What do you get when you combine a block party and a baseball league?

“Hey -- heads up, there’s a couple horses out in right field.”

Live in Austin, Tex., long enough, and you’re bound to hear the stories. About an architect who just wanted to keep playing baseball, so he got some friends together and built himself a field in his own backyard. About how you wouldn’t believe the beauty of the place, known as "The Long Time", out beyond the city limits and nestled among the trees and wildflowers and small family farms of central Texas.

About how that group of friends started playing what they called sandlot baseball, then found a few more friends, until soon enough it had grown a crowd: artists, musicians, men, women, filmmakers, photographers, dads, 20-somethings -- all gathered to sit in the sun, goof off, crack a beer (or some artisanal seltzer), listen to a band or two and maybe celebrate some dingers. About how they had so much fun that it couldn’t help but spread like wildfire, touching nearly every corner of the state and attracting everyone from Jack White to St. Vincent to Beto O’Rourke.

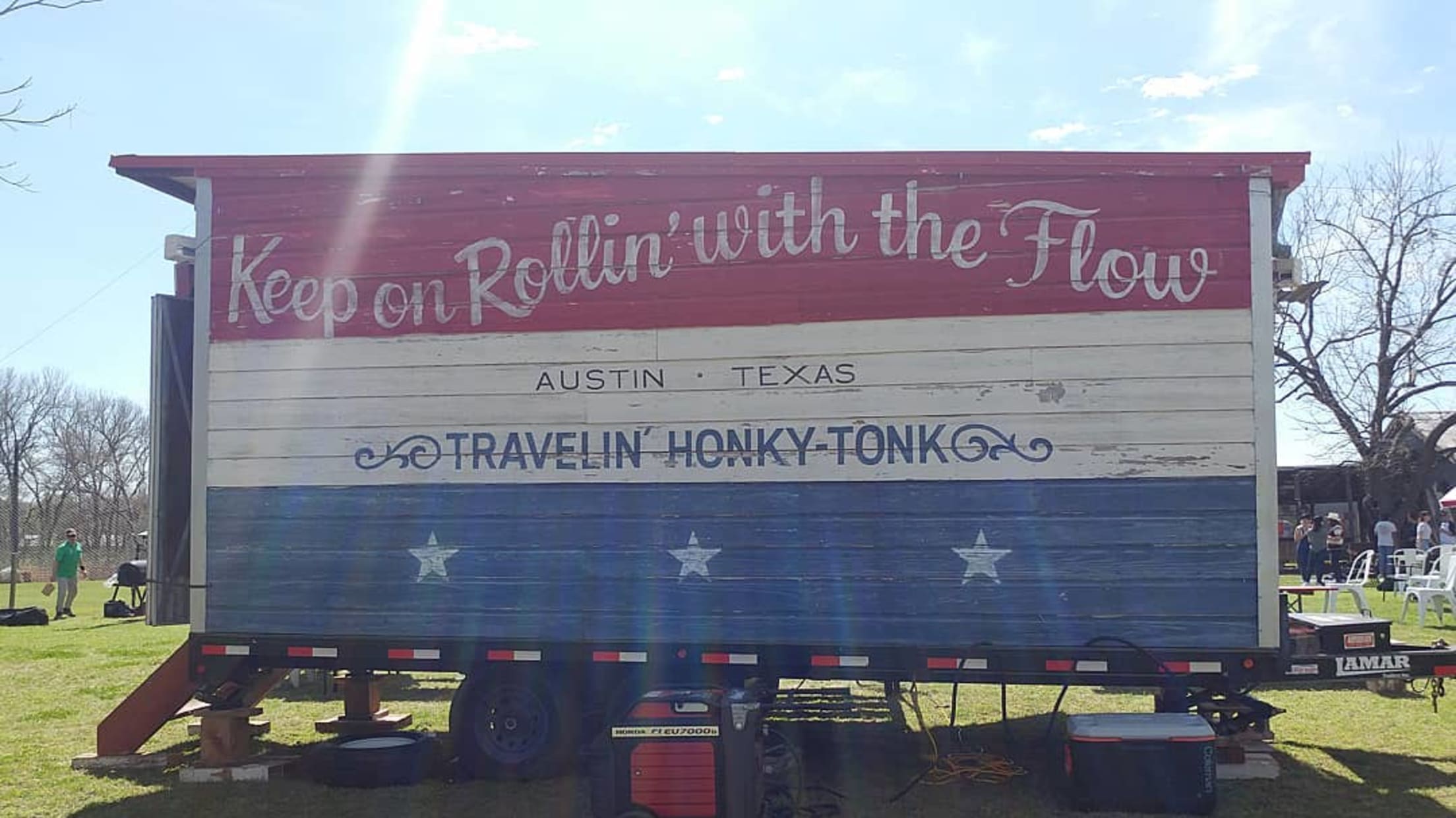

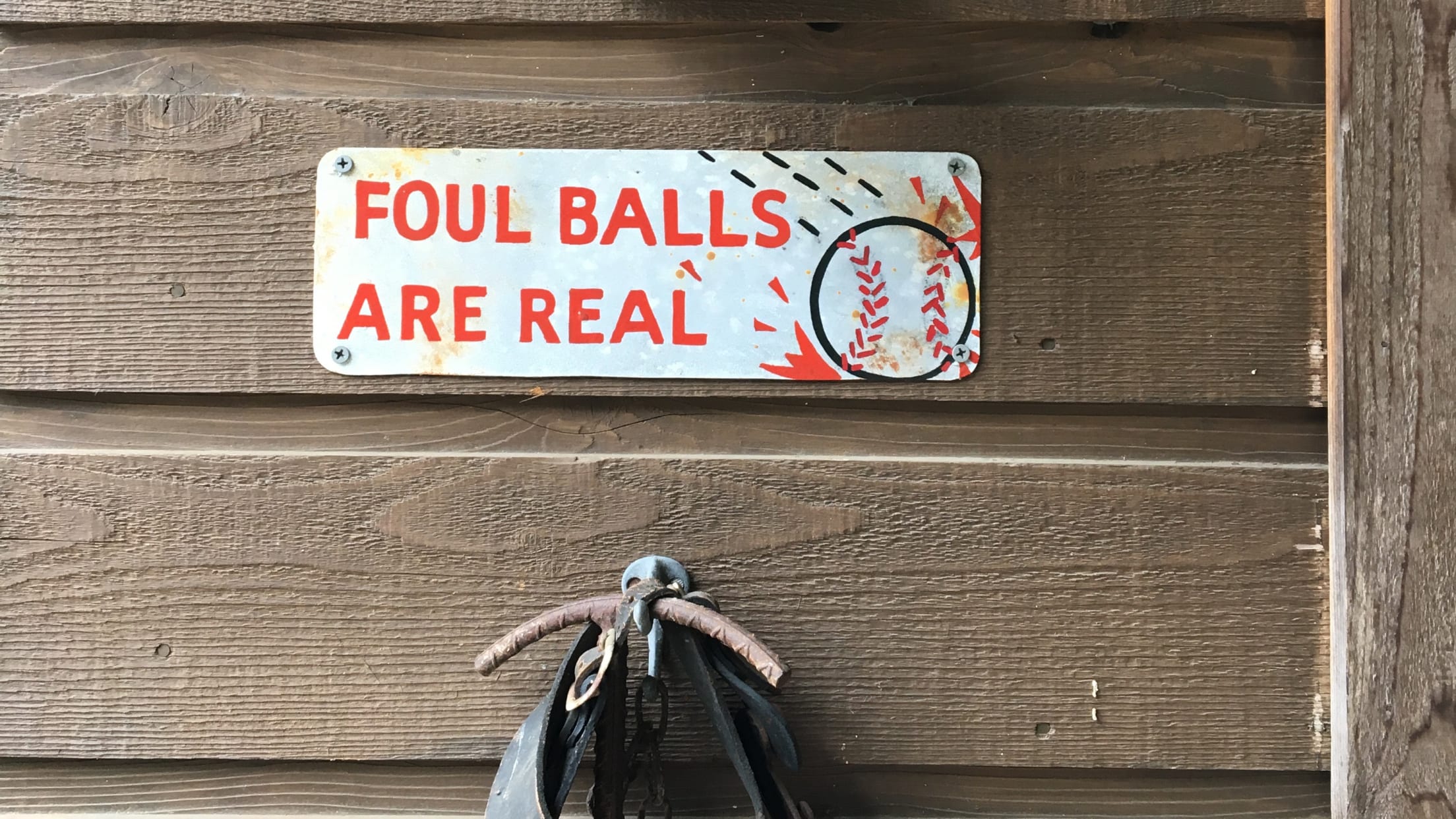

So you drive out one day for a doubleheader, the Austin Senators against the Houston Gamblers and the Texas Playboys against the Fort Worth Tee Balls, thinking you know roughly what to expect. You head east until you feel like you must’ve missed it, then turn down a small gravel driveway to the parking lot, where a man in overalls named Maxie zips by in a golf cart and points you to a patch of grass where you can park your car. You head in, past the people taking batting practice, past the sign warning you “FOUL BALLS ARE REAL,” past the flatbed trailer retrofitted into a stage, past the kids playing in the makeshift pool.

And then you find yourself back there a month later: The away team was down a couple guys, and one thing led to another, and someone asked if you were interested in playing -- that’s just the sort of thing that happens here -- and before long you’re No. 19 for the Mississippi Flood, borrowing a sweatband that reads “I like beer,” running out of the dugout that used to be a chicken coop while a man wearing an impossibly enormous belt buckle and a vintage Houston Gamblers football helmet is making what you assume to be a joke about the fact that you’re playing baseball on some sort of magical farm.

Then you get out there and turn around, and you realize that there are literally two horses in right field.

Sandlot baseball is tricky to define: Ask 10 participants, and they’ll all struggle to find the right words before inevitably giving you 10 different answers. It’s not really about the baseball. Sure, a game is played -- eight innings (nine seemed like a bit much, apparently), wood bats, 60 feet to home, 90 feet to first, a uniformed umpire who booms with the voice of God. But that game’s actual outcome could not be less of the point.

“It’s not really about watching the baseball,” a Gambler once explained from the dugout, before adding in a way both completely relaxed and utterly serious, “it’s about feeling the vibe.”

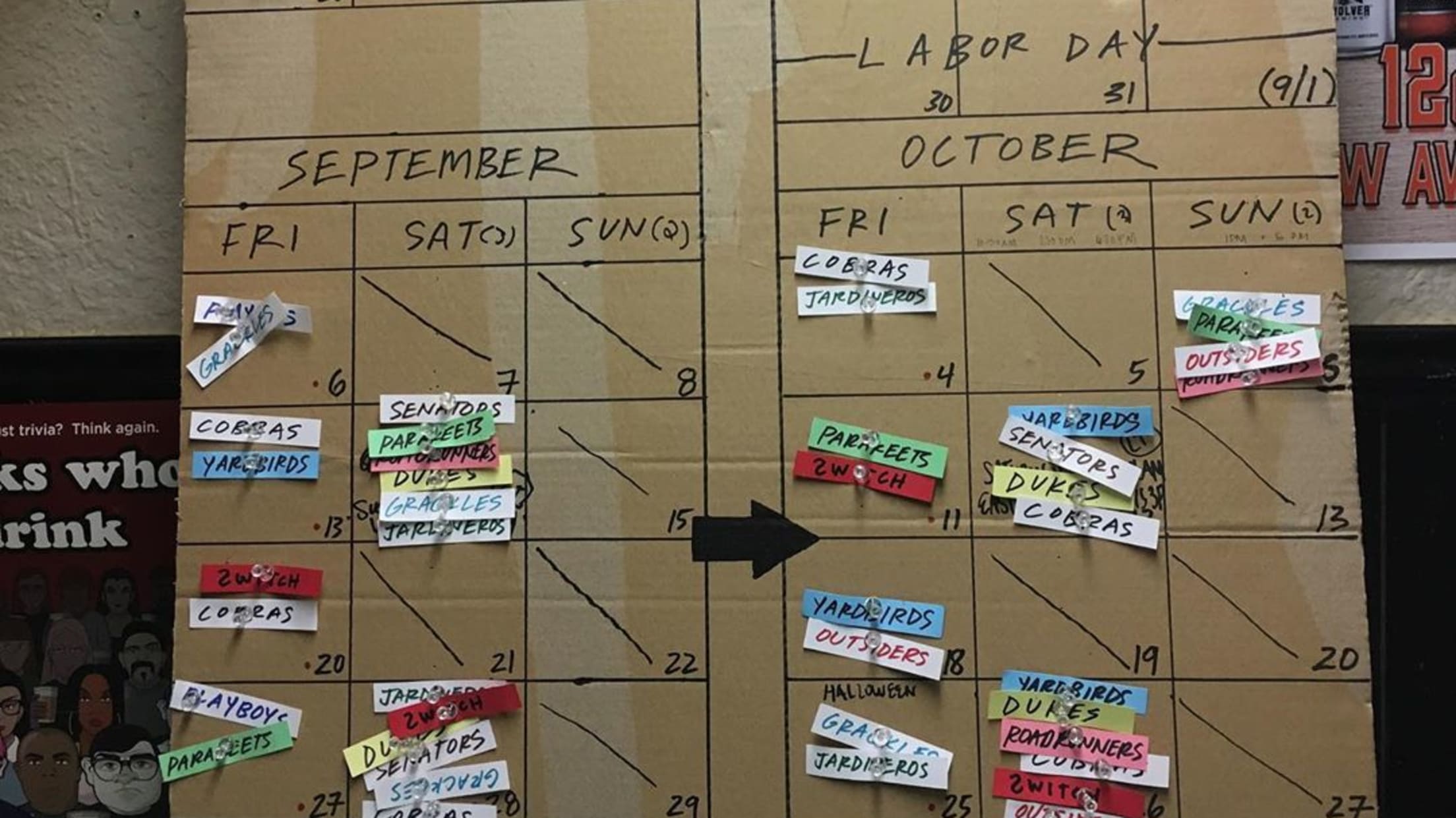

There are at least a dozen of these laid-back sandlot teams in Austin at this point, although that number seems to grow by the day. One Saturday a month, from March to October, four of them get together for a doubleheader at the Long Time -- a few hours of the strangest, warmest, most charming cookout you've ever seen in your life that just so happens to unfold in front of a diamond.

Minutes before my sandlot debut -- against the Cap City Cobras, another Austin Sandlot staple -- both teams are called to the middle of the Long Time diamond by Jack Sanders. Sanders is the master of ceremonies here, the founder of the Playboys and the man gracious enough to host us in his own personal playground. He embodies a very particular type of Texas masculinity: majestic beard, armadillo belt buckle, alarmingly easy drawl, his Stetson hat bobbing wherever he goes, the sort of guy you can’t help but find yourself drawn to. And he’s got some ground rules he wants to go over.

Rule No. 1: Plan your home runs carefully. Hit one, that’s great -- sandlot certainly isn’t opposed to the long ball. But they are opposed to showing anybody up, so if you hit one, you have to take your next at-bat from the opposite side of the plate.

Rule No. 2: Don’t be a hero. Sanders provides a helpful demonstration should you find that a ground ball or line drive is screaming toward you -- just take a step out of the way and wave to it on its way into the outfield.

Which brings us to the final and most important ground rule: Take it easy. This is sandlot’s foundation. Sanders frequently describes it as “the slow food of baseball,” and that pretty much sums it up. Nobody here is in a hurry; they all just want to run around in the sun and get up to some shenanigans. Lose sight of that -- start touching 85 mph on your fastball, for example -- and you’ll be gently reminded that this place is different. This isn’t the place to chase the bright lights of your glory days.

“We put a toe in the water of these men's city leagues, and it was just like kids throwing the ball too hard and just not having fun,” said Dave Mead, one of the founding members of the Playboys. “And we just thought, ‘Man, we want to play baseball, but winning is not everything. It's more about the experience, and it's more about the bond and the social engagement of it all. We just wanted to create something that we felt didn't exist.’”

This shouldn’t be misunderstood as apathy or laziness. There’s plenty that every sandlot team takes seriously, like designing and making their own (truly stellar) uniforms, or advertising each game with a beautiful custom poster, or inviting bands to stop by and play a set or two, or bringing in a food truck to ensure that you have access to a hot dog with andouille sausage and prickly pear relish.

But, crucially, the minute you step into the Long Time’s world, you become almost constitutionally incapable of taking the wrong things seriously: George Strait pours over the loudspeaker; there’s a spot beyond the third-base dugout that features a painting station, where a senior member of the Playboys will sit and work from time to time.

The first game I ever watched at the Long Time -- between the Senators and the Gamblers -- had to take a brief break between innings: It had been a while since anybody had thought to update the scoreboard above the bar/concession stand behind the first-base dugout, and no one had any idea what score it was.

So, for the next few minutes, both managers tried to improvise, asking every member of both teams -- and at one point even some of us sitting in lawn chairs behind the backstop -- whether they remembered having scored a run, and how many. Eventually (read: after everybody decided they didn’t care enough) they settled on numbers that felt right, and up the ladder they went.

I've had so, so much fun getting to hang out and watch some Texas sandlot baseball, and now I'm going to tweet out some video highlights. First up: the time no one could remember what the score was. pic.twitter.com/PaTX7jNdMu

— Chris Landers (@chrisoftheland) August 28, 2019

The second game that afternoon started off with a first pitch, but not as in “50 Cent nearly kills somebody in the first row”. Pitch as in pitching wedge. Fort Worth and the Playboys took turns trying to chip a ball onto a makeshift green that had been placed on the mound. Land it on the dirt, that was a run; hit the pin, that was three. This is the “Who’s Line Is It Anyway?” of baseball: Everything’s made-up, the points don’t matter and there are frequently props involved.

Next, the time they held a ceremonial first pitch -- like, with pitching wedges: pic.twitter.com/K9wrkOQ1zq

— Chris Landers (@chrisoftheland) August 28, 2019

That is why teams are more than happy to welcome anybody in, as evidenced by the fact that they happily let a washed up blogger who hadn’t swung a bat in a full decade suit up. At more than 50 members, the Playboys are just about at maximum capacity. But most others hold open practices, inviting you to drop in and out as your whims and schedule allow. No matter your gender, no matter your background, no matter your age -- the Playboys’ oldest member is a 57-year-old man named Nathaniel. If you can contribute to a good time being had, you’re in ... even if you’re not quite clear on what exactly baseball is.

The manager of the Flood told me about the last time they came down to Austin for a game, when they found themselves a player short and had to recruit a golfer onto the team at the last minute -- they turned teaching him the rules into a drinking game the night before, with, uh, limited results. Several sources confirmed that someone once started running the bases backwards, though reports varied as to which team they played for and just how far they got.

Seth Kessler, an original Cobra who’s now the team’s manager, has plenty of similar stories.

“One of our guys, he’s been on the team longer than anybody, and still does not grasp a lot of rules about the game of baseball,” Kessler says with a laugh. “We have to keep an eye on him -- his first game, he got on base, he's on first and he starts immediately taking his lead while the first baseman was still holding the ball."

The Long Time might be the epicenter of the movement, but sandlot baseball has sprouted up just about everywhere, a thousand different iterations from Texas to Pittsburgh to Oakland to Vancouver. There’s even a World Series, and a hashtag: the #SandlotRevolution. Some teams have costumes (Marfa once showed up to a game in prison outfits they’d borrowed from the local sheriff). Some have dance breaks. But each has its own origin story and its own distinct flavor, because each is so localized.

It’s not a coincidence that the proceeds from each Oklahoma City Cicadas poster go directly to the Curbside Chronicle, a magazine produced and sold by people experiencing homelessness in the city. Or that the Gamblers turn their games into food drives for the Houston food bank. Or that the first thing you see when you enter the Long Time is a thermometer gauging how far away the team is from its philanthropic goal (this year’s mark was set at $20,000). Every sandlot team is defined by a place, its people and the connections between them -- less a baseball game than a block party, united under the banner of “come on in, grab a drink and don’t be a dick”.

It’s a hell of a community, and it has one hell of a story. That story begins with Sanders.

More specifically, it begins in Hale County, Ala., where Sanders lived toward the end of his time studying architecture at Auburn University.

“Auburn has this program, it basically took students out of the classroom and put them in what they called the classroom of the community,” Sanders says. “We lived in the poorest small towns in Alabama and basically would integrate ourselves as best we could to meeting people and making friends. Those would then develop into architecture projects.”

It didn’t take long for Sanders to find his. It turned out that the little town of Newbern -- about an hour south of Tuscaloosa, population: 172 -- had its own baseball team: the Newbern Tigers, although locals simply called it “the baseball club”. It had been around for generations, both a means of entertainment on Sunday afternoons and a pillar of the community. When someone passed away, the club would dig a grave by hand and ensure that there were flowers at the funeral.

While other students headed back to Auburn on weekends, he stayed to hang out at the diamond.

“All these dudes that had tough jobs during the week and tough lives and not a lot of money and they just made the most out of their four at-bats and their game,” Sanders says. “And they laughed about their mistakes, and then they moved on. There was so much more serious things to worry about, this opportunity to play this game for three hours on a Sunday, you damn sure aren't going to take a strikeout home with you.”

Sanders soon found himself a part of that community: He always kept a glove in his trunk, and when an opponent showed up with only eight players, he hopped in and picked up a couple hits. Eventually, he became a full-on member of the Tigers. He decided that his final project at Auburn would be to design and build the team a backstop; it was completed in 2001.

Sanders left Newburn not long after, moving to Austin to enroll in graduate school at the University of Texas. But he made the Tigers a promise before he did: He would found his own team in his new home, and someday they would come back to Hale County and play some ball.

Unsurprisingly, he stuck to his word. Somewhat surprisingly, he did it with a little help from filmmaker Richard Linklater. The director grew up outside Houston, moved to Austin after college and never left -- and he just so happens to be a massive baseball fan. One of Sanders’ professors, Steve Ross, heard that Linklater wanted to build a treehouse on his property. Ross and Sanders went out for a visit, and before long the three were talking about the dream of bringing sandlot ball to Austin.

“I knew what an awesome opportunity to come to Austin, Tex., and tell one of its most awesome directors and storytellers this baseball story that I had,” Sanders says. “And he basically was like, ‘I'd love to see that. So why don't we just put a team together?’”

And thus, the Playboys were born. Ross came up with the name -- inspired by swing icon Bob Wills, who used to tour the state with his Texas Playboys in spectacular matching outfits:

Sanders rounded up some friends, mostly fellow creative types he knew from school, and in the summer of 2006 the Playboys embarked on their first road trip -- back to Newbern. They weren’t good, exactly: Sanders estimates the final score of that first game at something like 17-0. But they’d put together a baseball team, they’d gotten in some outfield yoga (a pregame tradition that continues to this day) and they’d looked damn good doing it.

They’ve kept on doing it for some 14 years now. That trip to Newbern was the first of what became annual road trips: to Florence, Ala., where the designer Billy Reid threw a party for them in the alley behind his flagship store; to Oxford, Miss., where they met in the town square for a quick stretch, then rented a full double-decker bus to drive them to the field; to Todos Santos, Mexico, where some friends hooked them up with a team to play … after spending the day prior fixing up a stadium that had been damaged by a recent hurricane.

Now, each February, all of the 50+ members of the Playboys meet for a banquet at Scholz’s, a beer garden downtown. It’s a black tie affair, where the group hands out awards, celebrates a year’s worth of highlights and puts together a PowerPoint presentation on where they should go next.

It was easy to barnstorm around the country, but playing locally in Austin was more difficult. The Playboys had trouble finding teams that matched the blend of competition and camaraderie they were looking for, so they simply scrimmaged against themselves. Soon enough, though, they discovered that they weren’t alone. They had a couple fellow travelers in their own backyard: The East Austin Jardineros -- “gardener” in Spanish, so named because most of the original team worked in landscaping -- and the Cap City Cobras, who named themselves after a snake that escaped from a pet store employee in a Lowe’s parking lot back in 2015 and instantly became a meme.

Anyone want to go check out Barton Springs tomorrow? I heard its a cool place to check out in town

— Austin Cobra (@Austin_Cobra) July 16, 2015

just finished my sweep of @Lowes. All clear. Also - nice sale on patio furniture.

— Austin Mongoose (@austin_mongoose) July 16, 2015

The Jardineros and Cobras had similar stories: They loved baseball growing up, but at a certain point -- in tee ball, in Little League, in high school, in college -- the game became more serious than fun. They’d drifted away from it, and now they just wanted to get back to feeling like little kids again.

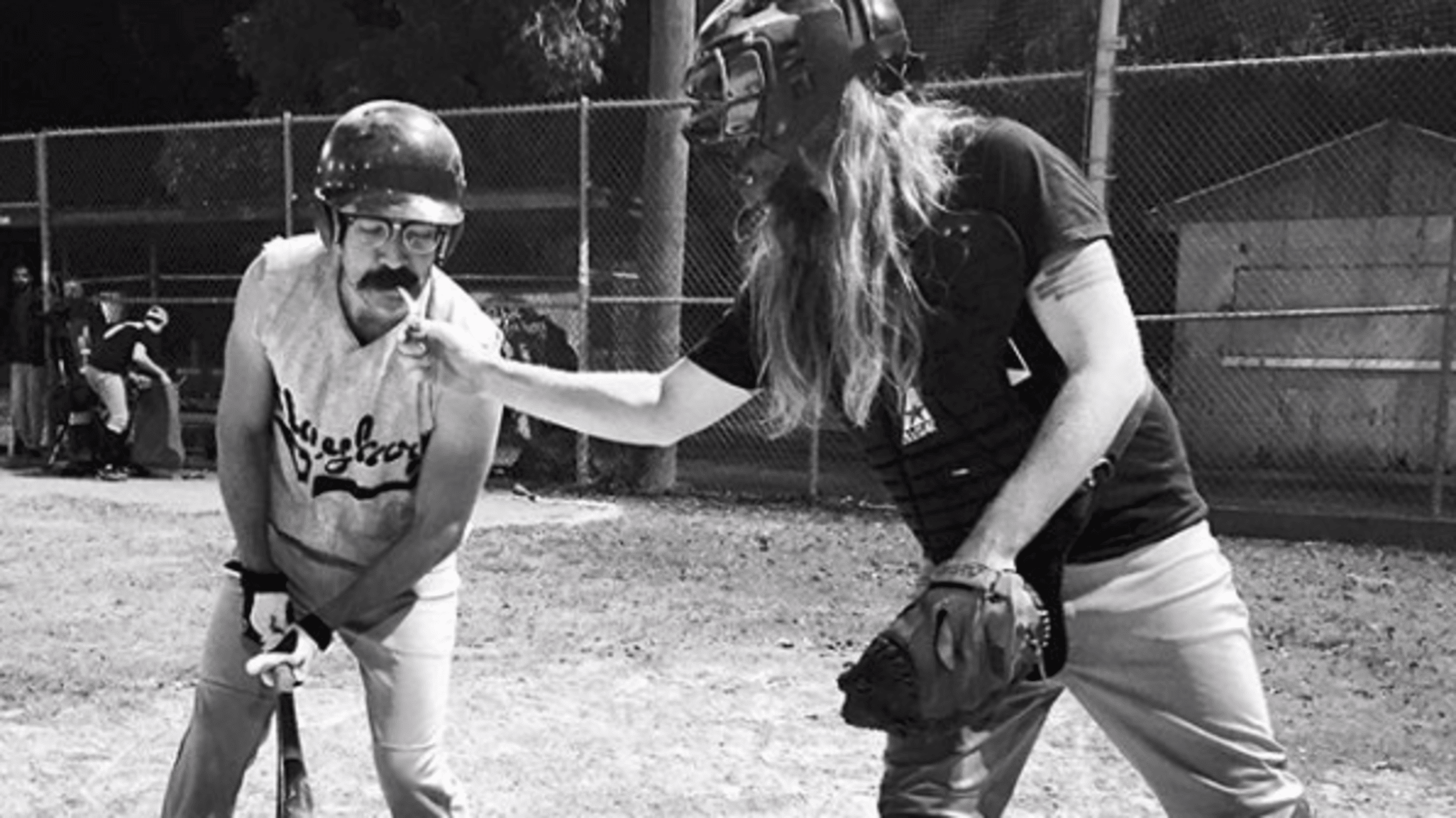

“Our founder, Will, he got pretty drunk on whiskey watching Ken Burns -- he got a little weepy at it like we all do,” Kessler, the Cobras’ manager, says. “Next day he went out, texted everybody in his phone, bought some shitty catcher's gear, baseball bats and a half-dozen baseballs and said ‘I'll be at this field at this time.’”

The early days of the Cobras were, uh, unconventional: a handful of guys in jean shorts and chain wallets with varying ideas about how exactly baseball worked. There’s Grace, the woman who shows up to every game on a Harley and works as a petsitter. There was Ray Ray, the professional boxer who billed himself as the best pitcher on the team despite barely being able to reach home plate from the mound. There was Benny Boy, the catcher who would only play in a Speedo and a glove he’d spray-painted gold. There was Trevor Fox, the shortstop who lived in a van and showed up every now and then with highlights in his hair and nothing but sliding shorts on -- until one day he bailed, explaining that he had to go visit his parents before he left for medical school.

“I'm like, ‘Wait, you're going to school?’” Kessler says. “He was like, ‘Yeah, I got accepted to Johns Hopkins medical school, I'll see you later.’ That was the last time I ever saw him.”

And then, of course, there were the knives.

“Who was the guy who always played with a knife on his belt?”

“Oh, yeah. He's like sliding into the base, I was like ‘What are you doing? That could go wrong very easily.’”

“There were a lot more weapons on the field in the early years.”

“I miss when random blades were found on the basepaths -- oh whose knife?”

Possible manslaughter aside, the Cobras understood that the “being good at baseball” part wasn’t nearly as important as the “friends drinking in a field” part. They started playing the Playboys and Jardineros in a park in East Austin on Friday nights. The story of Friday Night Lights soon spread, and people started showing up. More and more people.

After a while, the crowds got to be so much that Sanders started to think bigger. So he did what an architect does: He retrofitted his own property into a field of dreams. That’s a groaning cliche, but it’s hard to find another word to describe it: the hay bales lining the left-field fence, the bar slinging hot dogs built out of the back of the backstop, the landline nailed to a dugout wall that reads, simply and ominously, “I’M NOT HERE”. There’s something about the place that makes you feel like you can’t be touched, that the anxieties you came with are a fraction less important than they were a few minutes ago, that you’re among friends even if you don’t know a single soul there.

What had started as a goof had turned into a getaway. Mead described it perfectly: “A Saturday afternoon sort of jaunt to the country for a gathering of friends and food and beer and live music, and then there just happens to also be a fast pitch baseball game happening on the other side of the fence that some people may be paying attention to and some people aren't."

Anybody who was anybody had to make the pilgrimage. I asked Mead for his favorite memory from a decade-plus as a Playboy; his voice lowered a bit, the way it does when you’re really trying to avoid the impression that you’re humble-bragging, before offering two. First, the time he got booed off the field after (unintentionally!) striking out Beto O’Rourke when the then-Senate candidate stopped by to play a few innings with Los Diablitos de El Paso while campaigning in 2018.

Second, the time he got viciously trolled by Jack White after the rock star -- and first baseman for the Warstic Woodmen -- tagged him out to end the game.

“He applied the tag, and we got tangled up and both fell down. No hesitation, he stood up, slammed his glove on the ground right next to my face and ran off in celebration.”

Once people got a taste of it, it was hard not to be hooked. New teams pop up all over town, advertising open practices and a good time. Befitting a scene as open as this one, they come in all shapes and sizes: there are the Senators, the Grackles, the Yardbirds, the Dukes. Representatives from each get together at a pub on the east side at the beginning of each year and go about the very serious work of putting together a schedule -- teams jockey for specific dates and opponents until everybody’s (mostly) satisfied.

The squad most in demand? The Austin Switch -- which is fitting, because they’re probably the best embodiment of the sandlot ethos. They don’t bother identifying as a specifically LGBTQ club, but that’s mostly because they want to take everyone as they are; the team’s “about 60/40 gay/straight,” according to one of its founders, Breezy Purcell. Purcell got into sandlot through the Playboys’ b-team, and loved it so much that she eventually got together with Braden Williams -- a legend in Austin’s gay softball community -- to found a team of their own.

“People had like Kirk Cameron and New Kids on the Block on the wall and I had Ozzie Smith,” said Purcell, who grew up a Cardinals fan in Illinois. “Baseball is to me as much of my life as a lot of things have been, including being queer.”

Whereas most of the original sandlot teams grew out from a group of friends, the Switch has been far more inclusive from the jump. Its crowd is truly all over the place -- with all sorts of fans.

“I did ask my buddy Clarence, who's a drag queen, to come do cards like a boxing match in between in the seventh inning,” Williams says.

The Long Time has become the epicenter of a whole wonderfully weird universe. It stretches far and wide: The Gamblers began after Reagan Kneese, the guy in the helmet, read about the Playboys in Garden and Gun magazine and wanted a team of his own -- only to discover that Sanders was a friend’s brother-in-law. He brought some friends to an early Gamblers game, and they too decided that they wanted in, which marked the founding of the Houston Buffs.

Sandlot’s even made it all the way out to Marfa -- a town that’s half one-stoplight outpost, half famed artist getaway, flung out in the West Texas wilderness maybe an hour north of the border. Every year, they’d face off against the Playboys at the Trans-Pecos music festival. That's how St. Vincent wound up at a ball field in the desert singing the national anthem (it starts around the 1:55 mark):

Marfa’s remoteness presents what I’ll gently refer to as logistical issues -- gophers and groundhogs have been known to turn the outfield into a minefield. But they make it work, and most importantly, they know how to have a good time. Who knows, you might even see a pregame dance-off featuring a chicken mascot for some reason:

And finally, all the way from Marfa, a dance party featuring a weird chicken mascot: pic.twitter.com/kMgvpBAVsA

— Chris Landers (@chrisoftheland) August 28, 2019

That’s a long way away from where it started, a group of friends making something out of nothing in a park in front of no one in particular.

And yet, somehow, it still works. Sanders still gets out there on the mound, Stetson hat, bum shoulder and all, although in his older age he relies more on an eephus pitch he’s dubbed Purple Rain. Games still get interrupted to sing a quick happy birthday to one of the players. They’re still the same guys who welcome New Orleans to town with a righteous sax rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner.

Through it all, the vibe remains. You get the sense that nobody wants to be the one who messes it up -- that no matter how big it gets, no matter how large the crowds, everyone is invested in preserving this as a space in which you can bring your weirdness, whatever it is, and lay it out in the sun for everyone to see.

“People don't know that it's really just not that hard,” Sanders says of this thing he's helped create. “They just look at this sport and they’re like, 'nothing', it's not even an option for them. And then they end up on a blanket at the Long Time eating Cracker Jacks for nine dollars, and they realize that they can actually -- [they're] people that didn't even know they liked baseball or that they were invited.”