International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a space station, a very large satellite that people can live in for several months at a time. It was put together in Low Earth orbit up until 2011, but other bits have been added since then. The last part, a Bigelow module was added in 2016. The station is a joint project among several areas of the world: the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, and Canada. Other nations such as Brazil, Italy, and China also work with the ISS through cooperation with other countries.

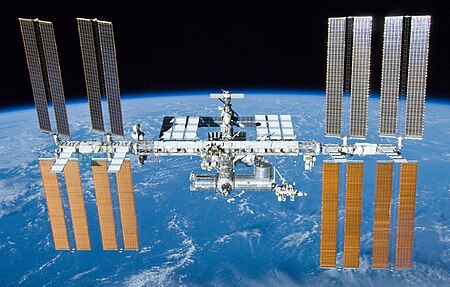

ISS of STS-132 | |

| |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1998-067A |

| SATCAT no. | 25544 |

| Call sign | Alpha, Station |

| Crew | Fully crewed: 3-6 Currently aboard: 7 (Expedition68) |

| Launch | 20 November 1998 |

| Launch pad | |

| Mass | ≈ 419,725 kg (925,335 lb)[1] |

| Length | 72.8 m (239 ft) |

| Width | 108.5 m (356 ft) |

| Height | ≈ 20 m (66 ft) nadir–zenith, arrays forward–aft (27 November 2009)[needs update] |

| Pressurised volume | 931.57 m3 (32,898 cu ft)[2] (28 May 2016) |

| Atmospheric pressure | 101.3 kPa (29.9 inHg; 1.0 atm) |

| Perigee | 408 km (253.5 mi) AMSL[3] |

| Apogee | 410 km (254.8 mi) AMSL[3] |

| Orbital inclination | 51.64°[3] |

| Orbital speed | 7.66 km/s[3] (27,600 km/h; 17,100 mph) |

| Orbital period | 92.68 minutes[3] |

| Orbits per day | 15.54[3] |

| Orbit epoch | 14 May 2019 13:09:29 UTC[3] |

| Days in orbit | 26 years, 14 days (5 December 2024) |

| Days occupied | 24 years, 1 month, 2 days (5 December 2024) |

| No. of orbits | 116,178 as of May 2019[update][3] |

| Orbital decay | 2 km/month |

| Statistics as of 9 March 2011 (unless noted otherwise) References: [1][3][4][5][6] | |

| Configuration | |

| |

Building the ISS began in 1998, when Russian and American space modules were joined together.

Origin

changeIn the early 1980s, NASA planned Space Station Freedom as a counterpart to the Soviet Salyut and Mir space stations. It never left the drawing board and, with the end of the Soviet Union and the Cold War, it was cancelled. The end of the Space Race prompted the U.S. administration officials to start negotiations with international partners Europe, Russia, Japan and Canada in the early 1990s in order to build a truly international space station. This project was first announced in 1993 and was called Space Station Alpha.[7] It was planned to combine the proposed space stations of all participating space agencies: NASA's Space Station Freedom, Russia's Mir-2 (the successor to the Mir Space Station, the core of which is now Zvezda) and ESA's Columbus that was planned to be a stand-alone spacelab.

Manufacturing

changeThe ISS components was manufactured in various factories all over the world, and were all shipped into the Space Station Processing Facility at Kennedy Space Center for last stages of manufacturing, machine assembly and launch processing. The components are made from stainless steel, titanium, aluminum and copper.

Assembly

changeThe assembly of the International Space Station is a great event in space architecture.[4] Russian modules launched and docked by their rockets. All other pieces were delivered by the Space Shuttle. The Bigelow Module was delivered with a Falcon 9. As of 5 June 2011[update], they had added 159 components during more than 1,000 hours of EVA.[8] Many of the modules that launched on the Space Shuttle were tested on the ground at the Space Station Processing Facility to find and correct problems before launch.

The first section, the Zarya Functional Cargo Block, was put in orbit in November 1998 on a Russian Proton rocket. Two further pieces (the Unity Module and Zvezda service module) were added before the first crew, Expedition 1, was sent. Expedition 1 docked to the ISS on 1 November 2000, and consisted of U.S. astronaut William Shepherd and two Russian cosmonauts, Yuri Gidzenko and Sergey Krikalev. Since then, it has continuously been home to astronauts and cosmonauts to the present day.

Life in space

changeBedtime

changePeople living in the space station have to get used to all kinds of changes from life on Earth. It takes them only 90 minutes to orbit (go around) the earth, so the sun looks as if it is rising and setting 16 times a day. This can be confusing, especially when one is trying to decide when they should go to bed. The astronauts try to keep a 24-hour-schedule anyway. At bedtime, they have to sleep in sleeping bags that are stuck to the wall. They have to strap themselves inside so they will not float away while sleeping.[24] En:wikt:Strap

Zero gravity

changeIn orbit there is no G-Force (this is called free fall or zero gravity). To help prepare astronauts experience zero gravity, NASA trainers put the astronauts in water. Because water makes one float, this is a little like experiencing no gravity. However, in water they can push against the water and move around. In zero gravity, there is nothing to push against, so they just float in the air. Another way of training is going in a plane and making the plane fall to earth very quickly. This lets people experience zero gravity for a very short time. This training can make people quite sick at first. Astronauts feel as if there is no force acting on them.

In zero gravity, the astronauts do not use their legs very much, so they need to get lots of exercise to keep them from becoming too weak. Without gravity, astronauts can get big upper bodies and skinny legs. This is called chicken-leg syndrome. Astronauts must exercise hard, every day, to remain healthy.

Eating in space style is difficult. Water and other liquids do not flow down in space, so if any were spilled in the space station, it would float around everywhere. Liquids can ruin electronic equipment, so astronauts have to be very careful in space. They drink by sucking water out of a bag, or from a tube stuck to the wall. They cannot put their food on plates because it would just float right off, so they put it in pouches and eat from the pouches. The food they eat is usually dried, because any crumbs can ruin the equipment.

Sometimes fresh fruits and vegetables are sent up to the astronauts, but it is very expensive and hard to send it, so they have to bring plenty of food with them.[24]

Bathroom

changeIn space, the bathroom should probably be called the restroom instead, because one really can not take baths there. Instead, astronauts use squirt guns to take a shower. One person squirts himself with a gun while other people stand outside with a water vacuum to get rid of all the water that floats out of the shower. This is quite hard, so astronauts usually just take a "sponge bath" with a wet cloth.

Toilets can be another problem. Toilets are supposed to use gravity to work. When one flushes a toilet, gravity makes the water go down. Since the astronauts on the ISS do not feel any gravity, the toilet must be attached to the astronauts and gently suck away all their waste.[24]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Garcia, Mark (9 May 2018). "About the Space Station: Facts and Figures". NASA. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Space to Ground: Friending the ISS: 06/03/2016". YouTube.com. NASA. 3 June 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Peat, Chris (28 September 2018). "ISS – Orbit". Heavens-Above. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 NASA (18 February 2010). "On-Orbit Elements" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "STS-132 Press Kit". NASA. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "STS-133 FD 04 Execute Package". NASA. 27 February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ GAO (June 1994). "Space Station: Impact of the Expanded Russian Role on Funding and Research" (PDF). GAO. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- ↑ "The ISS to Date". NASA. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Wade, Mark (15 July 2008). "ISS Zarya". Encyclopaedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ "Unity Connecting Module: Cornerstone for a Home in Orbit" (PDF). NASA. January 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ "Zvezda Service Module". NASA. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ "US Destiny Laboratory". NASA. 26 March 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ↑ "Space Station Extravehicular Activity". NASA. 4 April 2004. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ "Space Station Assembly: Integrated Truss Structure". NASA. Archived from the original on 7 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ "P3 and P4 to expand station capabilities, providing a third and fourth solar array" (PDF). Boeing. July 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ "STS-118 MISSION OVERVIEW: BUILD THE STATION…BUILD THE FUTURE" (PDF). NASA PAO. July 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ "Columbus laboratory". ESA. 10 January 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ↑ "About Kibo". JAXA. 25 September 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ↑ "Kibo Japanese Experiment Module". NASA. 23 November 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly. "Docking Compartment-1 and 2". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (9 November 2009). "Russian module launches via Soyuz for Thursday ISS docking". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "NASA Extends Contract With Russia's Federal Space Agency" (Press release). NASA. 9 April 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ "NASA to Test Bigelow Expandable Module on Space Station". NASA. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Living and Working on the International Space Station" (PDF). CSA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

Other websites

change- International Space Station -Citizendium