Fort Cépérou

| Fort Cépérou | |

|---|---|

| Cayenne, French Guiana in French Guiana | |

Remains of the fort | |

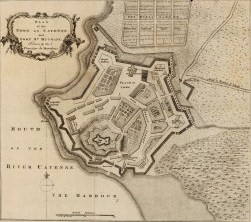

1760 map of fortifications of Cayenne. Fort Cépérou rises above the NW walls along the river, lower right in this map. | |

| Coordinates | 4°56′15″N 52°20′13″W / 4.937630°N 52.336843°W |

Fort Cépérou was a fort that protected the city of Cayenne, French Guiana. It is named after Cépérou, a celebrated indigenous chief who ceded the land.[1]

The original wooden fort was built on a hill looking over the mouth of the Cayenne River in 1643. Over the years that followed the French temporarily lost the site to the Dutch, English and Portuguese. The fort was torn down and rebuilt several times.

Between 1689 and 1693 the whole town of Cayenne, including the fort, was surrounded by a classic line of fortifications by Vauban. The town was occupied by the Portuguese during the Napoleonic wars between 1809 and 1817 and Vauban's fortifications were destroyed, as were the bastions of the fort. Little remains of the fort today.

Location

[edit]The remains of Fort Cépérou are at the western edge of the present city of Cayenne, French Guiana.[2] A map from 1769 shows the fort and town in the north west of the Island of Cayenne, which lies on the Atlantic coast of Guiana between the mouths of the Cayenne and Mahury rivers, with a channel connecting the two rivers and separating the island from the coast.[3] The fort is located on Mont Cépérou, with a panoramic view over the land, the sea and the entrance to the Cayenne River. The fort was first named Fort Cépérou, then Fort Saint Michel and then Fort Saint Louis before returning to its original name.[4] The town of Cayenne grew around the protective walls of the fort.[5]

History

[edit]Background (1604–34)

[edit]In 1604 Captain Daniel de La Touche, seigneur de la Ravardière, was the first Frenchman to make a serious reconnaissance of what would become French Guiana, originally called Equinoctial France (France équinoxiale).[4] The Spanish and Portuguese had not settled this section of the coast, although it was thought to lead to the land of El Dorado.[2] Between 1616 and 1626 Dutch colonies were founded on the estuaries of the Essequibo, Berbice and Demerara rivers. In 1630 the English settled at the mouth of the Suriname River. In 1626 Cardinal Richelieu authorized colonization of Guiana. In 1630 Constant d'Aubigné ordered a colony to be installed on the shores of the Sinnamary. Captain Bontemps was tasked with colonizing the new territories with 1,200 French people.[4]

First settlement (1634–45)

[edit]An official government memoir written after 1765 says that "establishments were made at Cayenne itself in 1634 and 1636 where a fort was built near the western extremity of the island, at the mouth where the river formed the port, and above the fort, a town which has remained the capital of the colony."[6] Another source says that in 1638 merchants from Rouen built the first fort on the northwestern shore of the island of Cayenne.[2]

In 1643 Charles Poncet de Brétigny of the Compagnie du Cap du Nord, or Compagnie de Rouen(fr), arrived with 400 settlers. He bought the hill at the mouth of the Cayenne River from the local Kalina people (Caribs) and named it "Morne Cépérou" after the Kalina chief who sold it. The first wooden Fort Cépérou was built on the hill, and a village was built below it. Bretigny was ruthless and despotic, and terrorized both the colonists and the indigenous people.[6] He persecuted and enslaved the Kalinas, who responded by revolting and slaughtering many of the colonists.[4] In 1644 a Carib killed Bretigny with an axe to the head. Twenty-five Frenchmen survived, but none left Guiana alive.[6]

Fresh settlement attempts (1652–76)

[edit]

In September 1652 the twelve seigneurs of the Compagnie de la France équinoxiale landed 800 men at the tip of the Pointe du Mahury, where they found the 25 survivors of the Compagnie de Rouen. Jean de Laon, a king' engineer, replaced the wooden walls of the fort with a stone bastion called Fort Saint Michel. The purpose was to guard against attacks from the Caribs across the river, and attacks by the English and Dutch.[4] All of the settlers had soon been killed by the Caribs or had escaped to Barbados.[6] Guerin Spranger obtained a grant from the States General of the Netherlands and established a Dutch colony on Cayenne Island around 1656.[7][a] By 1660 there were no Frenchmen left in Guiana.[6]

In 1664 Jean-Baptiste Colbert sent a force of 1,200 to recapture Cayenne from the Dutch.[6] The town was rebuilt with 200 huts, and had 350 French settlers and 50 slaves.[2] In 1666 the English commanded by Captain Peter Wroth visited the colony of Cayenne but did not harm the governor Cyprien Lefebvre de Lézy.[9] Cayenne was sacked by an English fleet under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir John Harman in August 1667.[9] Harman's fleet destroyed the fort and the town of Cayenne.[10] After they left, from December 1667 the Jesuit father Jean Morellet was the de facto governor until the new governor Antoine Lefèbvre de La Barre arrived.[11]

The Dutch vice admiral Jacob Binckes arrived at Cayenne on 4 May 1676 and landed 900 troops near Fort Saint Louis (Fort Cépérou) the next day. Lefebvre soon surrendered. Binckes left shortly after for Marie-Galante and Tobago, leaving a small force to hold Cayenne.[12] On 18 December 1676 French troops under vice-admiral Jean II d'Estrées took the city back from the Dutch.[4] After this the colony was French until the time of Napoleon, but it failed to prosper. In 1685 the total population of colonists and slaves was just 1,682.[6]

Zenith and decline

[edit]

A 1677 map, still using the Dutch name of Bourg Louis, shows a watchtower, some small batteries and a miniature star-shaped fort on Morne Cépérou. A report that year says the small (peu spacieux) fort had walls that were so thin they were disintegrating.[13] In 1689 new fortifications for the town were laid out by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, the king's engineer.[4] Vauban's fortifications were built between 1689 and 1693.[14] The original Fort Cépérou remained, surrounded by the much more extensive ramparts of Vauban.[15]

In 1701 the structures in the fort were destroyed by a fire that spread to the palm-thatched huts of the city. The Portuguese occupied Guiana from 1809 to 1817 and destroyed all the defenses of Cayenne Island. The remains of the town's walls were torn down, the fort's bastions were destroyed, and only three dilapidated buildings remained of the fort. In 1862 governor Louis-Marie-François Tardy de Montravel had a lighthouse built on Mount Cépérou. By 1864 the fort was almost abandoned.[4]

A great fire destroyed the southeast part of Cayenne in August 1888. The bell on the fort's pagoda rang for eight days during the fire until it split on 12 August 1888. A public clock was installed on the site in the first half of the 20th century.[4] Some walls and a bell tower are all that remain.[5] The pagoda holding the bell is classified as a monument historique. In 2016 work was done to rehabilitate the pagoda, which was in danger of collapse. The site was transferred from the armed forces to the city of Cayenne in February 2009.[4]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Brett, William Henry (1868). The Indian Tribes of Guiana. London: Bell and Daldy. p. 46. ISBN 0332505170.

- ^ a b c d Marshall 2009, p. 226.

- ^ Tirion 1769.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Les origines du Fort Cépérou ... Mairie.

- ^ a b Fort Cépérou – WorldEventListings.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bailey 2018, p. 31.

- ^ Arbell 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Van Panhuys 1930–1931, p. 535.

- ^ a b Hulsman, Van den Bel & Cazaelles 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Chérubini 1988, p. 35.

- ^ Roux, Auger & Cazelles 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Pritchard 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Bailey 2018, p. 89.

- ^ Bailey 2018, p. 224.

- ^ Bailey 2018, p. 225.

Sources

[edit]- Arbell, Mordehay (2002), The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean: The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas, Gefen Publishing House Ltd, ISBN 978-965-229-279-7, retrieved 2018-07-27

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2018-06-06), Architecture and Urbanism in the French Atlantic Empire: State, Church, and Society, 1604-1830, MQUP, ISBN 978-0-7735-5376-7, retrieved 2018-07-26

- Chérubini, Bernard (1988), Cayenne, ville créole et polyethnique: essai d'anthropologie urbaine (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-86537-200-3, retrieved 2018-07-25

- "Fort Cépérou", Lonely Planet, retrieved 2018-07-25

- "Fort Cépérou", WorldEventListings, retrieved 2018-07-25

- Hulsman, Lodewijk; Van den Bel, Martjin; Cazaelles, Nathalie (December 2015), ""Cayenne hollandaise" Jan Claes Langedijck et Quirijn Spranger (1654-1664)", Karapa (in French), 4, Association AIMARA, retrieved 2018-07-25

- "Le fort Cépérou", Fier d’être Guyanais (in French), 11 February 2016, retrieved 2018-07-26

- Les origines du Fort Cépérou et de la ville de Cayenne (in French), Mairie de Cayenne, retrieved 2018-07-26

- Marshall, Bill (2009), The French Atlantic: Travels in Culture and History, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-1-84631-051-5, retrieved 2018-07-26

- Pritchard, James S. (2004-01-22), In Search of Empire: The French in the Americas, 1670-1730, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82742-3, retrieved 2018-07-25

- Roux, Yannick Le; Auger, Réginald; Cazelles, Nathalie (2009), Loyola: L'Habitation des Jésuites de Rémire en Guyane Française (in French), PUQ, ISBN 978-2-7605-2451-4, retrieved 2018-07-25

- Tirion, Isaak (1769), Land-kaart van het eiland en de volksplanting van Cayenne (in Dutch), retrieved 2018-07-26

- Van Panhuys, L. C. (1930–1931), "Quijrijn Spranger", De West-Indische Gids (in Dutch), 12, Brill on behalf of the KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies: 535–540, JSTOR 41847925