|

D-Lib Magazine

March/April 2014

Volume 20, Number 3/4

Table of Contents

Participatory Cultural Heritage: A Tale of Two Institutions' Use of Social Media

Chern Li Liew

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

chernli.liew@vuw.ac.nz

doi:10.1045/march2014-liew

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine how and to what extent cultural heritage institutions (CHIs) are currently using social media to create a culture of participation around their digital collections and services. An environmental scan of New Zealand CHIs with a social media initiative was conducted and four cases with considerable activities, participatory communication and user-generated contents were investigated. Two of these case studies are reported in this paper. The two sites were chosen, firstly, on the basis of their having levels of participatory activity significant enough to merit in-depth analyses; and, second, on their ability to provide contrasting examples of different approaches and practices. The purpose of the comparison is to highlight the different nature and extent of participatory culture and user generated/contributed contents. While one of the sites belongs to a major national institution, the other represents a regional, community-level initiative. Further, while one site employs a self-hosted Web 2.0 platform, the other utilises a third-party platform. Finally, while one is aimed primarily at displaying and promoting images from an archival collection while enabling user commenting, the other actively seeks contributions to share and co-construct local history stories.

1.0 Introduction

The ability of an individual or a community to comment on, create, upload and share digital cultural content demonstrates a growing demand for creative expression, the exploration of identity and for cultural participation. A growing number of CHIs including archives, libraries and museums have responded to the challenge of providing authentic and authoritative information within an increasingly participatory online environment. Many CHIs now manage sites where cultural heritage contents are examined and where users and communities of interests collaborate in the 'making of meaning' and co-construction of memories (Terras, 2011; Freeman, 2010; Falk, 2006; Gurian, 2006), rather than places where cultural authority is asserted. These projects represent a shift in how CHIs act as trusted cultural heritage guardian and facilitating access to cultural contents.

According to Russo, et al. (2008), "the challenges that social media bring demonstrate an enhancement of the traditional one-to-many information transfer model with a more genuinely interactive many-to-many communication model, in which institutions use their own voice and authority to encourage participatory communication with individuals and communities of interest or practice." (p.28). By using social media as part of their curatorial practice or communication with users and stakeholders, CHIs can open up their previously 'guarded' collections and communications, to privilege engagement and participation by users and communities of interest. Sharing cultural heritage contents through Web 2.0 spaces expands opportunities for institutions and their communities of interest to actively use and reuse these contents. It also provides opportunities for counteracting the silo effect of limiting access to these contents to institutional websites and repositories (Zorich, Waibel and Erway, 2008) and for building cross-institutional collections (Palmer, Zavalina and Fenlon, 2010).

Within a few years, a number of pioneering CHI Web 2.0 projects were underway, accompanied by a growing body of professional and academic literature that both documented and advocated on behalf of such initiatives (van den Akker, et al., 2011; Cocciolo, 2010; Nogueira, 2010; Daines and Nimer, 2009; Samouelian, 2009; Huvila, 2008; Krause and Yakel, 2007; Chad and Miller, 2005). Web 2.0 implementation has become sufficiently well-established; enough to require attentive consideration from all who work within the cultural heritage field. However, despite its current high profile, it is important to remember that social media use by CHIs is still only within its first decade. Most effort consequently remains highly exploratory in character. The outlines of the prevailing forms it will acquire and the overall impact it will have on the profession are yet to settle into definitive patterns (Theimer, 2011). Theimer alludes to the fluid and experimental nature of current activity within this field and to the necessity of CHIs undergoing a learning process in order to find out how their institution might best adjust to the new opportunities and challenges represented by Web 2.0. Palmer and Stevenson (2011, p.2) describe the present moment as "a period of flux" in which CHI professionals are faced with "discovering new ways of engag[ing] with end-users and [working within] new spaces"; of "negotiating issues of control, authority, voice, and trust"; of "defining and targeting an audience, establishing clear objectives, measuring successes, and delineating the personal from the professional".

2.0 Social media and Participatory Culture

If there is one word that highlights the particular quality of social media, it would probably be 'participation'. Unlike the mass media before it, social media is fundamentally designed as a participative medium. Cultural theorist Jenkins (2006) observes that with the emergence of Web 2.0, a paradigm shift has occurred in the way media content is produced where audiences are empowered to participate in the culture. One of the consequences of the shifts in media paradigms from the 20th Century 'packaged' media to the 21st Century 'conversational' media is that notions of authorship, creativity and collaboration have become part of everyday culture rather than remaining in the hands of the authoritative institutions. This changes the culture into a participatory one where ordinary citizens express themselves and share their opinion with others. For some critics like Jenkins (2006), social media is part of the rise of participatory culture which empowers users to generate and produce content, moving from the mode of action characteristics of 'audiencing' to the mode characteristics of producing. Bruns (2009) believe users move between these modes and he calls these users the 'produsers', i.e. users playing an active role in producing contents rather than just interpreting them. The main picture drawn is that Web 2.0 has become a medium for sharing and for conversations, rather than for dissemination and control.

Of all the opportunities made possible by social media, perhaps the most advantageous to CHIs is indeed, the ability to foster participant engagement between an institution and its users and communities of interests. Some have likened the potential transformation to "a transition from Acropolis — that inaccessible treasury on the fortified hill — to Agora, a marketplace of ideas offering space for conversation, a forum for civic engagement and debate, and opportunity for a variety of encounters" (Proctor, 2010).

It is noteworthy that for some, social media is part of broader structural affordances of a capitalist economy (Andrejevic, 2011) in which users' free labour is exploited for the benefit of the corporations (Andrejevic , 2011; Lovinck, 2012). However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to engage in a philosophical discussion about social media and the complex social processes it engages with. The concept of participatory culture is being used here as a way of distinguishing the focus of the case studies from the more traditional modes of participation that took place 'behind closed doors' (e.g. prototyping new projects with focus groups and consultation with relevant community groups when designing an exhibit).

2.1 Rationale for participatory culture in CHIs

Preserving a community's cultural heritage has been among the responsibilities of CHIs. With the emergence of various Web 2.0 applications, many are now facing a demand in the era of participatory culture where members of the community are expected to get involved. They expect to be able to participate through for instance, sharing and contributing documents and contextual information (e.g. photos, personal diary entries) that have the potential to enrich and add value to the histories, or participate in co-curating of memories collection. A number of CHIs in New Zealand have responded to this demand and it is the aim of this paper to present two of the case studies conducted to highlight current practices.

Enthusiastic digitisation and 'curating' of information by amateurs can be a potential rich source of cultural heritage content that documents areas not covered by traditional CHIs. These amateur collections might form useful complements to institutional collections. Linking a stand-alone CHI website into websites such as Flickr, which have an in-built audience and a platform that encourages general public to contribute relevant materials to institutional digital collections may provide a way to increase the use of digitised heritage content. Terras (2011) discuss examples of how Flickr is used as a platform for generating amateur cultural heritage content. By acknowledging and integrating such user-contributed contents to their own collections, CHIs may be able to invigorate not only their online presence and extend the use of collections, but also to enrich their heritage collections.

Three non-exclusive categories of motivation have been generally identified. The first relates to the perception that implementing some form of Web 2.0 was a practical "business" necessity, given users' and stakeholders' expectations within the present operating environment (Daines and Nimer, 2009; Chad and Miller, 2005). The second involves the belief that participatory platforms will help further the pursuit of core cultural heritage goals by creating wider educational opportunities and strengthening the information base through leveraging users' knowledge (Oomen and Aroyo, 2011; Proctor, 2010). The third category of aims has the potential to be transformational and relate to the idea that participatory platforms will enable CHIs to move beyond the seemingly 'elitist' aspects of their traditional practice (Flinn, 2010).

3.0 Research Design

By drawing on analyses of activities that are documented in the CHIs social media platforms (including the user-generated, contributed contents), this study investigates the extent of participatory culture in CHIs. The chosen approach takes its cue from an observation by Yakel (2011) who argues that in order to gain a better understanding of "the dynamics of peer production" that is actually occurring on these sites, there is a need for "[m]ore research showing the nature of use, the volume of the comments, and the resulting conversational threads" (p.97). This might be contrasted with the prevailing character of current research in this field which tends to consist of either general surveys (Samoelien, 2009) or practitioners' reports focused on the process of implementation (Cocciolo, 2010). While such studies may provide examples of user-generated contents and some indication of the amount of such contents, they usually do not subject that content to systematic analysis.

As Yakel (2011) indicates, undertaking an in-depth analysis of activities and contents generated via social media can help provide insights into the specific character and extent of user participation and interaction that is actually occurring on that site. That in turn may help point to the sort of steps that still need to be taken in order to better encourage the emergence of the kind of sustainable online community engaged around heritage content that has often been posited as an objective for initiatives of this kind.

One of the main points of focus in the content analyses undertaken in this study therefore, is on the extent to which each CHI social media initiative might be seen to be making progress towards this goal of developing a sustainable community of users engaged in active participation and interaction with each other around the cultural content.

3.1 Selection of case studies

An environmental scan of Web 2.0 implementation by New Zealand CHIs was undertaken with the focus on social media applications that are specifically used in conjunction with the presentation and co-creation of heritage content. This is to distinguish from the general, popular use of Web 2.0 by CHIs such as institutional blogs, Facebook pages, Twitter feeds which are largely about presenting news and events, discussions of professional activity and for promotional purposes. In other words, they are generally not used for the presentation and discussion of heritage content. These kinds of Web 2.0 applications have therefore been excluded from the content analysis.

The criteria used to select the case studies institutions included a variety of factors, most notably that the institutions have (i) a significant number of heritage items that are Web 2.0-enabled and (ii) a significant amount of user activity (i.e. evidence that a significant number of different users had posted comments on a significant number of different items). The Appendix lists the CHIs examined in the preliminary stage of the study.

In the second stage, four in-depth case studies were conducted: NLNZ on The Commons (NLNZ Commons), The Prow, NZ History Online and Kete Horowhenua (KH). The cases were selected firstly on the basis that they showed sufficient evidence of user participation via Web 2.0 applications to merit further investigation.

In this paper, two of these case studies representing two different types of initiatives are discussed. The two sites were chosen, firstly, on the basis of their having levels of participatory activity significant enough to merit investigation; and, second, on their ability to provide contrasting examples of different approaches and practices. The purpose of the comparison is to highlight the different approaches taken and the nature and extent of participatory culture and user generated/contributed contents. While one of the sites (NLNZ Commons) belongs to a major national institution, the other (KH) represents a regional, community-level initiative. Further, while one site employs a self-hosted Web 2.0 platform (KH), the other utilises a third party platform (NLNZ Commons). Finally, while one is aimed primarily at displaying and promoting images from an archival collection while enabling user commenting (NLNZ Commons), the other actively seeks contributions to share and co-construct local history stories (KH).

3.2 Content analysis process

The following types of user-generated and contributed content were considered: (i) situations where users were able to upload and share their own heritage-related images, stories, etc. to a site and (ii) where users were able to post comments about a heritage-related item on the site.

The contents were subject to a detailed analysis which included coding posts in terms of various categories (e.g. those that asked a question, those that offered an appreciation, those that added (contextual) information, those that added a personal reminiscence, those relating to family history enquiries, those related to school projects, etc.). Site administrators' comments were also analysed and coded in a similar fashion (e.g. those responding to a question, those providing a response to an appreciation or reminiscence, etc.). Patterns of inter-relationships between posts were also analysed in order to identify any signs of on-going interaction or sustained discussion between users, or between users and administrators, that might be interpreted as evidence of participatory communication.

Where available, supporting documentations such as policy statements and published writings were also examined to gain insights into the CHIs thinking behind the rationale, the underlying motivations and the practice for their social media practices.

4.0 Case Studies

4.1 NLNZ on The Commons

Background and character of site

The National Library of New Zealand (NLNZ), which incorporates the Alexander Turnbull Library heritage collections, is one of New Zealand's most pre-eminent CHIs. While the nation's other two main state heritage institutions, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Archives New Zealand have made some use of social media, these have been largely confined to formats like blogs, Facebook pages and Twitter feeds. The focus is mainly around events promotion and professional activities, rather than providing access to their cultural heritage collections. NLNZ is as yet, the only national CHI to undertake the display of a significant amount of its heritage material within a Web 2.0 format that permits users to directly annotate and comment on collection items. Notably, it has chosen to do so via the use of a third-party platform — in this case the photo sharing website Flickr. This is a significant point of difference between it and the other case study (KH) examined in this paper. It is also in contrast with its trans-Tasman counterpart, the National Library of Australia's Trove which supports a number of Web 2.0 features on its own platform.

The platform NLNZ specifically makes use of is The Commons, a subsection of Flickr intended to deal with the particular needs of pictures sourced from heritage repositories. Launched in 2008 as a pilot project with the Library of Congress, The Commons is based around the idea of using a special "no known copyright restrictions" license to facilitate the release of CHI collection material online. The site's own homepage describes The Commons project as having two principle objectives. The first is to show users the "hidden treasures in the world's public photography archives"; the second, to demonstrate how their "input and knowledge can help make these collections even richer." (The Commons on Flickr) While the former goal is primarily about providing better access to these images, the latter situates The Commons within an interactive crowdsourcing model. A Flickr blog post celebrating the 4th anniversary of the launch of The Commons also highlights its participatory culture potential by noting how "[t]here have been instances where Flickr members contributed context and story-telling around a photo which was then verified by the institutions and even added to the official records of that photo." (Miller, 2012)

Published reports from CHI participants in The Commons have been generally enthusiastic, especially with regard to the benefits of being able to access the enormous traffic generated by "the global reach of Flickr and its active international user base" (Chan, 2008). Many individual examples have also been cited of users productively engaging with CHI content via The Commons (Bernstein, 2008). There is as yet however, little independent research on the overall extent, character and quality of the participatory activity on the site. One preliminary study suggests that this may be currently quite small in relation to the site's overall numbers. Out of a sample of 106,352 images, Henman (2011) found that only 3,218 photos (3%) had comments attached, only 236 (0.22%) had notes, and only 17% of tags had been added by users not affiliated with the contributing CHI. A more widely expressed concern is the risks involved in CHIs entrusting their social media presence to commercial vendors driven by business motives — who, consequently, might not be around long-term (Tennant, 2010).

Flickr's own statistics indicate that (as of December 2013), The Commons had over 200,000 images contributed by 56 participating CHIs, with more than 130,000 comments added by users.

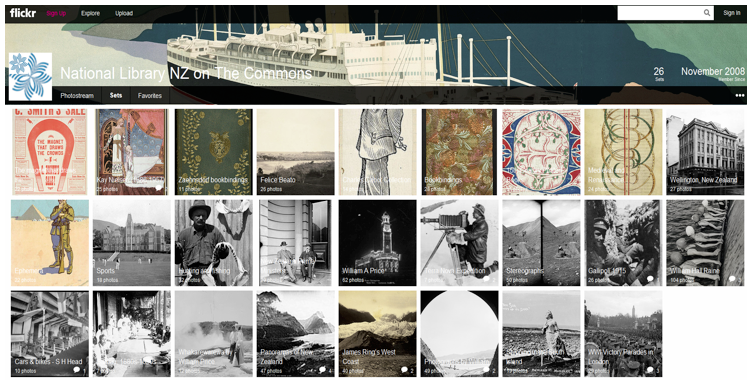

Figure 1: The National Library of New Zealand on The Commons

NLNZ became a partner in The Commons in November 2008; although it had been trialling the use of Flickr photostream for about a year prior to that (Johnston, 2008). As of December 2013, NLNZ on The Commons contained 26 sets of photos (Figure 1). A "set" is a themed grouping of images with either the same creator, subject matter, location or medium in common. Of the NLNZ sets on The Commons at the time this research was conducted, three were related to printed ephemera, four to books, with the remaining nineteen photograph collections. Most of these sets contained between 20 and 50 pictures, with the smallest set containing 7 photos and the largest, 104 images. No figure was provided for the overall number of images in NLNZ's Flickr photostream. However, a tally of numbers for individual sets (which does not preclude duplicates) gave an estimated total of around 800.

Some useful insights into the motivations and expectations behind NLNZ's decision to join The Commons are provided in a 2008 NLNZ blog post written by its then Web manager (Johnston, 2008). This identifies the two-fold purpose behind its year-long trialling of a Flickr photostream as being, first, to "[a]ttract users who do not know about our collections, or haven't thought about visiting our subsites"; and, second, to "[o]bserve the tagging and commenting behaviours" of users. The latter objective was to see what issues or benefits might arise for NLNZ from enabling these forms of participation. Johnston observed that while visitation numbers had been pleasingly high for this pilot photostream, there had been much less user input than hoped for. She also noted that most of the comments posted had been "of the 'great photo' variety", with a small number providing more information about an image, and an even smaller number asking questions. Statistics also showed that in terms of attracting traffic from Flickr back to NLNZ's own websites, there had been a click-through ratio of one click per collection image. However, as Johnston rightly noted, the lack as yet of any established benchmarks for appraising CHI social media use makes it difficult to judge whether the above figures represent a reasonable degree of success or not. Overall, Johnston (2008) considered Flickr "a good way of dipping a toe in the social media water", especially in terms of the relatively low amount of "time and energy" NLNZ was required to invest in it.

Recent events appear to confirm the largely exploratory approach NLNZ has taken to its participation in Flickr so far. Sometime around May 2012, NLNZ reduced the number of sets on its Flickr photostream from 26 to 10, and the corresponding number of images from around 800 to around 200. In response to an enquiry as to why this was done1, NLNZ explained that it was as a result of the organization's decision to not, at that moment to renew its Flickr Pro account. Without this, Flickr members are restricted to having no more than 200 images on view at a time. NLNZ stressed however, that this was only a temporary state of affairs and did not entail the loss of any user-generated content previously posted on the site. The reason behind NLNZ's decision to let its Flickr Pro subscription temporarily lapse was given as the organization's wish for time out in order to develop a better "sense of how we wanted to use the site, and how we could make it an active part of our interaction with the public." It was felt that NLNZ on The Commons suffered from a "lack of a clear direction, and sense of how [it] would be supported (both with fresh items and dedicated community engagement)". What was required therefore was "time to build a proper social media/web service plan". It was also noted that this situation had been compounded by NLNZ having at that time, had its hands full with both a major refurbishment of its premises and the launch of a new website. This severely limited the time and energy it had been able to provide for its Flickr sets. It was NLNZ's belief that it would be better able to achieve its "overarching goal" of "connect[ing] New Zealanders with the collections (and services) that matter to them" if it took time to identify how its presence on The Commons could play "a defined role, with fresh and regular uploads, genuine engagement with other users, and dedicated support inside the Library."1 It appears (as of December 2013) that NLNZ has resumed the 26 sets of photos.

Provision for user-generated/contributed content

Adding comments about an image that others can respond to is one of the principle ways users can participate within NLNZ on The Commons. They can also select an image as a favourite, which bookmarks it on their own photostream enabling any visitors there to also view it. Users can 'tag' a picture by adding a keyword of some kind to improve its findability. They can add 'notes' that appear directly on a particular section of an image whenever it is hovered over. While users cannot directly contribute their own images to the NLNZ sets, they can add pictures via the comments application. This opens up the possibility of users posting photographs that relate in some way to the image uploaded by NLNZ, or that provide examples of a mash-up or re-use of that picture. Another form of re-use available to users is to set up a separate themed "Group" photostream. This enables users to re-present images found elsewhere on Flickr in terms of a particular interest. In order to do this, the administrator of a group needs to post a comment on a picture requesting NLNZ's permission to re-post it within their group.

Overview of user-generated/contributed content

An analysis of comments for all 26 sets showed that most were no more than a sentence in length and had been posted within two months of the item being uploaded. Examination of the content of these comments themselves revealed that the majority were simply very short appreciations of the image on display. Typical examples were: "Excellent", "Stunning", "Awesome!!!", "WOW!", "Nice!", "Perfect shot!" A number of cases were also noted where the same user had posted the same phrase — e.g. "Great shot!" on several different photos in several different sets, seemingly deploying it as a kind of standard signature of appreciation. Brief comments or notes of a jocular nature were also common (e.g. in relation to a set of Antarctic exploration photographs: "Brrrrr!", "I love those mittens!"). These types of posts might all be categorised as what Chan (2008) refers to as "social commenting". Chan describes this as "the 'social glue' that binds the communities that play the 'Flickr game' together." According to Chan, social commenting is "really about leaving a linkback-ed mark of a visit", a networked way of saying "I was here". By posting these comments, users not only express their personal enthusiasm for an image, they also draw attention and provide other users with a link to their own photostreams. In some cases, the self-promotional aspect of these kinds of posts is quite overt, with users including large (and otherwise irrelevant) images within an item's comments thread that advertises their own photostream.

Many of the appreciations posted appeared to come from photography enthusiasts and were directed at the technical and aesthetic quality of the image ("Wonderful portrait with so great light and sharpness!", "This is stunning. Classical, reserved and intense."). A few of these even seemed to address NLNZ as if it were itself the photographer ("Congratulations! This is a wonderful shot!"). Others however, showed an awareness of the special character of this photostream as a means of providing access to items held within a CHI collection. Several of these users praised NLNZ for making its heritage images available in this way: "I really like what the National Library has done with Flickr keep more Pics coming, good work"; "Great photos! Thank you National library NZ for your progressive attitude on sharing photos with the world." Also evident was the strongly international character of the comments with many users identifying themselves as not being from New Zealand. A number of posts were also in non-English languages (a few were in Chinese or Arabic). Another very prevalent form of posts was formal requests to include one of NLNZ's images elsewhere on Flickr as part of a themed "Group". These requests came in a very standardized form — "Hi, I'm an admin for a group called [xxx], and we'd love to have this added to our group!" and appeared to be routinely added to the comments threads for all potential items of interest to that group.

While a minority overall, there were also a significant number of comments that provided additional information about an item. In some cases these offered further context for a picture by describing some personal connection to it. A set on the 1915 Gallipoli campaign for instance, received comments from users briefly recounting an ancestors' service there, or their own recent visit to that area. A few users also posted photographs in the comments thread for a picture that showed something in that historical image as it appeared today (e.g. a hill in Gallipoli, a pond in New Zealand, an Antarctic expedition ship). One example of creative re-use of an image was found where a user had posted their own colourized version of a black-and-white portrait of an Antarctic explorer that NLNZ had uploaded.

A few contributions drew on a user's own expertise in a particular area to add information not otherwise given with an image. One user for instance, provided valuable background about the German colonial circumstances in which a group of Samoan photographs had been taken. Without this, much of the significance of these images was lost. He also responded to another user's question posted on this thread several months later — indicating that he had maintained an ongoing interest in comments users made about these pictures. Another contributor usefully cut and pasted excerpts from various online sources as a way of adding more information to items. Interestingly, this included adding information about images taken from NLNZ's own websites which they themselves had not supplied for Flickr. A good example of several users contributing information about a topic and interacting with one another around it was found with a set of photos depicting merchant and naval ships. A sign of the potential benefits to be had from tapping into the knowledge of a specialist interest community, these threads showed users adding details absent from NLNZ's own metadata about the possible identity, location, or itinerary of the vessels shown. In some cases, this entailed responding or adding to suggestions offered by others (a relatively rare instance of exchanges between users found on this site). These examples offer evidence of the potential for a form of cultural heritage-related participatory culture to develop on NLNZ on The Commons. Such instances however, were comparatively rare and widely dispersed throughout the site.

NLNZ does maintain an institutional presence on Flickr by posting comments in response to those added by users. However, these posts are relatively rare. Most were added by NLNZ's then Web master, who personally signed her posts. Written in an informal, chatty style characteristic of social media exchanges, these responses largely consist of conveying thanks and encouragement to users for their comments: "You're welcome [xxx] - glad you're enjoying this photo"; "Aww, shucks, [xxx] - thanks!" In some cases, the opportunity has been taken to re-direct traffic back to NLNZ's home sites by letting appreciative users know they can view a larger image and access more information there. Particular care appears to have been taken to acknowledge the efforts of users who have added information of some kind — "WOW! Thanks for bringing these images together ... ". Nevertheless, only a minority of contributors have been responded to.

Similarly, while only a few users asked questions or suggested corrections to an item's metadata, many of these received no reply. Even for those that did, there was little evidence of significant curatorial input or of user contributed information being incorporated into NLNZ's own records. In one case where a user questioned the date provided for a picture, they were told that this would be referred to curatorial staff. It was only seven months later, after another user repeated the same question, that a reply was finally posted acknowledging that the date had, in fact been incorrect (although no thanks was offered to users for pointing this out). A subsequent post from another user observed that given this date, the identification of the photographer that NLNZ was still attributing this picture to must therefore also be wrong. Ten months on, that comment had not received a response.

Analysis

In many ways NLNZ's participation in The Commons can be judged a successful example of CHI's use of a Web 2.0 application. It has enabled an interesting selection of their heritage images, encompassing a variety of themes and styles to be made accessible to an international audience. It has also enabled this audience to engage with these images through providing feedback. While the number of comments posted is dwarfed by the impressively large number of views the site receives, they nevertheless represent a significant amount of user input. The feedback they provide is also overwhelmingly positive, with a considerable amount of praise being directed at NLNZ itself, both for the quality of its collection and its progressive attitude in making these items available on Flick in this way. If NLNZ's main objectives were to find a relatively low cost avenue of publicizing its pictorial collections, making this content more widely accessible, raising its profile internationally and promoting itself as cutting edge, then these goals can be considered to have been achieved.

If, however, NLNZ on The Commons is to be judged by the degree to which it helps facilitate the emergence of a sustainable heritage-related participatory culture around its collections, then its achievements have to be regarded as more limited. Some of the issues relate to NLNZ's decision to rely on a third-party social media platform. Considered in terms of the aforementioned strategies Yakel (2011) identifies as the principle ways in which CHIs maintain authority control within Web 2.0 environments, NLNZ on The Commons can be seen to be almost entirely dependent on separation techniques. To some extent, this containment takes place within the Flickr photostream itself, where user-generated and contributed contents remain confined to the comments thread. Far more significantly, it appears to be occurring through NLNZ's decision to isolate interaction with its heritage materials within a space that is located somewhere separated from the home sites where its databases reside. This risks relegating any user participation that occurs here to nothing more than an entertaining sideshow: something to be kept at some distance from the main event within the official venue, and where the roles of producer and consumer are kept distinctly separate and their relationship exclusively one-way.

NLNZ indicates its own awareness of this arrangement in the earlier cited blog post, marking the occasion of its first year on Flickr (Johnston, 2008). In response to a reader's comment voicing concern about what procedures were in place to ensure "the quality and value of 'crowdsourced' data", the Web master replied that this was not an issue because user-generated contents like comments and tags were "not being sucked back into the Library's own databases"; instead "all interactions remain on Flickr". If any information was provided of the kind NLNZ might consider incorporating into its catalogue records, this would be referred to curatorial staff to assess (although it was noted that so far "only a handful of comments" had been received that might qualify in this regard). Otherwise, given that NLNZ's official records were securely insulated from whatever users might add to its Flickr photostream, the Web master felt little need to moderate, verify or provide disclaimers for what was posted there, since freedom of discussion was "part of the point (and joy) of the site."

As this last remark indicates, Flickr does support the existence of a certain free-form mode of participatory culture about which there is much to applaud. It remains another question however, as to whether it also provides a suitable space for fostering the type of sustainable online user communities — adding value through thoughtful engagement with heritage content that serves as the focus of the present study. To some extent a CHI's decision to use a third-party platform like Flickr requires it to accept the need to work within the kind of Web culture that already prevails there. This limiting of its ability to shape the way users interact with its content is part of the trade-off a CHI makes for the lower costs and higher levels of traffic a large social media site provides. In the case of Flickr, this Web culture is dominated by the practice of 'social commenting'; the sheer volume of which partly derives from the vested interest users have in commenting as often and widely as possible if they wish to attract more visitors to their own photostreams. While not without value, comments of this type do tend to be fleeting, superficial and at times delivered in a routine, mechanical way. Their presence does not prevent users from making other kinds of contributions such as adding information about an item. It may, however impede comments and discussions of this sort from flourishing by swamping and dispersing them through lengthy threads dominated by "Awesome!" and "Great pic!" As a populist social media site, Flickr also tends to favor a certain 'house style' in which text speak, emoticons, typos, exclamations and a 'jokey' attitude predominate. Along with the inclusion of cryptic handles, eye-catching avatars and large promotional images within the comment threads, the prevailing sense is one of busy clutter and dashed-off, stand-alone remarks. This lends itself more to being quickly skimmed through for whatever catches the eye rather than engaged with, in the kind of prolonged, attentive way required to initiate and sustain discussion.

The photography-centric character of Flickr's Web culture might also be seen to create some potential for concern, in the sense that it might divert users' attention away from considering the historical dimensions of an image towards simply appreciating its aesthetic appeal. While not wrong in itself, this nevertheless does little to further the heritage education commitments inherent in a CHI's mission. Compounding this situation is the general paucity of descriptive information that NLNZ has provided for its Flickr sets. In part, this would seem to stem from NLNZ's evident wish to restrict the main space in which users connect with its collections to its own websites. As a consequence, it appears to have kept both the metadata and the image size on its Flickr site deliberately insufficient in the hope that this will serve to entice visitors back to its home sites, where they might then become regular users. The risk, however is that if this does not occur, then NLNZ is in the position of disseminating its images in a manner that strips them of adequate historical and archival context.

All the above concerns could be ameliorated if NLNZ maintained a more regular and interventionist presence on its Flickr photostream. Site administrators would then be able to use both the item's description space and its comments thread to actively encourage users to think about, ask questions about, add information about and discuss the cultural heritage-related aspects of these photos. However, apart from a few early and commendable efforts at building rapport through responding to users, the administrators of NLNZ on The Commons come across as only paying brief and sporadic attention to the comments posted here. In particular, they appear to show insufficient interest in using these contributions to crowdsource further context and metadata about their collection items despite this being an important part of The Commons' raison d'être. There is for instance, little to assure users that any information they provide here is being assessed for possible inclusion as a permanent part of NLNZ's own records. Nor are all users' direct questions and suggested corrections responded to. Responsibility for engaging with users around content appears to have been left almost entirely with the Web master when, in many cases, input from curatorial staff with specialist knowledge in the broad array of subject matter covered seems to have been required.

Of course, any arrangement of this kind would require a significant commitment of institutional resources and a more formal set of policies and guidelines. It therefore needs to be viewed within the context of the CHI's other obligations. At a time when the organization has had its hands full with two major infrastructure projects1, it is easy to understand how maintaining an effective administrative presence on Flickr might have become a low priority. As also acknowledged in that email, the degree of planning and resources NLNZ has committed so far to managing its site on The Commons has not been adequate to the task of establishing and achieving clear objectives for being there. Again, this is understandable given how, as elaborated in the Introduction, CHI use of Web 2.0 remains still mostly in an experimentation phase, with many organizations having required time to gain a better understanding of what Web 2.0 applications can do for their institutions and communities of interests, and what is needed to make them work effectively. NLNZ's partnership in The Commons has so far had an exploratory character about it. It seems a positive sign then, that it recognizes the need to dedicate more thought and resources to this exercise in user participation if it is going to take it forward. What seems less positive though, is the fact that it had felt it necessary, as part of this development process, to temporarily remove the majority of user-generated contents already posted on that site. This 'pulling back' could have potentially damaged the image of the institution and its social media practice. If, however the (now) resurrected photostreams are now better resourced and more closely managed, there is potential for NLNZ on The Commons to build on the signs of incipient user communities and crowdsourcing activity already present, to create an effective participatory culture around its heritage contents.

4.2 Kete Horowhenua

Background and character of site

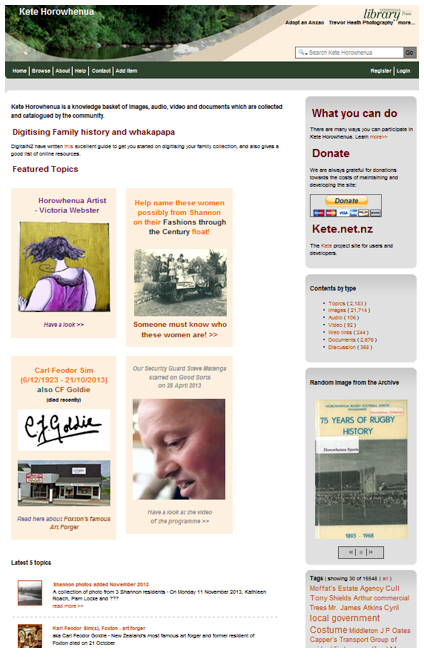

Kete Horowhenua (KH) is an example of a community-level social media initiative. Launched in 2007, it is managed by Horowhenua District Libraries and was developed with funding from the Community Partnership Fund (CPF), part of the New Zealand Government's National Digital Strategy. This funding programme was specifically aimed at supporting ICT projects that addressed the needs of local communities and incorporated their participation. With a total population of just over 30,000, the district that KH is primarily intended to serve represents a relatively small target audience. Consequently, this is also the smallest potential contributor base among the cases looked at (see the Appendix).

Figure 2: Kete Horowhenua

KH is the first and best known of the community digital archives using the Kete open source wiki application. Describing itself as "a knowledge basket of images, audio, video and documents which are collected and catalogued by the community", KH is essentially a wiki-style digital library of cultural heritage resources. As its project manager explained in a 2008 conference paper (Ransom, 2008), the idea for it came about from the Horowhenua Library Trust's wish to find a way of supporting the local heritage sector. The latter was struggling due to a lack of the resources and premises required for preserving large collections of historical records and making these readily accessible to the public. It was feared that as a result, large amounts of history about the district was at risk of being lost. Going digital was seen as a solution to the lack of space and resourcing required for preserving a physical collection in a centralized location, while going interactive opened up the possibility of crowdsourcing as an affordable way of creating and processing content. It is worth noting that achieving a high level of local community involvement in the creation and development of this site was always as central a goal and justification for KH as heritage preservation. It was likewise a condition of the CPF funding that the project received. In the words of its project manager:

"We wanted [KH] to be self-managing and monitoring as far as possible, with no layer of library expertise needed. 'By the people for the people' was our mantra. Our community would decide what content they wanted to include and would be able to upload material in any common file format and describe it with common language. It had to facilitate the building and strengthening of relationships, not just between items in Kete, but between people as well." (Ransom, 2008)

As this suggests, the character of content on this site is deliberately kept flexible and include such things as brief encyclopedia-style stories, small local history publications and magazine articles, personal memoirs, collections of photographs or documents, audio and video clips, genealogical entries and reports on events. These items are organized and arranged under associated clusters known as 'Topics'. In terms of subject matter, the need for an online repository of heritage materials was the initial driver of this project and local heritage societies provided the bulk of the original seed collection. However, KH's brief was broadened at an early stage to also encompass arts and cultural activities, having recognized that these sectors were as constrained as the local heritage sector by the lack of suitable display space. As a consequence, the site now also hosts 'virtual exhibitions' by local artists and craftspeople which often include price lists advertising items available for sale. In addition, many other local organizations (e.g. floral societies, music groups, seniors groups, model railway clubs) use KH as a sort of community forum for promoting and reporting activities. While contributions of this kind might be considered as 'cultural heritage' defined in a very broad and inclusive way, they fall outside the emphasis on historical records and accounts of the past that serve as the focus of this study. Consequently, they have for the most part been excluded from the following analysis.

Provision for user-generated/contributed content

Given KH's strong identification of itself as community-built-and-run, there is a sense that all its content might be considered user-generated. It is true that distinctions can be drawn between for instance, already existing public collections from local heritage institutions which have been put up on the site, and personal memories and items from private collections contributed by families and individuals. The former however, is not in any way presented as if it were the 'official' content and in many cases was actually uploaded to the site, as well as arranged and described through the work of community volunteers. Similarly, while many items are credited as being created by someone identifiable as a KH administrator, there is nothing to formally distinguish these entries as constituting an institutional collection or of being more authoritative than others. Some of these items involve the Horowhenua Library Trust reporting on its own activities just like any other community organization. In many others, the administrator appears to have created the item on behalf of and in association with groups or individuals within the community. In others still, the administrator plays the role of facilitator, initiating a topic page of some kind (e.g. a list of local street names and their origins) in a way that invites users to help further develop it. Overall, the emphasis remains on the idea that this digital repository is "community-built", with all content accorded equal status.

Anyone is able to upload content to this site by registering as a member; all that is required being a name and email address. Aliases are permitted but seem to be rarely used. Kete members also have the option of adding a user image to further personalize their posts. As well as contributing their own content, any registered member can also edit material contributed by others. A section on each page identifies both who originally uploaded it and by whom it was most recently edited (one can also view a history log of this process). Using a wiki format in this way serves to further democratize the character of the site, blurring the line between user- and institutional-content by allowing anyone to have a say in how almost every item is described and arranged. KH does make provision for some topics to be sequestered into "locked baskets" that can only be edited by authorised individuals from the contributing group. However, it is a sign of their commitment to a participatory ethos that they emphasize that permission for such locked baskets is rare and only granted to organizations intending to build large or unique collections (see KH Help on Locked Baskets).

As befits the wish to develop a self-managing participatory culture, KH provides a very extensive set of instructions and guidelines, including a series of online tutorials. This is by far the most user education information found on any of the cases looked at. A comprehensive Kete Handbook of training material is available that can be downloaded as PDF files. This not only provides step-by-step guides and exemplars for using the site features, but also advice on how to be different and innovative, thereby encouraging an open-ended approach to the site's development. As a constraining influence, there is a list of house rules which are designed to "help everyone enjoy participating in the Kete website". These include the requirement of being tolerant towards others whose opinions and memories differ from their own; not being offensive or defamatory; and respecting people's privacy as well as copyright laws (see KH House Rules).

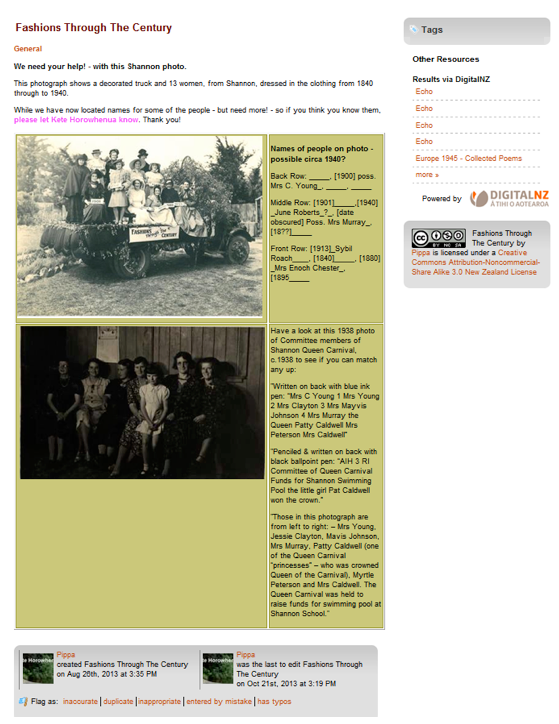

KH also enables users to add comments about an item. The contribution mechanism here appears to be specifically designed to reinforce a sense of a conversation taking place amongst individuals. There is an invitation to "Discuss this topic" and where comments have already been added, to "join this discussion." Users are also given some say in moderating other users' comments by being able to flag these as inaccurate, inappropriate, duplicates or containing typos — enabling these issues to be drawn to the attention of site administrators (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Soliciting information and commenting in Kete Horowhenua

One very important aspect of KH's user participation not necessarily apparent from the site itself but often referenced in papers and publicity materials is the degree to which this involvement has often taken place in a physical, face-to-face environment rather than a virtual one (Ransom, 2008). For instance, the initial digitization and uploading of material to the site was achieved by advertising for volunteers to come to the main library one night a week to help with this work. The response is reported to have been very enthusiastic, with large numbers of community members from a range of ages and experiences participating in 'weekly working bees' that eventually ran for nine months. As the project manager at the time noted (Ransom, 2008), because KH is Web-based, volunteers could have performed many of these tasks from home. However, the "social element" of working together with others within shared physical space appears to have proven attractive to many. The experience of working side-by-side in a collaborative manner was also found to be productive in terms of strengthening connections between library staff and the community.

Overview of user-generated/contributed content

There are a few 'virtual exhibitions' by artists to which people have added comments and it is noticeable that in these cases, they are all of the 'fan mail' type (e.g. "Great work!"). By contrast, the cultural heritage topics with comments attached are overwhelmingly of the family history/ genealogy kind, where users ask for and share information about someone; often a relative. A sizeable number of these are substantial discussion threads (i.e. three or more inter-related posts). Sometimes commenters simply note a personal connection; usually though, there is some sharing of or request for information with several of the threads having the character of a collective investigation. Such cases serve as good examples of the way collaborative Web 2.0 activity can be used to create or enhance a resource by uncovering and interlinking information that would otherwise be lost or kept dispersed. While relatively few in number on the site, these 'productive' discussion threads can nevertheless be regarded as significant additions for a small community heritage resource of this kind.

Many of these same threads also give evidence of a sense of a networked community forming around an online collection. There are several examples of friendly personal exchanges between people, with the identification of family connections and shared discussion concerning a common ancestor. Email addresses or other contact information is likewise often provided (with several of the commenters identifying themselves as living outside New Zealand). However, this kind of participatory culture activity does seem to be largely limited to people's interest in their own family histories. It does not appear to extend all that much to interactivity around the Kete resource itself, or Horowhenua heritage as a whole (i.e. those commenting largely restrict their contributions to the one particular topic). Ransom (2008) though, provides anecdotal evidence attesting to a significant offline participatory culture forming around KH through the activities of numerous local volunteers meeting up at venues like the library to source and upload content.

Running tallies of statistics available on the site (on 3 December 2013) indicate that there are currently 2183 Topics on Kete; with 27714 images, 106 audio files, 92 video files, 244 weblinks, 2676 documents, and 368 contributions to the discussion thread. These figures appear to indicate a very healthy amount of content being added for a Web 2.0 repository serving a local community of this size. However, as already noted, it is difficult to differentiate what counts as user-generated from institutional content. For instance, many of the items credited as being created by "Kete Administration" appear to be in fact, community contributions that have either been merely uploaded by staff or else by community volunteers using that logon while working at the library. Of the material most clearly identifiable as user-generated, a large proportion is not directly heritage-related but rather exhibitions by craftspeople or activity reports from local cultural groups. There are some indications that this type of material is beginning to dominate the site.

Historic photographs comprise much of the heritage content on KH. Most have only a brief line or two of description which is usually restricted to identifying individuals or locations depicted, without any further explanation of historical context. Quite a few of these photographs are without dates. They also generally lack any metadata indicating provenance, other than the historical society they have been collected by. Many of the private collections of clippings and photographs found on this site are similarly under-described. For instance, one family album uploaded in 2007 has blank space left around its images for the subsequent adding of explanatory text; six years on, this has yet to be completed. In some cases, these photographs are indicated to be part of a "topic" that links them to other material in KH. In other cases though, a system of informal and not always consistent tags provides the only principle of arrangement and connection with other content.

One example of a more systematically organized heritage topic is a dossier of individual items recounting the achievement of a local 15-year old who, in 1989, became the youngest person to swim across Cook Strait. This consists of 32 images and 26 documents (e.g. press releases and official letters of congratulations) that can be scrolled through as primary material relating to this story. Again however, apart from a single line of introduction and some brief captions, there is no accompanying text. Another example containing more contextual information is a set of photographs and diagrams depicting the early 20th Century construction of a local hydro-electricity scheme. This appears to have been put together by a local historian and may possibly be part of a book, although this is not made clear.

A number of items are digitized versions of printed publications (e.g. a 1988 booklet produced for a local school centenary). These publications have generally not been reproduced as PDFs. Hence the text is searchable but the original look is not maintained. In some cases, such as with the school centenary booklet, there has been an effort to indicate the way content was arranged on individual pages and the order of these in relation to one another. However, the integrity of the original publication is somewhat compromised by the fact that additional images and information have also been included and packaged together as a single item. In other cases, such as in newspaper supplements, different pieces of text and images have been reproduced as independent snippets, in ways that makes the relationship and continuities between items found in the originals difficult to trace. More straightforward is the presentation of shorter published material, examples of which include a story about a local pioneer aviator originally printed in an aviation magazine and what appears to be a newspaper article about an early 20th Century Maori politician. In the latter case however, neither the date nor original source of this article has been provided. Other examples of the wide variety of heritage content found on this site include a brief anecdote from someone who worked in the area as a taxi driver in the 1960s; an illustrated book-length memoir by a local farmer and public servant; and two well-written, well-referenced encyclopedia-style pieces about early 19th Century Maori conflict in the region contributed by a local historian. One potentially very useful set of primary resources digitized on this site is a set of Native Land Court minutes between 1866-1868 which is also viewable as a PDF.

There is a very noticeable presence by the Kete administrators on the comments threads. Some of these posts are credited to "Kete Administration"; others to individuals who identify themselves as representatives of KH. Of all the case study sites, KH definitely counts as the one that is most actively facilitated by administrators. This administrative input involves not only answering direct questions but also regularly thanking users for their contributions, actively inciting people to add more comments, suggesting avenues of further discussion and generally participating in the conversations. There is likewise evidence of administrators putting people in contact with one another 'behind the scenes' (e.g. through facilitating the exchange of contact details). Given KH's very strong emphasis on encouraging community involvement in its site, it does not seem all that surprising to find its administrators playing a much larger facilitative role than was the situation with the NLNZ case.

Analysis

Of all the case studies examined, KH is the one that is most strongly centered around participatory culture ideals. This is in terms of the extent to which it not only seeks to facilitate user-generated contents, but also user involvement in the development and display of its collections. KH employs a wiki format that invites anyone to have a say in how an item is edited or formatted. In terms of managing authority control issues, KH and its associated websites are the most institutionally self-effacing; whilst significantly, also the most administratively involved of the CHI sites examined.

To some degree KH can be considered the poster child of user-centric, community-based CHI websites in New Zealand. It has won awards and received much attention both in New Zealand and overseas, including the 2007 3M Award for Innovation in Libraries and the 2007 World Summit Awards: Special Mention (North America and Oceania) in the e-inclusion section. There are two obvious aspects where KH does not fare well in comparison with the other cases looked at. One is the overall quality of the writing and presentation of its content. One could argue that the lack of 'polish' or 'professionalism' in the writing might make the site unappealing as a resource for serious historical researchers. Also, the very small size of the image files used (often, of relatively poor quality) might also render them generally unsuitable for downloading and re-use. Such views are of course subjective, but those involved with KH would not necessarily dispute. Ransom's (2008) for instance, puts a lot of emphasis on "informality" and the need for the Horowhenua community to be able to express themselves on this site in their own way and in their own words, and indicating that the site is primarily intended to serve the needs of locals and not outsiders.

5.0 Summary

Despite the high level of interest in the potential usefulness of Web 2.0 for CHIs evident from the professional and academic literature, a scan of current New Zealand CHI websites indicates relatively low levels of Web 2.0 implementations of the kind that facilitates participatory culture. Instead, the social media applications most used by CHIs take the form of blogs, Twitter feeds and Facebook pages that are primarily aimed at promotional activities rather than fostering user-contributed contents and a sense of online community. In short, most CHIs are still using social media for less sophisticated forms of participation. There is evidence nevertheless that a considerable number of CHIs in New Zealand are using social media and in a handful of cases, they appear to be exploring the use of this media to facilitate participatory communication amongst their communities of interests. In this paper, two case studies were presented to highlight the differences between the less and more sophisticated forms of participation. The content analyses reveal notable differences between the cases as to the nature and extent of activities and user comments, especially in terms of whether these could be considered to add value through providing information or context missing from the original cultural contents. It needs to be noted that this study is primarily descriptive, not prescriptive and any initial recommendations offered are prefaced with a call for further empirical research and theoretical insights on this matter.

Overall, within the cases examined, only a very small proportion of items that are comments-enabled have comments attached; most of these have only one or two posts; and there are few signs of interactions between or amongst users. This does not necessarily mean there is a lack of public interest in using such features but it does indicate the CHIs are yet to fulfil their participatory culture potential.

The largest of the case studies, NLNZ on The Commons, is overwhelmingly comprised of brief 'fan mail' style appreciations (of a kind common on Flickr) that appear to offer little from a participatory culture or heritage engagement perspective. It is notable that the NLNZ on The Commons is hosted on a third-party social media platform that allow users to set up free accounts outside the regular constraints of approval processes through its own IT department. Social media use in this case is seemingly very much still in an early phase of informal experimentation. The experimentation occurs outside existing norms and standards of the institution's ICT use policies. This effort seems to fall within what Mergel and Bretschneider (2013) call 'decentralised, informal early experimentation' characterised by use of social media as a means of representing their agency as part of the social media channels their users and stakeholders are in but still testing out different approaches and operating in grey area and there is little coordination of the social media activities and user-generated contents in line with the institution's mission.

Overall, the direct ongoing involvement of site administrators appears comparatively low in terms of aspects such as providing instructional scaffolding, actively facilitating discussion, answering users' questions, responding to contributed information, etc. This is especially so with the national CHI websites (NLNZ on the Commons and other sites examined in the preliminary phase, e.g. NZHistory Online), where the use of Web 2.0 comes across as a minor, sideline initiative that is under-resourced and uncoordinated to the official institutional mission. While Flickr The Commons promotes itself as a crowdsourcing resource for CHIs to enhance their collections, NLNZ's use of it appears to be more about widening exposure of items and raising its institutional profile. These are in themselves important goals but this nevertheless indicates a gap between participatory culture rhetoric and reality. This highlights that a 'build it and they will come' approach, i.e. simply putting in place a Web 2.0 platform does not guarantee activities; let alone participation. So, the questions, 'If they come, will they participate?' and 'If they participate, will we (the institution concerned) do the same?' will also need to be considered.

By contrast the regional, community-initiated CHIs appear more committed to fostering community involvement in their collections. KH, for instance shows promising signs of a more coordinated effort in leveraging community knowledge and fostering participatory culture around their heritage contents. It is an example demonstrating how social media can be used to shift curatorial communication from one-to-many to a many-to-many communication whereby curatorial knowledge acts as a hub around which an online community of interest can build. By promoting user-contributed/generated content around its collection, KH enables cultural participants to be not just consumers, but also potential critics and creators of digital culture.

However, for small organisations, under-resourcing appears to be a major problem to sustain social media efforts. On 27 November 2013, an address was made to the New Zealand National Digital Forum by Ransom, to draw attention to a 'crisis', i.e. that there was a need for an upgrade to Kete to avoid security risks to the digital assets and community contributed contents (including those generated on KH), but there is no sustainable financial model to support this. This was unfortunate but not surprising news. Indeed, as rewarding as engagement with Web 2.0 communities can be, many CHIs (especially those at the local-, community-level) lack dedicated funding, human resources and an infrastructure needed to not only get them off the ground but to sustain them once developed (Jett, et al., 2010).

6.0 Conclusion and indication of further research

In the conclusion to her book, Theimer (2011) re-emphasised that Archive 2.0 should not be thought of simply as the sum of 'Archive + Web 2.0'. She proposes that the transformation of archival practice in the age of social media should be about facilitating a mind-set amongst archivists that is focused around openness, user-centeredness and flexibility rather than simply about deploying a technology. This would apply to other CHIs. Most CHIs are still a long way from reinventing themselves through new technologies and media, in making their collections open to the public to use, repurpose and re-contextualise in a way that promotes interactivity, engagement and knowledge co-construction and exchange. Nevertheless, an increasing number of these memory institutions are moving into that direction even though at the moment, the overall use of Web 2.0 applications by CHIs to foster participatory culture, if any, appears to be something that is still very much in an informal, experimental phase.

On-going changes in technology, as well as a tentative, exploratory approach by CHIs unsure of the degree to which they wish to commit to participatory culture, and how this might impact on their practice, means that there are at present an ever-evolving variety of ways and purposes of engaging in this area. Similarly, while there is a rapidly growing body of literature around the topic of participatory culture, this is spread relatively thinly across a large number of disciplines with different interests and orientations. Consequently, there seems at the moment, insufficient coherence in terms of focused definitions and discussion of best practice.

The case studies conducted in this study have proven useful in terms of providing a detailed, informative snapshot of what is presently happening in New Zealand CHIs social media initiatives, with a particular focus on the extent of participatory culture established. Further, by taking a methodological approach that provides a close analysis of the actual character of user-generated and contributed contents, as well as the patterns of links between comments posted by users and between site administrators and users, these case studies address what has been identified as a significant research need by other researchers (Yakel, 2011) . The study also highlights the need to address many remaining questions. There is no doubt that social media present its own set of issues and challenges as well. This paper concludes by drawing attention to a number of issues needing investigation.

The fact that more people can now produce and disseminate contents (including cultural objects) rather than just interpreting them means that institutions and individuals who have traditionally been a part of this production processes are having to adapt to this new mode of production. We are now seeing 'ordinary citizens and users' being included in cultural processes that were once solely the domain of collection managers, curators and other experts, often attached to institutions. This is not a challenge unique to the heritage discipline. Other examples that have illustrated this shift and need to adapt include those of citizen journalism, online activism and in art production — there is the deviantART example which claims to be "The world's largest online art community".

In addition to operational barriers such as limited funding and resources, introducing participatory processes into CHI practices has also raised some concerns around authority, liability and credibility (Yakel, 2011). The relationship between experts and non-experts and the processes though which CHIs use and make sense of user-generated and contributed content have yet to be resolved. Separation of folksonomy from the 'official finding aid' is ubiquitous in Archives 2.0 for instance and this separation appears to be a way institutions use to 'protect' the authority of the finding aids (and perhaps, of the institutions). This appears to be the case with the NLNZ on The Commons examined in this study.

For Munster and Murphie (2009), while the '2.0' characteristics of 'participatory', 'dynamic' and 'user-centred' are presented as positives that sell Web 2.0 to general users and to excite us with enticements of the possible features they promise, these features are often offered within the framework of business and marketing. They argue therefore that on one hand, Web 2.0 promises user empowerment, on the other hand, it threatens control and exploitations.

It may also be possible that an institution's willingness to engage in participatory communication via social media, or lack thereof is already established and embedded within its organisational culture or the associated occupational culture. Along with 'radical trust' (Fichter, 2006), a concept that is gaining currency within the social media debate, it would be useful to study the influence of organisational and occupational cultures on institutions' social media practices and an institution's inclination to 'control and exploit' or to 'trust and include' its community.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Victoria University of Wellington — University Research Fund 107851 for the undertaking of this research and the research assistance provided by Reid Perkins.

Notes

1 Email correspondence from Reuben Schrader, Web editor of the National Library of New Zealand on 5 December 2012.

References

[1] Andrejevic, M. (2011). Social network exploitation. In Papacharissi, Z. (Ed.) A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites. New York: Routledge, (pp.82—102).

[2] Bernstein, S. (2008). Top 10 Reasons The Commons on Flickr is Awesome.

[3] Bruns, A. (2009). From prosumer to produser: understanding user-led content creation. Paper presented at Transforming Audiences, London, 3-4 September, 2009.

[4] Chad, K. and Miller, P. (2005). Do libraries matter? The rise of Library 2.0.

[5] Chan, S. (2008). Commons on Flickr — a report, some concepts and a FAQ — the first 3 months from the Powerhouse Museum, Fresh & New(er).

[6] Cocciolo, A. (2010). Can Web 2.0 enhance community participation in an institutional repository? The case of PocketKnowledge at Teachers College, Columbia University. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(4), 304-312.

[7] Daines, J. G. and Nimer, C. L. (2009). Web 2.0 and Archives. The Interactive Archivist: Case studies in utilizing Web 2.0 to improve the archival experience.

[8] Falk, J. H. (2006). An identity-centered approach to understanding museum learning. Curator: The Museum Journal, 49, 151—166. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2006.tb00209.x

[9] Fichter, D. (2006). Web 2.0, library 2.0 and radical trust: A first take.

[10] Flinn, A. (2010). An attack on professionalism and scholarship?: Democratising archives and the production of knowledge. Ariadne, 62.

[11] Freeman, C. G. (2010). Photosharing on Flickr: Intangible heritage and emergent publics. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16 (4), 352—368. http://doi.org/10.1080/13527251003775695

[12] Gurian, E. H. (2006). Civilizing the museum: The collected writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. London: Routledge.

[13] Henman, E. (2011). Analyzing Flickr the Commons (Part 2).

[14] Huvila, I. (2008). Participatory archive: Towards decentralized curation, radical user orientation, and broader contextualization of records management. Archival Science, 8(1), 15-36. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-008-9071-0

[15] Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York University Press.

[16] Jett, J., Palmer, C.L., Fenlon, K., & Chao, Z. (2010). Extending the reach of our collective cultural heritage: The IMLS DCC Flickr Feasibility Study. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science & Technology, 47.

[17] Johnston, C. (2008). Awesome photo — thanks!! Or, what I've learnt from our Flickr pilot in LibraryTechNZ. (Blog).

[18] Krause, M. and Yakel, E. (2007). Interaction in virtual archives: The Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections next generation finding aid. The American Archivist, 70(2), 282-314.

[19] Lovinck, G. (2012). Networks without a cause: A critique of social media. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

[20] Mergel, I. and Bretschneider, S. I. (2013). A three-stage adoption process for social media use in government. Public Administration Review, 73, 390—400. http://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12021

[21] Miller, F. (2012). Time Flies! Celebrating 4 Years of The Commons on Flickr. (Blog).

[22] Munster, A. and Murphie, A. (2009). Editorial—Web 2.0: Before, during and after the event, Fibreculture Journal, 14.

[23] Nogueira, M. (2010). Archives in Web 2.0: New opportunities. Ariadne, 63.

[24] Oomen, J. and Aroyo, L. (2011). Crowdsourcing in the cultural heritage domain: Opportunities and challenges. http://doi.org/10.1145/2103354.2103373

[25] Palmer, J. and Stevenson, J. (2011). Something worth sitting still for? Some implication of Web 2.0 for Outreach. In Theimer, K. (Ed.) (2011). A Different Kind of Web: New Connections between Archives and Our Users. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, (p.2).

[26] Palmer, C.L., Zavalina, O., &anp; Fenlon, K. (2010). Beyond size and search: Building contextual mass in digital aggregations for scholarly use. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science & Technology, 47.

[27] Proctor, N. (2010). Digital: Museum as platform, curator as champion, in the age of social media. Curator: The Museum Journal, 53(1), 35-43. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2009.00006.x

[28] Ransom, J (2008). Kete Horowhenua : the story of the district as told by its people. Presented at the 2008 VALA Conference, Mebourne, 5-7 February 2008.

[29] Russo, A., Watkins, J., Kelly, L. and Chan, S. (2008), Participatory Communication with Social Media. Curator: The Museum Journal, 51, 21—31. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2008.tb00292.x

[30] Samouelian, M. (2009). Embracing Web 2.0: Archives and the newest generation of web applications. The American Archivist, 72, 42-71.

[31] Shilton, K. and Srinivasan, R. (2007). Participatory appraisal and arrangement for multicultural archival collections. Archivaria, 63, 87-101.

[32] Tennant, R. (2010). Tragedy of the (Flickr) Commons? The Digital Shift.

[33] Terras, M. (2011). The Digital Wunderkammer: Flickr as a platform for amateur cultural and heritage content. Library Trends, 59(4), 686—706. http://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0022

[34] Theimer, K. (Ed.). (2011). A Different Kind of Web: New Connections between Archives and Our Users. Chicago: Society of American Archivists.

[35] van den Akker, C., et al. (2011). Digital Hermeneutics: Agora and the online understanding of cultural heritage.

[36] Yakel, E. (2011). Balancing archival authority with encouraging authentic voices to engage with records. In Theimer, K. (Ed.) (2011). A Different Kind of Web: New Connections between Archives and Our Users. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, (pp. 75—101).