Federalist No. 70

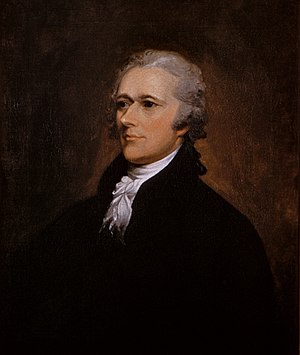

Alexander Hamilton, author of Federalist No. 70 | |

| Author | Alexander Hamilton |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Executive Department Further Considered |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | The New York Packet |

Publication date | March 15, 1788 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Newspaper |

| Preceded by | Federalist No. 69 |

| Followed by | Federalist No. 71 |

Federalist No. 70, titled "The Executive Department Further Considered", is an essay written by Alexander Hamilton arguing for a single, robust executive provided for in the United States Constitution.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] It was originally published on March 15, 1788, in The New York Packet under the pseudonym Publius as part of The Federalist Papers and as the fourth in Hamilton's series of eleven essays discussing executive power.[10]

Hamilton argues that unity in the executive branch is a main ingredient for both energy and safety.[2][7][8] Energy arises from the proceedings of a single person, characterized by, "decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch," while safety arises from the unitary executive's unconcealed accountability to the people.[4][5][7][8][11]

Historical and philosophical influences

[edit]

Before ratifying the Constitution in 1787, the thirteen states were bound by the Articles of Confederation, which authorized the Congress of the Confederation to conduct foreign diplomacy and granted sovereignty to the states.[12] By 1779, both Congress and the states had accumulated considerable debt from the Revolutionary War, but the Articles of Confederation denied Congress the powers of taxation and regulation of foreign and interstate commerce.[1][13] Alexander Hamilton, along with many other Framers, believed the solution to this and problems of federal law enforcement could be solved with a strong general government.[1][14][15]

Alexander Hamilton greatly admired the British monarchy, and sought to create a similarly strong unitary executive in the United States.[16][17][18] One of the major influences on his thinking was political theorist, Jean-Louis de Lolme who praised the English monarchy for being "sufficiently independent and sufficiently controlled."[17][19] In Federalist No. 70, Hamilton cites De Lolme to support his argument that a unitary executive will have the greatest accountability to the people.[20] Hamilton was also inspired by William Blackstone and John Locke, who favored an executive who would act on his own prerogative while maintaining respect for constitutional obligations.[21][22] Montesquieu, Machiavelli, and Aristotle, all of whom argued for strength in the executive, also served as inspiration for the arguments in Federalist No. 70.[21][22] Hamilton's call for energy in the executive, as described in Federalist No. 70, mirrors Montesquieu's preference for "vigor" in the executive.[23][24]

During the Constitutional Convention in May 1787, Hamilton proposed a plan of government, dubbed the "British Plan," featuring a powerful unitary executive serving for life, or during good behavior.[19][25][26][27] Though this plan was rejected, James Wilson's proposal for a unitary executive, which Hamilton supported, was upheld with a vote of seven to three.[28] As part of the Federalists' effort to encourage the ratification of the Constitution, Hamilton published Federalist No. 70 to convince the states of the necessity of unity in the executive branch.[20]

Hamilton's arguments for a unitary executive

[edit]Federalist No. 70 argues in favor of the unitary executive created by Article II of the United States Constitution.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

According to Hamilton, a unitary executive is necessary to:

- ensure accountability in government

- enable the president to defend against legislative encroachments on his power

- ensure "energy" in the executive.[2][7][8]

Hamilton argues that a unitary executive structure will best permit purpose, direction, and flexibility in the executive branch—especially necessary during times of emergency and warfare.[4][5][11][29][30][31][32]

Accountability

[edit]According to Hamilton, a unitary executive is best-suited to promoting accountability in government because it is easier to point blame at one person than to distinguish fault among members of a group.[5][7][8][11] Because a unitary executive cannot "cloak" his failings by blaming council members, he has a strong incentive towards good behavior in office.[2][6][11] Accountability, made easier by the existence of a unitary executive, thus promotes effective and representative governance.[2][5][6]

Hamilton bolsters his argument by claiming that misconduct and disagreements among members of the council of Rome contributed to the Roman Empire's decline.[3][33] He warns at the end of Federalist No. 70 that America should be more afraid of reproducing the plural executive structure of Rome than of the "ambition of a single individual."[2]

Defense against encroachments

[edit]Beyond supporting a unitary executive, Hamilton recommends strength in the executive branch.[5][7][34] Hamilton justifies executive strength by claiming that the slow-moving Congress, a body designed for deliberation, will be best-balanced by a quick and decisive executive.[7][34] Hamilton also maintains that governmental balance can only be achieved if each branch of government (including the executive branch) has enough autonomous power such that tyranny of one branch over the others cannot occur.[5][7][35]

Energy

[edit]Alexander Hamilton writes that energy in the executive is "the leading character in the definition of good government."[2][4][36] Some scholars equate Hamiltonian "energy" to presidential "activity," while others describe energy as a president's eagerness to act on the behalf of his constituents.[6][7][37]

In Federalist No. 70, Hamilton lists four ingredients that constitute this energy:

Unity

[edit]Hamilton's core argument revolves around unity in the executive, meaning the Constitution's vesting of executive power in a single president by Article II of the United States Constitution.[1][6][38][39][40] His argument also centers upon unity's promotion of executive energy.[2][5][6][36][40] In Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton writes:

Those politicians and statesmen who have been the most celebrated for the soundness of their principles and for the justice of their views, have declared in favor of a single Executive... .They have with great propriety, considered energy as the most necessary qualification (of the former) and have regarded this as most applicable to power in a single hand...[2]

According to Hamilton, unity contributes to energy by permitting necessary "decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch" in the executive branch.[2][5][6][36][40] At the same time, a unitary executive is incentivized to act on behalf of his constituents.[2][7] As scholar Steven Calabresi writes, "a unitary executive would both cause power and energy to accrue to the office and facilitate public accountability for and control over how that power and energy was exercised."[7]

Duration

[edit]Hamilton also makes the case for duration, meaning a presidential term long enough to promote stability in the government.[2][5] While Hamilton elaborates on the importance of duration in Federalist No. 73, he argues briefly in Federalist No. 70 that the prospect of more time in office will motivate a president to act in concert with the views of the public.[2][6][7]

Support

[edit]Hamiltonian support can be defined as a presidential salary, which insulates government officials from corruption by attracting capable, honest men to office.[2][5][41] According to Hamilton, public service does not provide men with fame or glory, so ample pay is necessary to attract talented politicians.[2][41] Hamilton further expands upon his arguments for executive support in his essay Federalist No. 73.[2]

Competent powers

[edit]The President's competent powers, or his powers guaranteed by the Constitution, are mentioned in Federalist No. 70 and more fully discussed in Federalist No. 73 in the context of executive and legislative interactions, specifically the executive veto power.[2] Hamilton argues that the executive veto provides stability by preventing "the excess of lawmaking" [2][42] and that the executive veto and judicial review will "shield...the executive" from legislative misbehavior.[2][43] This argument is tied to Madison's praise of the separation of powers in Federalist No. 51, which he contends will permit the president to execute the laws and act as commander in-chief without fear of legislative encroachment on his powers.[2][43]

Scholars have differing views on the president's competent powers.[1][6][38][39][40] Proponents of the Unitary Executive Theory assert that all executive power is vested in the president, and that the President has "unilateral authority, impervious to congressional or judicial scrutiny."[39][44][45][46] Conversely, others read Article II of the United States Constitution as an "empty grant" that does not explicitly give the President the power to execute the laws.[38][46][47]

Contemporaneous opposition to the unitary executive

[edit]After Independence

[edit]

Resistance to the unitary executive began well before the emergence of the Anti-Federalist Papers.[48][49] After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, eleven of the thirteen states established constitutions to replace their charter governments.[49] In a reaction to colonial rule, most of these constitutions were primarily concerned with a declaration of rights and weakening executive power.[48] With the exception of New York, all of these states formed executive councils appointed by their respective legislatures.[49]

Virginia's Constitution of 1776 provided for an executive and an eight-member privy council elected by ballot in the bicameral legislature.[49] It mandated that the privy council be involved in nearly all executive decisions:

- Let a Privy Council, or Council of State, consisting of eight members, be chosen by joint ballot of both Houses of Assembly, promiscuously from their members, or the people at large, to assist in the administration of government. Let the Governour be President of this Council…[49]

Pennsylvania's 1776 Constitution, which lasted until 1790, provided for a Supreme Executive Council consisting of twelve members chosen by popular ballot.[49] The council and the unicameral legislature would elect a president from the members of the council, but the president would hold little authority over the council even in regards to military power.[48][49]

The Constitutional Convention

[edit]During the Constitutional Convention in 1787, several delegates opposed the unitary executive first recommended by James Wilson, and supported by Hamilton.[28][50][51] Both Charles Pinckney of South Carolina and Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania had suggested advisory councils that would serve as a support rather than a check on the executive.[50] Upon an invitation to dissent from Benjamin Franklin, who served as President of Pennsylvania's executive council, Roger Sherman of Connecticut stated his preference for the executive to be appointed by and directly accountable to the legislature, regardless of whether it was to be unitary or plural.[28][51] Before the vote to approve the unitary executive, Sherman also commented that advisory councils in the majority of the states and even in Great Britain served to make the executive acceptable to the people.[28]

Edmund Randolph, who had presented the Virginia Plan, was the most outspoken opponent of the unitary executive, arguing that it would be unpopular with the people and could easily become monarchical.[28][51] He warned against using the British government as a model for the Constitution, noting that energy, dispatch, and responsibility could be found in three men drawn from three different regions of the country just as well as in one.[28][51] The single executive was nonetheless approved by a vote of 7 to 3.[28]

Later in the convention, Hugh Williamson of North Carolina stated his preference for Randolph's suggestion that executive power be shared between three men representing three regions into which the states would be divided.[51] He argued that this triumvirate would be the best way to assure that neither the Northern nor the Southern states' interests would be sacrificed at the expense of the others'.[51]

The Anti-Federalist Papers and opposition to the Constitution

[edit]

While most of the Anti-Federalists' arguments did concern the presidency, some Anti-Federalist publications did directly contest Hamilton's position in Federalist 70 for unity in the executive branch.[52][53]

In response to the exclusion of an executive council in the Constitution, Mason published his "Objections to the Constitution" on November 22, 1787, in the Virginia Journal.[54] In this manuscript, originally written on the back of an early draft of the Constitution, Mason warned that the lack of a council would make for an unadvised president, who would act within the interests of friends, rather than the people at large:[54]

The President of the United States has no Constitutional Council, a thing unknown in any safe and regular government. He will therefore be unsupported by proper information and advice, and will generally be directed by minions and favorites...[54]

Richard Henry Lee, another prominent Anti-Federalist, exchanged letters with Mason, in which he too expressed concern about the unitary executive, supporting the constitutional addition of a privy council.[52][55] In Anti-Federalist No. 74, titled "The President as a Military King," Philadelphiensis (likely, Benjamin Workman) wrote primarily against the president's military powers, but added that the lack of a constitutional executive council would add to the danger of a powerful presidency:

And to complete his uncontrolled sway, [the President] is neither restrained nor assisted by a privy council, which is a novelty in government. I challenge the politicians of the whole continent to find in any period of history a monarch more absolute. . . .[56]

On December 18, 1787, after the Convention of Pennsylvania, which ultimately ratified the Constitution, the minority published its reasons for dissent to its constituents.[57] In this address, written most likely by Samuel Bryan and signed by twenty-one members of the minority, the lack of an executive council is enumerated as the twelfth of fourteen reasons for dissent:

12. That the legislative, executive, and judicial powers be kept separate; and to this end that a constitutional council be appointed, to advise and assist the president, who shall be responsible for the advice they give, hereby the senators would be relieved from almost constant attendance; and also that the judges be made completely independent.[57]

Though he was in England at the time of the Anti-Federalist Papers, Thomas Paine, whose pamphlet Common Sense served as motivation for independence from British rule during the American Revolution, also opposed the unitary executive.[58] While this position was already evidenced from his role as Clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly during the writing of Pennsylvania's 1776 Constitution,[59] he clearly stated it in a letter to George Washington in 1796.[58] In this letter, Paine argued for a plural executive on the grounds that a unitary executive would become head of a party and that a republic should not debase itself by obeying an individual.[58]

Hamilton's rebuttals to contemporaneous counterarguments

[edit]In Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton not only lays down an argument for a unitary executive, but also provides rebuttals to contemporaneous counterarguments in favor of a plural executive.[2] Hamilton employs historical examples and the rhetoric of common sense to warn the American people of the weaknesses of a plural executive structure.[3]

Unitary executive as a monarch

[edit]Hamilton anticipates and refutes the argument that a unitary executive is too similar to the British monarchy.[37] Some academics have noted that Hamilton viewed the British monarchy as a superior system of government and potential model for its consent for appointments and treaties.[5]

Governance by too few

[edit]Hamilton similarly anticipate and refutes the counterargument that more opinions in government lead to better decision-making.[2][5][11] In rejecting this view, Hamilton writes that a plural executive would actually "conceal faults and destroy responsibility" [2] and be a "clog" to the system.[2][11] He argues in Federalist No. 70 that a plural executive leads to a lack of accountability because there is no single person to blame for misconduct.[5][11] Furthermore, decision making becomes difficult because a council may propose an agenda contrary to that of the executive. Hamilton reminds the public that in times of warfare especially, the executive must not be slowed down by deliberation and disagreements.[5][7][11][34] Finally, he reminds America that a unitary executive structure promotes energy in the executive and that "duration" of the presidential term gives the executive a strong incentive to make policy in conformity with public opinion.[6][7][11] The executive will be held accountable to his constituents and act with "due dependence" and "due responsibility."[2] He claims that the two will foster liberty and "safety in the republican sense."[2][5][7][8][11][60]

Applications and modern relevance

[edit]Historical applications

[edit]Because Federalist No. 70 argues for a strong, unitary executive, it has often been used as a justification for expanding executive and presidential power, especially during times of national emergency.[5][29][30][31][32] For example, scholars have argued that Federalist No. 70 influenced:

- George Washington's declaration of neutrality towards Britain and France without Congressional Consent [32]

- Abraham Lincoln's decision to use executive authority to suspend Habeas Corpus and create a naval blockade without congressional approval during the American Civil War[5][61]

- Theodore Roosevelt's resolution to intervene in the Coal Strike of 1902[18]

- Woodrow Wilson's heavy use of executive power during and in the aftermath of World War I.[18]

The War on Terror

[edit]Federalist No.70 as a justification for executive power

[edit]

Federalist No. 70's arguments for an energetic, unitary executive are often cited in the context of national security.[29][62] After 9/11, executive power and secrecy took on a more central role in the pursuit of national security.[62] In this regard, members of the post 9/11 United States Department of Justice have argued that foreign policy is most effectively conducted with a single hand, meaning that Congress should defer to the president's authority.[29]

John Yoo, legal advisor to the Bush administration, has explicitly invoked Federalist No. 70 in his support for executive power over foreign policy.[29] Referencing Hamilton, Yoo has claimed that "the centralization of authority in the President is particularly crucial in matters of national defense, war, and foreign policy, where a unitary executive can evaluate threats, consider policy choices, and mobilize national resources with a speed and energy that is far superior to any other branch."[29] Yoo has also cited Federalist No. 70 in his support of the President's right to unilaterally conduct operations against terrorists without congressional consent.[29][31] He claims that this power applies to operations against both individuals and states.[29][31] At least one scholar has also argued that, because the president has the most access to national security information, only the president can know when the War on Terror is over and no longer mandates an expansive executive authority.[30]

President George W. Bush explicitly invoked the discourse of Federalist No. 70 in declaring that he was allowed to operate outside of the law when it conflicted with his prerogatives as the head of "the unitary executive branch."[5][63][64] For example, when signing the 2005 Detainee Treatment Act, Bush applied Hamilton's unitary executive theory to claim the right to work outside the provisions of the Act when they conflicted with his responsibilities as Commander in Chief.[63][64]

President Obama has also used signing statements to expand his executive power, specifically by issuing a 2011 statement on an omnibus year-end spending bill.[64][65] It has been speculated that this statement was made to nullify provisions of the bill that limited Obama's ability to deal with prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, thus expanding Obama's executive power.[65] This action has been explicitly compared to Bush's 2005 signing of the Detainee Treatment Act.[65]

Controversy

[edit]Not all scholars agree that Federalist No. 70 justifies the role that the President has played in the war on terror up to this point.[5] Some scholars contend that President Bush's foreign policy decisions exceeded his presidential powers granted by the Constitution.[5][66][67][68] Further, critics of the Bush Administration argue that any executive, as envisioned by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 70, must act within the limits imposed by other provisions of the United States Constitution[5][66][67][68] and that the concept of the unitary executive does not allow the president to work outside laws passed by Congress, even when they conflict with national security interests.[63][68] These critics argue that President Bush could have asked Congress to amend existing law or retroactively obtain warrants for surveillance and that he violated the constitution when he did not.[5][67][68] President Obama has been similarly criticized for operating outside the law, despite statements at the beginning of his presidency which showed a desire to limit the use of signing statements to expand executive power.[64][69][70]

One of Hamilton's primary arguments for a unitary executive was that it increases accountability for executive action, thereby protecting liberty.[5][7][8][11][60] Many have argued that the Bush administration's and Obama administration's use of secrecy and unilateral executive action has violated American liberty.[71][72][73][74] One scholar, James Pffifner, claims that if Hamilton were alive today, he would amend Federalist No. 70 to say that the "energy of the executive needs to be balanced by the 'deliberation and wisdom that only the legislature can provide.'"[5]

Judicial applications

[edit]Executive unity

[edit]Recently, Federalist No. 70 has become associated with Unitary Executive Theory, and has been invoked to support the claim that the president should have primary responsibility over the entire executive branch.[39] This theory was particularly relevant to Justice Antonin Scalia's 1988 dissent in the Supreme Court Case Morrison v. Olson, in which he argued that an investigation of the executive branch by independent counsel was unconstitutional because criminal prosecution was purely an executive power, held in its entirety by the president.[75] Scalia also cited Federalist No. 70 in his decision on Printz v. United States. Printz v. United States concerned the constitutionality of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, a federal law that would have obligated state law enforcement officers to help enforce federal gun regulations.[76][77] Scalia argued:

The Brady Act effectively transfers this responsibility to thousands of CLEOs [chief law enforcement officers] in the 50 States, who are left to implement the program without meaningful Presidential control (if indeed meaningful Presidential control is possible without the power to appoint and remove). The insistence of the Framers upon unity in the Federal Executive--to ensure both vigor and accountability--is well known. See The Federalist No. 70.[76]

Executive power

[edit]Federalist No. 70 has been cited in several Supreme Court dissents as a justification for the expansion of executive power.[78][79] For example, in his 1952 dissenting opinion in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, chief justice Fred M. Vinson wrote:

This comprehensive grant of the executive power to a single person was bestowed soon after the country had thrown the yoke of monarchy… Hamilton added: 'Energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks; it is not less essential to the steady administration of the law, to the protection of property against those irregular and high-handed combinations which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice...' It is thus apparent that the Presidency was deliberately fashioned as an office of power and independence. Of course, the Framers created no autocrat capable of arrogating any power unto himself at any time.[79]

Vinson referenced Federalist No. 70's arguments about energy in the executive to argue that the president should be allowed to seize private property in a time of national crisis.[80] In a more recent 2004 case, Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, Justice Clarence Thomas used Federalist No. 70 to make the case that the president should have the power to suspend Habeas Corpus for American citizens in order to fight the war on terror.[81][82]

In both cases, the majority of the court was not persuaded that the expansions in executive power in question were justified.[78][79][82]

Presidential accountability

[edit]Federalist No. 70 has also been cited by the Supreme Court as an authority on the importance of presidential accountability.[83] In its 1997 opinion in Clinton v. Jones, the court weighed whether or not a sitting president could delay addressing civil litigation until the end of his or her term.[83][84] The court cited Federalist No. 70, stating that the president must be held accountable for his or her actions, and thus cannot be granted immunity from civil litigation.[85] However, in the 2010 case of Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the court cited the need for executive accountability as a basis to expand presidential power.[86] Writing the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts stated:

The Constitution that makes the President accountable to the people for executing the laws also gives him the power to do so. That power includes, as a general matter, the authority to remove those who assist him in carrying out his duties. Without such power, the President could not be held fully accountable for discharging his own responsibilities; the buck would stop somewhere else. Such diffusion of authority "would greatly diminish the intended and necessary responsibility of the chief magistrate himself." The Federalist No. 70, at 478.[86]

Roberts argued that the act in question deprived the president of the ability to hold members of an independent board accountable, thus freeing him or her of responsibility over the independent board's actions and depriving the people of their ability to hold the president accountable.[86][87]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Prakash, Saikrishna Bangalore (1993). "Hail to the Chief Administrator: The Framers and the President's Administrative Powers". The Yale Law Journal. 102 (4): 991–1017. doi:10.2307/796838. hdl:20.500.13051/8746. JSTOR 796838. SSRN 2857499.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Hamilton, Alexander, et al. The Federalist. Vol. 43. Hackett Publishing, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Coenen, Dan T. (2006). "A Rhetoric for Ratification: The Argument of "The Federalist" and Its Impact on Constitutional Interpretation". Duke Law Journal. 56 (2): 469–543. JSTOR 40040551. SSRN 943412. Gale A157589903.

- ^ a b c d e Izquierdo, Richard Alexander (2013). "The American Presidency and the Logic of Constitutional Renewal: Pricing in Institutions and Historical Context from the Beginning". Journal of Law & Politics. 28 (3): 273–306. SSRN 2445614.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Pfiffner, James P. (2011). "Federalist No. 70: Is the President Too Powerful?". Public Administration Review. 71: S112–S117. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02470.x. JSTOR 41317425.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Arnold, Peri E. (2011). "Federalist No. 70: Can the Public Service Survive in the Contest Between Hamilton's Aspirations and Madison's Reality?". Public Administration Review. 71: S105–S111. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02469.x. JSTOR 41317424.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Calabresi, Steven G. (1995). "Some Normative Arguments for the Unitary Executive". Arkansas Law Review. 48: 23–104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Corwin, Edward Samuel. "President, office and powers." (1948).

- ^ a b Fatovic, Clement (July 2004). "Constitutionalism and Presidential Prerogative: Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian Perspectives". American Journal of Political Science. 48 (3): 429–444. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00079.x. JSTOR 1519908.

- ^ Paul Leicester Ford. "The Federalist",1898."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bailey, Jeremy D. (November 2008). "The New Unitary Executive and Democratic Theory: The Problem of Alexander Hamilton". American Political Science Review. 102 (4): 453–465. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080337. JSTOR 27644538. S2CID 144083358.

- ^ Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774-1781. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-299-00203-9.

- ^ Letter George Washington to George Clinton, September 11, 1783. The George Washington Papers, 1741–1799.

- ^ Bowen, Catherine (2010) [First published 1966]. Miracle at Philadelphia : the story of the Constitutional Convention, May to September 1787. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-10261-2.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-20085-8.

- ^ Mitchell, Broadus (1987). "Alexander Hamilton, Executive Power and the New Nation". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 17 (2): 329–343. JSTOR 40574455.

- ^ a b Scheuerman, William E. (2005). "American Kingship? Monarchical Origins of Modern Presidentialism". Polity. 37 (1): 24–53. doi:10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300001. hdl:10469/14228. JSTOR 3877061. S2CID 144479722.

- ^ a b c Loss, Richard (1982). "Alexander Hamilton and the Modern Presidency: Continuity or Discontinuity?". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 12 (1): 6–25. JSTOR 27547773.

- ^ a b Prakash, Saikrishna (February 1, 2000). "The Essential Meaning of Executive Power". University of Illinois Law Review. 2003: 701–820. doi:10.2139/ssrn.223757. SSRN 223757.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Alexander, et al. The Federalist Papers. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

- ^ a b Weaver, David R. (1997). "Leadership, Locke, and the Federalist". American Journal of Political Science. 41 (2): 420–446. doi:10.2307/2111771. JSTOR 2111771.

- ^ a b White, Jr., Richard D. (March 2000). "Exploring the Origins of the American Administrative State: Recent Writings on the Ambiguous Legacy of Alexander Hamilton". Public Administration Review. 60 (2): 186–190. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00077. JSTOR 977651.

- ^ Caldwell, Christopher. "Desperately Seeking Hamilton." Financial Times [London, England] 5 Mar. 2003, Comment & Analysis: 21. Print.[verification needed]

- ^ Montesquieu, Charles Baron De (2011). The Spirit of Laws. Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-61640-528-1.[page needed]

- ^ Fatovic, Clement (2013). "Reason and Experience in Alexander Hamilton's Science of Politics". American Political Thought. 2 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/666658. JSTOR 10.1086/666658. S2CID 145460632. SSRN 1580764.

- ^ Hoff, Samuel B. (1987). "A Bicentennial Assessment of Hamilton's Energetic Executive". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 17 (4): 725–739. JSTOR 27550481.

- ^ "Constitutional Topic: The Constitutional Convention". USConstitution.net. April 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Padover, Saul Kussiel (1970). To secure these blessings the great debates of the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Kraus Reprint Co. pp. 327–331. OCLC 654499147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Delahunty, Robert J; Yoo, John C. (Spring 2002). "The president's Constitutional authority to conduct military operations against terrorist organizations and the nations that harbor or support them". Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. 25 (2): 487–517. SSRN 331202.

- ^ a b c Mosier, Mark W. (2003). "The Power to Declare Peace Unilaterally". The University of Chicago Law Review. 70 (4): 1609–1637. doi:10.2307/1600583. JSTOR 1600583.

- ^ a b c d Yoo, John C. (2002). "War and the Constitutional Text". The University of Chicago Law Review. 69 (4): 1639–1684. doi:10.2307/1600615. JSTOR 1600615. SSRN 426862.

- ^ a b c Boylan, Timothy S. (September 2001). "The Law: Constitutional Understandings of the War Power". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 31 (3): 514–528. doi:10.1111/j.0360-4918.2001.00185.x. JSTOR 27552327. Gale A78545881.

- ^ Schultz, David (May 30, 2016). "Don't Know Much about History: Constitutional Text, Practice, and Presidential Power". University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy. 5 (1): 114–134.

- ^ a b c Newbold, Stephanie P.; Rosenbloom, David H. (November 2007). "Critical Reflections on Hamiltonian Perspectives on Rule-Making and Legislative Proposal Initiatives by the Chief Executive". Public Administration Review. 67 (6): 1049–1056. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00796.x. JSTOR 4624665.

- ^ Sundquist, James L. (1988). "Needed: A Political Theory for the New Era of Coalition Government in the United States". Political Science Quarterly. 103 (4): 613–635. doi:10.2307/2150899. JSTOR 2150899.

- ^ a b c Barber, Sotirios; Fleming, James (2009). "Constitutional Theory and the Future of the Unitary Executive". Emory Law Journal. 59 (2): 459–467.

- ^ a b Crockett, David A. (June 2004). "The Contemporary Presidency: Unity in the Executive and the Presidential Succession Act". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 34 (2): 394–411. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00050.x. JSTOR 27552591. Gale A119613611.

- ^ a b c Ledewitz, Bruce (1979). "The Uncertain Power of the President to Execute the Laws". Tennessee Law Review. 46 (4): 757–806. SSRN 1932735.

- ^ a b c d Pope, Paul James (2008). George W. Bush and the unitary executive theory: deconstructing unitary claims of unilateral executive authority (Thesis). OCLC 320474528. ProQuest 304405640.

- ^ a b c d Orentlicher, David (2013). Two Presidents Are Better Than One: The Case for a Bipartisan Executive Branch. NYU Press. doi:10.18574/9780814724682 (inactive November 1, 2024). ISBN 978-0-8147-8949-0. JSTOR j.ctt9qfv31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)[page needed] - ^ a b Bilmes, Linda J. (December 2011). "Federalist Nos. 67-77 How Would Publius Envision the Civil Service Today?". Public Administration Review. 71: s98–s104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02468.x. JSTOR 41317423.

- ^ Miller, Gary J.; Hammond, Thomas H. (1989). "Stability and Efficiency in a Separation-of-Powers Constitutional System". In Grofman, Bernard; Wittman, Donald A. (eds.). The Federalist Papers and the New Institutionalism. Algora Publishing. pp. 85–99. ISBN 978-0-87586-085-5.

- ^ a b Atkinson, Kory A. (2003). "In Defense of Federalism: The Need for a Federal Institutional Defender of State Interests". Northern Illinois University Law Review. 24 (1): 93–116. hdl:10843/21758.

- ^ Pierce, Richard J. (2009). "Saving the Unitary Executive Theory from Those Who Would Distort and Abuse it: A Review of the Unitary Executive, by Steven G. Calabresi and Christopher Yoo". University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 12 (2): 593–614. SSRN 1300939.

- ^ Krent, Harold J. (June 22, 2009). "The Unitary Executive: Presidential Power from Washington to Bush". Constitutional Commentary. 25 (3): 489–521. Gale A210168883.

- ^ a b Smith, Douglas G. (2001). "Separation of Powers and the Constitutional Text". Northern Kentucky Law Review. 28 (3): 595–611. SSRN 772266.

- ^ Rosenberg, Morton (1981). "Beyond the Limits of Executive Power: Presidential Control of Agency Rulemaking under Executive Order 12,291". Michigan Law Review. 80 (2): 193–247. doi:10.2307/1288047. JSTOR 1288047.

- ^ a b c Williams, Robert F. (1988). "Evolving State Legislative and Executive Power in the Founding Decade". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 496 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1177/0002716288496001005. JSTOR 1046317. S2CID 154703306.

- ^ a b c d e f g Blunt, Barrie E. (1990). "Executive constraints in state constitutions under the Articles of Confederation". Public Administration Quarterly. 13 (4): 451–469. JSTOR 40862258. ProQuest 1294842625.

- ^ a b Hoxie, R. Gordon (1985). "The Presidency in the Constitutional Convention". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 15 (1): 25–32. JSTOR 27550162.

- ^ a b c d e f Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-726-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b Wrabley, Raymond B. (1991). "Anti-Federalism and the Presidency". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 21 (3): 459–470. JSTOR 27550766.

- ^ Riccards, Michael P. (1977). "The Presidency and the Ratification Controversy". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 7 (1): 37–46. JSTOR 27547327.

- ^ a b c Mason, George. "Objections to the Constitution of Government formed by the Convention." The Essential Antifederalist. By W. B. Allen, Gordon Lloyd, and Margie Lloyd. Lanham: UP of America, 1985. 12. Print.[page needed][verification needed]

- ^ Lee, Richard Henry. The Essential Antifederalist. By W. B. Allen, Gordon Lloyd, and Margie Lloyd. Lanham: UP of America, 1985. 12. Print.[page needed][verification needed]

- ^ Philadelphiensis (2009). "The President as Military King". The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 704. ISBN 978-1-4495-7883-1.

- ^ a b "The Address and Reasons for Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of Pennsylvania." The Essential Antifederalist. By W. B. Allen, Gordon Lloyd, and Margie Lloyd. Lanham: UP of America, 1985. 12. Print.[page needed][verification needed]

- ^ a b c Merriam, C. E. (1899). "Thomas Paine's Political Theories". Political Science Quarterly. 14 (3): 389–403. doi:10.2307/2139704. JSTOR 2139704. ProQuest 137486688.

- ^ Tietjen, Gregory. Introduction. Common Sense. By Thomas Paine. N.p.: Fall River, 2013. vii-xxxi. Print.

- ^ a b Berry, Christopher R.; Gersen, Jacob E. (2008). "The Unbundled Executive". The University of Chicago Law Review. 75 (4): 1385–1434. JSTOR 27653959. SSRN 1113543.

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (1988). "Abraham Lincoln and Federalism". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 10 (1): 1–46. hdl:2027/spo.2629860.0010.103.

- ^ a b Stone, Geoffrey R. (December 21, 2013). "Protecting the nation while upholding our civil liberties". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Erin (2006). "Reinterpreting Torture: Presidential Signing Statements and the Circumvention of U.S. and International Law". Human Rights Brief. 14 (1): 21–24. SSRN 1309884.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Phillip J. (September 2005). "George W. Bush, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Use and Abuse of Presidential Signing Statements". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 35 (3): 515–532. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.546.460. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2005.00262.x. JSTOR 27552703. Gale A136262639.

- ^ a b c Crouch, Jeffrey; Rozell, Mark J.; Sollenberger, Mitchel A. (December 2013). "The Law : President Obama's Signing Statements and the Expansion of Executive Power: President Obama". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 43 (4): 883–899. doi:10.1111/psq.12071. hdl:2027.42/100285. JSTOR 43285355. Gale A350575074.

- ^ a b Mayer, Jane (2009). The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How The War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-45650-2.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Kreimer, Seth (2003). "Too Close to the Rack and the Screw: Constitutional Constraints on Torture in the War on Terror". University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 6 (2): 278–325.

- ^ a b c d Chemerinsky, Erwin (2006). "The Assault on the Constitution: Executive Power and the War on Terrorism". U.C. Davis Law Review. 40 (1): 1–20.

- ^ Garvey, Todd (June 2011). "The Law: The Obama Administration's Evolving Approach to the Signing Statement". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 41 (2): 393–407. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2011.03860.x. JSTOR 23884838. Gale A254825813.

- ^ Korzi, Michael J. (May 2011). "'A Legitimate Function': Reconsidering Presidential Signing Statements". Congress & the Presidency. 38 (2): 195–216. doi:10.1080/07343469.2011.576222. S2CID 153909187.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (February 5, 2013). "Chilling legal memo from Obama DOJ justifies assassination of US citizens". The Guardian.

- ^ Harper, Jim (February 17, 2006). "Secrecy Fetish Hurts Terror War". Cato Institute.

- ^ "American Civil Liberties Union." American Civil Liberties Union. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Apr. 2014.[verification needed]

- ^ Bartosiewicz, Petra (December 7, 2012). "A permanent war on terror". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hollis-Brusky, Amanda (January 1, 2011). "Helping Ideas Have Consequences: Political and Intellectual Investment in the Unitary Executive Theory, 1981-2000". Denver Law Review. 89 (1): 197–244.

- ^ a b Printz v. U.S. Supreme Court of the United States. 27 June 1997. Find Law. Web. 13 Apr. 2014. http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=521&invol=898.

- ^ PRINTZ v. UNITED STATES. The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. 11 April 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1996/1996_95_1478

- ^ a b Simon, Kelly E. (Spring 2003). "Hamdi v. Rumsfeld". Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. 17 (3): 511–514.

- ^ a b c 343 U.S. 579; 72 S. Ct. 863; 96 L. Ed. 1153; 1952 U.S. LEXIS 2625; 21 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P67,008; 1952 Trade Cas. (CCH) P67,293; 62 Ohio L. Abs. 417; 47 Ohio Op. 430; 26 A.L.R.2d 1378; 30 L.R.R.M. 2172. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2014/04/13.

- ^ Westin, Alan F. (1990). The Anatomy of a Constitutional Law Case: Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. V. Sawyer (the Steel Seizure Decision). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07334-9.[page needed]

- ^ Anderson, James B. (March 22, 2005). "Hamdi v. Rumsfeld: judicious balancing at the intersection of the executive's power to detain and the citizen-detainee's right to due process". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 95 (3): 689–724. JSTOR 3491324. Gale A135705820.

- ^ a b Perkin, Jared (March 1, 2005). "Habeas Corpus in the War Against Terrorism: Hamdi v. Rumsfeld and Citizen Enemy Combatabts". Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law. 19 (2): 437–471.

- ^ a b LEXIS 3254; 65 U.S.L.W. 4372; 73 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1548; 73 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1549; 70 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) P44,686; 97 Cal. Daily Op. Service 3908; 97 Daily Journal DAR 6669; 10 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 499. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2014/04/13.

- ^ CLINTON v. JONES. The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. 12 April 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1996/1996_95_1853#opinion

- ^ Kasten, Martin (1998). "Summons at 1600: Clinton v. Jones' Impact on the American Presidency". Arkansas Law Review. 51 (3): 551–574.

- ^ a b c 130 S. Ct. 3138; 177 L. Ed. 2d 706; 2010 U.S. LEXIS 5524; 78 U.S.L.W. 4766; 22 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 685. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2014/04/13.

- ^ FREE ENTERPRISE FUND v. PUBLIC COMPANY OVERSIGHT BOARD. The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. 06 April 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2009/2009_08_861