Few anime fans probably know about the name Shigeyuki Hayashi. But under his pen name Rintarô, he belongs to the hall of fame of the most important and influential directors in anime history. He left a considerable legacy in anime history, be it for his huge blockbuster movies such as Galaxy Express 999, Harmagedon: Genma Wars, and Metropolis, which shook the anime landscape forever, or his more experimental works like Download or Take the X Train.

In October, Rintarô was invited to the International Science-Fiction Festival Les Utopiales in Nantes, France. An incredible opportunity to meet this legend who has been involved in anime since its very beginnings, as his first work was as a colorist on The Tale of the White Serpent at Toei Dôga.

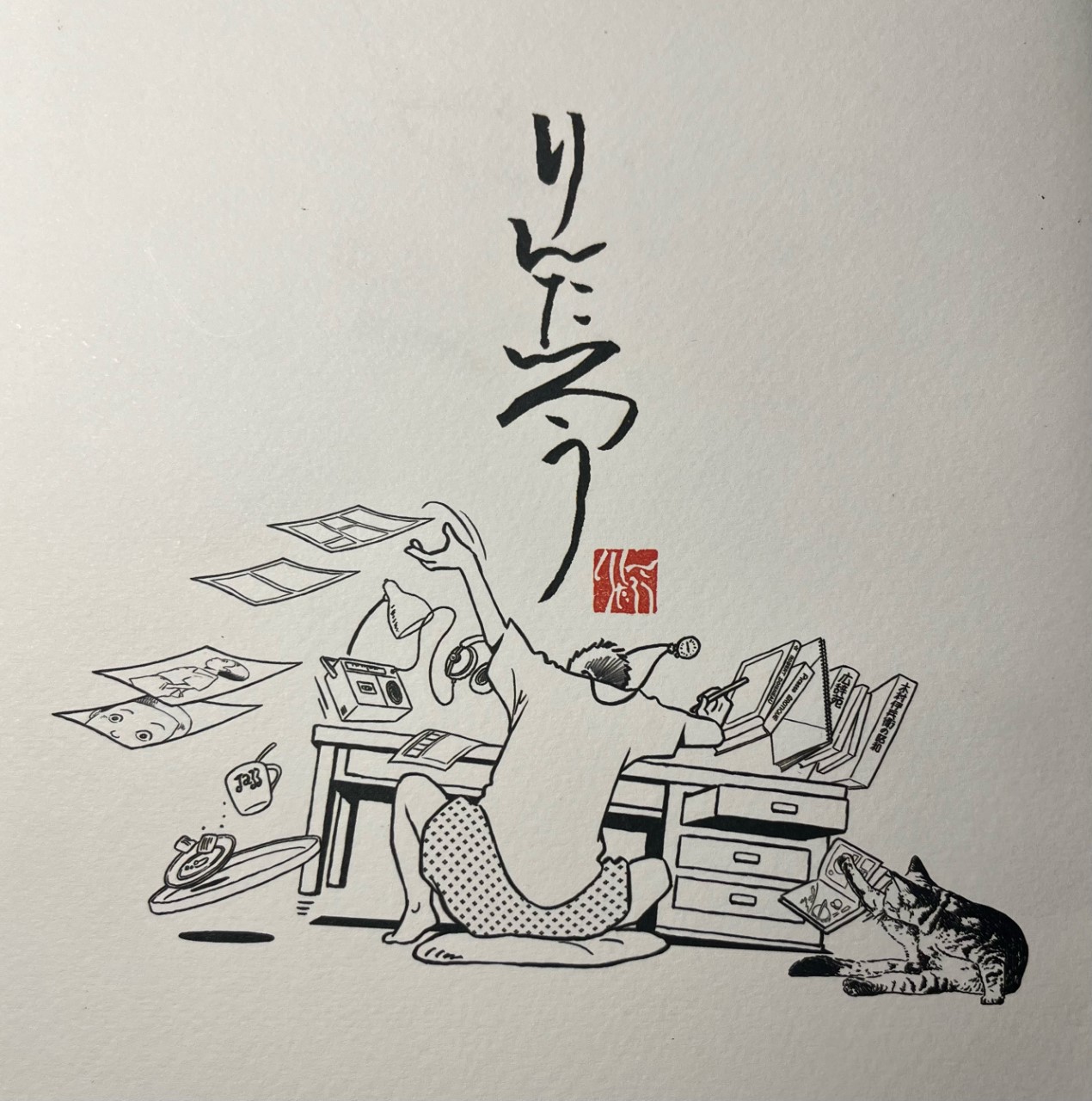

Rintarô also took this opportunity to present the autobiographical Bande Dessinée he is working on. He was very specific about it not being a manga, but Bande Dessinée, a European-style comic proper to France and Belgium – Think Tintin, Asterix, or Largo Winch. The reasons behind it are that this work is done by Rintarô for the enjoyment of his French friends and is, for now, meant to be published only in France. Also, Bande Dessinée does have a more prestigious and artistic connotation in Japan than manga.

Although we did not have the opportunity to meet with director Rintarô or Mr. Masao Maruyama, the founder of animation studios Madhouse and MAPPA, who accompanied him, one on one, we were invited to take part in a press conference where we were able to ask him some of our questions.

We have also recorded every one of his public appearances during the Festival and compiled it in this article. You will be able to read the panel he held and the introduction of each of his movies shown during the event. Every one of them is an insightful moment of anime history and filmmaking.

We hope that our coverage is able to accurately transcribe how fun and insightful these four days with one of anime’s greatest directors were.

Our content is only possible through your help! Support us on Ko-Fi!

Can you tell us about your path to becoming a director and the different roles you occupied before getting there? Have you always aimed to become a director?

Rintarô: My original goal was always to be a director. If I worked in different roles, such as storyboarding or writing scenarios, it was always to become a director. For me, the director is the synthesis of all the jobs in animation. It’s the same for a live-action movie; cinema is, first of all, a collective work, and you have to understand each part of the work in animation, so my early experiences as an animator were always very useful for my career as a director. Even though you don’t write the scenario of a movie as a director, understanding the scenario itself with scenario writing experience is very useful. A director must understand the entirety of animation jobs.

My career as an animator was always very useful in giving good indications to animators. In my mind, animators are the real stars of the animation medium. They’re a lot like actors in live-action cinema, where the director directs the acting. I direct them just like I would direct actors; even though they don’t play the roles, they draw them, so in a way, they are interpreting the roles. Therefore, there must be good communication between the director and his stars, the animators. It’s a very particular work, but for me, it’s the same between animation and live-action. I talk about it like it’s a very serious thing, but we’re having a lot of fun.

Speaking about animators, you often worked with legendary animator Yoshinori Kanada, who left us a few years ago. He had a unique style, and I would like to know how it was to work alongside him and what interested you so much in his style at the time?

Rintarô: I was not expecting to hear the name of Kanada here in Nantes! In the Japanese animation field, there are a lot of extremely talented animators, even more than in the United States at Disney. Still, even among them, Kanada’s talent was just something else. The first time I worked with him was on Galaxy Express 999, and I was really impressed by his talent and sensibility.

In classic animation, like Disney, you animate at 24 frames per second. In Japan, we started with TV series with a very limited budget where we were forced to make very economical choices, and that’s how we came out with a “limited aesthetic.” It all started with the TV adaptation of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, so we were used to animating in less than 24 frames per second. Of course, the mainstream audience doesn’t see the in-between frames in animation because it’s too fast. But to us as professionals, we can always see when something is wrong or different, and we can express ourselves with that small difference. Kanada was particularly good at controlling the number of images and expressing himself artistically by having good control over the number of frames per second.

[Rintarô explains Kanada’s style with a movement of his hand, taking it as an animation example]

Imagine an animation of my hand twisting. It goes from here [at the bottom of his head] to there [to the top of his head]. The director asks the animator to make this move. The hand goes from here to there. The director also gives the duration of that motion. “I want the hand to go from here to there in this amount of seconds.” If we want a fast movement, we make 12 images, so 0.5 seconds. Normal animators are always searching for a movement that’s as smooth as possible. That’s what Disney does perfectly. And what was really impressive about Yoshinori Kanada was that there was a frame in the animation that didn’t match the motion at all. Like in the example I am giving, he would add a closed fist for no reason. He was mixing drawings that weren’t supposed to be there with the motion. But when you look at his finished animation, it’s always extremely beautiful to look at. That’s because, with just the addition of that one special frame, Kanada could show the character’s personality and originality. That process is unique to animation. Kanada and I always worked together to find particular and special movements, and that’s how we created those extraordinary scenes. Those special images I’m talking about aren’t normally seen when watching the finished work, but you can easily find the specific image when you slow it down. Kanada was extremely proud of it and was aware of the consequences of that addition to the overall quality of the animation.

We used that technique to create beautiful animation; however, some other people used that same technique for other goals. In the USA, they used it for advertisement. In a movie, they would put subliminal images of Coca-Cola. It became really controversial, and they can’t do that anymore. This added subliminal image isn’t something you see clearly, but it speaks to your mind. Adolf Hitler used that process for his political propaganda and brainwashing. In the USA, they stopped doing this because it was very controversial. But in Japan, it always was a real way to express ourselves artistically, and Kanada was very aware of the artistic potential of that method.

You worked with Osamu Tezuka at Mushi Production on Astro Boy, and years after, you directed the masterpiece Metropolis, which is an adaptation of his second manga. The animation is completely different from the Astro Boy anime. Were this adaptation and that manner of animating Tezuka’s manga on your mind for a long time before making Metropolis?

Rintarô: The first time I directed anime was on Astro Boy episodes, and I’m still thankful to Osamu Tezuka, who requested me to do that. Then I also directed episodes of Kimba the White Lion, but I never thought to direct an adaptation of Metropolis at the time. Then I left Mushi Productions, and I worked on many other anime that had nothing to do with Osamu Tezuka, but I always had in mind that my starting point was Osamu Tezuka. I felt like I had to do something of high quality with his work because I’d always regretted not reaching its absolute potential. I was only 22 years old at the time, and in retrospect, I think I wasn’t good enough. Tezuka was also young, in his thirties, but in any case, I’d always had that frustration of not having the skills yet to direct an Osamu Tezuka adaptation. Thirty years later, I started to think about it seriously, and I felt like I had to do something about it. That’s how I came up with the idea to adapt Metropolis that Tezuka created when he was only 21 years old and studying to be a doctor. The Metropolis manga is part of a trilogy alongside Lost World and Next World. That was Tezuka’s starting point. I liked the urban atmosphere of it. Also, at the time, I think he was really influenced by Disney a lot. Just look at his paneling or the arms of his characters, which are very thick. They look like Disney’s characters at the time! Personally, I think that even at the time, his level was already superior to Disney’s. Personally, I think that Tezuka had always wanted it to be adapted for the big screen, just like Disney movies, so it motivated me to adapt it as a movie. I talked about it with Katsuhiro Otomo, with whom I had already worked, and that’s how we started to make this movie together.

You’re currently writing and drawing an autobiographical Bande Dessinée. What is the ambition behind it, and what specific period of your life do you want to describe in it?

Rintarô: I have a lot of friends in Paris, including Shoko, that is currently translating for me, and those friends of mine have always told me that they were interested in the history of Japanese animation. They wanted to understand the historical contexts behind it. They made me realize that I really lived the history of Japanese animation, I’ve followed its entire evolution, so my life is, in a way, representative of Japanese animation’s history. Therefore my friends told me I had to tell that in a Bande Dessinée.

I had never intended to make manga in Japan, but listening to my friends, I thought, why not, and I took my decision without much hesitation. That’s how I started to draw this story, first on the human level but also how it all started, what people were eating at the time, and many different things. But after accepting it, I regretted it a bit because I didn’t realize how difficult this work would be. I started to regret it. [laughs] Right now, I’m 81 years old so telling what happened during such a long period is not easy. Also, I’ve always wondered if I would die before I finished it. I’ll tell you a bit about what I prepared. The Metropolis movie is very special and important to me, so I decided that my Bande Dessinée starts with Metropolis, as a kid when I read Tezuka’s manga, and ends with Metropolis when I made the movie so that it represents the synthesis of my whole life.

Is cycling still an important part of your life?

Do you know Bernard Hinault? Since he became a French cycling champion, I’ve always followed him on TV as well as others, such as Laurent Jalabert. When I was a kid, no bike was specially made for children. All bikes were for adults. Also, unlike in France or Belgium, in Japan, there were no sports bikes. There were only bikes for daily usage. And since there were only bikes for adults, children like me had to climb on those bikes that were way too big for them. Do you know how we climbed those things? Let’s imagine I’m still a child…

[Rintarô starts posing and climbing on the table and explains how he was biking then.]

At the time, bikes were mostly used by delivery men. Normal people didn’t own them. This way of biking I showed you was called the triangle, and that was how those delivery men were mostly using it, so when I saw Bernard Hinault on TV, I thought, “Hey! I don’t know that bike and the way he’s using it!” So I really wanted to own the same bike as Bernard Hinault, and I was impressed by the huge price of those bikes. Obviously, the same model was too expensive, but in Japan, we could find reproductions of some models used by European cyclists. But even that was super expensive; it was around 700.000 yen. To be able to buy it, I made some storyboards I didn’t really want to make. Nowadays, I ride my bike less because it’s not very easy at my age, and when I get passed by young girls faster than me, it pisses me off! [laughs]

People often ask me: if you could start your life over, would you still be making anime? And I always answer: “No, I wouldn’t make anime. I’d be a cyclist, and I’d participate in well-known bicycle races such as the Tour de France.”

How did you hear of this French Science Fiction Convention, “Les Utopiales,” and what do you think of it?

Rintarô: I didn’t know about “Les Utopiales” at all at first. My friend Shoko told me about it, saying they were interested in inviting me.

One day, I received a letter from Frédéric Temps, responsible for the convention’s cinema section, saying they wanted to invite me to the next edition. I found it interesting because I was mostly invited to anime conventions in my life, and that was the first time I was invited to a convention specialized in Science Fiction. I’m truly honored to be invited to “Les Utopiales” and to be here with you today in Nantes. It is a town that has always interested me because it’s the city of Jules Verne, whom I’ve always loved since my childhood. Also, when I was looking at the Tour de France, I saw the pedestrians on a bridge in Nantes, and I saw the Loire river, and I said to myself that I wanted to be there. Now my dream has come true!

What do you think about the first Harlock TV series’ huge success in France, which was released here under the name Albator? Why do you think it was so successful here?

Rintarô: Many people have already told me that Albator was a huge success in France, but personally, I never understood why this series had encountered such a success here. At the time, I heard that it wasn’t just a success with anime fans, but the mainstream public also really liked the series. That made me very curious. One day someone brought me a french VHS tape of the series, and I was extremely baffled by this French version of Harlock. The whole soundtrack and tons of other stuff were changed. Even now, I ask myself why people liked this series. I think it’s mostly Harlock’s character that people liked. He is an anti-authority type of character, a hero always fighting against any form of power and control, the total opposite of a conformist person. I worked hard to show this side of the character in the series. His lonely attitude, striking character design with his hidden eye, and his way of wearing his coat. Even his motions were all made to show his anti-authority aspect. That surely is what was acclaimed in France, just like in Japan. But to me, cinema isn’t just images and narration. There is also a very important element which is the soundtrack. At the time, I worked hard with the composer Seiji Yokoyama to show Harlock’s character in the best way possible. Therefore, after all that work we put into the soundtrack, I was baffled when I saw the French version without the music we purposefully made.

Since middle school, I have been a cinema lover, I watched a lot of French and Italian movies, and I was particularly into French Noir cinema, in which there was modern jazz music I loved. That’s why each time I made a series or movie, I always worked a lot on the soundtrack. When I learned that France, a country whose history is filled with cinema, dared to disrespect the soundtrack of a work of art, it shocked me. I was very moved when I learned that “Les Utopiales” chose to show the original version of Harlock for its screenings because they’re a team that respects artists. I’m really happy about that.

On the second day of the event, Rintarô held a one-and-a-half-hour panel hosted by Hervé De la Haye.

Hervé De la Haye is an independent researcher on the topic of animation who is responsible for finding some lost media, such as the French pilot episode of Ulysse 31, as well as the never broadcast English version of Ulysse 31.

The panel covered the most important parts of Rintarô’s career, from his beginnings at Toei Dôga, his directorial debut at Mushi Production, his return to Toei, and his ventures with Studio Madhouse.

Hervé De la Haye: You were born in 1941, and you are one of the pioneers of Japanese animation. What are your oldest memories about your career in animation?

Rintarô: First, I would say I congratulate myself for having lived for 81 years [laughs]. I discovered cinema when I was eight years old, in 1948, which was a very strange experience for me at the time. It was a huge surprise. It was a soviet movie called The Stone Flower. This movie was subtitled in Japanese, but for an eight-year-old kid, it was very difficult to understand. What was the most striking to me was not really what was happening on screen but what was going on behind me with the movie projector; it felt like a magical world. Obviously, everyone was watching the screen, but I was so interested in the projector that I stood next to the projectionist. I think that it was at that moment that I became possessed by the magic of cinema.

Hervé De la Haye: In 1958, you worked as a colorist on the movie The Tale of the White Serpent, which was the first Japanese animated feature film in color, produced by Toei Douga. Could you tell us some memories of that time and how you got into the graphic arts industry to become a colorist on that movie?

Rintarô: Before working at Toei, I worked in a small advertising company specializing in animation, where I learned the basics of animation. But after I finished my training there, the company went bankrupt. One day, while I was eating my lunch at a restaurant, my neighbor was reading the newspaper, and I took it from him because I found an article that got my attention. It was an article talking about Toei Douga, that was currently producing the first colored animated feature film, The Tale of the White Snake. I rushed home to write a letter to Toei telling them I absolutely wanted to work on that project and that I was born for it. I wrote a bunch of lies in that letter because I really wanted to work on that film [laughs]. I was good at making up nonsense. Three months later, I received a postcard from Toei. It was written: “We read your letter and we saw that you were very enthusiastic. We’re going to organize an entrance exam and if you want, you could try to take it.”. I could no longer turn back, and that’s how I ended up trapped at Toei.

Hervé De la Haye: In 1961, you started working at Mushi Productions. How did you start working there?

Rintarô: The story is very simple. I started working at Toei but working there was boring. Their productions weren’t interesting to me, so I was not working well. I was always skipping work. I was getting paid not to work [laughs]. I was considered a really bad employee. I understood that I didn’t have a future in that studio and felt I was about to be fired. At the time, Osamu Tezuka created his own animation studio, and one of my former co-workers who was already working there suggested I join him. That’s how I arrived at Mushi Productions.

Hervé De la Haye: There, you worked on Astro Boy, the first TV anime series. Could you tell us about your experience and what it was like to work at Mushi Productions in its beginnings?

Rintarô: Osamu Tezuka as a mangaka was already popular, but he was dreaming of making animation, so he decided to create his own studio. He hired about 30 people, most of them older than me. That’s how the first team was made. At first, we made rather experimental movies, very personal films by Osamu Tezuka. I worked as an animator on those projects. At that time, the first difficulties started to appear. The salary of those 30 people was given thanks to the money Osamu Tezuka earned as a mangaka, and those experimental movies weren’t commercial at all. You can understand how much money Tezuka could earn as a mangaka as a man being able to give a salary to 30 persons. So we, 30 young people, were wondering if we could continue depending on a mangaka’s salary. We thought about projects that could make the studio profitable as a company, financially speaking. We thought about making an animated feature film, but that was too complicated as we were only 30, there was not enough budget, and we didn’t have any movie theater network since we weren’t distributors. At that time, televisions were just starting to enter people’s homes.

Originally people’s greatest entertainment was cinema, but it was a moment of transition where TV was getting increasingly popular and was starting to surpass cinema as people’s greatest form of entertainment. Knowing that context, we decided to get into TV series production. We discussed this with Tezuka and decided to adapt his manga Astro Boy. After this decision, things started to get a lot more complicated because we only had experience with animated feature films, and normally, creating a film takes one or two years. In a TV series, we must produce one episode per week. It was unthinkable at the time because of how long a movie production could last; it could even take three years. One episode per week felt like an insurmountable challenge. We thought we couldn’t do it, but Tezuka told us it was possible. At the time, Tezuka was watching a lot of American TV animation, and he told us about the limited animation of those series. Limited animation means that only the most important key images are part of the animation, so there are fewer in-between frames. To simply explain limited animation, imagine I am Astro Boy. If he speaks, instead of doing the drawings of every image, his face is a still image, and you only have to animate his mouth.

Hervé De la Haye: In France, people often say that Tezuka is the Japanese Hergé or that he is comparable to Disney. I think those comparisons are not very accurate. Could you tell us what is, for you, the importance of Tezuka in the cultural history of Japan?

Rintarô: Tezuka wasn’t world-famous at the time, but he was already extremely famous in Japan. He had liked drawing manga since childhood, but he also aimed to become a doctor. I don’t know what degree he got exactly, but he got a medical degree. His parents dreamt that their son would become a doctor, but since he loved manga, he was always drawing, even secretly, during the war. He published a very important manga trilogy when he was only 21. The first work in it is Lost World, the second is Metropolis, and the third is Next World. With this trilogy, he completely revolutionized Japanese manga style. His paneling was extremely cinematographic. Manga history in Japan is very long, but it’s really Tezuka that changed modern manga forever, so much so that he was considered the God of Manga.

Hervé De la Haye: You quickly grew in stature at Mushi Productions and became a director on the first Kimba the White Lion TV series. The studio started to have financial difficulties, and you worked with other studios. You started naming yourself Rintarô, a nickname given by your colleagues.

In 1977, Mushi Productions, having gone bankrupt, Tezuka went to Toei to produce his new series, so you went back as well to work as a chief director for Jetter Mars.

In 1978, you directed the first Space Pirate Captain Harlock TV series, which French release is very popular here in France under the name Albator. At the time, we even talked about the “Albator generation.”

However, this version is very different from the original since a different soundtrack of questionable quality replaced Seiji Yokoyama’s music. How did you become aware of that, and what do you think of this transformation? How could Toei have accepted such a thing?

Rintarô: [Rintarô pauses and takes a very serious voice] It might be very long… I have so much resentment; it will be long. [the whole room laughs] Haha, I’m just joking! As I said before, I almost got fired from Toei, so I changed my name and came back under the name of Rintarô. I knew a certain Toei producer very well, and he liked my style a lot. He came to me because he wanted me to direct his new series, which was Captain Harlock. Then I started reading the original Harlock manga. To be honest, the story and the narration didn’t attract me that much, but the character of Harlock with his hidden eye and scars interested me so much that I wanted to create my original view of the character with my style.

Of course, I decided to keep the essence of the original manga and the most important themes, but I absolutely needed to work with the scriptwriter to create a new approach to the character. Music is an extremely important element to me each time I work on a project because it also participates in storytelling. One of the differences with the original manga is a little girl called Mayu, which doesn’t appear in the manga. Leiji Matsumoto often creates young boy characters but not so many young girls. I found that to better show Harlock’s personality, there must be another character very different from him. At the time, people often liked anime with a lot of flashy colors, but I wanted black to be the main color of the series. It was some kind of experimentation for a TV series at the time. It’s not that I particularly like black; it’s just that I found that to show Harlock’s personality better, there had to be a particular color. You can express his personality with just the black color of his coat. So we discussed many things like that with my team to get the final product.

It’s worth noting that the director rarely talked with the soundtrack composer at the time for TV anime series. But because I love modern jazz like Miles Davis’s music, I asked the producer to let me talk directly with the composer Seiji Yokoyama. I told him to make the music feel Harlock’s sadness and melancholy without him saying a word. We feel his sadness through the silence, and that’s what I wanted to transmit with the music. We worked together, him with the music and me with the images, and when I saw the final result, I was extremely satisfied; I was really proud and wanted to show it to everyone. Then a lot later, I learned that in France and Italy, Harlock encountered great success, and while I was coming to Paris, people told me that Albator was highly popular, and I was asking myself why. I had a vague idea; maybe people liked the character of Harlock, who is a lone wolf but has a melancholic side. To better know why Harlock had such success in France, I got a VHS of the French version of Harlock, but when I saw it, I wanted to die.

Hervé De la Haye: I think now is a good time to tell the French public: don’t watch this series in its French version.

Rintarô: Yeah, really, don’t watch it.

But there is something else that shocked me even more. I was so disappointed because when I started to watch a lot of movies when I was a middle schooler, I watched a lot of french movies. I loved the french noir movies, for example, Elevator to the Gallows by Louis Malle. I greatly respected French cinema and France in general, so I asked myself, “Why?! How could France do something so foolish?!” I’m really happy to finally be able to say that. [laughs]

Hervé De la Haye: A bit after that, you direct your first animated feature film Galaxy Express 999. Toei produced that movie after producing a TV series adapted from a Leiji Matsumoto manga.

You didn’t work on the TV series, so when Toei asked you to direct that movie, did they ask you to create a new manga adaptation or an adaptation of the TV series? How much freedom did you have working on that movie?

Rintarô: You’re asking me things that force me to go into detail. I think I might take a very long time once more. First, I would say that at Toei, when a TV series or a movie is produced, the president, the higher-ups, etc., come to see them at the first projection of the finished product. They came to see the first episode of Harlock. So the president at that time, Chiaki Imada, was there and… he cried! Normally the boss of a company doesn’t cry in front of everyone, but he actually cried while watching this first episode. Toei decided to make an animated feature film of Galaxy Express 999, and Chiaki Imada absolutely wanted me to direct that movie because of that. He didn’t remember my name, and because my name “Rintarô” is only written in hiragana, which is very rare in Japan, he said, “This man with this weird writing for his name, I want him to be the director.” I told myself, thankfully, I had this writing for my name because this is what the president remembered.

Later, I learned that at Toei, big projects like feature films were reserved for the elite directors of the studio and that it was not common to call for an external director who isn’t part of the studio for such a project.

Hervé De la Haye: You said that making an animated feature film took 2 to 3 years. But in your filmography, between the spring of 1978 and the summer of 1981 so during three years, you directed the Captain Harlock 42 episodes TV series, the Galaxy Express 999 movie, the 35 episodes TV show Gambare Genki, and finally, the Adieu Galaxy Express 999 movie. How was it possible for you to make two series and two movies in only three years?

Rintarô: You’re right. That’s indeed an impossible feat, so normally I couldn’t have done that. Actually, I was working on several projects at the same time. It’s a bit like the “dissolve” filmmaking technique; the projects overlapped. You’re often busy when you’re a director, but when the artistic team is working, the director can sometimes have some free time. So I used those chunks of free time to work on many things during those three years.

Hervé De la Haye: At the beginning of the eighties, you started working almost exclusively for studio Madhouse, founded by former Mushi Productions members: Masao Maruyama and Osamu Dezaki. It’s quite exceptional because, right now, in this room, Masao Maruyama is here with us. He produced a very high number of great movies, not only Rintarô’s but also other highly important directors. So today, I want to tell Mr. Maruyama: Thank you very much.

Your first feature film at Madhouse was Harmagedon: Genma Wars, released in 1983, which is a movie quite different from your previous ones as it is aimed at an adult audience. At this time, did you feel the need to make something different?

Rintarô: I didn’t intend to specifically make a movie for adults. I didn’t have any target audience in mind, but I wanted to make something that suited my level as a director at the time. Maruyama might be in a better position to talk about this, but I think that Harmagedon: Genma Wars was a real turning point in Japanese animation; it had a big impact on its history. Before, animated feature films were always produced by big production companies that had networks of distribution or movie theaters, such as Toei, Nikkatsu, etc. However, Harmagedon: Genma Wars was funded by a publishing company. One day, the president of the company Kadokawa, Haruki Kadokawa, who was considered the enfant terrible of the publishing world, wrote me some kind of a love letter telling me that he wanted to meet me. I came to see him, and he made me an offer to make something very different from what I had previously done, for example, at Toei.

I was excited to be able to make new things with that project, and I thought I could go to the top of my ambitions regarding creative freedom. I accepted his proposition with great pleasure. Haruki Kadokawa was an extraordinary man, and he told me I had total freedom for this movie and that he would never intervene in the content. He gave me 250 million yen to use freely for that film. It made me want to run away with the money [laughs]. It was just our first meeting, and I was really surprised and lost by such a huge amount of money. At the time, I was independent and didn’t have my own team. I went to Madhouse for advice from Maruyama. I requested Katsuhiro Otomo for the character designs. In Harmagedon: Genma Wars, there is a female character called Luna, and when Otomo drew her, Maruyama thought she wasn’t cute at all. For him, female anime characters should be cute. Otomo replied that he was completely unable to draw cute girls.

Personally, I was very satisfied with Otomo’s drawings. It’s worth noticing that before Genma Wars, anime backgrounds were very often imaginary worlds, so it was stylized, and it allowed us to not be extremely precise or accurate. But for this movie, we wanted to push realism very far. For example, we took real references from the Shinjuku train station for the movie’s train station. For the character designs, we asked ourselves what kind of real clothes the characters would wear, sneakers, leather shoes, branded shoes? We worked on the precision of each accessory. I realized afterward that many movies made after Genma Wars used backgrounds and character designs accurately referencing real places, clothes, and accessories.

Hervé De la Haye: In 2001, your movie Metropolis was a worldwide success. It’s a very ambitious project because you adapt a manga from Tezuka, inspired by the movie by Fritz Lang. Katsuhiro Otomo wrote the script. Don’t you think, as a director, that it is kind of a crazy project to make, after Fritz Lang, a second movie named Metropolis?

Rintarô: It wasn’t a problem for me, but I remember that at the time, with Otomo, we asked ourselves if Tezuka had seen the movie. We don’t know. Maybe he saw it, there are some clues that might say that he saw the movie, but there is no confirmation. The movie by Fritz Lang wasn’t our concern. What was clear to us was that we would make something very different from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

Hervé De la Haye: The script takes a lot of freedom from Tezuka’s manga, but the tone is very different. The manga has a lighter, funnier tone, but the movie is more serious and extremely spectacular. How did that shift in the adaptation appear, and how did you make those choices?

Rintarô: As you say, the manga from Tezuka has a light tone and is funny, but above all, there is kind of a narration issue. It works well when you read the manga, but it doesn’t work at all if you take the same thing as a movie. We decided to keep the essence of the original manga, for example, the Megalopolis background, this image of a transforming girl, and all the most important elements of the original work. We talked with Otomo and decided to focus on the importance of machines because machines were starting to be a huge part of our daily lives. It’s just my personal opinion, but people often say that the year 1941 was the year of the “machine age” in America. It meant machines like planes or electrical household appliances. This is coincidently the year of my birth, and I wanted to insert this “machine age” atmosphere, the feeling of amazement at the view of those machines or the beauty of those machines’ designs. In the original manga, there is a line saying that even if those machines made life easier for us in many ways and gave us greater comfort, they might also make us unhappy and destroy humanity. We wanted to keep that line as a theme for the movie, so inevitably, the movie became quite dark.

Hervé De la Haye: Metropolis successfully uses 2D animation for the characters and backgrounds and 3DCG animation for machines. What kind of challenges have you encountered while combining those different techniques?

Rintarô: At the time, 3DCG animation was already there, like in George Lucas’s movies, even though it wasn’t as developed as it is nowadays. But what was important for me while using both 2D and 3DCG animation was to merge two very different techniques. Metropolis tells the story of a fight between humanity and machines, and I wanted to use 2D to show humanity and 3DCG to show the world of machines. Nowadays, we have many kinds of extraordinary software and applications for 3DCG. However, at the time, even Maya was still in development in the USA, so we had to use tools that were not ready enough. It was extremely difficult to work with 3DCG animation. We did and redid the animation many times; we changed our ideas… I have the image of the Babel Tower in mind when I think about that experience. I think I could never redo such a film, given the hardships we encountered.

Hervé De la Haye: I was told you played the bass clarinet for the Metropolis score. Is that true?

Rintarô: Yes, I did 🙂

Hervé De la Haye: You’re currently working on an autobiographical Bande Dessinée project. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

Rintarô: At 81 years old, I’m a beginner Bande Dessinée author. It will be my first Bande Dessinée and my last one. I have a lot of friends in Paris, for example, my interpreter Shoko, and they love Japanese animation. They told me they wanted to know the historical and social context of the creation of the anime movies and TV series they love. Since I’ve lived the entire history of it, I’m often told I’m an encyclopedia of Japanese animation history and that I had to tell that story as a comic. It’s been three years since I started working on that project.

Hervé De la Haye: Can you show us some drawings of it?

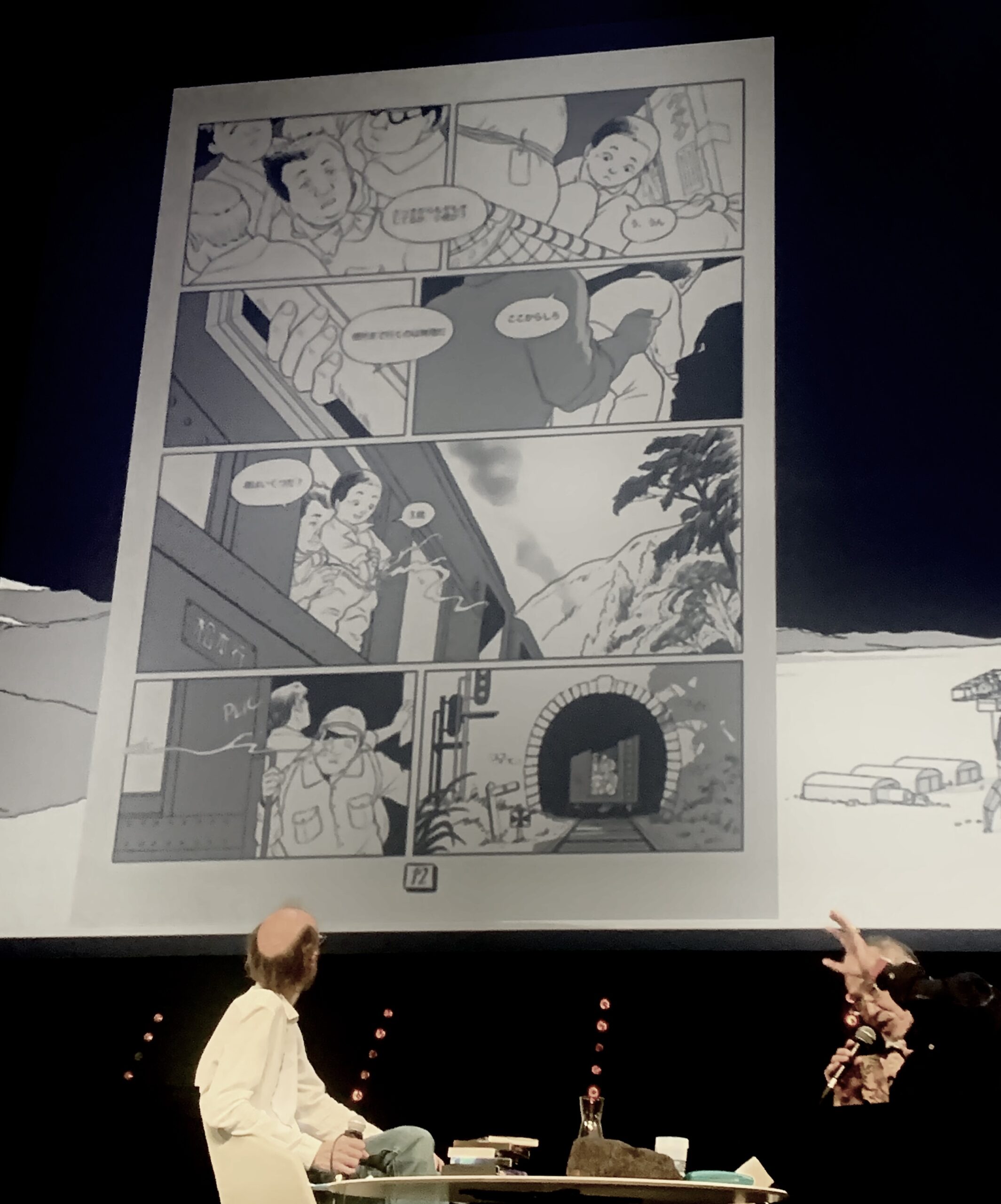

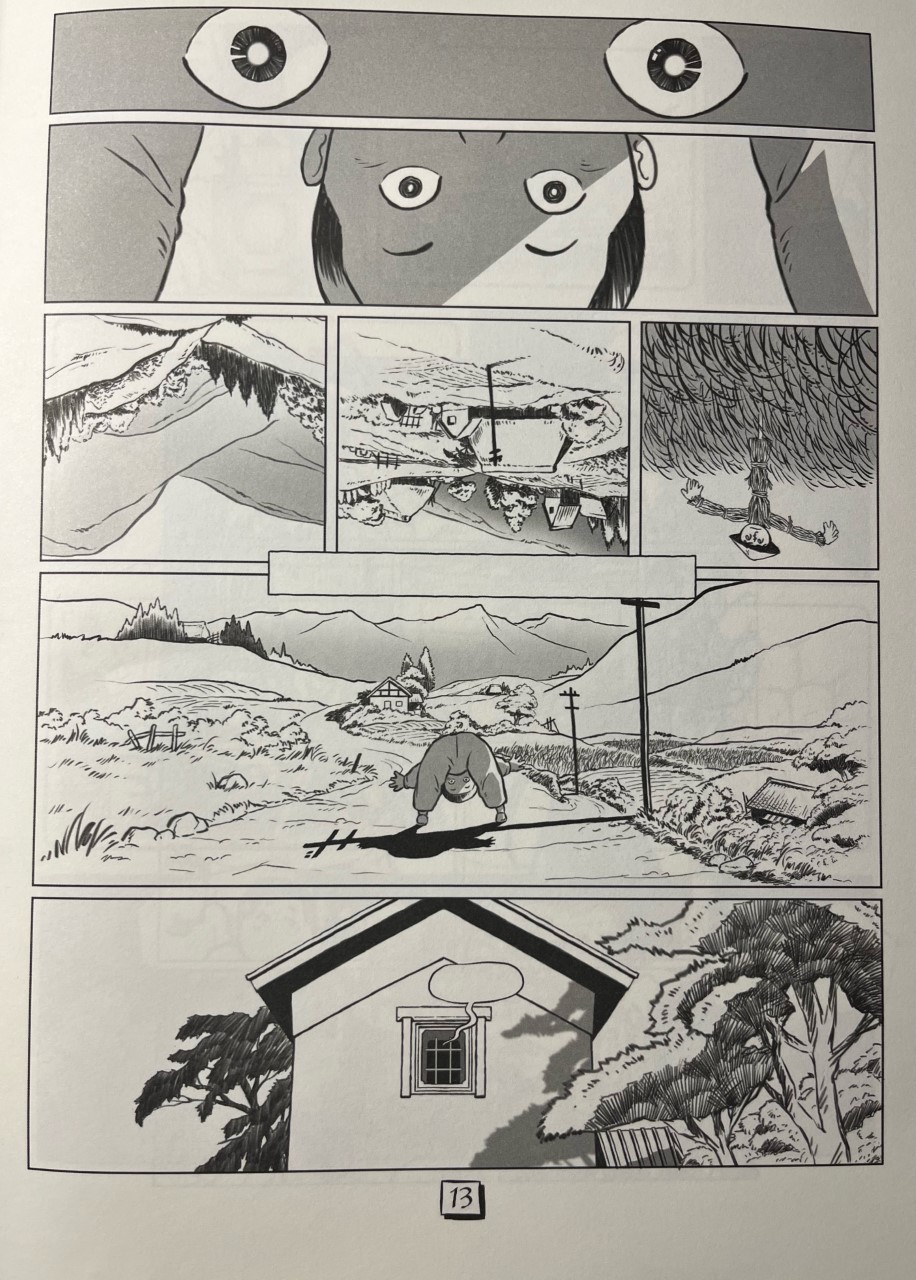

Rintarô: I’ve brought some pages with me. I’ll show you, let me just find them… This page is set in the year 1941; you can see the war’s outbreak on the top right panel. Both Maruyama and I were born in 1941. As the Americans started to bomb Tokyo, citizens were taking refuge in the countryside. Here, I was entering a steam train, which was truly overcrowded. All those people wanted to take refuge, and since children didn’t have any room, adults put me on the net where you normally put the luggage. On the third strip, you see that boy, that’s me!

Actually, I was a lot cuter than this drawing. I was three years old when I took that train, and obviously, I wanted to pee at some point. I held back all this time, but someone noticed I needed to pee. I couldn’t go to the toilet, so I did it through the window, and I still remember how good it felt. [laughs] I still remember that wonderful image of the sun and my pee shining through the sunlight. I had held back for so many hours my bladder was full. You can’t believe the quantity of pee that came out! And I told you this train was overcrowded, right? So a lot of people received my pee in their faces!

This is towards the beginning of my Bande Dessinée. My family moved to the countryside, but the deep kind of countryside.

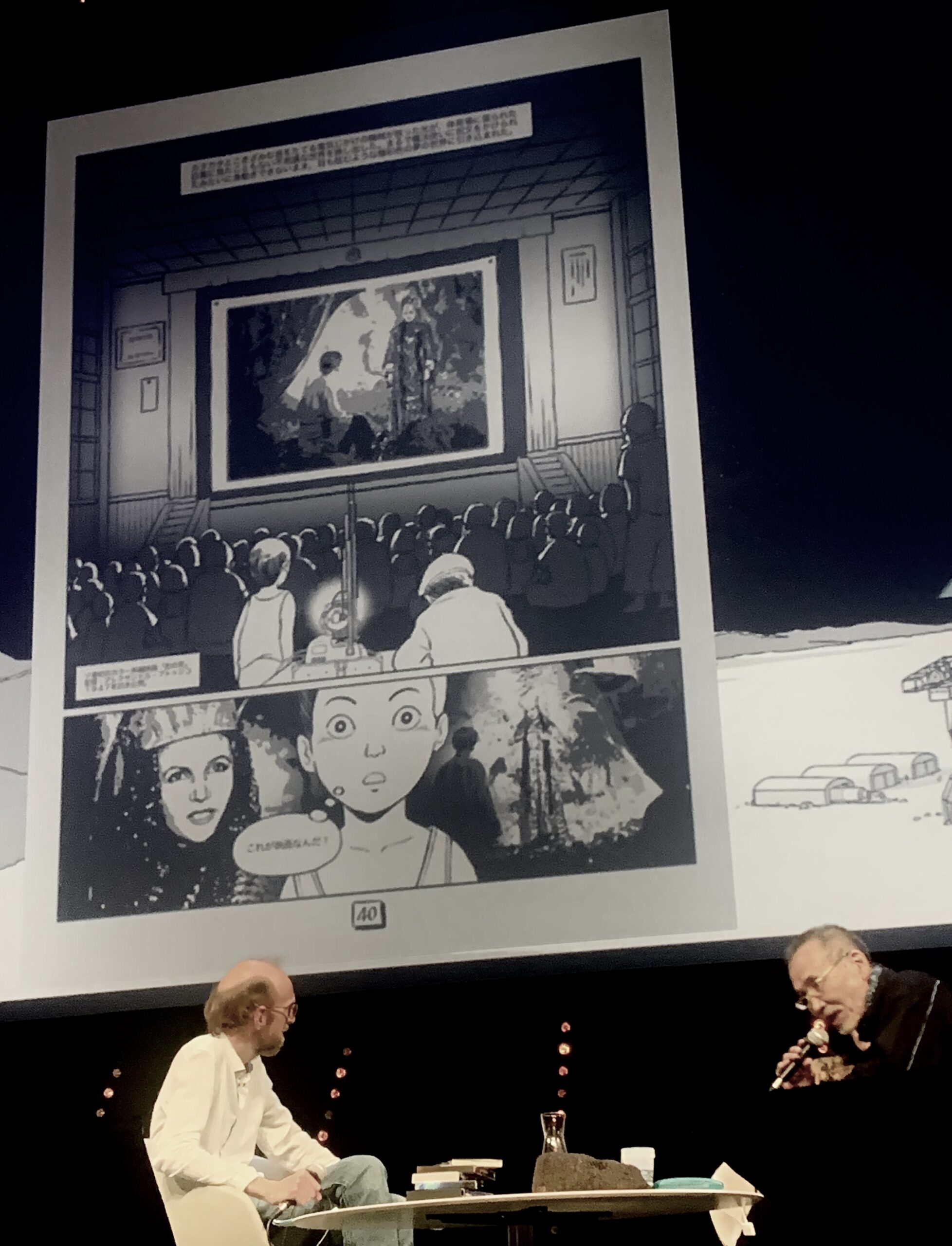

This page shows my discovery of cinema with the film I watched at eight years old I told you about, The Stone Flower. It was a mobile screening, and it was shown at my primary school gymnasium. Of course, I was attracted to the movie, but the projector also appealed to me, and that’s why you can see me near that projector in that panel. At the time, I didn’t even know the word “projector,” so I thought it was a magical box. Truly, I think it’s the day when the magic of cinema started to haunt me.

I’m also talking about my daily life, at school, when I was biking… Life was peaceful there, but at the same time, the atomic bomb struck Hiroshima. But really, my life as a refugee in the countryside was quite peaceful.

At ten years old, my family and I went back to Tokyo. The city had been bombed, but it was rebuilt step by step, and Shinjuku’s scenery changed more and more over time. Adults started to dress in a very modern way, most cars were foreign, and buses started circulating through the city. Here I tell my life as a teenager living in Tokyo and how the atmosphere of the Shinjuku district was. Since the city was still being rebuilt, I talk about that district behind the Shinjuku station that was struck by the defeat of the war. I loved that kind of district. I remember wandering around in abandoned and forgotten places that weren’t yet rebuilt. I was often going to those districts after school.

Hervé De la Haye: Does your Bande Dessinée only talk about your childhood, or are you also talking about your career in animation?

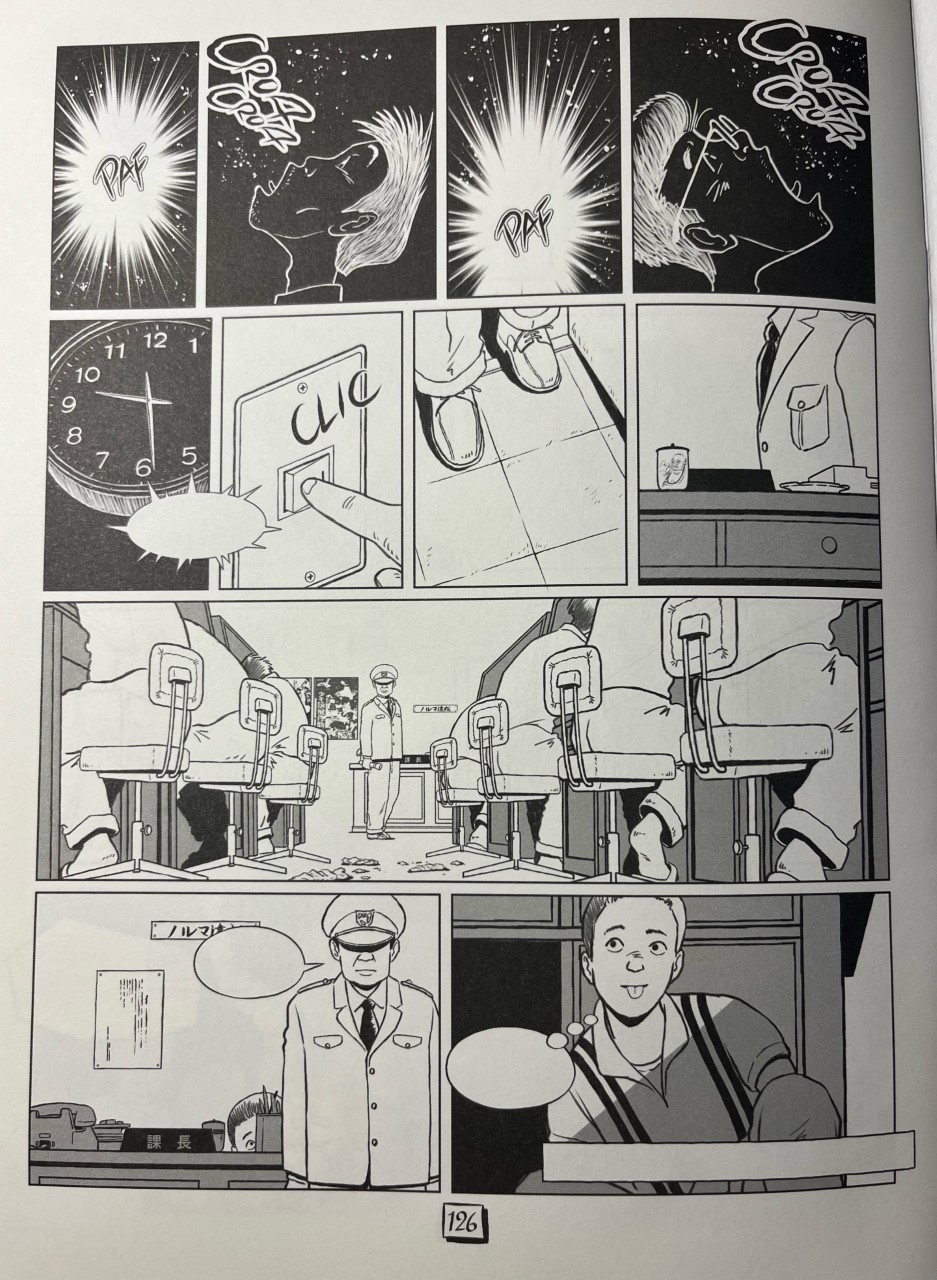

Rintarô: Obviously, I talk a lot about my professional life. I talk about Metropolis and other stuff, of course. But my life is 81 years long; thus, I cannot tell everything. I try to talk a bit about everything. Look, here I talk about Harlock, then Galaxy Express, Genma Wars, and here we see the musician Keith Emerson whom I worked with on Genma Wars. There was also the period when I worked on Manie-Manie, in which Otomo worked as a director. It will be about 250 pages long.

Hervé De la Haye: This Bande Dessinée will be published in Japan, I guess? Do you know if it will be published in France?

Rintarô: At the moment, I do not intend to publish it in Japan because I made this Bande Dessinée for my French friends that wanted to know more about that history. It is, first and foremost, a French release.

[Rintarô thanks Les Utopiales and the public] The movie Galaxy Express 999 that you’re going to watch is a film I made 40 years ago. At the time, I was around 40 years old, and that was my first animated feature film. You’re going to watch the 1980 version. At the time, it was made with 35mm film, and I realize now that in those 35mm films, a vast amount of detailed info, images, and sounds, were kept and contained. Those pieces of information fell asleep for over 40 years, but thanks to technological progress, we could resurrect them in this 4K remaster. I hope that you will enjoy discovering that movie with that remaster. Before making Galaxy Express, I directed a TV series called Harlock. Therefore Toei came to me to make that movie, and I’m truly thankful for that. Since that was the first time I directed a long animated feature film, I didn’t know where to begin; therefore, I told myself I’d continue working just like I did for Harlock. Thus I’ll use the same kind of rhythm. I identified myself a bit with the character of Harlock. Music is extremely important to me while making a movie or a TV series, and I was certain of my musical choice here. Galaxy Express 999 is a bit like a road movie. Making that movie, I felt like I was riding that train, and I’m sure you’ll feel the same in that theater room.

In my lifetime, I made numerous on-stage presentations like this one, but I have never felt such warmth from the audience. I was even requested to dance tonight! Thank you! Tonight, you will be watching three movies: Adieu Galaxy Express 999, Metropolis, and Manie-Manie.

Just now, many hands were raised to indicate that you had seen Adieu Galaxy Express 999, so I will speak briefly about it. Since Galaxy Express 999 was so successful, the producer requested I also work on a sequel. But, I was pretty hesitant because I had already given it my all on the first movie. However, the producer resolutely ignored my rejection. It came to a point where he would chase me around Shinjuku Station in Tokyo. [He starts running to the other side of the stage] He even threatened to stay in front of my house! Having him roaming around my home for hours was not something I wanted at all… I could also understand his desire to keep me because Galaxy Express 999 was a massive hit. I ended up accepting it under the condition that the team would have to be the same as the first movie.

We previously learned that some audience members did not see Galaxy Express 999. I will be spoiling the end of the movie, sorry. In the final scene, two characters, Tetsuro and Maetel, are seen kissing. Everyone expected the continuation of their romance, but it didn’t happen. With the scenarist, we hesitated a lot on the kind of narration we wanted for Adieu Galaxy Express 999. Eventually, we agreed that we would completely change the direction and the style, and we settled for the theme of war and combat. I, personally, am not too fond of war-themed animated movies. I believe animation is not fit to capture the essence of war. But we wanted to avoid making a sequel solely about the happily ever after of these characters, hence the theme. I must say, it was quite arduous to approach this movie from this angle; that’s why I added a touch of fantasy.

After the redaction of the scenario, I went on with the conception of the storyboard. While I was making it, in order to portray war, I immediately thought of Andrzej Wajda’s cinema. Andrzej Wajda is a polish director whose wife was a fighter. He directed movies that portrayed resistants purchased by nazis. His works had a realistic outlook and astounding rhythm. As you will see during the projection, I wanted to pay a great tribute to him. For those who have seen Galaxy Express 999 and its sequel, you will notice that the styles are very different. There’s nothing in common in the editing. The transitions in the first movie are very soft, while they are aggressive and rhythmic in the sequel. And, you have to understand that when a director makes those, each shot and transition has a meaning. It requires a joint effort from everyone; the whole artistic team and the director. And that goes for all kinds of movies: thrillers, melodrama, war movies, etc. For instance, if I want to film my interpreter Shoko, I could position my camera in thousands of ways. [Rintarô goes next to Shoko] To choose the camera’s angle, we must reflect on the intention. Do I want to capture her face? [points to her face] Her breasts? [points to her breasts] It vastly depends on the moment in the movie. You need to put a lot of thought behind each shot to pick the right camera angle.

For instance, Jean Renoir’s transitions are very soft, but they fit entirely with what he wants to express. His style allows the spectator to smoothly get pulled into the movie’s universe. Other directors may prefer more stylized and aggressive transitions, which create some sort of conflict. A good illustration of this would be Hitchcock. He believed that when an image was introduced from the left – i.e., the same side as the heart – the perception of said image would be natural. Meanwhile, if an image were to be introduced from the opposite side, it would create an unsettling feeling. So, if someone were to shoot me from this side [points to the left], it would seem more normal to you, the spectator. But if they were to shoot me from this side [points to the right], it would feel stranger and throw the audience off. And that is the result he wanted to achieve. In my opinion, Hitchcock is the true king of cinema and editing. He studied psychiatry a lot, and each of his shots was created from the perspective of a psychiatrist. In a nutshell, each story requires a specific form.

The third film you will watch is an omnibus called Manie-Manie, composed of three short films. One of them was directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, and that was the first movie he directed. The movie’s duration is 1h05, and we took two years to make those films. The three directors, Otomo, Yoshiaki Kawajiri, and I, truly made what we wanted to make. Each narration calls for a different type of transition, and each director has their own style. The short film I made is called Labyrinth Labyrinthos. I wanted to bring to the screen a memory of my childhood when I was playing in small alleys where I was sensing a fantastic atmosphere. There is one person in France that said that he loved that movie and especially Labyrinth Labyrinthos. This person is Marc Caro, the co-director of Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children. You’re here with us at the back of the room. Can you stand? [The whole room claps] I already came to France quite a few times to see my friends like Shoko here, but I have never met Marc before. It’s the first time I met him here in Nantes. We’re going to talk tomorrow, and Shoko always says she’s terrified of meetings like these because interpreting two crazy men simultaneously is impossible! [The whole room laughs] So I told Shoko she could run away if she couldn’t handle it anymore! Because otherwise, she could burst into tears! [The whole room laughs] I don’t know how it’s going to happen, but in any case, I’m thrilled to be able to meet Marc Caro. I hope you’ll appreciate Manie-Manie! Thanks a lot and now I’ll dance! [The whole room claps, and Rintarô starts dancing and posing for photos]

Thanks for coming in such numbers this morning. If you’re getting up this early to see my movies, that means you are my friend. Today is the last day of Les Utopiales, and I’m a bit sad! But I’m really happy that the screening of Harlock‘s episode 34 this morning was in its original version with the sound and music we created, especially the ocarina music that represented the fragility of the lone wolf that is Harlock. But let’s talk about Genma Wars. It’s an extremely important movie to me. It’s a movie that revolutionized the style of Japanese animation. Before Genma Wars, animated movies were mostly produced by movie-producing companies. Still, Haruki Kadokawa, the president of the Kadokawa publishing company, came in and asked me to make that movie. It was the first time a publishing company was producing an anime movie. Since the production form was different, I also wanted to change many things we typically do in anime in that movie. I wanted to try new things, especially in terms of character design. That’s why I asked Katsuhiro Otomo to make the character design. He was a mangaka and had never worked in cinema before, so I invited him to a cafe, and for 3 hours I explained why I wanted to work with him. I told him that I couldn’t make that movie without his drawings. He was a mangaka, but while talking with him, I immediately understood that he was a big cinephile. During that meeting, he told me he wasn’t sure his drawings could work in animation. Those who read his manga can understand what he meant; it’s very difficult to animate his characters. I reassured him, telling him that yes, it would be difficult, but I knew it was possible, and I would bring the best animators ever. I wanted to try things that had never been done before in animation. For example, before Genma Wars, anime was mostly set in imaginary worlds, but I wanted it to be set in existing places with a highly realistic touch for the backgrounds. Before Genma Wars, shoes in anime were just simple shoes, but I wanted to show precise shoes of a specific brand and design. [Rintarô is asked a question about his relationship with Otomo and the cycling short film he made with him] I met Otomo thanks to Genma Wars, but after that, since he was also a cinephile, we got along quickly. Thus, one day, I offered him to direct his first film, which is the short film that is part of Manie-Manie. With this, he learned the whole process of animation making, and that’s how he then directed the movie Akira which you must know. Speaking of the short film 48×61, which shows us two riding our bicycles, we made that because we’re both very big fans of the Tour de France. We both agreed that once we stopped working, we’d become cyclists to participate in the Tour de France.

A few more pages from Rintarô’s Bande Dessinée project.

We wish to express our heartfelt gratitude towards Mr. Rintarô, Ms. Shoko Takahashi, Rintarô’s interpreter and personal friend, as well as the staff from the International Science Fiction Festival Les Utopiales which made this encounter possible. Our thanks especially go towards Ms. Estelle Lacaud and Mr. Frédéric Temps.

Transcript and translation from French by Arnaud Bastié and Sarah Pho. Edited by Dimitri Seraki.

Like our content? Help us make more by supporting us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Colors and cinematography in anime – Interview with Death Note director Tetsurô Araki

As the director of cult works such as Death Note, Highschool of the Dead, and Attack on Titan seasons 1 to 3, Tetsurô Araki is one of the biggest names in the anime industry. In recent years, he has had many occasions to get his name out, from the movie Bubble to...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks