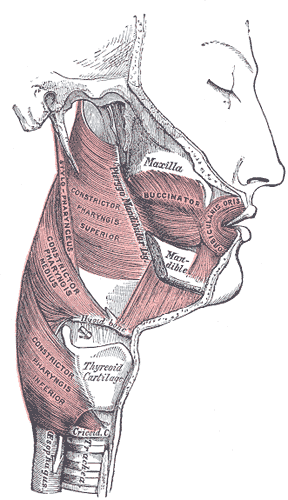

The buccal space (also termed the buccinator space) is a fascial space of the head and neck (sometimes also termed fascial tissue spaces or tissue spaces). It is a potential space in the cheek, and is paired on each side. The buccal space is superficial to the buccinator muscle and deep to the platysma muscle and the skin. The buccal space is part of the subcutaneous space, which is continuous from head to toe.[1]

| Buccal space | |

|---|---|

The buccal space is located superficial to buccinator muscle. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Structure

editBoundaries

editThe boundaries of each buccal space are:

- the angle of the mouth anteriorly,[1]

- the masseter muscle posteriorly,[1]

- the zygomatic process of the maxilla and the zygomaticus muscles superiorly,

- the depressor anguli oris muscle and the attachment of the deep fascia to the mandible inferiorly,

- the buccinator muscle medially (the buccal space is superficial to the buccinator),[1]

- the platysma muscle, subcutaneous tissue and skin laterally (the space is deep to platysma).[1]

Communications

edit- to the pterygomandibular space, infratemporal space, submasseteric space or even to the lateral pharyngeal space posteriorly,

- to the infraorbital (canine) space superiorly.[1]

Function

editContents

editIn health, the space contains:

- the buccal fat pad,[1]

- the parotid duct (Stensen duct),[1]

- the anterior facial artery and vein,[1]

- the transverse facial artery and vein.[1]

Clinical significance

editA hematoma may create the buccal space, e.g. due to hemorrhage following wisdom teeth surgery. Buccal space abscesses typically cause a facial swelling over the cheek that may extend from the zygomatic arch above to the inferior border of the mandible below, and from the anterior border the masseter muscle posteriorly to the angle of the mouth anteriorly.[1] Unless another space is also involved, the tissues around the eye are not swollen. It is usually treated by surgical incision and drainage, and the incision is located inside the mouth to avoid a scar on the face.[2] The incision are placed below the parotid papilla to avoid damage to the duct, and forceps are used to divide buccinator and insert a surgical drain into the buccal space. The drain is kept in place for a variable period of time following the procedure.

Long standing buccal abscesses tend to spontaneously drain via a cutaneous sinus at the inferior of the space, near the inferior border of the mandible and the angle of the mouth.[1] An untreated cutaneous sinus can cause disfiguring soft tissue fibrosis, and the tract can become epithelial lined.[3]

Odontogenic infections

editSometimes the buccal space is reported to be the most commonly involved fascial space by dental abscesses,[2] although other sources report it is the submandibular space.[1] Infections originating in either maxillary or mandibular teeth can spread into the buccal space, usually maxillary molars (most commonly) and premolars or mandibular premolars.[1] Odontogenic infections which erode through the buccal cortical plate of the mandible or maxilla will either spread into the buccal vestibule (sulcus) and drain intra-orally, or into the buccal space, depending upon the level of the perforation in relation to the attachment of buccinator to the maxilla above and the mandible below (see diagrams). Frequently infection spreads in both directions as the buccinator is only a partial barrier.[3] Infections associated with mandibular teeth with apices at a level inferior to the attachment, and maxillary teeth with apices at a level superior to the attachment are more likely to drain into the buccal space.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 317–333. ISBN 9780323049030.

- ^ a b Kerawala C, Newlands C (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 374–375. ISBN 9780199204830.

- ^ a b Wray D, Stenhouse D, Lee D, Clark AJ (2003). Textbook of general and oral surgery. Edinburgh [etc.]: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 263–267. ISBN 0443070830.