Jabba the Hutt

| Jabba the Hutt | |

|---|---|

| Star Wars character | |

Jabba the Hutt[a] | |

| First appearance | Return of the Jedi (1983) |

| Created by | George Lucas |

| Voiced by |

|

| Performed by | David Barclay Toby Philpott Mike Edmonds |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Hutt[1] |

| Gender | Male[2] |

| Occupation | Crime lord[2] |

| Affiliation | Grand Hutt Council[3] Crymorah Syndicate[3] |

| Family | |

| Children | Rotta (son)[12] |

| Homeworld | Nal Hutta[13] |

Jabba the Hutt (/dʒɑːˈbə/) is a fictional character in the Star Wars franchise. He is a large, slug-like crime lord of the Hutt species. Jabba first appeared in the 1983 film Return of the Jedi, in which he is portrayed by a one-ton puppet operated by several puppeteers. In 1997, he appeared in the Special Edition of the original Star Wars film, which had been retitled Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope. Jabba made his third film appearance in the 1999 prequel film The Phantom Menace. He is voiced by Larry Ward in Return of the Jedi and by Scott Schumann in A New Hope and The Phantom Menace.

Jabba lives in a palace on the desert planet Tatooine. He places a bounty on the smuggler Han Solo, and sends bounty hunters to capture him. After Darth Vader freezes Solo in carbonite, the bounty hunter Boba Fett delivers the frozen Solo to Jabba, who puts him on display in his palace. A group of Solo's friends attempt to rescue him, but Jabba captures them; he enslaves Princess Leia and decrees that Luke Skywalker, Chewbacca, and Solo will be fed to a Sarlacc. Luke orchestrates an escape, and during the chaos Leia strangles Jabba to death.

Creation and portrayal

[edit]Star Wars

[edit]George Lucas wrote and directed Star Wars, which was released in 1977. The script included a scene in which the smuggler Han Solo negotiates with Jabba about a payment he owes him. The scene was meant to give Solo the motivation to transport dangerous passengers for a high fare. It was also meant to explain why Solo was imprisoned in the following film, The Empire Strikes Back.[14]

In a 1985 interview, Lucas said he originally imagined Jabba as a furry creature that resembled a Wookiee. By the time he completed the Star Wars screenplay, Jabba had evolved into a fat, slug-like creature with a gaping mouth and eyes on extended feelers. When filming Jabba's scene, Declan Mulholland served as a stand-in for the crime lord. Lucas planned to replace Mulholland in post-production with an animated creature.[15] Lucas ultimately cut the scene due to budget and time constraints, and because he felt it did not contribute to the film's plot.[16] According to Paul Blake, who plays the bounty hunter Greedo, his character's scene was added to Star Wars after Lucas decided to cut the scene with Jabba.[17]

Return of the Jedi

[edit]Although Jabba did not appear in Star Wars, he is mentioned in the film and its first sequel, The Empire Strikes Back. He finally appeared in the second sequel, Return of the Jedi (1983). His appearance is similar to the way he was described in the Star Wars script: He is a large, slug-like creature with a wide mouth. Before Lucas settled on this design, he considered other versions of the character. At various points, Jabba resembled an ape, a worm and a snail. One design made Jabba appear too human—almost like a Fu Manchu character.[18][19] Nilo Rodis-Jamero, the costume designer for Return of the Jedi, said he had envisioned Jabba as a refined, intelligent man resembling Orson Welles.[18]

After an initial design was approved, further design work was done by Phil Tippett, the film's visual effects artist. He based Jabba's body structure and reproductive system on the anatomy of annelid worms. He modeled Jabba's head on that of a snake, complete with bulbous, slit-pupilled eyes and a mouth that opens wide enough to swallow large prey. He gave Jabba's skin a moist, amphibian quality.[20][21]

The next task was to create the Jabba puppet, a process which took three months and cost $500,000. Stuart Freeborn and the Industrial Light & Magic Creature Shop designed the one-ton puppet, while John Coppinger sculpted its latex, clay, and foam pieces. The puppet had its own makeup artist and required three puppeteers to operate, making it one of the largest puppets ever used in a film.[19] The puppeteers included David Barclay, Toby Philpott, and Mike Edmonds, who were members of Jim Henson's Muppet group. Barclay operated the right arm and mouth, while Philpott controlled the left arm, head, and tongue. Edmonds was responsible for the movement of Jabba's tail. The character's eyes and face were operated by radio control.[15][19][22] Lucas complained about the difficulty of moving the massive puppet around the set. He was also disappointed by its appearance, later stating that Jabba would have been a computer-generated character if the required technology had existed at the time.[22]

Jabba's voice was provided by Larry Ward, who was uncredited in the film.[23] A heavy, booming quality was given to Ward's voice by pitching it an octave lower than normal and processing it through a subharmonic generator.[24] A soundtrack of wet, slimy sound effects was recorded to accompany the movement of Jabba's limbs and mouth.[25] The film's composer, John Williams, arranged a musical theme for Jabba that is played on a tuba.[26] Williams later turned the theme into a symphonic piece which he performed with the Boston Pops Orchestra. The musicologist Gerald Sloan said the Jabba theme "blends the monstrous and the lyrical".[27] According to the film historian Laurent Bouzereau, Jabba's strangulation by Leia was inspired by a scene from The Godfather (1972), in which the obese character Luca Brasi is garroted by an assassin.[28]

A New Hope – 1997 Special Edition

[edit]A New Hope.

In 1997, the Special Edition of Star Wars was released, now titled Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope. Lucas revisited the Jabba scene he had filmed (and ultimately cut) and completed it for the Special Edition, replacing the stand-in actor Mulholland with a computer-generated version of Jabba. He also replaced the English dialogue with Huttese, a fictional language created by Ben Burtt, the film's sound designer. The scene consisted of five shots and took over a year to complete. Joseph Letteri, the visual effects supervisor for the Special Edition, said his goal was to make Jabba look as realistic as a flesh-and-blood character.[29][30] The scene was refined for the 2004 DVD release, with improvements to Jabba's appearance made possible by advancements in CGI.[31][better source needed]

At one point during the scene, Ford walks behind Mulholland. This became a problem when adding the CG Jabba, since his tail would be in Solo's path. The solution was to have Solo step on Jabba's tail, causing him to yelp in pain. In the 2004 DVD release, Jabba reacts more strongly, winding up as if to punch Solo. In this version, shadows cast by Solo were added to Jabba's body to make the CGI more convincing.[22] According to Lucas, some viewers were disappointed with the digital Jabba's appearance, complaining that the character did not look realistic. Lucas dismissed this criticism, claiming that regardless of whether a character is portrayed by a puppet or CGI, it will always look unrealistic to some degree.[22]

Characterization

[edit]Jabba has been described as an exemplar of lust, greed, and gluttony.[32] His criminal operations include slavery, gunrunning, spice-smuggling and extortion.[33] He amuses himself by torturing, humiliating and killing both his enemies and his own subordinates.[34] He surrounds himself with scantily-clad slave girls of various species, often chained to his dais.[35] Jabba's appetite is insatiable, and he sometimes threatens to eat his underlings.[36][37]

In Return of the Jedi, Solo calls Jabba a "slimy piece of worm-ridden filth". The authors Martha and Tom Veitch called his body a "miasmic mass" that seems to release "a greasy discharge, sending fresh waves of rotten stench" into the air.[38] Arthur Knight of The Hollywood Reporter described Jabba as a "truly frightening ... walrus-shaped grotesque."[39] The science fiction writer Jeanne Cavelos wrote that he deserves an award for "most disgusting alien", while the film critic Roger Ebert described him as loathsome and evil.[40][41]

Appearances

[edit]Films

[edit]Although he was mentioned in previous films, Jabba was first seen in Return of the Jedi (1983), the third film of the original trilogy. The beginning of the film features the attempts of Princess Leia, Chewbacca and Luke Skywalker to rescue Han Solo, who was imprisoned in carbonite in The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Jabba has put the hibernating Solo on display in his throne room as a decoration. Leia is able to free Han from the carbonite, but she is caught and enslaved by Jabba, who forces her to wear a metal bikini. Luke arrives to bargain for Solo's life, but Jabba rejects his offer and attempts to feed him to a rancor. After Luke kills the monster, Jabba decrees that he, Solo and Chewbacca will be fed to a Sarlacc, a deadly ground-dwelling beast. Luke orchestrates an escape with the help of R2-D2, and defeats Jabba's thugs. During the chaos, Leia strangles Jabba to death with the chain used to enslave her. As Luke and his friends depart, Jabba's sail barge explodes.

Jabba appears in the Special Edition of Star Wars, which was released in 1997. He is voiced by Scott Schumann. In the film, Jabba meets with Solo, who pledges to pay Jabba for lost cargo. Jabba threatens to place a large bounty on him if he does not follow through. Jabba also appears briefly in the 1999 prequel film The Phantom Menace, again voiced by Schumann.[42] He launches a podrace at Mos Espa, then falls asleep and misses the conclusion of the race.[43]

The Clone Wars

[edit]Jabba's son Rotta is captured by Separatists in the animated film The Clone Wars (2008). It is later revealed that Ziro, Jabba's uncle, took part in the kidnapping as part of his plan to take control of the Hutt Clan. The Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker and his apprentice Ahsoka Tano return Rotta to Jabba in exchange for the safe passage of Republic ships through his territory. Padmé Amidala exposes Ziro's crimes to Jabba; outraged by his uncle's betrayal, he vows to ensure that Ziro will be severely punished.[44]

Jabba appears in several episodes of The Clone Wars series (2008–2014; 2020). In "Sphere of Influence", he is confronted by Chairman Papanoida, whose daughters were kidnapped by Greedo. Jabba allows a sample of Greedo's blood to be taken to prove he is the kidnapper.[45][46] In "Evil Plans", Jabba hires the bounty hunter Cad Bane to bring him plans for the Galactic Senate building. When Bane returns with the plans, Jabba and the Hutt Council send him to free Ziro from prison.[47][48] Jabba makes a brief appearance in "Hunt for Ziro", in which he laughs at his uncle's death at the hands of Sy Snootles, and pays her for delivering Ziro's holo-diary.[44][49] In "Eminence", Jabba and the Hutt Council are approached by the Shadow Collective leaders Darth Maul, Savage Opress and Pre Vizsla. Jabba is not willing to ally with them, and sends the bounty hunters Embo, Dengar, Sugi and Latts Razzi to capture them. After a battle, the Shadow Collective confronts Jabba at his palace on Tatooine, where he finally agrees to an alliance.[50][51]

Other

[edit]Jabba is voiced by Ed Asner in the radio dramatizations of the original trilogy.[52]

Star Wars Legends

[edit]Following the acquisition of Lucasfilm by The Walt Disney Company in 2012, most of the licensed Star Wars novels and comics produced between 1977 and 2014 were rebranded as Star Wars Legends and declared non-canon to the franchise. The Legends works comprise a separate narrative universe.[j]

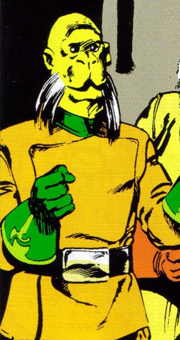

The first appearances of Jabba in any visual capacity were in Marvel Comics' adaptation of A New Hope, which includes Six Against the Galaxy (1977), What Ever Happened to Jabba the Hut? (1979)[k] and In Mortal Combat (1980). In these comics, Jabba appears as a tall humanoid with a walrus-like face, a topknot, and a brightly-colored uniform.[57] He was based on a character later named Mosep Binneed, who appears briefly in the Mos Eisley Cantina scene in Star Wars.[15][58][59]

While awaiting the sequel to Star Wars, Marvel kept the monthly comic going with its own stories, one of which depicts Jabba tracking down Solo and Chewbacca to an old hideaway they use for smuggling. Circumstances force Jabba to lift the bounty on Solo and Chewbacca, which enables them to return to Tatooine for an adventure with Luke. In another story, Solo kills the space pirate Crimson Jack and busts up his operation, which Jabba bankrolled. Jabba then renews the bounty on Solo.[58][59]

The 1977 novelization of Lucas's Star Wars script describes Jabba as a "great mobile tub of muscle and suet topped by a shaggy scarred skull", but gives no further detail about his appearance or species.[60]

Zorba the Hutt's Revenge (1992), a young-adult novel by Paul and Hollace Davids, identifies Jabba's father as another powerful crime lord named Zorba and reveals that Jabba was born 596 years before the events of A New Hope, making him around 600 years old at the time of his death in Return of the Jedi.[61] Four comics exploring Jabba's backstory were written by Jim Woodring and released by Dark Horse Comics between 1995–1996; these were published collectively as Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal in 1998.[62][63] Ann C. Crispin's novel The Hutt Gambit (1997) explains how Jabba and Solo become business associates and depicts the events that lead to a bounty being placed on Han's head.[64]

Tales from Jabba's Palace (1996), a collection of short stories edited by Kevin J. Anderson, pieces together the lives of Jabba's various minions and their relationship to him during the last days of his life. These stories reveal that many of Jabba's servants are resentful towards him and want to assassinate him. After Jabba is killed in Return of the Jedi, his surviving courtiers join forces with his rivals on Tatooine. At the same time, Jabba's family on the Hutt homeworld Nal Hutta make claims to his palace, fortune, and criminal empire.[13] Timothy Zahn's novel Heir to the Empire (1991) reveals that a smuggler named Talon Karrde eventually replaces Jabba as the "big fish in the pond" and moves the headquarters of his criminal empire off of Tatooine.[65]

Reception

[edit]The Telegraph called Jabba one of the most memorable creatures in the Star Wars franchise.[66] Business Insider's Travis Clark said, "Like Stormtroopers or Darth Vader, some villains just come to mind when you think of Star Wars. Jabba is another one of them."[67] Rolling Stone said that Jabba is "without a doubt the finest Star Wars portrait of the id" and that one has to "admire his dedication of being his true, absolutely horrendous self".[68] The Denver Post applauded the special effects team on Return of the Jedi for making Jabba look like a "horrid creature".[69]

Several commentators have derided the computer-generated versions of Jabba and other Hutts. Phil Owen of TheWrap said the digital Jabba in the 1997 release of A New Hope looked "incredibly horrible", while Matt Goldberg of Collider called it "awful".[70][71] After the appearance of the Hutt Twins in the series The Book of Boba Fett, Matt Singer of ScreenCrush wrote that no Hutt should ever be CG, as it does not appear realistic.[72]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Return of the Jedi (1983)

- ^ Return of the Jedi

- ^ Star Wars Special Edition

The Phantom Menace - ^ Return of the Jedi radio drama

- ^ The Phantom Menace (video game)

Star Wars: Demolition

Star Wars: Galactic Battlegrounds

Star Wars: Bounty Hunter - ^ Star Wars: The Force Unleashed

- ^ Lego Star Wars: The Yoda Chronicles

- ^ The Clone Wars film and television series

Disney Infinity 3.0

Lego Star Wars: The Freemaker Adventures

Lego Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga - ^ Jabba the Hutt's family members in the Star Wars Legends narrative universe include his father Zorba,[8] his uncle Jiliac,[9] his uncle Pazda,[10] and his nephew Grubba.[11]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[53][54][55][56] - ^ "Hutt" was originally spelled "Hut".

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Hutt". StarWars.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b "Jabba the Hutt". StarWars.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Beecroft & Hidalgo 2016, p. 105.

- ^ a b Morrison, Matt (January 5, 2022). "The Twins & Hutt Clans Explained: How They Connect To Jabba". ScreenRant. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b "Ziro the Hutt". StarWars.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Hidalgo & Sansweet 2008a, p. 353.

- ^ Sumerak, Marc (November 6, 2018). Star Wars: Droidography. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-286219-8.

- ^ Hidalgo & Sansweet 2008b, p. 130.

- ^ Hidalgo & Sansweet 2008b, p. 163.

- ^ Hidalgo & Sansweet 2008c, p. 15.

- ^ Hidalgo & Sansweet 2008a, p. 372.

- ^ "Rotta the Huttlet". StarWars.com. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ a b Anderson, Kevin J., ed. (1996). Tales from Jabba's Palace. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-56815-9.

- ^ Lucas, George (1997). Interview on Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope, Special Edition (VHS). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b c "Jabba the Hutt, Behind the Scenes". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Lucas, George (2004) Commentary track on Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope, Special Edition (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Carbone, Gina (November 17, 2019). "Greedo Actor Is Confused By 'Maclunkey,' And Star Wars In General". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Bouzereau, Laurent (1997). Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. New York: Del Rey. p. 239. ISBN 0-345-40981-7.

- ^ a b c From Star Wars to Jedi: The Making of a Saga (1992). CBS Fox Video (VHS).

- ^ "Biography of Phil Tippett". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Sansweet, Stephen J. (1998). "Hutt". Star Wars Encyclopedia. New York: Del Rey. p. 134. ISBN 0-345-40227-8.

- ^ a b c d Lucas, George (2004). Commentary track on Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi, Special Edition (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "Jabba the Hutt Voice". Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Holman, Tomlinson (2002). Sound for Film and Television. Burlington, Massachusetts: Focal Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-240-80453-8.

- ^ Burtt, Ben (2004). Commentary track on Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi, Special Edition (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "Review of Return of the Jedi soundtrack". Filmtracks.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Sloan, Gerald (June 27, 2000). "Evening The Score: UA Professor Explores Tuba Music In Film". Daily Digest. University of Arkansas. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Bourezeau, Laurent (1997). Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. Ballantine Books. p. 259. ISBN 978-0345409812.

- ^ Letteri, Joseph (1997). Interview on Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope, Special Edition (VHS). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "A New Hope: Special Edition – What has changed?". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Malcolm; Woodward, Tom. "Star Wars: The Changes — Part One". DVDActive. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010.

- ^ Pomerance, Murray (2004). Schneider, Steven Jay (ed.). "Hitchcock and the Dramaturgy of Screen Violence". New Hollywood Violence. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press: 47. ISBN 0-7190-6723-5.

- ^ "Character: Jabba the Hutt". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Kahn, James (May 12, 1983). Return of the Jedi: Star Wars: Episode VI. Random House Worlds. ISBN 978-0-345-30767-5.

- ^ Tyers, Kathy (1996). "A Time to Mourn, A Time to Dance: Oola's Tale". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from Jabba's Palace. p. 80.

- ^ Windham, Ryder (1996). "This Crumb for Hire". A Decade of Dark Horse #2. Dark Horse Comics.

- ^ Friesner, Esther M. (1996). "That's Entertainment: The Tale of Salacious Crumb". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from Jabba's Palace. pp. 60–79.

- ^ Veitch, Tom; Veitch, Martha (1996). "A Hunter's Fate: Greedo's Tale". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina. New York City: Bantam Spectra. pp. 49–53. ISBN 0-553-56468-4.

- ^ Knight, Arthur (November 28, 2014). "'Star Wars: Return of the Jedi': THR's 1983 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Cavelos, Jeanne (1999). Just Because It Goes 'Ho Ho Ho' Doesn't Mean It's Santa: The Science of Star Wars: An Astrophysicist's Independent Examination of Space Travel, Aliens, Planets, and Robots as Portrayed in the Star Wars Films and Books. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-312-20958-4.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (May 25, 1983). "Return of the Jedi review". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago: Sun-Times Media Group. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Holman, Tomlinson (June 20, 2014). Surround Sound: Up and Running – 2nd Edition. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136115899. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ "Mos Espa Grand Arena". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Roy, Jennifer (December 20, 2022). "Will Star Wars: The Book of Boba Fett Feature Jabba the Hutt's Family?". ComicBook.com. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Blauvelt, Christian (October 1, 2010). "'Star Wars: The Clone Wars' recap: Greedo shot first!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ McEwan, Cameron (October 4, 2010). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars season 3 episode 4 review: Sphere Of Influence". Den of Geek. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ McEwan, Cameron (November 15, 2010). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars season 3 episode 8 review: Evil Plans". Den of Geek. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (May 4, 2012). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars - "Evil Plans" Review". IGN. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (May 4, 2012). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars - "Hunt for Ziro" Review". IGN. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "SHADOWS OF THE SITH". StarWars.com. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (January 19, 2013). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars - "Eminence" Review". IGN. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Ryan, Mike (April 2, 2015). "That Time John Lithgow Played Yoda And Ed Asner Played Jabba The Hutt For A 'Star Wars' Radio Broadcast". Uproxx. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ McMilian, Graeme (April 25, 2014). "Lucasfilm Unveils New Plans for Star Wars Expanded Universe". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "The Legendary Star Wars Expanded Universe Turns a New Page". StarWars.com. April 25, 2014. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "Disney and Random House announce relaunch of Star Wars Adult Fiction line". StarWars.com. April 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ Dinsdale, Ryan (May 4, 2023). "The Star Wars Canon: The Definitive Guide". IGN. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Mcguire, Liam (October 6, 2021). "Star Wars: Marvel Accidentally Made Jabba The Hutt A Different Creature". Screen Rant. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Roy Thomas (w). "Six Against the Galaxy" Marvel Star Wars, no. 2 (August 1977). Marvel.

- ^ a b Archie Goodwin (w). "In Mortal Combat" Marvel Star Wars, no. 37 (July 1980). Marvel..

- ^ Lucas, George (1977). Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker (paperback ed.). New York: Del Rey. p. 107. ISBN 0-345-26079-1.

- ^ Davids, Paul; Davids, Hollace (1992). Zorba the Hutt's Revenge. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-15889-9.

- ^ Jim Woodring (w). Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal (1998). Dark Horse Comics, ISBN 1-56971-310-3.

- ^ Von Busack, Richard (August 6, 1998). "Jabba the Hutt slimes his way through a new graphic novel". metroactive.com. Metroactive Books. Archived from the original on December 31, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Crispin, Anne C. (1997). The Hutt Gambit. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-57416-7.

- ^ Zahn, Timothy (1991). Heir to the Empire. New York City: Bantam Spectra. p. 27. ISBN 0-553-29612-4.

- ^ "Jabba the Hutt: 67 Star Wars characters, ranked from worst to best". The Telegraph. May 4, 2021. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022.

- ^ Clark, Travis (May 23, 2018). "The 30 most important 'Star Wars' movie villains, ranked from worst to best". Business Insider. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan; Fischer, Russ; Tobias, Scott; Ehrlich, David; Murray, Noel; Grierson, Tim; Collins, Sean (May 4, 2020). "50 Best 'Star Wars' Characters of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ ""Return of the Jedi" original Star Wars movie review – 1983". The Denver Post. May 25, 1983. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Owen, Phil (August 23, 2021). "13 Movies That Had Absolutely Aweful CGI (Photos)". TheWrap. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (February 10, 2012). "Editorial: It's Time to Make Peace with STAR WARS". Collider. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Singer, Matt (January 6, 2022). "'Star Wars' Hutts Should Never, Ever Be CGI". ScreenCrush. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

Works cited

[edit]- Beecroft, Simon; Hidalgo, Pablo (2016). Star Wars Character Encyclopedia: Updated and Expanded (eBook ed.). New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 9781465454966. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- Hidalgo, Pablo; Sansweet, Stephen (2008a). The Complete Star Wars Encyclopedia. Vol. I (First ed.). New York: Del Rey. ISBN 9780345477637.

- Hidalgo, Pablo; Sansweet, Stephen (2008b). The Complete Star Wars Encyclopedia. Vol. II (First ed.). New York: Del Rey. ISBN 9780345477637.

- Hidalgo, Pablo; Sansweet, Stephen (2008c). The Complete Star Wars Encyclopedia. Vol. III (First ed.). New York: Del Rey. ISBN 9780345477637.

Further reading

[edit]- Deerwester, Jayme (August 20, 2016). "Carrie Fisher: Trump should play Jabba the Hutt". USA Today. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- Failla, Zak (April 3, 2021). "First Accuser Compares Cuomo Embrace To Star Wars Character". The Daily Voice. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- Kuiper, Koenraad (Spring 1988). "Star Wars: An Imperial Myth". Journal of Popular Culture. 21 (4): 78. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1988.78417.x.

- Peckham, Matt (January 24, 2013). "Is This LEGO Star Wars Toy Racist?". Time. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- Stark, Sarah (March 1, 2022). "It's Time to Abolish the Fat Villain Trope". Inverse.com. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Jabba the Hutt in the StarWars.com Databank

- Characters created by George Lucas

- Film characters introduced in 1983

- Fictional arms dealers

- Fictional crime bosses

- Fictional criminals in films

- Fictional criminals in television

- Fictional dictators

- Fictional gangsters

- Fictional gamblers

- Fictional gastropods

- Fictional murderers

- Fictional slave owners

- Fictional kidnappers

- Film supervillains

- Extraterrestrial supervillains

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in television

- Return of the Jedi

- Star Wars animated characters

- Star Wars Skywalker Saga characters

- Star Wars: The Clone Wars characters

- Male film villains

- Fictional mass murderers