After much speculation, it’s official: MLB will be going to a “bubble” format for most of its postseason, isolating players and staff at a handful of locations to try to avoid any Covid outbreaks like the ones that disrupted many teams’ regular seasons. After the first round of best-of-three series takes place at teams’ regular home parks, the National League Division Series will be held at Arlington and Houston and American League Division Series will be in San Diego and Los Angeles, followed by League Championship Series in Arlington and San Diego, then a World Series in Arlington.

Going to a bubble makes sense: It’s worked well for the NBA and NHL, and does seem to be the best way to prevent outbreaks. And baseball has even thought through some of the problems of starting a bubble on the fly — players will have to start self-quarantining at their homes and hotels as early as next Tuesday, with their families joining them then in quarantine if they want to enter the bubble with them, though given that players are already not supposed to be out on the town, this pretty much comes down to “try extra-hard not to get sick right before the playoffs, guys.”

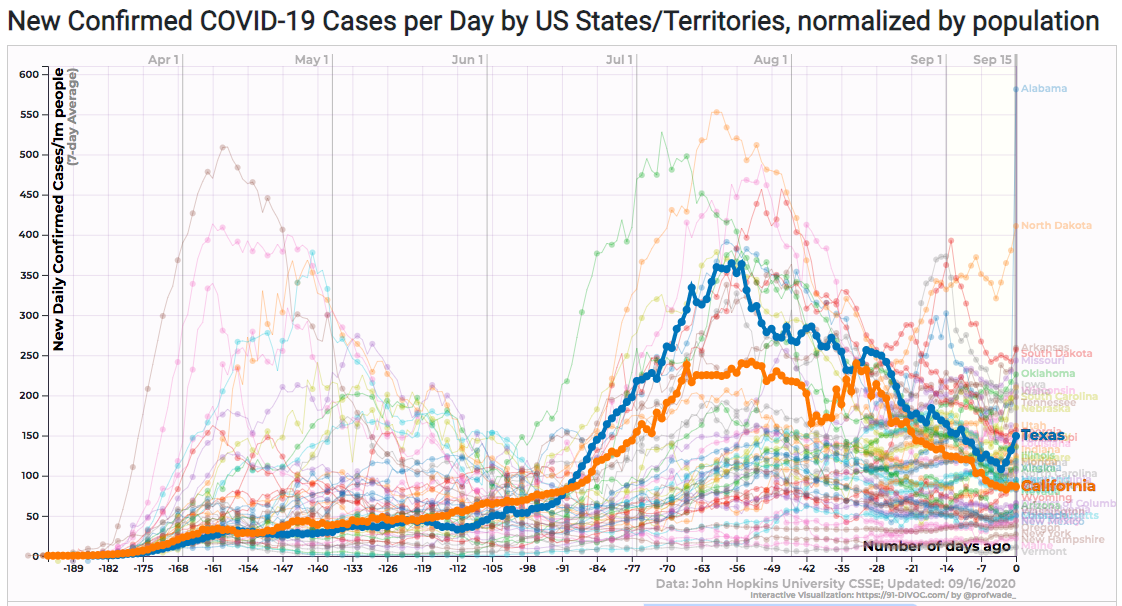

Playing in Southern California and Texas is more puzzling, though. Sure, they’re both warm-weather sites, though pretty much all of North America is relatively warm in October now thanks to climate change, except when it’s not. But they’re also both relatively high-virus states: Texas has begun to see a major second spike after its huge outbreak that began in June, and California isn’t far behind.

(That’s one-week new-case averages, but if you check 91-DIVOC you can see similar trends underway for positivity rates, so this isn’t just a matter of more people getting tested — there really is way more virus afoot in Texas and California than in states like New York and Massachusetts. And while a bubble in high-virus Florida worked okay for the NBA, it also didn’t have players traveling between cities.)

On top of that, warm weather hasn’t exactly been good for California lately, given that Los Angeles County just saw a record high temperature of 121 degrees and, oh yeah, the whole damn state is on fire. Maybe the wildfires will have died down by October, but wildfire season in Southern California usually lasts till the start of November, and thanks again to climate change is basically all year round now, so baseball could be risking a repeat of this week’s games in Seattle that had to be canceled after the Oakland A’s and Seattle Mariners played a doubleheader in a cloud of choking smoke.

The first thing that comes to mind is MLB’s longstanding tradition of rewarding team owners who’ve built or renovated stadiums with getting to host special events like the All-Star Game. The Texas Rangers‘ stadium, of course, only just opened this year, after winning close to half a billion dollars in city subsidies so they could have air-conditioning, while Dodger Stadium just got a $100 million renovation (at team expense), and in fact was in line to host the All-Star Game this summer before that got canceled. And once you’ve picked those two, the Houston Astros and San Diego Padres stadiums are relatively close to reduce travel, and also relatively new, though, man, Houston’s is 20 years old already? I guess Enron was a long time ago.

Texas has another advantage, though. MLB commissioner Rob Manfred had this to say yesterday at a sports business panel:

“I’m hopeful that [for] the World Series and the LCS we will have limited fan capacity,” Manfred said during a question-and-answer session through Hofstra’s Frank G. Zarb School of Business. Manfred’s comments were first reported by the Athletic. “I think it’s important for us to start back down [that] road. Obviously, it’ll be limited numbers, socially distanced, [with] protection provided for the fans in terms of temperature checks and the likes…

“But I do think it’s important as we look forward to 2021 to get back to the idea that live sports are safe. They’re generally outdoors, at least our games, and it’s something we can get back to.”

Whether live outdoor sports are safe for fans to attend in the middle of a pandemic outbreak is, of course, a huge open question, one that the NFL is currently attempting to answer via a giant human test subject experiment. Also, the Houston and Texas stadiums aren’t entirely outdoors — they both have retractable roofs, and in fact the roof is the entire reason for the Texas stadium existing — and while they probably still have better air circulation than a totally indoor arena, if the principle here is “it’s safe to let in fans so long as its outdoors,” shouldn’t Manfred have picked entirely outdoor stadiums? Hell, New York City has two of ’em, plus oodles of now-vacant hotel rooms.

Ah, but New York City also has bans on fans attending live sporting events, and Texas notably does not. And even at 25% capacity, selling tickets for the World Series — the only tickets that would be available for any MLB games this year — would be massively hot commodities, something that Manfred said later in his talk was at the forefront of baseball’s thoughts:

“The owners have made a massive economic investment in getting the game back on the field [in 2020] for the good of the game,” he said. “We need to be back in a situation where we can have fans in ballparks in order to sustain our business. It’s really that simple.”

So, yeah, it really is that simple: If we can sell tickets, that’s the priority, we’ll figure out the risks later.

Prioritizing money over safety also explains perhaps the biggest hole in the MLB bubble structure: The first-round games, which will be held in eight different cities, with no bubbles, right before the embubbled postseason begins. This Round of 16 was announced abruptly at the beginning of the season, and doesn’t make any more baseball sense than public health sense — three-game series in baseball have essentially random outcomes, especially now that home-field advantage maybe means nothing without fans (though maybe it still does?), so you’re subjecting regular-season division winners to virtually the same odds of making it to the next round as sub-.500 teams lucky enough to play in weak divisions. But it does mean a whole lot more TV money, enough that MLB was willing to cough up $393 million in postseason bonus money to the players’ union to make it happen.

And as Marc Normandin points out in today’s edition of his newsletter (this one un-paywalled, but please send him some money if you like it!), even before seeing whether this results in a bunch of third-place teams on hot streaks battling it out in the playoffs, Manfred is already eager to make this the new normal:

“Manfred also said the expanded, 16-team postseason is likely to remain beyond 2020, adding that “an overwhelming majority” of owners had already endorsed the concept before the pandemic.

“I think there’s a lot to commend it,” he said, “and it is one of those changes I hope will become a permanent part of our landscape.”

Normandin also points out that letting a thousand playoff teams bloom has an important side benefit for team owners who are sick of shelling out big bucks to buy the best team possible:

If the league was already full of teams aiming to win 83 games because it’s cheaper than trying to win 90 and they might get lucky and win 90, anyway, what is going to happen when the threshold for making the postseason drops? A bunch of teams looking to win 75 games and occasionally being rewarded for it because a prospect hits their stride sooner than expected, or an inexpensive, low-end free agent has a surprise epiphany and subsequent breakout? We’re going to end up in a scenario where owners know they’ll be getting increased shared revenue from an expanded postseason, and more revenue than that if their teams manage to make it there themselves. And little incentive to spend any of that increased revenue, because why try when not trying might get you to the postseason, anyway?

In other words, if you loved the marginal revenue gap that has allowed owners to pocket even more money without having to collude about it, it’s about to get that much bigger.

MLB’s bubble postseason, in short, is one part profiteering and one part just enough concern for the public to seem reasonable without getting in the way of the profiteering. Which is how baseball — and pretty much all pro sports in the U.S. — has always been run, so it should come as no surprise. But it’ll be something to keep in mind while watching the Toronto Blue Jays and San Francisco Giants battle it out for the World Series in Texas in front of 12,500 very well-heeled and well-air-conditioned fans.