academic appointment after receiving his doctorate was Visiting Assistant Lecturer at the London School of Economics.

Career

[edit]In 1958, at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), he collaborated with his colleague Franco Modigliani on the paper The Cost of Capital, Corporate Finance and the Theory of Investment. This paper urged a fundamental objection to the traditional view of corporate finance, according to which a corporation can reduce its cost of capital by finding the right debt-to-equity ratio. According to the Modigliani–Miller theorem, on the other hand, there is no right ratio, so corporate managers should seek to minimize tax liability and maximize corporate net wealth, letting the debt ratio chips fall where they will.

The way in which they arrived at this conclusion made use of the "no arbitrage" argument, i.e. the premise that any state of affairs that will allow traders of any market instrument to create a riskless money machine will almost immediately disappear. They set the pattern for many arguments based on that premise in subsequent years.

Miller wrote or co-authored eight books. He became a fellow of the Econometric Society in 1975 and was president of the American Finance Association in 1976. He was on the faculty of the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business from 1961 until his retirement in 1993, although he continued teaching at the school for several more years.

His works formed the basis of the "Modigliani-Miller Financial Theory".

He served as a public director on the Chicago Board of Trade 1983–85 and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange from 1990 until his death in Chicago on June 3, 2000. In 1993, Miller waded into the controversy surrounding $2 billion in trading losses by what was characterized as a rogue futures trader at a subsidiary of Metallgesellschaft, arguing in the Wall Street Journal that management of the subsidiary was to blame for panicking and liquidating the position too early.[3] In 1995, Miller was engaged by Nasdaq to rebut allegations of price fixing.[4]

Personal life

[edit]Miller was married to Eleanor Miller, who died in 1969. He was survived by his second wife, Katherine Miller, and by three children from his first marriage: Pamela (1952), Margot (1955), and Louise (1958), and two grandsons.[5]

Bibliography

[edit]- Merton H. Miller (1991). Merton Miller on Derivatives. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-18340-7.

- Merton H. Miller (1991). Financial Innovations and Market Volatility. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-55786-252-4.

- Merton, Miller H.; Charles W. Upton (1986). Macroeconomics: A Neoclassical Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52623-2.

- Kessel, Reuben A.; R. H. Coase; Merton H. Miller (1980). Essays in Applied Price Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-43200-9.

- Fama, Eugene F.; Merton H. Miller (1972). The Theory of Finance. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 0-03-086732-0.

- Merton H. Miller (1997). "The Private Interest & the Public Interest". The Green Bag.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Merton H. Miller". The Notable Names Database. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Encyclopedia of American Jewish history. Norwood, Stephen H. (Stephen Harlan), 1951-, Pollack, Eunice G. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. 2008. ISBN 978-1851096381. OCLC 174966865.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Markham, Jerry W. (2006). A Financial History of Modern U.S. Corporate Scandals: From Enron to Reform. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. p. 78. ISBN 0-7656-1583-5. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Nasdaq Hires Nobel Laureate to Help Fend Off Allegations". Los Angeles Times. Bloomberg Business News. March 14, 1995. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Louis Uchitelle (2000). "Merton H. Miller, 77, Dies; Economist Who Won Nobel," New York Times, June 5.[1]

External links

[edit]- "Merton H. Miller (1923–2000)". The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty (2nd ed.). Liberty Fund. 2008.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Merton H. Miller on Nobelprize.org including the Prize Lecture December 7, 1990 Leverage

- Guide to the Merton H. Miller Papers 1941-2002 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- 1923 births

- 2000 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Economics

- American Nobel laureates

- American financial economists

- American business theorists

- Harvard University alumni

- Johns Hopkins University alumni

- University of Chicago faculty

- Carnegie Mellon University faculty

- Corporate finance theorists

- Jewish American economists

- 20th-century American economists

- Fellows of the Econometric Society

- Distinguished fellows of the American Economic Association

- Presidents of the American Finance Association