We talk about Morse code, named after its inventor, Samuel Morse. However, maybe we should call it Vail code after Alfred Vail, who may be its real inventor. Haven’t heard of him? You aren’t alone. Yet he was behind the first telegraph key and improved other parts of the fledgling telegraph system.

The story starts in 1837 when Vail visited his old school, New York University, and attended one of Morse’s early telegraph experiments. His family owned Speedwell Ironworks, and he was an experienced machinist. Sensing an opportunity, he arranged with Morse to take a 25% interest in the technology, and in return, Vail would produce the necessary devices at the Ironworks. Vail split his interest with his brother George.

By 1838, a two-mile cable carried a signal from the Speedwell Ironworks. Morse and Vail demonstrated the system to President Van Buren and members of Congress. In 1844, Congress awarded Morse $30,000 to build a line from Washington to Baltimore. That was the same year Morse sent the famous message “What Hath God Wrought?” Who received and responded to that message? Alfred Vail.

The Original Telegraph

Telegraphs were first proposed in the late 1700s, using 26 wires, one for each letter of the alphabet. Later improvements by Wheatstone and Cooke reduced the number of wires to five, but that still wasn’t very practical.

Samuel Morse, an artist by trade, was convinced he could reduce the number of wires to one. By 1832, he had a crude prototype using a homemade battery and a relatively weak Sturgeon electromagnet.

Morse’s original plan for code was based on how semaphore systems worked. Messages would appear in a dictionary, and each message would be assigned a number. The telegraph produced an inked line on a paper strip like a ticker tape. By counting the dips in the line, you could reconstruct the digits and then look up the message in the dictionary.

Morse’s partners, Vail and a professor named Gale, didn’t get their names on the patents, and for the most part, the partners didn’t take any credit — Vail’s contract with Morse did specify that Vail’s work would benefit Morse. However, there is evidence that Vail came up with the dot/dash system and did much of the work of converting the hodgepodge prototype into a reliable and manufacturable system.

Improvements

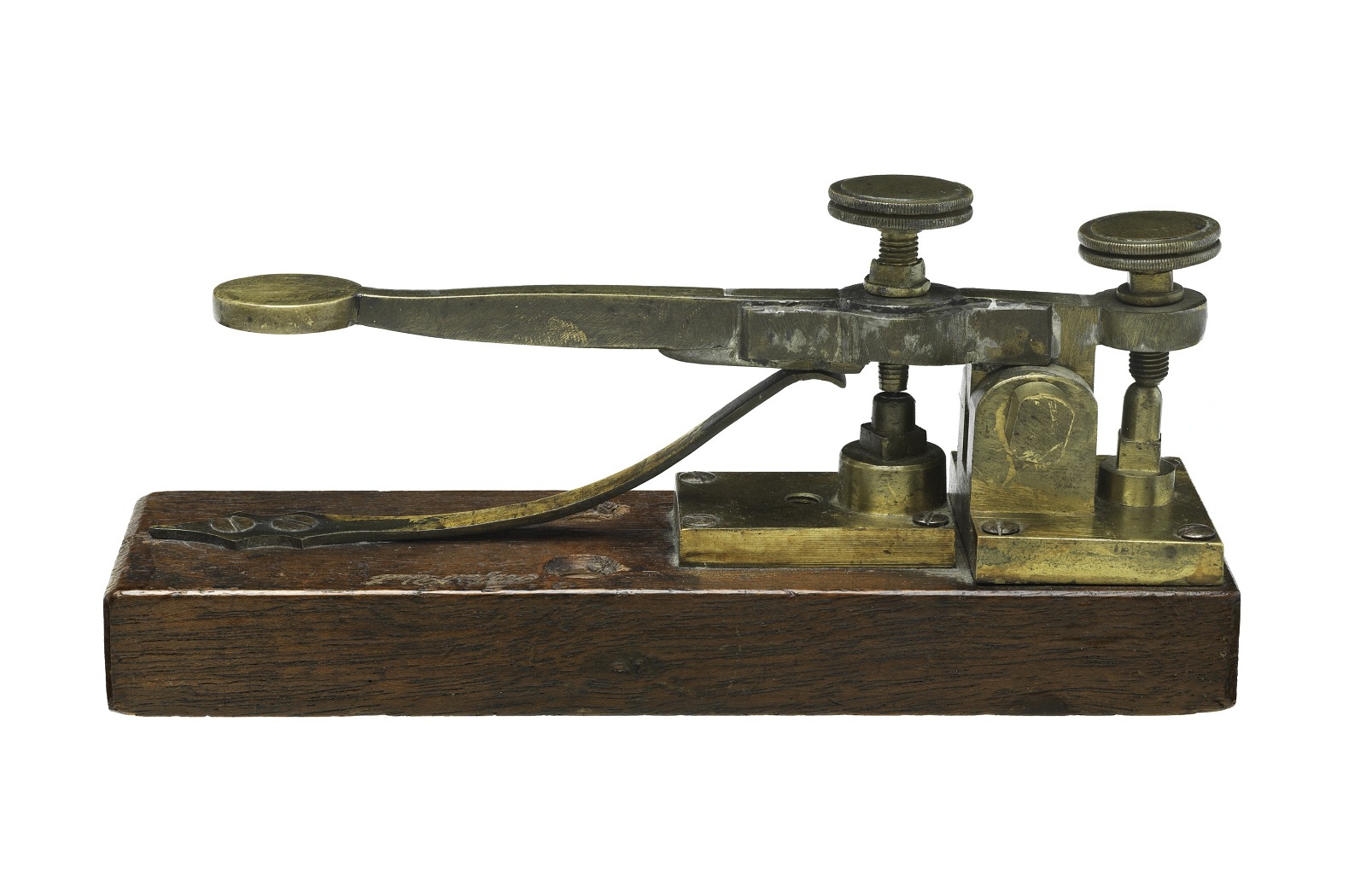

For example, Morse’s telegraph used a pencil to mark paper, while Vail used a steel-pointed pen. The sending key was also Vail’s work, along with other improvements to the receiving apparatus (we’ve seen some nice replicas of this key).

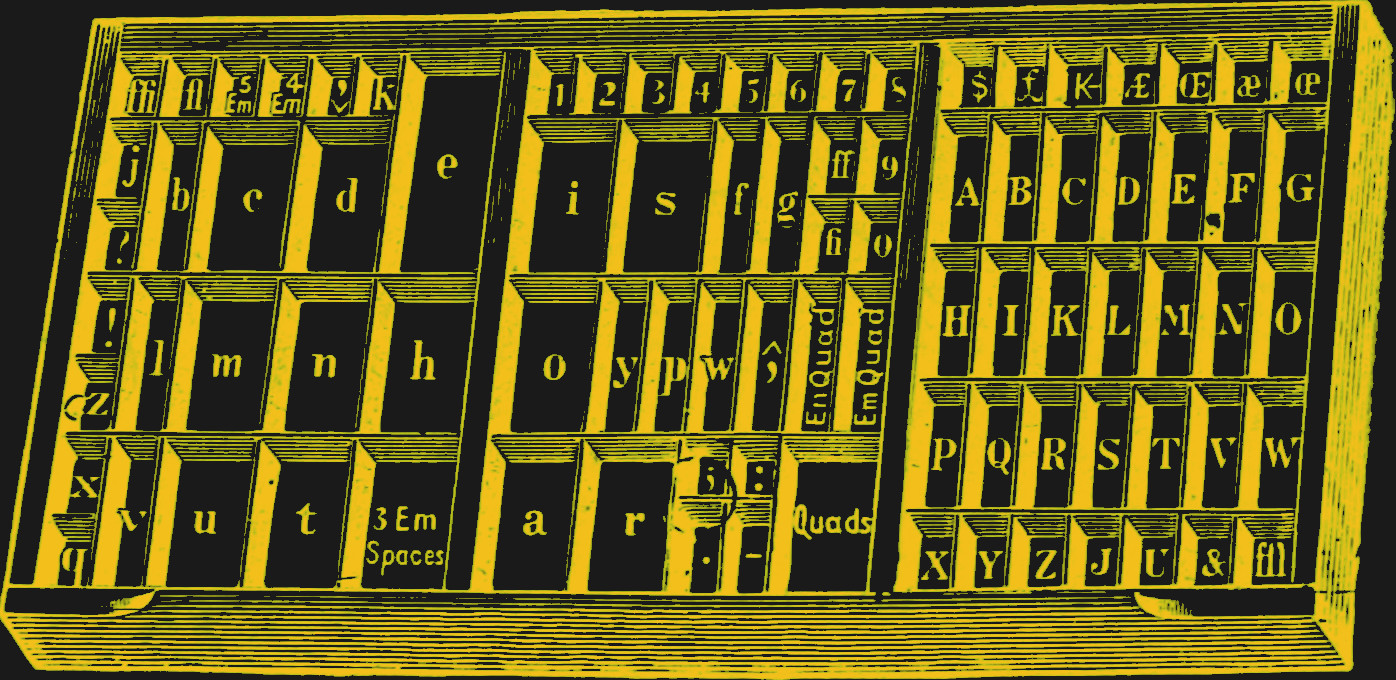

As you may have noticed, the length of Morse code characters is inversely proportional to their frequency in English. That is, “E,” a common letter, is much shorter than a “Z,” which is far less common. Supposedly, Vail went to a local newspaper and used the type cases as a guide for letter frequencies.

Two Types of Code

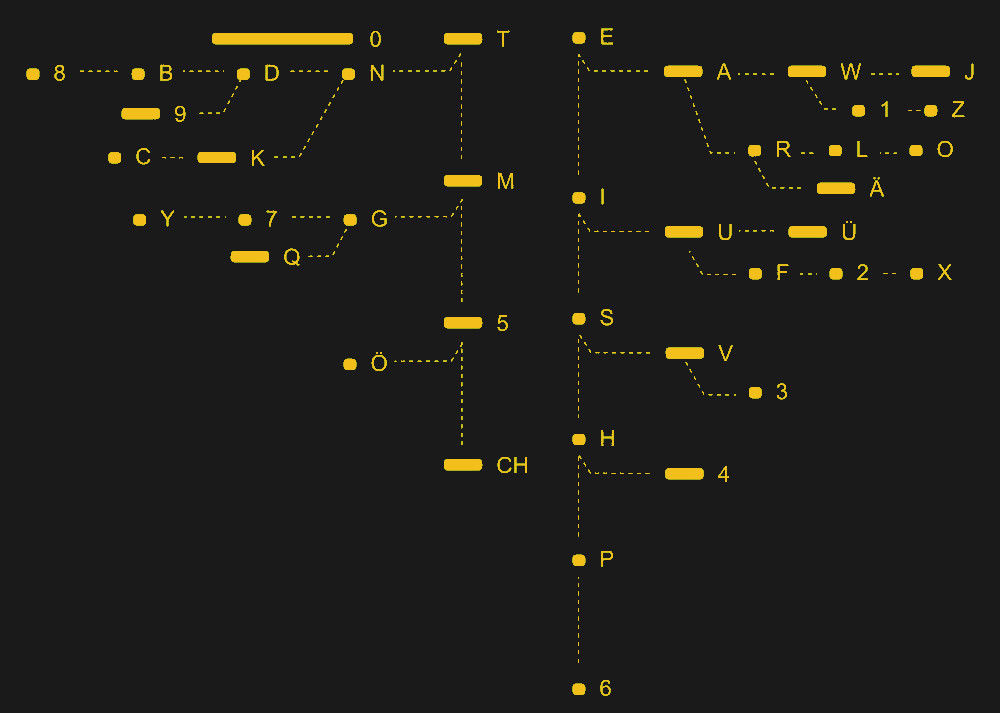

It is worth noting that the code in question isn’t the one we use today. It was “American Morse Code” which was used most often by railroads. The modern International Morse Code is somewhat similar, but several differences exist. The most notable is that dashes are not always the same length. An L is a “long dash,” and a zero is an even longer dash (you occasionally hear this as shorthand on the ham bands if the sender uses a straight key).

In addition, some letters use longer than normal spaces. For example, the letters “A” and “B” are exactly like modern code, but the letter “C” is two dots, a double space, and another dot. An “O” is a dot, a double space, and another dot.

The gaps and different lengths caused problems with long cables, which led to Friedrich Gerke developing a derivative code in 1848. His code is essentially what we use today and uses a fixed length for dots, dashes, and spaces. There is one exception. The original Gerke code used the long-dash zero. Most of the letters in the International code are the same as the ones in the Gerke code, although when International Morse was codified in 1865, there were a few changes to some letters and numbers.

The telegraph was a huge success. By 1854, around 23,000 miles of lines were in operation. Western Union formed in 1851, and by 1866, there was a trans-Atlantic cable.

Will Success Spoil Alfred Vail?

Vail, however, was not a huge success. Morse took on an influential congressman as a partner and cut Vail’s shares in half. That left the Vail brothers with 12.5% of the profits. In 1848, Vail was disillusioned with his $ 900-a-year salary for running the Washington and New Orleans Telegraph Company. He wrote to Morse:

“I have made up my mind to leave the Telegraph to take care of itself, since it cannot take care of me. I shall, in a few months, leave Washington for New Jersey, … and bid adieu to the subject of the Telegraph for some more profitable business.”

He died less than 11 years later, in 1859. Other than researching genealogy, we didn’t find much about what he did in those years.

The Lone Inventor Fiction

Like most inventions, you can’t just point to one person who made the leap alone. In addition to Vail and his assistant William Baxter, Joseph Henry (the inductor guy) created practical electromagnets that were essential to the operation of the telegraph. In fact, he demonstrated how an electromagnet could ring a bell at a distance, which is really all you need for a telegraph, so he has some claim, too.

Part of the Speedwell Ironworks is now a historic site you can visit. It might not be a coincidence that the U.S. Army Signal Corps school was located in New Jersey at Camp Alfred Vail in 1919. Camp Alfred Vail would later become Fort Monmouth and was the home to the Signal Corps until the 1970s.

These old wired telegraphs made a clicking noise instead of a beep. Of course, wired telegraphs would give way to radio, and telegraphy of all kinds would mostly succumb to digital modes. However, you can still find the occasional Morse station.

I think the effort to “retire” Morse code was in fact a genius publicity move to get tons of new people to learn it.

I agree. I’m a no-code Extra and not being forced to learn cw made it an absolute pleasure to learn.

As Mrs. Landingham, rest her soul, might have said “Jed, if you don’t know etaoinshrdlu I don’t wanna know you.”

Interestingly, the ‘l’ slot in the typecase illustration is not as big as the rest of etaoin shrdlu.

Legend says that the “HI” (laughing) was an “HO” originally, exactly because of this detail.

So the original greating in CW was meant to be “HO! HO!”, like Santa’s laughing.

Frankly I think leaving in a snit and then doing nothing for 11 years puts paid to claims of Vail being the mastermind. Start a new company with all the improvements you’ve thought of over the years, work on some weird whackadoodle theory like transmutation of gold, whatever, that’s what the “unsung genius” typically does. Compile ancestry.com charts? Meh.

Tough talk.

Btw, I do remember a child friendly version of history of telegraphy from a educational show named “Discoveries Unlimited”. It’s episode 3.

It’s of course not perfectly faithful, but visual explanation is fine.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discoveries_Unlimited

Englisch intro: https://tinyurl.com/9edxc8wv

Japanese: https://tinyurl.com/2t8rxf7y

German (p1): https://tinyurl.com/4j6axyb5

German (p2): https://tinyurl.com/2u452msn

vy73s, Joshua

Interesting read. I used to enjoy Morse via CW on amateur radio until I got married in 1984 and moved out of my parents’ house and into an apartment with my new wife where antennas were not allowed. I got to where I could take it at about 30wpm without writing it down. The world record is between two and three times that fast; but by that time it almost sounds like one of the early modems. CW is extremely efficient, and on just two watts, I was regularly talking to people thousands of miles away, and my farthest was when I was in Hawaii and contacted someone in the middle east, almost the opposite side of the earth. This was also with a random-length wire antenna supported between the house and a tree. I enjoyed the fact that on CW, the people I’d talk with were more interested in talking technical, rather than cussing about their wife’s shoe collection or some such thing. Morse is not as sterile as many think, either. Especially for operators using a straight key rather than some sort of keyer, I could tune across a band and say, “Ah, there’s ol’ Harry down in New Zealand…and there’s Bob up in Santa Maria…and there’s ,” all from recognizing their “voice,” without waiting for them to identify themselves. You can also tell when they’re laughing, being sarcastic, etc..

The world record for receiving Morse Code is in the vicinity of 250 wpm held by a young Romanian ham. He doesn’t send very fast, though.

The actual world record is FPGA implementation crunching out 1.3 Gwps. Doing morse by hand is nothing but a sado-masochism. You could also bit-bang serial with microswitches, but what’s the point?

Let’s don’t forget about elbugs, though.

Such classics as the ETM-3 or Heathkit HD-1412 with built-in keyer.

The squeeze (iambic) capable models allow very quick operating.

High speed Morse Code is simply a challenge, at least for some folks, and as a result it’s also sometimes a competition. It doesn’t need to have a point beyond that. If you can’t come up with a hundred or more other “pointless” challenges that capture some peoples’ imagination you aren’t thinking very hard.

For ‘voice’ read ‘fist’.

Same thing happened when I used ICQ where u could see each keystroke live. After some time u could read all emotions only by looking at how they pressed the keys and error rates. That’s when I realized I had to cut down the time I spent, plus one of the girls become my gf in real live after one year without any picture, I was lucky.. This was 94-96. Image what each phone can decode when u write now, by using AI. Add the motion sensor on top of that. We are open Books

Alfred Vail was 1st cousin to Theodore Newton Vail, who was instrumental to the development of AT&T.

Samuel Morse and Joseph Henry corresponded with each other following Morse attending a lecture on electromagnetism.

It is interesting the way tech rolled out. Looking back at the pieces they had available back in those days it would have been possible to make a non code based transmitting typewriter with a lot of resistors on the sending end and a meter like thing to index a solenoid over the correct letter on a typewriter like thing on the receiving end. Would have been harder to get right over long spans though, and it would not have worked at all over radio. Still it is interesting how things unfolded when they could have unfolded in very different ways.

Hi, Hellschreiber was technically possible hundreds of years ago with the simple technology of the time.

All it needed was the skill set of a clock maker/typewriter maker.

The cool thing in comparison to fax was that it worked without a photo sensitive part.

It also was compatible with on/off keying and voice modulation (AM, SSB etc).

So morse telegraphy wasn’t “needed” in human history, strictly speaking.

It’s still a nice bonus that it had been invented though.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellschreiber

“… it would have been possible to make a non code based transmitting typewriter …”

Except that the practical typewriter came after Morse code!

My Dad was in the British army ‘Y’ service during WW2, and after VE Day was retrained in Japanese Morse, but VJ Day meant that he was not needed after all. The training did not include Japanese characters; instead they used modified Roman letters with diacritics to transliterate the text. The longest single symbol was known as ‘bosh zed hanigori’ which seemed to go on forever. It was written (iirc) as a Z with an accent above and below. I have just found a reference to hanigori as ‘–..-..–.’ but ‘bosh’ is still a puzzle to me.

Very little is recorded about this phase of the war.

The Morse symbol given above for ‘Hanigori’ might be more clear with embedded spaces in order to separate the dashes, thus:

‘- – . . – . . – – .’

But another source says it is just the final five symbols thus:

‘. . – – .’

There also seems to be some confusion between ‘Ha’, ‘Nigori’ and ‘Hanigori’ (several spellings), which I have been unable to resolve.

I received my tech license when mirse was required which back then was called a tech plus license. Although no code is required any longer, there wouldn’t be near as many in the hobby if ir were.

Morse presented his invention for the first time in 1837. From 1833 to 1845 C. F. Gauß and W. E. Weber had a 1.1 km single wire telegraphy line inside Göttingen. Initially they used a 5 bit binary code for each character, with the polarity of the impulses deciding the bit value. They later switched to a shorter, variable length code with a pause after each character.

(unfortunately both sources in German)

https://www.forum-wissen.de/blog/das-gausssche-telegraphenalphabet/

https://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/document/download/0188fd8f56a96739a307f28545ed41d2.pdf/Gauss_Weber_Telegraf_Magdalena%20Kersting.pdf

two wires, not single wire

For a high-impedance circuit, a single wire would have been sufficient.

The ground connection could then have served as the second wire.