Bend (heraldry)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| Part of a series on |

| Heraldic achievement |

|---|

| External devices in addition to the central coat of arms |

|

|

In heraldry, a bend is a band or strap running from the upper dexter (the bearer's right side and the viewer's left) corner of the shield to the lower sinister (the bearer's left side, and the viewer's right). Authorities differ as to how much of the field it should cover, ranging from one-fifth (if shown between other charges) up to one-third (if charged alone). The supposed rule that a bend should occupy a maximum of one-third of the field appears to exclude the possibility of two or three bends being shown together, but contrary examples exist.[citation needed] Outside heraldry, the term "bend (or bar) sinister" is sometimes used to imply ancestral illegitimacy.

Modified bends

A bend can be modified by most of the lines of partition, such as the bend engrailed in the ancient arms of Fortescue and the bend wavy in the ancient coat of Wallop, Earls of Portsmouth.

Bend sinister and "bar sinister"

The usual bend is occasionally called a bend dexter when it needs to contrast with the bend sinister, which runs in the other direction, like a sash worn diagonally from the left shoulder (Latin sinister means left). The bend sinister and its diminutives such as the baton sinister are rare as an independent motif; they occur more often as marks of distinction. The term "bar sinister", is an erroneous term when used in this context, since the "bar" in heraldry refers to a horizontal line.

The bend sinister, reduced in size to that of a bendlet or baton, was one of the commonest brisures (differences) added to the arms of illegitimate offspring of European aristocratic lords.[1][2] A narrow bendlet or baton sinister was the usual mark used to identify illegitimate descendants of the English royal family dating from fifteenth century. For example, Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d.1542), illegitimate son of Edward IV of England, bore the arms of the House of York with a bendlet sinister overall.[2][3][4] The full-sized bend sinister was seldom used in this way, and more recent examples also exist of bends sinister that have no connection with illegitimacy, such as in the arms of the Burne-Jones baronets.[5][6]

Royal descent was considered a mark of honour, even if it was illegitimate as denoted by the addition of the bend sinister.[4] In most of Europe, illegitimate children of nobles, despite having few legal rights, were customarily regarded as noble, and married within the most aristocratic families.[2] Marks of illegitimacy were never subject to strict rules,[7][8] and the customary English use of the bend, bendlet, and baton sinister to denote illegitimacy in this way eventually gave way to the use of different kinds of bordures.[3]

Sir Walter Scott is credited with inventing the phrase bar sinister, which has become a metonymic term for bastardy.[9][10] Heraldry scholar Arthur Charles Fox-Davies and others state that the phrase derives from a misspelling of barre, the French term for bend.[1][7][6] Despite its not being a real heraldic symbol (a bar cannot actually be either dexter or sinister since it is horizontal), bar sinister has become a standard euphemism for illegitimate birth.[9][11]

Diminutive forms

The diminutives of the bend, being narrower versions, are as follows, in descending order of width:

- Bendlet: One-half as wide as a bend, as in the arms of Manchester City Council, England. A bendlet couped is also known as a baton,[12] as in the coat of Elliot of Stobs[13]

- Cotise: One-fourth the width of a bend; it appears only in pairs, one on either side (French: coté) of a bend, in which case the bend is said to be cotised as in the ancient arms of Fortescue and Bohun and in the more modern arms of Hyndburn Borough Council, England.

- Riband or ribbon: Also one-fourth the width of a bend. It is also called a cost as in the arms of Abernethie of Auchincloch (Or, a lion rampant gules surmounted of a cost sable, all within a bordure engrailed azure — first and fourth quarters)[14]

- Scarp (or Scarf): the diminutive of the bend sinister.

Other

In bend

The phrase in bend refers to the appearance of several items on the shield being lined up in the direction of a bend, as in the arms of the ancient Northcote family of Devon: Argent, three crosses-crosslet in bend sable.[15] It is also used when something is slanted in the direction of a bend, as in the coat of Surrey County Council in England.[16]

Bendwise

A charge bendwise is slanted like a bend. When a charge is placed on a bend, by default it is shown bendwise.

Party per bend

A shield party per bend (or simply per bend) is divided into two parts by a single line which runs in the direction of a bend. Applies not only to the fields of shields but also to charges.

Bendy

Bendy is a variation of the field consisting (usually) of an even number of parts,[17] most often six; as in the coat of the duchy of Burgundy.

Analogous terms are derived from the bend sinister: per bend sinister, bendwise sinister, bendy sinister.

Gallery

-

Party per bend, argent and gules

-

Argent a bend sinister gules

-

Argent a bendlet gules

-

Argent a ribband gules

-

Argent a baton gules

-

Bendy of six, gules and argent

-

Argent a bend cotised gules

-

Arms of the Fortescue family: Azure, a bend engrailed argent plain cotised or

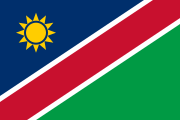

In national flags

-

Flag of the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Azure, a bend sinister gules fimbriated or, in dexter chief a star of the last.

-

Flag of the Republic of the Congo: Per bend sinister vert and gules, a bend sinister or.

-

Flag of Papua New Guinea: Per bend gules and sable, in chief a bird of paradise or, and in base the stars of the Southern Cross argent.

-

Flag of the Solomon Islands: Per bend sinister azure and vert, a riband sinister or, in dexter chief five stars in saltire argent.

-

Flag of Saint Kitts and Nevis: Per bend sinister vert and gules, on a bend sable fimbriated or two stars argent.

-

Flag of Trinidad and Tobago: Gules, a bend sable fimbriated argent.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Woodward, John (1896). A Treatise on Heraldry, British and Foreign: With English and French Glossaries: Volume 2. Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 172.

- ^ a b c Montagu, J. A. (1840). A Guide to the study of Heraldry. London: William Pickering. pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Boutell (1914), pp. 190–1.

- ^ a b Bertelli, Sergio; Litchfield, R. Burr (2003). The King's Body: Sacred Rituals of Power in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Penn State Press. pp. 174–5. ISBN 0271041390.

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 512.

- ^ a b O'Shea, Michael J. (1986). James Joyce and Heraldry. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780887062704.

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), p. 508.

- ^ Woodward, John; Burnett, George (1892). A Treatise on Heraldry, British and Foreign: With English and French Glossaries: Volume 2. Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 553. ISBN 0-7153-4464-1. LCCN 02020303.

- ^ a b Wilson, Kenneth (2005). The Columbia Guide to Standard American English. Columbia University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780585041483.

- ^ Freeman, Jan (2009). Ambrose Bierce's Write It Right: The Celebrated Cynic's Language Peeves Deciphered, Appraised, and Annotated for 21st-Century Readers. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 29. ISBN 9780802719706.

- ^ Hogarth, Frederick; Pine, Leslie Gilbert. "Heraldry: The scope of heraldry". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Boutell (1914), p. 58.

- ^ Public Register volume 1, page 144.

- ^ Public Register volume 1, page 69

- ^ a b Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.604

- ^ "Civic Heraldry of England and Wales – Weald and Downs Area". www.civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Boutell (1914), p. 59.

References

- Boutell, Charles (1914). Fox-Davies, A.C. (ed.). The Handbook to English Heraldry (11th ed.). London: Reeves & Turner (via Project Gutenberg). OCLC 81124564.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry: Illustrated by Nine Plates and Nearly 800 Other Designs. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack. ISBN 0-517-26643-1. LCCN 09023803.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Boutell, Charles (1890). Heraldry, Ancient and Modern: Including Boutell's Heraldry. London: Frederick Warne. OCLC 6102523

- Brooke-Little, J P, Norroy and Ulster King of Arms, An heraldic alphabet (new and revisded edition), Robson Books, London, 1985 (first edition 1975); sadly very few illustrations

- Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, fully searchable with illustrations, http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk

- Clark, Hugh (1892). An Introduction to Heraldry, 18th ed. (Revised by J. R. Planché). London: George Bell & Sons. First published 1775. ISBN 1-4325-3999-X. LCCN 26-5078

- Cussans, John E. (2003). Handbook of Heraldry. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7338-0. LCCN 04-24470

- Friar, Stephen (ed) A New Dictionary of Heraldry Alphabooks, Sherborne, 1987

- Greaves, Kevin, A Canadian Heraldic Primer, Heraldry Society of Canada, Ottawa, 2000, lots but not enough illustrations

- Heraldry Society (England), members' arms, with illustrations of bearings, only accessible by armiger's name (though a Google site search would provide full searchability), https://web.archive.org/web/20091116220334/http://www.theheraldrysociety.com/resources/members.htm

- Heraldry Society of Scotland, members' arms, fully searchable with illustrations of bearings, http://heraldry-scotland.com/copgal/thumbnails.php?album=7

- Innes of Learney, Sir Thomas, Lord Lyon King of Arms Scots Heraldry (second edition)Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1956

- Moncreiffe of Easter Moncreiffe, Iain, Kintyre Pursuivant of Arms, and Pottinger, Don, Herald Painter Extraordinary to the Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms Simple Heraldry, Thomas Nelson and Sons, London and Edinburgh, 1953.

- Neubecker, Ottfried (1976). Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-046312-3.

- Royal Heraldry Society of Canada, Members' Roll of Arms, with illustrations of bearings, only accessible by armiger's name (though a Google site search would provide full searchability), http://www.heraldry.ca/main.php?pg=l1

- South African Bureau of Heraldry, data on registered heraldic representations (part of National Archives of South Africa); searchable online (but sadly no illustration), http://www.national.archsrch.gov.za/sm300cv/smws/sm300dl

- Volborth, Carl-Alexander von (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole, England: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-0940-5. LCCN 81-670212

- Woodcock, Thomas and John Martin Robinson (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0-19-211658-4. LCCN 88-23554

External links

Media related to Bends in heraldry at Wikimedia Commons

- Canadian Heraldic Authority, Public Register, with many official versions of modern coats of arms, searchable online

- International Heraldry & Heralds, heraldry information by James McDonald