Energy policy in Hawaii, 2001-2017

This article does not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

Energy policy involves governmental actions affecting the production, distribution, and consumption of energy in a state. Energy policies are enacted and enforced at the local, state, and federal levels and may change over time. These policies include legislation, regulation, taxes, incentives for energy production or use, standards for energy efficiency, and more. Stakeholders include citizens, politicians, environmental groups, industry groups, and think tanks. A variety of factors can affect the feasibility of federal and state-level energy policies, such as available natural resources, geography, and consumer needs.

This article outlines state-level oil and gas regulations, renewable energy programs, oil and gas production, energy usage, energy and electricity prices, fuel taxes, and utilities in Hawaii.

See the tabs below for further information:

- Policy: This tab provides information about state regulations on energy production and policies related to oil and gas production, fracking, renewable energy generation, energy efficiency, and net metering.

- Production: This tab provides information about total energy production by energy source in Hawaii.

- Usage: This tab presents information about electricity consumption by energy source.

- Prices and taxes: This tab presents information about average energy and electricity prices, per capita spending on energy, and fuel taxes.

- Utilities: This tab presents information about public and private utilities, electricity markets, the types of utilities in Hawaii, and the electric reliability organizations in Hawaii.

- Background: This tab provides information about the types of nonrenewable and renewable energy sources produced and used in the United States, an energy profile of Hawaii, a state profile of Hawaii from the Almanac of American Politics (2016), and economic indicators in the state, such as median income.

Policy

State regulations

As of 2015, Hawaii did not have proven crude oil or natural gas reserves, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. As such, the state did not have rules and regulations governing oil and gas production in Hawaii.[1]

Renewable energy policies

States have implemented funding and financial incentive programs to subsidize or otherwise increase investment in renewable energy resources such as wind, solar, and hydroelectric power. These programs include renewable portfolio standards, grants, rebate programs, tax incentives, loans, performance-based incentives, and more. The aim of the policies generally involves reducing the cost of renewable energy production for consumers, reducing regulatory compliance costs, reducing investment risks involving renewable energy, and/or increasing the adoption of renewable energy sources by individuals and businesses.[2]

Renewable Portfolio Standard

- See also: Renewable Portfolio Standard

A Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), also known as a renewable electricity standard, is a mandate intended to increase the amount of renewable energy production and use. Under these standards, a utility company can be required by a state to have a certain percentage of its electricity come from certain renewable energy resources. In addition, states may give tax credits to utility companies to fulfill these requirements.[3][4]

As of February 2017, Hawaii was one of 30 states with a Renewable Portfolio Standard. The Hawaii State Legislature enacted a renewable portfolio goal in 2001 and an enforceable Renewable Portfolio Standard in 2004. Each electric utility that sells electricity for consumption in the state must procure the following percentages of its net electricity sales from renewable energy sources:[5][6][7][8]

- 10 percent by December 31, 2010

- 15 percent by December 31, 2015

- 30 percent by December 31, 2020

- 40 percent by December 31, 2030

- 70 percent by December 31, 2040

- 100 percent by December 31, 2045

Utilities may count existing renewable resources in their totals. Additionally, utility companies and their utility affiliates can aggregate their renewable energy output to meet the above targets. The Hawaii Public Utilities Commission has regulatory authority over these utilities and enforces the standard. The commission can penalize utilities that do not meet the standard.[6][7][8]

Eligible renewable energy sources include any electricity generated or produced by the sun, falling water, landfill biogas, geothermal power, ocean currents and waves, biomass, biofuels such as ethanol, and hydrogen produced from renewable sources. Electricity generated from renewable sources must be customer-sited and connected to the electric grid.[6][7][8]

Grant programs

States, nonprofit organizations, and/or private utilities may operate grant programs for renewable energy. These programs may include state or private funding for energy installation costs, research and development, infrastructure and business development, system testing, and renewable energy feasibility studies (studies that look into the potential for renewable energy use in specific areas). Grants can be provided with or without requiring a recipient to match the grant. Additional incentives, such as lower interest loans, may be included with a grant.[2]

As of February 2017, Hawaii was one of nine states with utility-run and/or locally run grant programs for renewable energy. A complete list of state, local, and private incentive, loan, grant, and assistance programs for renewable energy and energy efficiency in Hawaii can be found here.

Loan programs

Loan programs may be used to offer lower interest loans or other financing options to individuals and businesses to reduce the upfront costs of purchasing and installing renewable energy technologies. Loan programs may include programs that use payments from earlier borrowers to provide loans for new borrowers, programs in which building owners reduce their energy consumption to pay their upfront costs for renewable energy technologies, and programs that allow individuals with a higher debt-to-income ratio to purchase homes that use less energy, among others.[2]

As of March 2015, Hawaii was one of 24 states with a state-run loan program and locally run, utility-run, and/or privately run loan programs for renewable energy.[2]

A complete list of state, local, and private incentive, loan, grant, and assistance programs for renewable energy and energy efficiency in Hawaii can be found here.

GreenSun Hawaii

The GreenSun Hawaii program was established in 2009 using federal funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. The program allows Hawaii lenders, such as banks and credit unions, to issue loans for renewable energy systems and energy efficiency measures. Individual homeowners can receive loans for solar water heating systems and photovoltaic solar energy systems. Non-residential owners may receive loans for lighting, air conditioning, solar water heating systems, photovoltaic solar energy systems, and windows. Non-residential property owners must complete an energy audit to be eligible for loans. Loan terms differ depending on the lender.[2][9]

See the map below for renewable energy loan programs by state.

In 2008, the Hawaii State Legislature enacted HB 2261, which established a renewable energy loan program for agriculture. Farmers can receive loans for photovoltaic solar energy systems, hydroelectric power projects, wind energy, methane generation, ethanol and biodiesel production. Loans may be issued for up to $1.5 million or up to 85 percent of a project's cost for a loan term of up to 40 years. Eligible applicants include qualified farmers with a minimum credit rating and an ability to repay the loan. Renewable energy loans for agriculture carried 3 percent interest rate as of 2014.[10]

Energy efficiency regulations

As of February 2017, Hawaii required new residential and commercial buildings to meet energy efficiency standards. In 2009, the Hawaii Building Code Council adopted the 2006 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), which outlines energy efficiency standards on heating, ventilating, air conditioning, water heating, and lighting in buildings. In 2016, the council adopted to the 2015 version of IECC, which can be found here.[5][11][12]

In 2006, the Hawaii State Legislature enacted HB 2175, which required energy efficiency measures at state facilities. The law requires state buildings, including new residential facilities that receive state funding, to meet insulation standards, adopt high-performance windows, and if feasible implement measures to maximize natural ventilation. State agencies are required to adopt energy and water conservation practices and purchase energy efficient equipment. In 2009, the legislature enacted HB 1464, which required state agencies to evaluate the energy efficiency of all state buildings larger than 5,000 square feet or buildings that use more 8,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year by the end of 2010. In addition, the law requires that every five years buildings should be retro-commissioned (during which operating and mainteance systems must be examined and equipment may be replaced or repaired)[13]

Net metering

Net metering is a billing system in which customers who generate their own electricity, usually using renewable sources (such as solar panels) are able to sell their excess electricity back to the electric grid, which is an interconnected network that is used to deliver electricity. This requires electricity to be able to flow both to and from a consumer.[14][15][16]

As of October 2016, Hawaii was one of seven states without a statewide net metering policy. Prior to this date, Hawaii had a net metering policy, which was first enacted in 2001. In October 2015, the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission voted to end the net metering policy for new customers. The commission voted for distributed generation compensation regulations in lieu of net metering. For a complete list of net metering programs by state, click here.[5][17][18][19]

Recent legislation

The following is a list of recent energy policy bills that have been introduced in or passed by the Hawaii State Legislature. To learn more about each of these bills, click the bill title. This information is provided by BillTrack50 and LegiScan.

Note: Due to the nature of the sorting process used to generate this list, some results may not be relevant to the topic. If no bills are displayed below, no legislation pertaining to this topic has been introduced in the legislature recently.

Ballot measures

Energy policy ballot measures

- See also: Energy on the ballot and List of Hawaii ballot measures

Ballotpedia has covered 1 ballot measures relating to state and local energy policy in Hawaii.

Utility policy ballot measures

- See also: Local utility tax and fees on the ballot

Ballotpedia has not covered any ballot measures relating to local utility tax and fees in Hawaii.

Production

The sections below include statistics on total energy production in Hawaii, oil and natural gas production in Hawaii, oil and gas production in Hawaii over time (2004-2014), and oil and gas production on federal land, including the amount of federal land leased in Hawaii for production.

Total energy production

The table below provides information regarding energy production in Hawaii in British thermal units (Btu). A British thermal unit is used to measure the heat contained in different fuels. The U.S. Department of Energy defines a Btu as "the quantity of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 pound of liquid water by 1 degree Fahrenheit." Fuels are discussed in terms of Btu to compare fuels with different energy content and prices. For example, one gallon of gasoline equals 120,524 Btu.[20]

| Energy production, 2014 (in billion Btu) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Biomass | Coal | Crude oil | Nuclear energy | Natural gas | Renewable | Total* | |

| Hawaii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27,166 | 27,166 | |

| Alaska | 0 | 22,944 | 1,050,815 | 0 | 381,633 | 19,737 | 1,475,129 | |

| Oregon | 5,844 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 974 | 478,961 | 485,779 | |

| Washington | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99,332 | 0 | 928,071 | 1,027,403 | |

| U.S. average | 38,759 | 404,181 | 307,301 | 160,980 | 585,731 | 187,132 | 1,684,085 | |

| *Total figures were computed by Ballotpedia. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | ||||||||

Nonrenewable energy production

The table below provides information regarding nonrenewable energy production in Hawaii. For coal data, the phrase productive capacity refers to the maximum amount of coal that could be expected to be produced in 2014. The natural gas and crude oil production data refer to the amounts of natural gas and crude oil produced in December 2014 and April 2016, respectively.[1][21]

| Nonrenewable energy production | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Coal, productive capacity (short tons) |

Natural gas (million cubic feet) |

Crude oil (thousand barrels) |

| Date | 2014 | December 2014 | April 2016 |

| Hawaii | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alaska | 3,000,000 | 29,976 | 14,667 |

| Oregon | 0 | 80 | 0 |

| Washington | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| U.S. average | 24,874,314 | 43,350 | 4,388 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | |||

Oil and gas production (2004-2014)

Note: This section provides information about oil and gas production on private and state-owned lands. Information on oil and gas production on federal lands is accessible here.

Because Hawaii had no crude oil or natural gas reserves as of 2015, there was no oil or gas production in the state.[1]

Energy usage

The section below includes statistics on electricity consumption in the state by energy type (in 2014).

Consumption

The table below provides information about energy consumption by source in Hawaii in 2014. Information from select surrounding states is provided for comparison.[1]

| Energy consumption in Hawaii, 2014 (in billion Btu) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Coal | Crude oil and petroleum products | Natural gas | Nuclear energy | Solar | Wind | Geothermal | Hydropower | Wood and wood waste | Biomass |

| Hawaii | 17,241 | 236,620 | 2,805 | 0 | 10,650 | 5,503 | 2,422 | 895 | 7,697 | 10,950 |

| Alaska | 18,225 | 235,572 | 329,585 | 0 | 10 | 1,445 | 186 | 14,633 | 3,463 | 5,476 |

| Oregon | 34,238 | 339,434 | 225,576 | 0 | 3,585 | 71,852 | 2,977 | 335,341 | 59,361 | 72,449 |

| Washington | 76,547 | 715,873 | 319,784 | 99,332 | 875 | 69,117 | 1,136 | 755,695 | 101,249 | 121,119 |

| U.S. average | 359,931 | 716,746 | 544,353 | 172,585 | 20,739 | 531,323 | 16,555 | 61,397 | 65,345 | 101,581 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | ||||||||||

Prices and taxes

The sections below include information on energy prices and spending in Hawaii, fuel taxes and state taxes in Hawaii and in neighboring states, and an overview of the federal tax on gasoline.

Energy prices

The price of electricity is affected by supply and demand. The supply of electricity is affected by fuel prices, environmental and energy regulations, power plant capacity, weather, and other factors. Demand for electricity also affects the price. Because electricity cannot be stored for long periods of time, it must be produced and used when it is needed. As demand for electricity increases, the price also generally increases.[22][23]

The table below provides information about energy prices in Hawaii as of April 2016. Information from select surrounding states is provided for comparison.[1]

| Energy prices in Hawaii | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Natural gas Dollars per thousand cubic foot |

Electricity Cents per kilowatthour |

| Date | April 2016 | April 2016 |

| Hawaii | $36.85 | 22.7 |

| Alaska | $9.63 | 18.6 |

| Oregon | $13.70 | 8.7 |

| Washington | $9.50 | 7.6 |

| U.S. average | $11.20 | 10.41 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | ||

Electricity prices can vary depending on the type of consumer; consumer categories include residential, commercial, industrial, and in some cases, transportation. The rate-making process is both political and economic. The table below presents information about electricity prices by consumer type in Hawaii in April 2016. Information from select surrounding states is provided for comparison.

| Electricity prices in Hawaii by sector (in cents per kilowatthour) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Commercial | Industrial | Residential | Transportation | Average (all sectors) |

| Date | April 2016 | April 2016 | April 2016 | April 2016 | April 2016 |

| Hawaii | 23.3 | 19.3 | 26.9 | 0.0 | 23.2 |

| Alaska | 18.4 | 16.1 | 20.7 | 0.0 | 18.4 |

| Oregon | 8.9 | 5.8 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 8.6 |

| Washington | 8.3 | 4.4 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 7.7 |

| U.S. average | 10.48 | 7.45 | 13.05 | 10.47 | 10.36 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | |||||

Energy spending

The table below provides information about energy spending in Hawaii as of 2014. Information from select surrounding states is provided for comparison.

| Energy spending in Hawaii, 2014 (in millions of dollar except per capita spending) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Petroleum | Coal | Natural gas | Nuclear | Per capita spending |

| Hawaii | $5,417 | $45 | $117 | $0 | $5,195 |

| Alaska | $5,537 | $89 | $481 | $0 | $9,349 |

| Oregon | $9,426 | $87 | $1,498 | $0 | $3,744 |

| Washington | $17,219 | $200 | $2,158 | $79 | $3,653 |

| U.S. average | $17,267 | $1,322 | $3,786 | $574 | $5,304 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Google Sheets API" | |||||

Fuel taxes

Revenue collected by federal, state, and local governments from fuel taxes is usually used to fund transportation infrastructure such as roads and bridges. Some states may charge an excise tax based on how much gas or diesel is purchased. Some states may charge retail tax based on the average price of gas over a certain period. Additionally, some states may charge an environmental tax to be used for environmental projects. The Tax Foundation, which created the map to the right, used data from the American Petroleum Institute, which converted each state's different tax structure into cents per gallon to compare each state's gas taxes. In 2016, gas taxes accounted for 23 percent of the price of gasoline. Crude oil accounted for 40 percent of the price of gasoline, refining accounted for 24 percent of the price, and distribution and marketing accounted for 13 percent of the remainder.[24][25]

The table below provides information about state fuel taxes by type (excluding the federal gas taxes) in Hawaii as of January 2016. As of January 2016, Hawaii levied a 42.4 cent state gasoline tax and a 39.6 cent state diesel tax. Hawaii ranked fourth highest in total gasoline taxes (federal and state) and fifth highest in total diesel fuel taxes as of January 2016.[26][27]

| State motor fuel taxes in cents per gallon, January 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | State gasoline tax | Total gasoline tax | Rank | State diesel tax | Total diesel tax | Rank |

| Hawaii | 42.4 | 60.8 | 4 | 39.6 | 64.0 | 5 |

| Alaska | 12.3 | 30.7 | 50 | 12.8 | 37.2 | 50 |

| Oregon | 31.1 | 49.5 | 16 | 30.4 | 54.8 | 20 |

| Washington | 44.5 | 62.9 | 2 | 44.5 | 68.9 | 3 |

| U.S. average | 30.29 | 48.69 | N/A | 30.01 | 54.41 | N/A |

| Source: American Petroleum Institute, "Motor Fuel Taxes" | ||||||

Federal tax

The first federal tax on gasoline was proposed by Secretary of the Treasury Ogden L. Mills under President Herbert Hoover (R) as a revenue generating measure to balance the budget during the Great Depression. A 1-cent tax per gallon of imported gasoline and fuel oil was passed as part of the Revenue Act of 1932 and signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (D). The 1-cent tax continued until 1951 when the tax was increased to 2 cents in part to raise revenue during the Korean War. In 1956, the tax was raised to 3 cents to fund the Interstate Highway System. During this time, the Highway Trust Fund was created as a means to fund highway construction. Since 1956, there have been increases to the tax. As of April 2016, the gas tax was last raised by President Bill Clinton (D) in 1993 to 18.4 cents per gallon.[28]

Utilities

The sections below include general information on utilities, an overview of utilities and electricity markets, information on the types of utilities in Hawaii, an overview of electricity reliability organizations (EROs), and the EROs that oversee electricity in Hawaii.

Background

Utilities are firms that own and/or operate facilities to generate, transmit, and/or distribute electricity, gas, and/or water to the public. Electric utilities are commercial entities that own and operate facilities to generate, transmit, and distribute electricity to the public and/or the industrial sector. State and local regulators oversee transmission and distribution charges. Local utilities read electric meters and bill individuals or businesses, generally on a monthly basis.[29][30]

Utilities are defined differently in each state and in federal legislation. Two general types of utilities are private and public utilities. Private utilities, commonly known as investor-owned utilities, provide stocks to investors and sell bonds. These utilities are regulated by state regulatory agencies. State agencies are also responsible for setting retail rates charged by investor-owned utilities, overseeing utility infrastructure, and ensuring that investor-owned utilities respond to customer service demands. Public utilities include government or municipally owned utilities. Another type of utility is an electric cooperative. Cooperatives are nonprofit businesses voluntarily owned and managed by the individuals and businesses that use their services. They are commonly used in rural areas that do not have access to a larger state or region-wide electric grid.[30]

Electricity markets

Electricity markets in each state are defined as regulated or deregulated. A regulated market includes utilities that own and manage the power plants that generate the electricity, the electricity transmission lines, and the distribution equipment (such as wires and electric poles). In addition, the utilities rates are approved and regulated by local and state agencies. A deregulated market requires utilities to divest ownership in the generation and transmission of electricity. In this market, utilities oversee the interconnection from a meter at a household or business to the power grid and is responsible for billing ratepayers.[31][32]

Depending on the state and/or area, public utilities may provide most or all energy services to homes and businesses, or a state may allow other private electricity providers to transmit and distribute electricity in addition to other utilities. For example, one type of private provider is a retail energy provider, which sells electricity in areas with retail competition. The provider purchases wholesale electricity and the delivery services (such as transmission lines) and can price electricity to particular consumers.[31][32]

As of February 2017, Hawaii was one of 40 states with a regulated electricity market. The Hawaii Public Utilities Commission has regulatory authority over four electric utilities: the Hawaii Electric Light Company, the Maui Electric Company, the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, and the Hawaiian Electric Company. Hawaii's six main islands each have an electric grid that is not connected to another island. The statutes, administrative rules, and general orders covering the state's electric utilities can be found here.[33][34]

Electric reliability organizations

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 required the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to designate an electric reliability organization (ERO) for the United States. An ERO oversees the reliability of a nation's electric grid. In 2006, FERC granted authority to the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) to develop and enforce grid reliability standards for the United States. NERC, a self-regulated nonprofit corporation, is authorized to enforce grid reliability standards for all users, owners, and operators of the U.S. electrical system.[35]

NERC works with eight regional reliability organizations to oversee the U.S. electrical system. These organizations, known as regional entities, are composed of officials from investor-owned utilities, federal power agencies, electric cooperatives, and state and municipal utilities. Regional entities enforce NERC and regional reliability standards. Further, they forecast electricity demand and coordinate operations with other regional entities.[36]

Hawaii EROs

As of February 2017, neither Hawaii nor Alaska had a NERC-affiliated regional electricity reliability organization and was exempt under the Federal Power Act as amended in 2005.[37]

Background

The sections below include an overview of the types of renewable and nonrenewable energy produced and consumed in the United States, an energy profile of Hawaii (from the U.S. Energy Information Administration), a general profile of Hawaii (from the 2016 edition of the Almanac of American Politics), and various economic indicators in Hawaii.

Background on energy resources

Nonrenewable energy sources, such as coal, oil, and natural gas (sometimes known as fossil fuels), and renewable sources, such as hydropower, wind, biofuels, and solar energy, are produced in each state, though at different levels depending on a state's geography, energy consumption, and the raw materials available in a particular state. For example, several states do not have coal, oil, and/or natural gas resources. States that lack these resources import these fuels.[38]

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, oil, coal, and natural gas comprise the majority of the resources used to generate power in the United States. In 2014, the top five energy-producing states were the top five fossil fuel-producing states—Texas, Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, and West Virginia. These states' fossil fuel production accounted for approximately 42 percent of U.S. energy production in 2014. States with fewer coal, oil, and natural gas resources generally consume less energy. In 2014, the bottom five energy-producing states—Rhode Island, Delaware, Hawaii, Nevada, and New Hampshire—produced 0.2 percent of U.S. energy and consumed approximately 2 percent of total U.S. energy.[38]

The production of biofuels (liquid fuels created from plant or plant-derived materials) is generally concentrated in the Midwest—states such as Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, and South Dakota) given the region's agricultural production of crops such as corn, which is used to make ethanol, a biofuel that can be blended with gasoline and used as a transportation fuel.[38]

Other renewable sources are used to generate power in the states include hydroelectric power, which accounted for about half of all renewable energy production in the United States in 2014.[38]

Hawaii energy profile

As of 2015, approximately 80 percent of Hawaii's energy came from petroleum, and Hawaii was ranked first among the 50 states in petroleum consumption. In 2015, the Hawaii State Legislature enacted a standard requiring that the state receive 100 percent of its electricity from renewable energy sources by the year 2045. Hawaii has no proven petroleum, coal, or natural gas reserves and thus has no fossil fuel production.[1]

In 2014, net electricity generation from petroleum-fired power plants in Hawaii fell below 70 percent for the first time. That year, wind energy, solar energy, biomass, and geothermal energy accounted for approximately 13 percent of Hawaii's electricity.[1]

In 2015, the state legislature extended Hawaii's Renewable Portfolio Standard to require that 40 percent of the state's net electricity generation come from renewable energy sources by the year 2030 and 100 percent by the year 2045.[1]

State profile

| Demographic data for Hawaii | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hawaii | U.S. | |

| Total population: | 1,425,157 | 316,515,021 |

| Land area (sq mi): | 6,423 | 3,531,905 |

| Race and ethnicity** | ||

| White: | 25.4% | 73.6% |

| Black/African American: | 2% | 12.6% |

| Asian: | 37.7% | 5.1% |

| Native American: | 0.2% | 0.8% |

| Pacific Islander: | 9.9% | 0.2% |

| Two or more: | 23.7% | 3% |

| Hispanic/Latino: | 9.9% | 17.1% |

| Education | ||

| High school graduation rate: | 91% | 86.7% |

| College graduation rate: | 30.8% | 29.8% |

| Income | ||

| Median household income: | $69,515 | $53,889 |

| Persons below poverty level: | 11.6% | 11.3% |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, "American Community Survey" (5-year estimates 2010-2015) Click here for more information on the 2020 census and here for more on its impact on the redistricting process in Hawaii. **Note: Percentages for race and ethnicity may add up to more than 100 percent because respondents may report more than one race and the Hispanic/Latino ethnicity may be selected in conjunction with any race. Read more about race and ethnicity in the census here. | ||

Presidential voting pattern

- See also: Presidential voting trends in Hawaii

Hawaii voted for the Democratic candidate in all seven presidential elections between 2000 and 2024.

More Hawaii coverage on Ballotpedia

- Elections in Hawaii

- United States congressional delegations from Hawaii

- Public policy in Hawaii

- Endorsers in Hawaii

- Hawaii fact checks

- More...

Economic indicators

- See also: Economic indicators by state

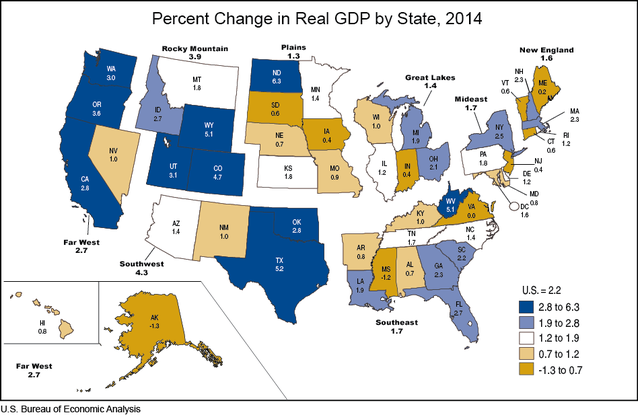

Broadly defined, a healthy economy is typically one that has a "stable and strong rate of economic growth" (gross state product, in this case) and low unemployment, among many other factors. The economic health of a state can significantly affect its healthcare costs, insurance coverage, access to care, and citizens' physical and mental health. For instance, during economic downturns, employers may reduce insurance coverage for employees, while those who are laid off may lose coverage altogether. Individuals also tend to spend less on non-urgent care or postpone visits to the doctor when times are hard. These changes in turn may affect the decisions made by policymakers as they react to shifts in the industry. Additionally, a person's socioeconomic status has profound effects on their access to care and the quality of care received.[39][40][41]

Hawaii’s median annual household income was $60,814 from 2011 to 2013, highest among neighboring states. Hawaii also had the lowest unemployment rate as of September 2014.[42][43][44][45]

Note: Gross state product (GSP) on its own is not necessarily an indicator of economic health; GSP may also be influenced by state population size. Many factors must be looked at together to assess state economic health.

| Various economic indicators by state | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Distribution of population by FPL* (2013) | Median annual income (2011-2013) | Unemployment rate | Total GSP (2013)† | ||||

| Under 100% | 100-199% | 200-399% | 400%+ | Sept. 2013 | Sept. 2014 | |||

| Hawaii | 11% | 16% | 35% | 38% | $60,814 | 4.7% | 4.2% | $75,235 |

| California | 15% | 21% | 28% | 36% | $57,161 | 8.8% | 7.3% | $2,202,678 |

| Oregon | 15% | 19% | 31% | 35% | $54,066 | 7.6% | 7.1% | $219,590 |

| Washington | 12% | 19% | 28% | 41% | $60,520 | 6.9% | 5.7% | $408,049 |

| United States | 15% | 19% | 30% | 36% | $52,047 | 7.2% | 5.9% | $16,701,415 |

| * Federal Poverty Level. "The U.S. Census Bureau's poverty threshold for a family with two adults and one child was $18,751 in 2013. This is the official measurement of poverty used by the Federal Government." † Median annual household income, 2011-2013. ‡ In millions of current dollars. "Gross State Product is a measurement of a state's output; it is the sum of value added from all industries in the state." Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "State Health Facts" | ||||||||

See also

- Energy policy in the U.S.

- Fracking in Hawaii

- Net metering

- Renewable Portfolio Standard

- Environmental policy in Hawaii

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Hawaii energy policy. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Hawaii State Energy Profile," May 19, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Chapter 3. Funding and Financial Incentive Policies," accessed March 1, 2017

- ↑ National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “State & Local Activities,” accessed January 30, 2014

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures, "State Renewable Portfolio Standards and Goals," accessed March 14, 2017

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Institute for Energy Research, "Hawaii Energy Facts," accessed March 15, 2017

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 DSIRE, "Hawaii - Renewable Portfolio Standard," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hawaii State Legislature, "Part V. Renewable Portfolio Standards," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hawaii State Legislature, "House Bill 623," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ U.S. Department of Energy, "GreenSun Hawaii," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ DSIRE, "Farm and Aquaculture Alternative Energy Loan - Hawaii," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ DSIRE, "Hawaii - Building Energy Code," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ Hawaii Department of Accounting and General Services, "Adoption of Chapter 3-181.1," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ DSIRE, "Hawaii - Renewables and Efficiency in State Facilities & Operations," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency, "Glossary," accessed October 22, 2014

- ↑ Edison Electric Institute, "Straight Talk About Net Metering," September 2013

- ↑ Call Me Power, "What is the difference between wholesale and retail electricity?" March 12, 2015

- ↑ DSIRE, "Net metering programs," accessed February 28, 2017

- ↑ GreenTechMedia, "Hawaii Regulators Shut Down HECO’s Net Metering Program," October 14, 2015

- ↑ DSIRE, "Hawaii - Net Metering," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "British Thermal Units (Btu)," December 15, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Table 13. Productive Capacity and Capacity Utilization of Underground Coal Mines by State and Mining Method, 2014," accessed July 19, 2016

- ↑ RWE, "How the electricity price is determined," accessed April 21, 2015

- ↑ Forbes, "How The Price For Power Is Set," December 26, 2012

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update," accessed April 25, 2016

- ↑ Tax Foundation, "How High Are Gas Taxes in Your State?" July 23, 2016

- ↑ The Washington Post, "A (very) brief history of the state gas tax on its 95th birthday," February 25, 2014

- ↑ American Petroleum Institute, "Motor Fuel Taxes," accessed April 27, 2016

- ↑ U.S. Department of Transportation, "When did the Federal Government begin collecting the gas tax?" November 18, 2015

- ↑ Business Dictionary, "Electric utility," accessed February 28, 2017

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 U.S. Department of Energy, "A Primer on Electric Utilities, Deregulation, and Restructuring of U.S. Energy Markets," May 2002

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Electric Choice, "Map of Deregulated Energy States and Markets (Updated 2017)," accessed February 28, 2017

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Allied Power Services, "Deregulated States," accessed February 28, 2017

- ↑ Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, "Introduction," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, "Energy," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ WhatIs.com, "North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC)," accessed February 28, 2017

- ↑ North American Electric Reliability Corporation, "Frequently asked questions," August 2013

- ↑ North American Electric Reliability Corporation, "Electricity Modernization Act of 2005," accessed March 15, 2017

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 U.S. Department of Energy, "How Much Energy Does Your State Produce?" November 10, 2014

- ↑ Academy Health, "Impact of the Economy on Health Care," August 2009

- ↑ The Conversation, "Budget explainer: What do key economic indicators tell us about the state of the economy?" May 6, 2015

- ↑ Health Affairs, "Socioeconomic Disparities In Health: Pathways And Policies," accessed July 13, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Distribution of Total Population by Federal Poverty Level," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Median Annual Household Income," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Unemployment Rate (Seasonally Adjusted)," accessed July 17, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Gross State Product (GSP) (millions of current dollars)," accessed July 17, 2015