G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero is a comic book that was published by Marvel Comics from 1982 to 1994. Based on Hasbro's G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero line of military-themed toys, the series has been credited for making G.I. Joe into a pop-culture phenomenon.[1] G.I. Joe was also the first comic book to be advertised on television, in what has been called a "historically crucial moment in media convergence".[2]

| G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero | |

|---|---|

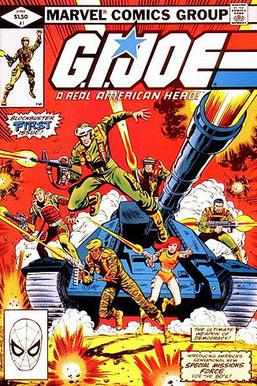

Cover to G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #1. Art by Herb Trimpe. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | Military |

| Publication date | June 1982 – December 1994 |

| No. of issues | 155 |

| Main character(s) | See List of G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero characters |

| Creative team | |

| Written by | Larry Hama, Herb Trimpe, Steven Grant, Eric Fein, Peter Quinones |

| Penciller(s) | Herb Trimpe, Don Perlin, Mike Vosburg, Larry Hama, Russ Heath, Frank Springer, Marie Severin, Rod Whigham, Todd McFarlane, Marshall Rogers, Ron Wagner, Paul Ryan, Tony Salmons, M. D. Bright, Geof Isherwood, Lee Weeks, John Statema, Ron Garney, Andrew Wildman, Chris Batista, Phil Gosier |

| Inker(s) | Bob McLeod, Jack Abel, Jon D'Agostino, Chic Stone, Herb Trimpe, Steve Leialoha, Russ Heath, Andy Mushynsky, Keith Williams, Randy Emberlin, Fred Fredericks, Tom Palmer, Stephen Baskerville, Chip Wallace, Scott Koblish |

The series was written for most of its 155-issue run by comic book writer, artist, and editor Larry Hama, and was notable for its realistic, character-based storytelling style, unusual for a toy comic at the time. Hama wrote the series spontaneously, never knowing how a story would end until it was finished, but worked closely with the artists, giving them sketches of the characters and major scenes. While most stories involved the G.I. Joe Team battling against the forces of Cobra Command, an evil terrorist organization, many also focused on the relationships and background stories of the characters. Hama created most characters in collaboration with Hasbro, and used a system of file cards to keep track of the personalities and fictional histories of his characters, which later became a major selling point for the action figure line.

G.I. Joe was Marvel's top-selling subscription title in 1985, and was receiving 1200 fan letters per week by 1987. The series has been credited with bringing in a new generation of comic book readers, since many children were introduced to the comic book medium through G.I. Joe, and later went on to read other comics.[3] The comic book has been re-printed several times, and also translated in multiple languages. In addition to direct spin-offs of the comic book, several revivals and reboots have been published throughout the 2000s.

Publication history

editBackground

editIn the early 1980s, Hasbro noted the success of Kenner Products' Star Wars action figures, and decided to re-launch its long-running G.I. Joe property as G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero with 3.75 inches (9.5 cm) scale action figures rather than the traditional 12 inches (30 cm) scale. Hasbro also decided that it wanted the new figures to have a back story.[4] In 1981, Hasbro CEO Stephen Hassenfeld and Marvel Comics President Jim Galton met by coincidence at a charity fundraiser and Hassenfeld shared Hasbro's plans for the G.I. Joe relaunch. Galton offered Marvel's services as creative consultants, and Hassenfeld agreed to allow Marvel attempt to design a concept for G.I. Joe.[5]

Coincidentally Larry Hama, then an editor at Marvel, had begun to design characters and background for a series concept he was pitching that would be entitled Fury Force, about a team of futuristic super-soldiers affiliated with S.H.I.E.L.D., an existing Marvel Universe property combining military and science fiction genre elements.[4][6] As Hama tells it, he got the job of writing for the series because Marvel had asked every other available creator to write it and no one else would.[7] Unable to find other writing work, he later said that, "if they had asked me to write Barbie, I would have done that, too".[8]

Soon after this, Hasbro hosted a meeting with Hama, Jim Shooter, Tom DeFalco, Archie Goodwin, and Nelson Yomtov to discuss the future of the property. It was at this meeting that Goodwin suggested the idea of Cobra Command as a recurring enemy for G.I. Joe to fight (similar to the HYDRA terrorist organization - recurring enemies to the aforementioned S.H.I.E.L.D. organization). Prior to this, Hasbro had not considered giving G.I. Joe an enemy.[9] Based on the results of this meeting, Hasbro contracted Marvel to produce a comic book series featuring the toys.

Early development

editThe first issue was published in June 1982, containing two stories, both of which were written by Hama. The first story, "Operation: Lady Doomsday", was drawn by Herb Trimpe, who drew most of the early issues and also wrote issue #9, and the second story, "Hot Potato", was drawn by Don Perlin.[10] This issue introduced many basic concepts of the G.I. Joe universe, such as the Joes having a base under a motor pool, and introduced the iconic "original 13" G.I. Joe Team members. The issue also introduced two recurring villains, Cobra Commander and the Baroness. Whereas Cobra Commander and the various Joes already had action figures issued, the Baroness is the earliest example of a G.I. Joe character whose first appearance in the comics predated the conception of its action figure.[8][11]

Most of the early stories were completed in one issue, but multi-part stories began to appear by the middle of the series' first year of publication,[12] and there were hints of the ongoing storylines that would later characterize the series. In May 1983, issue #11 introduced many new characters, including most of the 1983 action figure line and the villain Destro, who would become a frequently recurring character. Many subsequent storylines involved the machinations and power struggles between him, Cobra Commander, and the Baroness. Issue #11 established a pattern for the series in which every so often Marvel would publish an issue introducing a group of characters and vehicles that represented the new year's toy offerings.[13]

An early highlight was 1984's "Snake Eyes: The Origin" Parts I & II, published in issues #26-27. This issue established Snake Eyes' complicated background, and tied his character into many other characters, both G.I. Joe and Cobra. Hama considers it to be his favorite storyline from the Marvel run.[14] In 1986, echoing events portrayed in the TV series, G.I. Joe #49 was published, introducing the character of Serpentor, a genetically created amalgam of history's greatest warriors. Serpentor played a significant role in the Cobra Civil War, which occurred in issues #73-76, a landmark story event that involved nearly every G.I. Joe and Cobra character vying for control of Cobra Island.

Later years and cancellation

editWhen G.I. Joe began, most toy tie-in comics lasted an average of two years,[15] so G.I. Joe, lasting for 12 years, was considered a runaway success. Through the years, the comic book series chronicled the adventures of G.I. Joe and Cobra, using a consistent storyline.[16] In the early 1990s, however, it began to drop in quality, and was canceled by Marvel in 1994 with issue #155 due to low sales.[15] Hasbro canceled the A Real American Hero toy line in the same year. Between the lack of new toys and the cancellation of the second TV series three years earlier, the comic book could not count on the same cross-platform support it had enjoyed in the past. The target demographic had also changed considerably. According to Hama:

It reached the end of its half-life. Until G.I. Joe and Transformers, toy books had a life expectancy of 1-2 years – 3 years was considered a long time. Hasbro didn’t expect the toy-line to have that much life in it. Also, the market had changed completely. When I first started doing store signings, there were lines around the block and it was all 10-year-old boys. The last time I did a story signing in New York City, everybody was over 30, and two of the guys who showed up were mailmen who had skipped off their routes to get their books signed.[17]

The final issue featured a stand-alone story titled "A Letter from Snake Eyes". Narrating from his perspective, Snake Eyes tells his story through recollections of his many comrades-in-arms who have died over the years.[18]

Shortly after the final issue, G.I. Joe Special #1 was released in February 1995, containing alternate art for issue #61 by Todd McFarlane. McFarlane was the original penciller for issue #61, but his artwork had been rejected by Larry Hama as unacceptable, and so Marshall Rogers was brought in to pencil the final published version. In the years following, McFarlane became a superstar comic artist, and Marvel eventually decided to print the unpublished work.[19]

Promotion

editHasbro used television advertising to publicize the series, and when the first one aired in 1982 featuring G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #1, it was the first time a commercial had ever been used to promote a comic book.[20] Since the commercials were technically promoting the comic books rather than the toys, they allowed Hasbro to circumvent television regulations mandating that toy commercials could not contain more than ten seconds of animation.[2] By not showcasing any characters and toys outside of the comic book context, they were able to include a full thirty seconds of animation.[17] Marvel was paid $5 million by Hasbro to produce the commercials through its animation division Marvel Productions.[2] Larry Hama relates the genesis of the commercials:

There were only a few seconds of animation you could have in a toy commercial, and you had to show the toy, so people wouldn’t get totally deluded. Somebody at Hasbro (who was actually sort of a genius) named Bob Pruprish, realized that a comic book was protected under the first amendment, and there couldn't be restrictions based on how you advertised for a publication.[11]

Between the toy line, comic books, commercials and subsequent cartoon series, Hasbro's marketing plan was highly successful and eventually became an industry standard, an early example of a practice that would years later be described by Jenkins as a "transmedia narrative".[21][22] Although the adolescent male demographic was the traditional comic book reader, an unintended result of the TV advertising tie-ins was that they attracted people who were not traditional comic book readers. In an interview, Hama stated:

I think [the commercials have] also opened it up to a very different type of audience. I get a lot of letters from girls. I get a lot of letters from young housewives who sort of started watching the cartoons with their kids and sort of started getting into the characters, and then somewhere along the line they picked up the comic book and they started following the stories and got caught up in the continuity.[9]

The comic book's popularity with women has also been attributed to the strong female characters featured in the comic, such as Scarlett and Lady Jaye. Since very few of the G.I. Joe action figures were female, Hama tended to frequently use all of the female characters, including those that were created as recurring characters in the comics.[14]

Writing style

editMany readers praised the series for its attention to detail and realism in the area of military tactics and procedures. Much of this was due to Hama's military experience (he was drafted into the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers during the Vietnam war), but he also did a large amount of research in order to be as up-to-date as possible. He frequented Sky Books, a military-oriented bookstore in New York, and read many U.S. Army field manuals and technical manuals, and also credits his friend Lee Russel, a military historian, for helping him with research.[9]

In style and plot structure, the comic often made use of overlapping story threads. According to Hama:

We’ve been following one basic storyline pretty much in the comic for fifty issues. It’s sort of like an extended soap opera, although I try to have a real solid resolution at the end of each book. But I like to keep some plot threads going. There's a sort of episodic quality to some of the earlier books, like one episode will last six issues. That will resolve completely, but two issues into it another thread may have started. At any given time there’s probably about three overlapping threads.[9]

The story arcs coincided with each of the new lines of G.I. Joe toys that Hasbro was producing, however the comic book was not directly influenced by the toy products. Of the Hasbro/Marvel relationship, Hama observed that the toy company did not demand the book to be written a certain way:

We're the final word on what happens with the book. Hasbro has been extremely open about it, [and] I don't write this as a kiddie book. I don't write G.I. Joe any differently from the way I write Wolverine.[16]

Hama wrote out page-by-page plots for all of the issues he wrote, with most pages having four to six panels. He worked very closely with the artists in plotting the book,[9] and wrote the series spontaneously, never knowing how an issue would end until he got to the last page.[8]

Characterization

editIn the first issue, it is revealed that the team’s official moniker is Special Counter-Terrorist Unit Delta. G.I. Joe featured an ensemble cast, with the original thirteen characters being Hawk, Stalker, Breaker, Clutch, Scarlett, Snake Eyes, Rock ‘n Roll, Steeler, Grand Slam, Flash, Short-Fuze, Grunt, and Zap. This reflected their origins in the Hasbro toy line, with the initial characters being the same as the action figures in the original 1982 release of the toy line.[23] The team roster expanded as additional action figures were released.

Hama created most characters in collaboration with Hasbro. Hasbro would send him character sketches and brief descriptions of each character's military specialties, and Hama would create detailed dossiers on each characters, giving them distinct personalities and background stories. Hama kept track of each character on file cards, and eventually Hasbro decided to reprint shortened versions of these dossiers as file cards on the packaging for the action figures.[24] The file cards themselves became a selling point for the toy line, and appealed to both children and adults. Hama noted that:

... it has to be read on two levels ... A ten-year-old kid has to be able to read it and think it's absolutely straight [but] there should be a joke in there for the adult. One of the factors that helped sell G.I. Joe [figures] was that the salesmen who sold it to retailers used the dossiers as a selling point.[11]

Hama tended to base the personalities of the characters on people that he knew, and he credits this technique for the realism of his characterization.[8] He later said that "events and continuity never meant anything to me. The important thing was the characters".[25]

Reception

editInitially, the response to the new comic book was muted due to its low status as a "toy book". However its popularity eventually grew, and is credited with bringing in a new generation of comic readers.[17] Within two months of the toy line's launch, "some 20 per cent of boys from ages five to twelve had two or more G.I. Joe toys",[26] and by 1988/89 a survey conducted by Hasbro found that "two out of every three boys between the ages of five and eleven owned at least one G.I. Joe figure".[27] These boys were drawn to the G.I. Joe comic book through its association with the toy line, and then went on to other comics.[3] As Hama puts it:

It was a toy book. Very uncool to the fan-boys at the time. It never got reviewed in the fan press. Totally ignored. The kids who bought G.I. Joe were a totally new crowd who were coming into the comic shops for the first time because they had the toys and they saw the commercials. Many of them started to buy other comics while they were there.[17]

According to comic book historian John Jackson Miller, Hasbro's promotion of the comic resulted in dramatic sales increases, from 157,920 copies per month in 1983 to 331,475 copies per month in 1985, making it one of Marvel's "strongest titles".[28] According to Jim Shooter, G.I. Joe was Marvel's number one subscription title in 1985.[5] By 1987, the main title was getting 1200 letters every week.[9] Hama read every one, and sent out fifty to one hundred hand-written replies every week.[29]

In comics, where images are at least half the language, pictures can form valid narrative as easily and functionally as words – and, at times, without them ... such as the lauded GI. Joe [sic] "Silent Interlude" #21. It does at least prove, as if there were any doubt, the viability of visual narrative.

— A. David Lewis, The shape of comic book reading[30]

An early issue that attracted much attention, both positive and negative, was G.I. Joe #21, titled "Silent Interlude", which was told entirely without words or sound effects. In a 1987 interview, Hama explained that the motivation for the story was that he "... wanted to see if [he] could do a story that was a real, complete story - beginning, middle, end, conflict, characterization, action, solid resolution—without balloons or captions or sound effects".[9][31] At first, the issue was controversial; some readers felt cheated that it had no words and could be "read" so quickly,[14] but it eventually became one of the series' most enduring and influential issues.[32][33] Issue #21 has been recognized as a modern comic classic,[6] and has become a prime example of comics' visual storytelling power. Comic book artist and theorist Scott McCloud (author of Understanding Comics) describes "Silent Interlude" as "... a kind of watershed moment for cartoonists of [our] generation. Everyone remembers it. All these things came out of it. It was like 9/11".[32] The issue would eventually be ranked #44 in Wizard Magazine's listing of the "100 Best Single Issues Since You Were Born",[34] and #6 on io9's "10 Issues of Ongoing Comics that Prove Single Issues Can Be Great".[35]

Spin-offs

editIn 1985, G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero spawned an annual publication called G.I. Joe: Yearbook. G.I. Joe: Yearbook differed from the typical comic book annual publication in that it was more like a magazine. Each issue contained articles about the animated TV program, a summary of the comic book's plot to date, and one or two original stories written by Larry Hama. G.I. Joe: Yearbook ran until 1988.[36]

In 1986, the success of A Real American Hero lead Marvel to produce a second title: G.I. Joe: Special Missions which lasted 28 issues.[37] Herb Trimpe was the artist for most of the run, with Dave Cockrum providing pencils on several issues. Spinning out of G.I. Joe #50 and set in the same continuity,[38] the series presented more intense violence and a more ambiguous morality than the main title, and the Joes faced enemies who were not related to Cobra.[39] Each issue usually featured a stand-alone mission focusing on a small group of Joes.[40]

Two mini-series were also produced. The first, G.I. Joe: Order of Battle, was a 4-issue mini-series running from December 1986 to March 1987, reprinting the data found on the action figures' file cards with some edits. Written by Hama, with all-new artwork by Trimpe, the first two issues featured G.I. Joe members, while the third issue focused on the members of Cobra Command, and the fourth highlighted the vehicles and equipment used by both organizations. A trade-paperback edition, which included material from all four issues, was published in 1987.[41]

The second, G.I. Joe and the Transformers, was a 4-issue mini-series running from January to April 1987. The story had the Joes and the Autobots joining forces to stop the Decepticons and Cobra from destroying the world.[38] A trade paperback later collected all four issues.[42]

Reprints and revivals

editThe first 37 issues of the main series were released in 13 digests titled G.I. Joe Comic Magazine. Subsequently, Tales of G.I. Joe reprinted the first fifteen issues of G.I. Joe on a higher quality paper stock than that used for the main comic. Four Yearbooks (1985–1988) also collected some previous stories, summarized events, and published new stories that tied into the main title, aside from the first Yearbook, which re-printed the seminal first issue. The series was also translated into several languages, including German, Spanish, Portuguese, Polish, French (Canada), Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Danish, Japanese, Arabic, and Indonesian.[43]

G.I. Joe European Missions was published monthly from June 1988 until August 1989. The European Missions series are all reprints of Action Force Monthly, which was published in the UK.[44] Unlike the weekly Action Force series, these were all original stories, never before seen in the U.S. They were not written by Larry Hama.

In July 2001, Devil's Due Publishing acquired the rights to G.I. Joe and began publication of G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero Vol. 2. Originally intended to be a four-issue limited series, strong sales led to it being upgraded to ongoing, and it lasted for 43 issues, before being relaunched as a new series G.I. Joe: America's Elite, which lasted for 36 issues. Devil's Due's license with Hasbro expired in 2008 and was not renewed.[45]

Building on the success of the Devil's Due Comics run of G.I. Joe, Marvel Comics collected the first 50 issues in five trade paperbacks, with ten issues in each book. The trade paperbacks each featured a new cover artwork drawn by J. Scott Campbell.[38]

In 2009, IDW Publishing began to re-publish the original series again as Classic G.I. Joe, and like Marvel before it, collects ten issues in each volume; the last few collections have slightly more issues in order to conclude with the 15th paperback volume, which was published in August, 2012. Other collections for the spin-off Special Missions and assorted Annuals also appeared. In November 2012, IDW restarted its reprint series with the hardcover G.I. JOE: The Complete Collection, Vol. 1, intending to reprint all the stories in reading order.

IDW also revived the original G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero continuity, as an ongoing series in 2010, with a special #155½ issue released on Free Comic Book Day. Following with issue #156 onwards in July 2010 with every issue in the series written by Larry Hama, this lasted until December 2022, concluding with issue 300.[7][46] The series resumed once again with issue #301 under new license holder Skybound Entertainment in November 2023.[47]

References

edit- ^ James Wortman (August 5, 2009). "Larry Hama and the Not-So-Average Joes". Broken Frontier. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Derek Johnson (May 8, 2008). ""The Legend of G.I. Joe…New from Marvel Comics!": The Toy as Comic Book on Television". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Jim Shooter (22 November 2011). "Comic Book Distribution - Part 3". Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b Ben Smith. "1980's G.I. Joe Team Origins & Artwork Uncovered". Metropolis Comics. Archived from the original on October 29, 2005. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Jim Shooter (6 July 2011). "The Secret Parts of the Origin of G.I. JOE". Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b Brian Cronin (January 5, 2006). "Comic Book Urban Legends Revealed #32". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 31, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Truitt, Brian (April 14, 2010). "Larry Hama relaunches his '80s 'G.I. Joe series". USA Today. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Bill Mitchel (June 3, 2009). "IN-DEPTH: LARRY HAMA ON G.I. JOE, THE 'NAM & MORE". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zimmerman, Dwight Jon (July 1986). "Larry Hama". David Anthony Kraft's Comics Interview (37). Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive Q & A with Mark Bellomo, author of the Ultimate Guide to G.I. Joe". General's Joes. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Irving, Christopher (June 2006). "The swivel-arm battle-grip revolution: How G.I. Joe recruited a new generation of comic-book readers". The Ultimate Comics Experience (16): 15–31.

- ^ The first multi-part story was in G.I. Joe #6 (December 1982) and #7 (January 1983),

- ^ c.f. G.I. Joe #11 (May 1983), #44 (February 1986), #60 (June 1987), #68 (February 1988) #82 (January 1989)

- ^ a b c Meyer, Fred. "JBL Interview with Larry Hama". Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ a b Yojoe.com (December 1997). "Interview with Larry Hama". Yojoe.com. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ a b Santelmo, Vincent (1994). The Official 30th Anniversary Salute To G.I. Joe 1964–1994. Krause Publications. p. 159. ISBN 0-87341-301-6.

- ^ a b c d Kurt Anthony Krug (July 1, 2009). "Interview: G.I. JOE Generalissimo Larry Hama". Mania.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Norlund, Christopher (Summer 2006). "Imagining Terrorists before Sept. 11: Marvel's G.I. Joe Comic Books, 1982–1994". ImageText: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. 3 (1). Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (November 20, 2008). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #182". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Tomio, Jay. "Comic Book Review – G.I. Joe #0 (IDW)". Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4281-5.

- ^ Bainbridge, Jason (December 2010). "Fully articulated: The rise of the action figure and the changing face of 'children's' entertainment". Continuum. 24 (6): 829–842. doi:10.1080/10304312.2010.510592. S2CID 144221547.

- ^ Hama, Larry. G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero, vol. 1, issue no. 1, Cover date: June 1982. Marvel Comics.

- ^ Epstein, Dan. "Larry Hama Interview". Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Steve Ekstrom (2008-09-12). "G.I. Joe Roundtable, Part 1: Hama, Dixon, Gage & More". Newsarama. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Kline, Stephen (1995). Out of the garden: toys, TV, and children's culture in the age of marketing. Verso. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-85984-059-7. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Santelmo, Vincent (2001). The complete encyclopedia to G.I. Joe (3rd ed.). New York: Krause. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-87341-874-4.

- ^ John Jackson Miller (30 April 2009). "Toys, comics, and irony: Hasbro's TV network". Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Fred Meyer (March 19, 2007). "JoeBattlelines: Larry Hama Interview". JoeBattlelines. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Lewis, A. David (2010). "The shape of comic book reading". Studies in Comics. 1 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1386/stic.1.1.71/1.

- ^ Kushner, Seth. "For the Love of Comics #08: Enjoy the Silence". Graphic NYC. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Shaenon K. Garrity (18 September 2009). "All The Comics in the World: "Silent Interlude"". comiXology. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse. "G.I. Joe: Origins #19 Review - Larry Hama returns for another silent adventure with Snake Eyes". IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Staff (May 2006). "100 Best Single Issues Since You Were Born". Wizard: The Magazine of Comics, Entertainment and Pop Culture. pp. 86–101.

- ^ Keith Veronese (9 November 2011). "10 Issue of Ongoing Comics That Prove Single Issues Can Be Great". io9. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "G.I. Joe Comic Book Archive: The Yearbooks". Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Jay Tomio (25 October 2009). "G.I. Joe – Classic Reread: Special Missions 'Best Defense'". Boomtron. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Weiner, Robert G. (2008). Marvel graphic novels and related publications: an annotated guide to comics. New York: McFarland. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0-7864-2500-6.

- ^ Dave Richards (17 January 2006). "I'll Take Manhattan: Moore and O'Sullivan talk "G.I. Joe: Special Mission: Manhattan"". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Jay Tomio (2 December 2008). "On the Spot at BSC - Chuck Dixon Interview". Boomtron. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Hama, Larry; Herb Trimpe; Jack Abel; et al. (1987). G.I. Joe: Order of Battle Volume 1. Marvel. ISBN 978-0-87135-288-0.

- ^ Higgins, Michael; Herb Trimpe; Vince Colletta; et al. G.I. Joe and the Transformers (Trade paperback). Marvel (1993). ISBN 978-0-87135-973-5.

- ^ G.I. Joe Pasukan Elite Amerika #10. Indonesia: P.T. Misurind. 1990.

- ^ Maggie Thompson; Brent Frankenhoff; Peter Bickford (2010). Comics Shop. Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-4402-1283-3.

- ^ "Devil's Due Loses G.I. Joe Comic Book License". IESB.net. 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009.

- ^ "FCBD 2010: Exclusive Interview With G.I. JOE: A Real American Hero #155 ½'S Andy Schmidt". Freecomicbookday.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ Salmon, Will (June 15, 2023). "Long-running G.I. Joe comic A Real American Hero returns for a new run at Skybound". GamesRadar+. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

External links

edit- G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero series archive at YoJoe.com

- G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero series archive at JMM's G.I. Joe Comics Homepage