|

D-Lib Magazine

July/August 2014

Volume 20, Number 7/8

Table of Contents

Realizing Lessons of the Last 20 Years: A Manifesto for Data Provisioning & Aggregation Services for the Digital Humanities (A Position Paper)

Dominic Oldman, British Museum, London

Martin Doerr, FORTH-ICS, Crete

Gerald de Jong, Delving BV

Barry Norton, British Museum, London

Thomas Wikman, Swedish National Archives

Point of Contact: Dominic Oldman, doint@oldman.me.uk

doi:10.1045/july2014-oldman

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC CRM), is a semantically rich ontology that delivers data harmonisation based on empirically analysed contextual relationships rather than relying on a traditional fixed field/value approach, overly generalised relationships or an artificial set of core metadata. It recognises that cultural data is a living growing resource and cannot be commoditised or squeezed into artificial pre-conceived boxes. Rather, it is diverse and variable containing perspectives that incorporate different institutional histories, disciplines and objectives. The CIDOC CRM retains these perspectives yet provides the opportunity for computational reasoning across large numbers of heterogeneous sources from different organisations, and creates an environment for engaging and thought-provoking exploration through its network of relationships. The core ontology supports the whole cultural heritage community including museums, libraries and archives and provides a growing set of specialist extensions. The increased use of aggregation services and the growing use of the CIDOC CRM has necessitated a new initiative to develop a data provisioning reference model targeted at solving fundamental infrastructure problems ignored by data integration initiatives to date. If data provisioning and aggregation are designed to support the reuse of data in research as well as general end user activities then any weaknesses in the model that aggregators implement will have profound effects on the future of data centred digital humanities work. While the CIDOC CRM solves the problem of quality and delivering semantically rich data integration, this achievement can still be undermined by a lack of properly managed processes and working relationships between data providers and aggregators. These relationships hold the key to sustainability and longevity because done properly they encourage the provider to align their systems, knowing that the effort will provide long lasting benefits and value. Equally, end user projects will be encouraged to cease perpetuating the patchwork of short-life digital resources that can never be aligned and which condemn the digital humanities to a pseudo and predominantly lower quality discipline.

Introduction

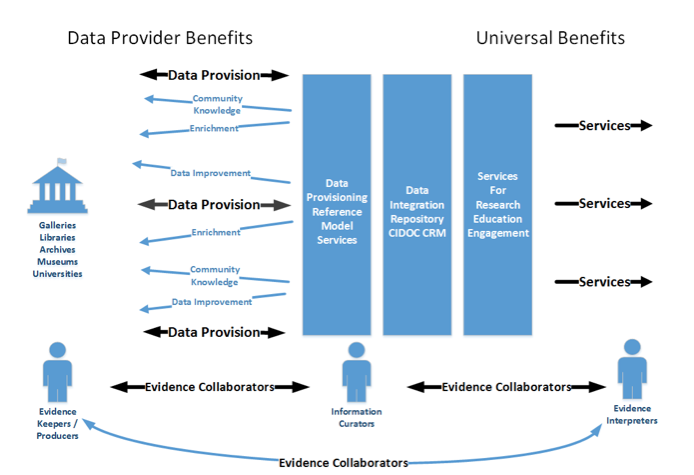

This paper addresses the complex issues of large scale cultural heritage data integration crucial for progressing digital humanities research and essential to establishing a new scholarly and social relevance for cultural heritage institutions often criticised for being, "increasingly captive by the economic imperatives of the marketplace and their own internally driven agendas1." It includes a discussion on the essential processes and necessary organisational relationships, data quality issues, and the need for wider tangible benefits. These benefits should extend beyond end user reuse services and include the capability to directly benefit the organisations that provide the data, providing a true test of quality and value. All these components are interdependent and directly affect the ability of any such initiative to provide a long term and sustainable infrastructure on which evidence producers, information curators and evidence interpreters can rely on, invest in and further develop. Many cultural data aggregation projects have failed to address these foundational elements contributing instead to a landscape that is still fragmented, technology driven and lacking the necessary engagement from humanities scholars and institutions. Therefore this paper proposes a new reference model of data provision and aggregation services2 aiming to foster a more attractive and effective practice of cultural heritage data integration from a technological, managerial and scientific point of view.

This paper is based on results and conclusions from recent work of the CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group (CRM SIG), a working group of CIDOC, the International Committee for Documentation of the International Council of Museums (ICOM). The Group has been developing the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (Doerr, 2003; Crofts et al., 2011) and been providing advice for integration of cultural heritage data over the past 16 years. Over this period the adoption of the CIDOC CRM has significantly increased, supported by enabling technology such as RDF stores3 and systems like SolrTM4, with Graph5 databases providing further potential6. These systems have become mature and powerful enough to deal with the real complexity and scale of global cultural data. Consequently, this means that issues of sustainable management of integrated resources are more urgent that ever before, and consequently the Group is calling for a collaborative community effort to develop a new Reference Model of Data Provision and Aggregation, which is based on a completely different epistemological paradigm compared to the well-known OAIS (Open Archival Information Service) Reference Model (Consultative Committee for Space data Systems, 2009). Therefore, this paper reflects positions developed within the CRM SIG and by others on three important aspects of developing integrated cultural heritage systems and associated data provisioning processes. These positions in summary are:

- Cultural heritage data provided by different organisations cannot be properly integrated using data models based wholly or partly on a fixed set of data fields and values, and even less so on 'core metadata'. Additionally, integration based on artificial and/or overly generalised relationships (divorced from local practice and knowledge) simply create superficial aggregations of data that remain effectively siloed since all useful meaning is available only from the primary source. This approach creates highly limited resources unable to reveal the significance of the source information, support meaningful harmonisation of data or support more sophisticated use cases. It is restricted to simple query and retrieval by 'finding aids' criteria.

- The same level of quality in data representation is required for public engagement as it is for research and education. The proposition that general audiences do not need the same level of quality and the ability to travel through different datasets using semantic relationships is a fiction and is damaging to the establishment of new and enduring audiences.

- Thirdly, data provisioning for integrated systems must be based on a distributed system of processes in which data providers are an integral part, and not on a simple and mechanical view of information system aggregation, regardless of the complexity of the chosen data models. This more distributed approach requires a new reference model for the sector. This position contrasts with many past and existing systems that are largely centralised and where the expertise and practice of providers is divorced.

The effects of these issues have been clearly demonstrated by numerous projects over the last 20 years and continue to affect the value and sustainability of new aggregation projects, and therefore the projects that reuse the aggregated data. This paper is therefore particularly aimed at new aggregation projects that plan to allocate resources to data provisioning and aggregation and that wish to achieve sustainability and stability, but also informs existing aggregators interested in enhancing their services.

Background

During the last two decades many projects have attempted to address a growing requirement for integrated cultural heritage data systems. By integrating and thereby enriching museum, library and archive datasets, quality digital research and education can be supported making the fullest use of the combined knowledge accumulated and encoded by cultural heritage organisations over the last 30 years — much of this effort having been paid for by the public purse and by other humanities funding organisations. As a result the potential exists to restore the significance and relevance of these institutions in a wider and collaborative context revitalising the cultural heritage sector in a digital environment. The ability to harmonise cultural heritage data such that individual organisational perspectives and language is retained, yet at the same time allowing these heterogeneous datasets to be computationally 'reasoned' over as a larger integrated resource, is one that has the potential to propel humanities research to a level that would attract more interest and increased investment. Additionally, the realisation of this vision provides the academy with a serious and coherent infrastructural resource that encodes knowledge suitable as a basis for advanced research and crucially, from a Digital Humanities7 perspective, based upon cross disciplinary practices. As such it would operate to reduce the intellectual gap that has opened up between the academy and the cultural heritage sector.

Even though industrial and enterprise level information integration has a successful 20 year history (Wiederhold, 1992; Gruber, 1993; Lu et al., 1996.; Bayardo et al., 1997; Calvanese, Giacomo, Lenzerini, et al., 1998), to date very few projects, if any, attempting to deliver such an integrated vision for the cultural heritage sector have been able to preserve both meaning and provide a sustainable infrastructure under which organisations could realistically align their own internal infrastructures and processes. Systems have lacked the necessary benefits and services that would encourage longer-term commitment, failed to develop the correct set of processes needed to support long-term data provisioning relationships, and neglected to align their services with the essential objectives of their providers. The situation reflects a wider problem of a structurally fragmented digital humanities landscape and an ever-widening intellectual gap with cultural heritage institutions, reflected rather than resolved by aggregation initiatives.

This is despite the existence of very clear evidence (lessons learnt during the execution of these previous projects) for the reasons behind this failure. The three main lessons that this paper identifies are:

- The nature of cultural heritage data (museum collection data, archives, bibliographic materials but also more specialist scientific and research datasets) is such that it cannot be treated in the same way as warehouse data, administrational information or even library catalogues. It contains vast ranges of variability reflecting the different types of historical objects with their different characteristics, and therefore is also influenced by different scholarly disciplines and perspectives. Different institutional objectives, geography and institutional history also affect the data.

There are no 'core' data.

However, many project managers use these characteristics to claim that such complexity cannot be managed, or conversely that such rich data does not exist, or that it is impossible to create an adequate common data representation. These positions hinder research and development and limit engagement possibilities.

- There is a frequent lack of understanding that cultural heritage data cannot be carved up into individual products to be shipped around, stored and individually 'consumed', like a sort of emotion stimulant coming to "fruition"8. Heritage data is rather the insight of research about relationships between a past reality and current evidence in the form of curated objects. Therefore it is only meaningful as long as the provenance and the connection to the material evidence in the hands of the curators are preserved. The different entities that exist within it are fundamentally related to each other providing mutually dependent context. Heritage data is subject to continuous revision by the curators and private and professional researchers, and must reliably be related to previous or alternative opinions in order to be a true source of knowledge. Consequently, the majority of the data in current aggregation services, sourced from cultural heritage organisations, cannot be cited scientifically.

- Sustaining aggregations using data sources from vastly different owning organisations requires an infrastructure that facilitates relationships with the local experts and evidence keepers to ensure the correct representation of data (such that it is useful to the community but also to the providing organisations themselves), and also takes into account the changing nature of on-going data provision. Changes can occur at either end of data provisioning relationships and therefore a system must be able to respond to likely changes, taking into account the levels of resources available to providers necessary to maintain the relationship throughout. Aggregations must also include processes for directly improving the quality of data (i.e. using the enriched integrated resources created by data harmonisation) and feeding this back to institutional experts.

These three issues are inextricably linked. Understanding the meaning of cultural heritage data and the practices of the owners of the data or of material evidence are essential in maintaining long term aggregation services. Longevity requires that data must be encoded in a way to provide benefits for all parties; the users of resulting services, the aggregators and the providers. Due to the same functional needs such principles are self-evident for instance, for the biodiversity community, expressed as the "principle of typification" for zoology in (ICZN, 1999) and its application in the collaboration of GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) within natural history museums, but they are not evident for the wider cultural heritage sector. This may be because, in contrast to cultural heritage information, misinterpretation of biodiversity data can have immense economic impact, for instance, with pest species. By not addressing these problems only short-lived projects can result that, in the end, consume far more resources than resolving these issues would require.

The Historical Problem

Consider this statement from 1995:

"Those engaged in the somewhat arcane task of developing data value standards for museums, especially the companies that delivered collections management software, have long had to re-present the data, re-encode it, in order for it to do the jobs that museums want it to perform. It's still essentially impossible to bring data from existing museum automation systems into a common view for use for noncollections management purposes as the experience of the Museum Educational Site Licensing (MESL) and RAMA (Remote Access to Museum Archives) projects have demonstrated. Soon most museums will face the equally important question of how they can afford to re-use their own multimedia data in new products, and they will find that the standards we have promoted in the past are inadequate to the task." (Bearman, 1995)

Both the projects cited in the quote are testament to the fact that managing data and operational relationships with cultural heritage organisations in support of collaborative networks is a complicated undertaking and requires a range of different skills. Some of the issues have been clarified and resolved by the passage of time and we now have a better understanding of what benefits are practically realistic and desirable when forming new data collaborations. Yet new projects seem intent on replicating flawed approaches and repeating the mistakes of the past.9

The Continuing Problem

Consider this opinion from the JISC Discovery Summit 2013 from the expert panel.

"...developers are impatient and just want to get access to the data and do interesting things, and on the other side of the equation we have curators reasonably enough concerned about how that data is going to be used or misinterpreted or used incorrectly. I think that this is actually a difficult area because the conceptual reference models are generally more popular with the curators than with the developers [...It is not] clear to me ... how we solve the problem of engaging the people who want to do the development...through that mechanism, but nonetheless as this great experiment that we are living through at the moment with opening up data and seeing what can be done [...]unfolds, if we find that the risks are starting to become too great and the value is so poor because the data is being misused or used incorrectly or inappropriately, if that risk is a risk to society in general and not just to the curators...then we are going to have to find those kind of solutions." (JISC, 2013)10

This suggests a continuing problem and that digital representation of cultural heritage information is still determined by those who understand it least. It also suggests that cultural heritage experts have yet to engage with the issue of digital representation and continue to leave it to technologists. Nevertheless, why would a software developer believe that representing the semantics and contextual relationships between data is not as interesting (let alone crucially important) as representing data without them, and why do they determine independently the mode of representation in any event? Given the enormous costs involved in aggregating European data such a risk assessment suggested above, might reasonably be conducted up front, since the infrastructural changes needed to resolve the realisation of this risk would be almost impossible to implement. The delegates of the Summit agreed by a large majority that their number one concern was quality of metadata and contextual metadata, contrary to the view of some of the panel members11 — emphasising the gap between providers, users and aggregators.

Ironically, it is those who advocate technology and possess the skills to use computers who seem most reluctant to explore the computer's potential for representing knowledge in more intelligent ways. As computer scientists regularly used to say, 'garbage in, garbage out' (GIGO)12. The value and meaning of the data should not be secondary or be determined by an intellectually divorced technological process.

Position 1 — The Nature of Cultural Heritage Data

The RAMA project, funded in the 1990s by the European Commission, serves as a case study demonstrating how squeezing data into fixed models results in systems that ultimately provide no significant progress in advancing cultural heritage or scholarly humanities functions. Yet large amounts of scarce resources are invested in similar initiatives that can only provide additional peripherally useful digital references. The most recent and prominent example is the Europeana project13, which although technologically different to RAMA, retains some of the same underlying philosophy. The RAMA project proceeded on the premise that data integration could only be achieved if experts were prepared to accept a, "world where different contents could be moulded into identical forms", and not if, "one thinks that each system of representation should keep its own characteristics regarding form as well as contents" (Delouis, 1993). This is a view that is still widely ingrained in the heads of many cultural heritage technologists. While more aggregations, like Europeana, have made some use of knowledge representation principles and event based concepts they continue to use them in highly generalised forms and with fixed, core field modelling. This is clearly wrong from both a scholarly and educational perspective (as well as for subsequent engagement opportunities) and therefore results in wasteful technical implementations. Yet academics seem unable to deviate (or fail to understand) from this traditional view of data aggregation.

The CIDOC CRM, which commenced development in the latter part of the 1990's post the failure of RAMA and MESL, is a direct answer to the "impossible" problem identified by Bearman and others. The answer, realised by several experts, was to stop the technically led pre-occupation with fixed values and fields which inevitable vary both internally and between organisations, and instead think about the relationships between things and the real world context of the data. This not only places emphasis on the meaning of the data but also places objects, to a certain degree, back into their historical context.

"Increasingly it seems that we should have concerned ourselves with the relationships...between the objects." (Bearman, 1995)

This fundamentally different approach concentrates on generalisations not determined by high committee but is instead based on many years of empirical analysis. It is concerned with contextual relationships that are mostly implicit but prominent in various disciplinary forms of digital documentation and associated research questions, and that cultural heritage experts in all fields are able to agree on. From this analysis a notion of context has been emerging which concentrates on interrelated events and activities connected to hierarchies of part-whole relationships of things, events and people, and things subject to chains of derivation and modification. This is radically different from seeking the most prominent values by which people are supposed to seek for individual objects.

This approach is highly significant for the digital humanities (see Unsworth (2002)) because it inevitably requires a collaborative shift of responsibilities from technologists to the experts who understand the data. It therefore also requires more engagement from museums and cultural heritage experts. However, the widening gap between the Academy and resource-poor memory institutions means that a solution requires clearly identified incentives to encourage this transfer of responsibility. It entails the alignment of different strategies and the ability to provide more relevant and useful services with inbuilt longevity. It must carry an inherent capacity to improve the quality of data and deliver all benefits cost effectively. Given this, the alignment needs to start at the infrastructure level.

The technical reasons why applications of the CIDOC CRM can be much more flexible, individual and closer to reality than traditional integration schemata, and yet allow for effective global access, are as follows. Firstly, the CRM extensively exploits generalization/specialization of relationships. Even though it was clearly demonstrated in the mid 1990's that this distinct feature of knowledge representation models is mandatory for effective information integration (Calvanese, Giacomo, Lenzerini, et al., 1998), it has scarcely been used in other schemata for cultural data integration14. It ultimately enables querying and access to all data with unlimited schema specializations but by fewer implicit relationships15, and removes the need to mandate fixed data field schemas for aggregation. This is also substantially different from adding 'application profiles' to core fields (e.g. schema.org), where none of the added fields will reveal the fact of a relationship in a more generic query. Secondly, it foresees the expansion of relationships into indirections, frequently implying an intermediate event, and the deduction of direct relationships from such expansions. For instance, the size of an object can be described as a property of an object or as a property of a measurement of an object. The location of an object can be property of the object or of a transfer of it. The expansion adds temporal precision. The deduction generalizes the question to any time, as a keyword search does. Modern information systems are well equipped to deal consistently with deductions, but no other documented schema for cultural data integration has made use of this capacity (Tzompanaki and Doerr, 2012; Tzompanaki et al., 2013). This paradigm shift means that, instead of the limitations imposed by using fixed fields for global access, the common interface for users is defined by an underlying system of reasoning that is invisible to the user (but is explicitly documented) and is crucially detached from the data entry format. It provides seemingly simple and intuitive generalizations of contextual questions. This use of algorithmic reasoning, that makes full use of the precise underlying context and relationships between entities, provides a far better balance and control of recall and precision and can be adjusted to suit different requirements.

By representing data using a real world semantic ontology, reflecting the practice and understanding of scholars and researchers, aggregation projects become more serious resources, and as a result their sustainability will become a more serious concern across the community. The enthusiasm of technologists and internal project teams is not sufficient for long-term sustainability, and corporate style systems integration techniques are not appropriate for cultural heritage data. Just like the proliferation of data standards, often justified by small variations in requirements, isolated aggregations using the same justifications will also proliferate affecting overall sustainability and diluting precious resources and financing. In contrast an aggregation that supports and works with the variability of cultural heritage data and owning organisations, and that services a wider range of uses, stands a far better chance of long-term support.

Other schemas, despite using elements of knowledge representation, are still created, 'top down' and perpetuate a belief in the need for 'core'; and are inevitably flawed by a lack of understanding of knowledge and practice. It is far easier and quicker for technologists to make artificial assumptions about data, and mandate a new schema, than it is to develop a 'bottom up' understanding of how cultural heritage data is used in practice. However, the CRM SIG has completed this work removing the need for further compromise on this field.

Position 2 — Engagement Needs Real World Context

A familiar argument put to the community by technologists is that creating resources using a semantic reference model is complicated and expensive, and that aggregations designed to satisfy a general audience do not need this level of sophistication. Moreover, the requirements of museum curators (see above) and other academics are not the same as those of the public and the latter should be prioritised when allocating resources to create services. In other words, publishing data, in whatever form, is the most important objective. However, publishing data and communicating understanding are two completely different concepts and humanities data can be impossible to interpret without meaningful context. This view also misunderstands the role of museums and curators who are keepers of primary material evidence and hold a primary role in communicating with and engaging general audiences using rich contextual narratives.

The only reference model that influences the design of current aggregation systems is the Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS). It basically assumes that provider information consists of self-contained units of knowledge, such as scholarly or scientific publications, finished and complete with all necessary references. It assumes that they are finished products that have to be fixed and preserved for future reference. The utterly unlucky choice of the term 'metadata', for cultural data, assuming that the material cultural object is the real 'data', actually degrades curatorial knowledge to an auxiliary retrieval function without scientific merit, as if one could 'read out' all curatorial knowledge just by contemplating the object, in analogy to reading a book. Consequently, a surface representation with limited resolution (a 3D Model) is taken as a sufficient 'surrogate' for the object itself, the assumed real target of submission to the Digital Archive. The absence of a different type of reference model perpetuates this view in implementer and management circles. In reality, 'museum metadata' are the product, but not as a self-contained book, but rather equivalents of paragraphs, illustrations, headings and references of a much larger, 'living' book — the network of current knowledge about the past. The same holds for other fields of knowledge, such as biodiversity or geology data.

Museum curators are skilful in representing objects using a range of different approaches, all of them more sophisticated than the presentation of raw object metadata. Their experience and practice has wider value for colleagues in schools, universities and other research environments. The reason why many curators have not engaged with technology is because of the limitations that it apparently presents in conveying the history and context in which objects were produced and used. Museums, by their nature, remove the object from its historical context and "replaces history with classification". Curators, almost battling against the forces of their own environment, attempt to return objects back into their own original time and space, a responsibility difficult to achieve within the "hermetic world" of the museum gallery (Stewart, 1993, p.152), and particularly amongst a largely passive and untargeted mixture of physical 'browsers'.

In the digital world flat data representations, even if augmented with rich multimedia, do not convey the same quality of message and validity of knowledge that curators attempt to communicate to general audiences every day. The lonely gallery computer with its expensive user experience and empty chair is all too often a feature of 'modern' galleries. Museums also spend vast amounts of money enriching data on their web sites, sometimes with the help of curators, and attempt to add this valuable and engaging context. However, such activity involves the resourcing of intensive handcrafted content that inevitably limits the level of sophistication and collaboration that can be achieved, as well as the range and depth of topics that can be covered. (Doerr and Crofts, 1998, p.1)

Far from being driven by purely private and scholarly requirements, curators would see contextual knowledge representation as a way of supporting their core role in engaging and educating the public but on a scale they could not achieve with traditional methods and with current levels of financing. Since semantically harmonised data reveals real world relationships between things, people, places, events and time, it becomes a more powerful engagement and educational tool for use with wider audiences beyond the walls of the physical museum. In comparison to traditional handcrafted web page development it also represents a highly cost effective approach.

Semantic cultural heritage data using the CIDOC CRM may not equate to the same type of narrative communication as a curator can provide, but it can present a far more engaging and sophisticated experience when compared to traditional forms of data representation. While it can help to answer very specific research questions it can also support the unsystematic exploration of data. It can facilitate the discovery of hitherto unknown relations and individual stories, supporting more post-modern concerns; but also providing a means to amalgamate specifics and individual items into a larger "totalizing" view of expanding patterns of history16 (Jameson, 1991, p.333).

Unsystematic exploration17 (but which invariably leads to paths of relationships around particular themes) is extremely useful for general engagement, but this is also seen as increasingly important for scholars (curators, researchers/scientists from research institutions and universities) working with big data, changing the way that scholars might approach research and encouraging new approaches that traditionally have been viewed as more appropriate to the layperson. The CIDOC CRM ontology supports these different approaches bringing together methodologies that are useful to researchers, experts, enthusiasts and browsers alike, but in a single multi-layered implementation.

The opportunity provided by the CIDOC CRM goes further. Just in the same way that lessons identified in the 1990's about cultural heritage integration have been ignored, the research into how museums might shape the representation of cultural knowledge has also been ignored in most digital representations. The pursuit of homogenised views with fixed schemas continues with vigour within digital communities, but the strength of the knowledge held by different museums is in its difference — its glorious heterogeneous nature. Yet again from the 1990s, a quote from a leading academic museologist.

"Although the ordering of material things takes place in each institution within rigidly defined distinctions that order individual subjects, curatorial disciplines, specific storage or display spaces, and artefacts and specimens, these distinctions may vary from one institution to another, being equally firmly fixed in each. The same material object, entering the disciplines of different ensembles of practices, would be differently classified. Thus a silver teaspoon made in the eighteenth century in Sheffield would be classified as 'Industrial Art' in Birmingham City Museum, 'Decorative Art' at Stoke on Trent, 'Silver' at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and 'Industry' at Kelham Island Museum in Sheffield. The other objects also so classified would be different in each case, and the meaning and significance of the teaspoon itself correspondingly modified". (Greenhill, 1992, pp.6-7)

While the World Wide Web has undoubtedly revolutionised many aspects of communication, work and engagement, its attractive but still essentially "Gutenberg" publishing model has effectively created an amnesia across the community. While a pre-Web world talked about how computers could push the boundaries of humanities as a subject, a post-Web world seems content with efficient replication of the same activities that previously took place on paper (Renn, 2006; McCarty, 2011, pp.5-6).

Position 3 — The Reality of Cultural Heritage Data Provisioning

It is a long-standing failure of aggregators to design and implement a comprehensive set of processes necessary to support long term provider-to-aggregator relationships. The absence of such a reference model is considered to be a major impediment to establishing sustainable integrated cultural heritage systems and therefore, by implication, a significant factor in the inability to fully realize the benefits of the funding and resources directed towards the humanities over the last 20 years. This legacy has contributed to a general fragmentation of humanities computing initiatives as project after project has concentrated on end user functionality without properly considering how they could sustain the relationships that ultimately determined their shelf life — if indeed this was an objective. This, along with the lack of an empirically conceived cultural heritage reference model (discussed above), has impeded the ultimate goal of collaborative data aggregation to support intelligent modelling and reasoning across large heterogeneous datasets, and provide connections between data embedded with different perspectives. Instead, each new and bigger initiative pushes further the patience of funders who are increasingly unhappy with the return to the community of their investment.

In contrast to the approach of most aggregators, the responsibilities demanded of such systems are viewed by this paper from a real world perspective, as distributed and collaborative rather than substantially centralized and divorced from providers, as the OAIS Reference Model assumes. In reality the information provider curates his/her resources and provides, at regular intervals, updates. The provider is the one who has access to the resources to verify or falsify statements about the evidence in their hands. Therefore the role of the aggregator includes the responsibility for the homogeneous access to the integrated data and the resolution of co-references (multiple URIs, 'identifiers', for the same thing) across all the contributed data - but not to 'take over' the data like merchandise. The latter synopsis of consistency appears to be the genuine knowledge of the aggregator, whereas any inconsistencies should be made known to, and can only be resolved by, the original providers.

The process of transformation of these information resources to the aggregator's target system requires a level of quality control that is often beyond the means of prospective providers. Therefore a collaborative system that delivers such controls means that the information provider benefits from data improvement and update services that would normally attract a significant cost, and could not be done as effectively only based on local knowledge. Additionally, if the aggregation is done well, harmonisation should deliver significant wider benefits to the provider (including digital relevance and exposure for organisations regardless of their status, size and location) and to the community and society as a whole.

The process of mapping from provider formats to an aggregator's schema needs support from carefully designed tools. All current mapping tools basically fail in one way or another to support industrial level integration of data,

- from a large number of providers,18

- in a large number of different formats and different interpretations of the same formats,19

- undergoing continuous data and format changes at the provider side,

- undergoing semantic and format changes at the aggregator side20.

To consistently maintain integrated cultural data requires a much richer, component and workflow based architecture. The proposed architecture includes a new component, a type of knowledge base or 'mapping memory', and at its centre a generic, human readable 'mapping format' (currently being developed as X3ML)21, designed to support different processes and components and accommodate all organisations with different levels of resourcing. Such architecture begins to overcome the problem of centralised systems where mapping instructions are unintelligible and inaccessible to providers22 and hence lack quality control. Equally, it overcomes the problem of decentralised mapping by providers which often interpret concepts within the aggregator's schema in mutually incompatible ways. It finally overcomes the problem of maintaining mappings after changes to source or target formats and changes of interpretations of target formats or of terminological resources on which mappings are conditional. It should further provide collaborative communication (formal and social) support for the harmonization of mapping interpretations. Since the mapping process depends on clean data and brings to light data inconsistencies, sophisticated feed-back processes for data cleaning and identifier consistency between providers must also be built into the design.

The ambition of such an architecture exceeds the scope of typical projects and it can only come to life if generic software components can be brought to maturity by multiple providers. Unfortunately, all current 'generic' mapping tools are too deeply integrated into particular application environments and combine too many functions in one system to contribute to an overall solution. We do not expect any single software provider to be capable of providing such generic components for all the necessary interface protocols. This is borne out by the continued expenditure of many millions of Euros by funding bodies to fund mapping tools and other components in dozens of different projects without ever providing a solution of industrial strength and high quality.

Therefore the proposed architecture and reference model (called Synergy), which has already been outlined by the CRM SIG in various parts23, aims at a specification of open source components, well-defined functionality and open interfaces. Implementers may develop and choose between functionally equivalent solutions with different levels of sophistication, for example table-based, or graph-based visualization of mapping instructions, intelligent systems that automatically propose mappings or purely manual definition, etc. They may choose functionally equivalent components from different software providers capable of dealing with particular format and interface protocols and therefore different provider-aggregator combinations. Only in this way does the community have a chance to realize an effective data aggregation environment in the near future. In the reference model that we propose the architecture plays a central role and is a kind of proof of feasibility. However, it is justified and complemented by an elaborate model of the individually identified business processes that exist between the partners of cultural data provision and aggregation initiatives, both as a reference and a means to promote interoperability on an organisational and technical level.

The processes enabled by this architecture should also be viewed with an understanding that, as a result of a properly defined end-to-end provisioning system, other more collaborative processes and practices can be initiated that enable organizations to support each other and to exchange experience and practice more easily and to greater effect. The establishment of a system that supports many different organisations promotes greater levels of collaboration between them independently of aggregators, and increases the pool of knowledgeable resources. It is at this level where structural robustness can be practically implemented to enable a re-construction of the essential alliances between the cultural heritage sector and the wider academic body.

These considerations should be considered a priority for any new aggregation service rather than a problem to be solved at a later date. Prioritisation of quantity above quality and longevity means that aggregators soon reach a point where they can no longer deal adequately with data sustainability issues. The solution is often to concentrate even more resources on functionality and marketing in a hope that the underlying problem might be solved externally, and make the decision to remove funding more difficult. Inevitably relationships between providers and aggregators start to fail, links become broken and relationships break down leading to a gradual decline and finally failure. The cultural heritage sector is unable to invest resources into schemes that have unclear longevity and which lack the certainty needed to support institutional planning. Without a high degree of certainty cultural organisations cannot divert resources into aligning their own systems with that of aggregators and therefore the scope of those systems becomes so low that their overall value is marginal. Organisations become ever more cautious towards these new projects.

This current state of affairs is also implicitly reflected by the growth of smaller and more discrete projects that seek to aggregate data into smaller, narrower and bespoke models designed as index portals for particular areas of study and particular research communities. These projects can be interpreted as a direct statement of dissatisfaction with larger more ambitious aggregation projects that have failed to provide infrastructures onto which these communities can build and develop (and therefore contribute to an overall effort) extensions for particular areas of scholarly investigation. However, the reduced and narrow scope of these projects mean that they are only of use to those who already have a specialised understanding of the data, can piece together information through their own specialist knowledge, and are content with linear reference resources. They embrace concepts of linked data but forego the idea that a more comprehensive and contextual collaboration is possible.

To more cross-disciplinary researchers and other groups interested in wider and larger questions, the outputs of these projects are of limited interest and represent a fragmented patchwork of resources. They provide little in the way of information that can be easily understood or which easily integrates with other initiatives because they provide only snippets, data products that have been separated from their natural wider context and, in effect, they practically restrict (in contrast to their stated aims) the ability to link data outside their narrow domain. This severely limits the possibilities and use cases for the data and contributes to a fragmented landscape over which wider forms of digital humanities modelling is impossible.

Conclusion

Knowledge Representation

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, much effort was spent trying to both define and predict the trajectory of what had now been termed the digital humanities24.

"In some form, the semantic web is our future, and it will require formal representations of the human record. Those representations — ontologies, schemas, knowledge representations, call them what you will — should be produced by people trained in the humanities. Producing them is a discipline that requires training in the humanities, but also in elements of mathematics, logic, engineering, and computer science. Up to now, most of the people who have this mix of skills have been self-made, but as we become serious about making the known world computable, we will need to train such people deliberately." (Unsworth, 2002)

The debate about the extent to which humanists must learn new skills still continues today. The reasons why humanists have been slow and reluctant to incorporate these new skills into their work, in perhaps the same way that some other disciplines have done, are too varied and complex to consider here. Whether a lack of targeted training or a philosophical position about the extent to which computers can address the complexities of historical interpretation, or a lack of understanding about the areas of scholarship that can be enhanced or transformed by computers, the resulting lack of engagement seriously affects the outcomes and value of digital humanities projects. While there are notable exceptions the overwhelming body of 'digital humanities' work, while often providing some short term wonderment and 'cool', has not put the case well enough to persuade many humanists to replace existing traditional practices. This has a direct connection with the reasons why, despite a clear identification of the problem from different sources, flawed approaches still exist and are incorporated, without challenge, into each new technological development. The cultural heritage linked data movement currently provides new examples of this damaging situation.

Far from providing meaningful linking of data, the lack of a properly designed model reflecting the variability of museum and other cultural data, and the inability to provide a robust reference model for collaborative data provisioning mean that early optimism has not materialised into a coherent and robust vision. While more data is being published to the Internet it has limited value beyond satisfying relatively simple publishing use cases or providing reference materials for discrete groups. While these resources are useful, their preoccupation has seriously impeded more ground-breaking humanities research that might uncover more profound discoveries and demonstrate that humanities research is as important to society as scientific research, and is deserving of more consideration from funders. However, just as in scientific research, the humanities community must learn from previous research to be considered worthy of increased attention. Further fragmentation and unaligned initiatives are unlikely to instil confidence in those organisations that have previously been willing to finance digital humanities projects.

We must learn from projects like CLAROS25 at Oxford University that are significant because, while they adopt a more semantic and contextual approach, they have evolved from the lessons learnt directly from projects like RAMA. The CLAROS team includes expertise and experience derived through past contributions to the RAMA project, as well as others similar projects. This experience has provided a first-hand understanding of the problems of data aggregation and larger scale digital humanities research. As a result the CLAROS project positively benefits from the failures of previous research rather than replicates unsuccessful methodologies. New projects like ResearchSpace26 and CultureBrokers27, are now building on the work of CLAROS to create interactive semantic systems together with other types of CRM based projects.

Research and Engagement

While different audiences have different objectives all data use cases benefit from the highest quality of representation, the preservation of local meaning and the re-contextualising of knowledge with real world context. Researchers benefit from the ability to investigate and model semantic relationships and the facility to use context and meaning for co-reference and instance matching. Engagement and education activities benefit from exactly the same semantic properties that bring data to life and provide more interesting and varied paths for people to follow without the 'dead ends' that would ordinarily confront users of traditional aggregation services.

There is no longer an excuse for using 'top down' schemas because the 'bottom up' empirical and knowledge based approach is now available (the result of years of considerable effort) and accessible in the form of the CIDOC CRM. The core CRM schema is mature and stable, growing in popularity and provides no particular technological challenge. It is an object-oriented schema based on real world concepts and events implementing data harmonisation based on the relationships between things rather than artificial generalisations and fixed field schemas. It simplifies complicated cultural heritage data models but in doing so provides a far richer semantic representation sympathetic to the data and the different and varied perspectives of the cultural heritage community.

Reversing Fragmentation and Sustaining Collaboration

The history of digital humanities is now littered by hundreds of projects that have made use of and brought together cultural heritage data for a range of different reasons. Yet these projects have failed to build up any sense of a coherent and structural infrastructure that would make them more than "bursts of optimism" (Prescott, 2012). This seems connected with a general problem of the digital humanities clearly identified by Andrew Prescott and Jerome McGann.

"... the record of the digital humanities remains unimpressive compared to the great success of media and culture studies. Part of the reason for this failure of the digital humanities is structural. The digital humanities has struggled to escape from what McGann describes as 'a haphazard, inefficient, and often jerry-built arrangement of intramural instruments, free-standing centers, labs, enterprises, and institutes, or special digital groups set up outside the traditional departmental structure of the university'" (Prescott, 2012; McGann, 2010)

But while these structural failings exist in the academic world, Prescott also identifies years of exclusion of cultural heritage organisations, keeping them at arm's length and thereby contributing to a widening gap with organisations that own, understand and digitise (or, increasingly, curate digital material) our material, social and literary history. Prescott, with a background that includes both academic and curatorial experience in universities, museums and libraries, is highly critical of this separation and comments that, "my time as a curator and librarian [was] consistently far more intellectually exciting and challenging than being an academic". This experience and expertise, which in the past set the tone and pace for cultural heritage research and discovery, is slowly but surely disappearing making it increasingly difficult for cultural heritage organisations to claim a position in a, "new digital order"28 — particular in an environment of every increasing financial pressures. (Prescott, 2012). In effect they are reduced to simple service providers with little or no stake in the outcomes.29

Within the vastly diverse and every changing nature of digital humanities projects how can organisations and projects collaborate with each other? How can they spend time and resource effectively in a highly fragmented world that ultimately works against effective collaboration? We believe that one answer is to change the emphasis from the inconsistent 'bursts' and instead focus on the underlying structures that could support more consistent innovation. By establishing the foundational structures that providers, aggregators and users of cultural data all have a common interest in maintaining, a more consistent approach to progressing in the digital humanities may be achieved. In such an environment projects are able to build tools and components that can be both diverse and innovative but that contribute to the analysis and management of a growing body of harmonised knowledge capable of supporting computer based reasoning.

The challenge is not about finding the right approach and methodology (these aspects being understood back in the 1990's) but rather how the ingrained practices of the last 20 years, determined mostly by technologists, can be reversed and a more collaborative, cross disciplinary and knowledge led approach can be achieved. This is a collaboration based not simply on university department collaboration but a far wider association of people and groups who provide an equally important role in establishing a healthy humanities ecosystem.

The CRM SIG has already started elaborating and experimenting with key elements for a new reference model of collaborative data provision and aggregation, in line with the requirements indicated above. Work on this new structure has already commenced in projects like CultureBrokers, a project in Sweden starting to develop some of the essential components described above. We call on other prospective aggregators, existing service providers and end users to pool resources and contribute to the development of this new and sustainable approach. Without such a collaboration the community risks never breaking out of a cycle based on flawed assumptions and restrictive ideas, and therefore never creating the foundational components necessary to take digital humanities to a higher intellectual, and practical, level.

Notes

1 Clough, G. Wayne, Secretary of the Smithsonian institute citing Robert Janes (Janes, 2009) in Best of Both Worlds: Museums, Libraries, and Archives in the Digital Age (Kindle Locations 550-551), (2013).

2 Synergy Reference Model of Data Provision and Aggregation. A working draft is available here.

3 Database engine for triple and quad statements in the model of the Resource Description Framework.

4 Solr™ is the fast open source search platform from the Apache Lucene™ project (http://lucene.apache.org/solr/).

5 A database using graph structures, i.e., every element contains a direct pointer to its adjacent elements.

6 The CIDOC CRM is largely agnostic about database technology, relying on a logical knowledge representation structure.

7 By "Digital Humanities" we mean not only philological applications but any support of cultural-historical research using computer science.

8 For the recent use of the term "cultural heritage fruition", see, e.g., "cultural assets protection, valorisation and fruition" in Cultural Heritage Space Identification System, Best Practices for the Fruition and Promotion of Cultural Heritage or Promote cultural fruition.

9 For example, the failed umbrella digital rights management model of MESL.

10 Paul Walk, former Deputy Director, UKOLN — transcribed from the conference video cast.

11 Panel included: Rachel Bruce, JISC; Maura Marx, The Digital Public Library of America; Alister Dunning, Europeana; Neil Wilson, British Library; Paul Walk, UKOLN; and David Baker, Resource Discovery Task Force.

12 Garbage in, garbage out (GIGO) in the field of computer science or information and communications technology refers to the fact that computers, since they operate by logical processes, will unquestioningly process unintended, even nonsensical, input data ("garbage in") and produce undesired, often nonsensical, output ("garbage out"). (Wikipedia)

13 Europeana, a European data aggregation project with a digital portal.

14 Only recently Europeana developed the still experimental EDM model, which adopted the event concept of the CIDOC CRM. Dublin Core application profiles implemented in RDF make use of some very general superproperties, such as dc:relation, dc:date, dc:description, dc:coverage. XML, JSON, Relational and Object-Relational data formats cannot represent superproperties.

15 In terms of RDF/OWL, one would speak of "superproperties", which are known to the schema and the database engine, but need not appear explicitly in the data. (Calvanese, Giacomo, and Lenzerini, 1998) use the terms, "relation subsumption" and "query containment".

16 A historiographic concern in respect of the tension between post-modern approaches and uncovering and exposing supposedly power relations across different political-economic phases. For example, (Jameson, 1991).

17 An approach associated with writers such W.G. Sebald, for example, see (Sebald, 2002).

18 The German Digital Library envisaged about 30,000 potential providers in Germany.

19 Hardly any tool supports sources as different as RDBMS, XML dialects, RDF, MS Excel, and tables in text formats.

20 See, for instance, the migration of Europeana from ESE to EDM.

21 See delving / x3ml for the X3ML mapping format development.

22 For example, the use of XSLT.

23 The reference model has been named 'Synergy'. A working draft is available here.

24 Formerly, Humanities Computing.

25 CLAROS, a CIDOC CRM-based aggregation of classical datasets from major collections across Europe.

26 ResearchSpace, TA project, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, to create an interactive research environment based on CIDOC CRM data harmonisation.

27 Culturebroker, a project mainly funded by a consortium led by the Swedish Arts Council implementing data provisioning using the new reference model for Swedish institutions.

28 Something different to simple information publication and the use of popular social networking facilities.

29 See The Two Art Histories, Haxthausen (2003) and The Museum Time Machine, Lumley (Ed.) (1988) for further evidence.

References

[1] Bayardo, R., et al. (1997) "InfoSleuth: Agent-Based Semantic Integration of Information in Open and Dynamic Environments", in ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, pp. 195-206.

[2] Bearman, D. (1995) "Standards for Networked Cultural Heritage". Archives and Museum Informatics, 9 (3), 279-307.

[3] Calvanese, D., Giacomo, G., Lenzerini, M., et al. (1998) "Description Logic Framework for Information Integration", in 6th International Conference on the Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning (KR'98), pp. 2-13.

[4] Calvanese, D., Giacomo, G. & Lenzerini, M. (1998) "On the decidability of query containment under constraints", in Principles of Database Systems, pp. 149-158.

[5] Consultative Committee for Space data Systems. (2009) "Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System" (OAIS).

[6] Crofts, N. et al. (eds.) (2011) "Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model".

[7] Delouis, D. (1993) "TOlOsystixnes France", in International Cultural Heritage Informatics.

[8] Doerr, M. (2003) "The CIDOC conceptual reference module: an ontological approach to semantic interoperability of metadata". AI Magazine, 24 (3), 75.

[9] Doerr, M. & Crofts, N. (1998) "Electronic espernato—The Role of the oo CIDOC Reference Model". Citeseer.

[10] Gruber, T. R. (1993) "Toward Principles for the Design of Ontologies Used for Knowledge Sharing". International Journal Human-Computer Studies, (43), 907-928.

[11] Greenhill, E. H. (1992) Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. Routledge.

[12] Haxthausen, Charles W. (2003) The Two Art Histories: The Museum and the University. Williamstown, Mass: Yale University Press.

[13] ICZN (1999) International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. 4th edition. The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature.

[14] Jameson, F. (1991) Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press.

[15] Janes, Robert R. (2009) Museums in a Troubled World: Renewal, Irrelevance or Collapse? London: Routledge, pp. 13.

[16] JISC (2013) "JISC Discovery Summit 2013".

[17] Lu, J. et al. (1996) "Hybrid Knowledge Bases". IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 8 (5), pp. 773-785.

[18] Lumley, Robert. (1988) The Museum Time Machine. Routledge.

[19] McCarty, W. (2011) "Beyond Chronology and Profession", in Hidden Histories Symposium. 17 September 2011, University College London.

[20] McGann, J. (2010) "Sustainability: The Elephant in the Room", from a Mellon Foundation Conference at the University of Virginia.

[21] Prescott, A. (2012) "An Electric Current of the Imagination." Digital Humanities: Works in Progress.

[22] Renn, J. (2006) "Towards a Web of Culture and Science". Information Services and Use 26 (2), pp. 73-79.

[23] Sebald, W. G. (2002) The Rings of Saturn. London: Vintage.

[24] Stewart, S. (1993) "On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection". Duke University Press.

[25] Tzompanaki, K., et al. (2013) "Reasoning based on property propagation on CIDOC-CRM and CRMdig based repositories", in Online Proceedings for Scientific Workshops.

[26] Tzompanaki, K. & Doerr, M. (2012) "Fundamental Categories and Relationships for intuitive querying CIDOC-CRM based repositories".

[27] Unsworth, J. (2002) "What is Humanities Computing and What is not?".

[28] Wiederhold, G. (1992) "Mediators in the Architecture of Future Information Systems". IEEE Computer.

About the Authors

|

Dominic Oldman is currently the Deputy Head of the British Museum's Information Systems department and specialises in systems integration, knowledge representation and Semantic Web/Linked Open Data technologies. He is a member of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model Special Interest Group (CRM SIG) and chairs the Bloomsbury Digital Humanities Group. He is also the Principal Investigator of ResearchSpace, a project funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation using CIDOC CRM to provide an on-line collaboration research environment. A law graduate he also holds a post graduate degree in Digital Humanities from King's College, London.

|

|

Martin Doerr is a Research Director at the Information Systems Laboratory and head of the Centre for Cultural Informatics of the Institute of Computer Science, FORTH. Dr. Doerr has been leading the development of systems for knowledge representation and terminology, metadata and content management. He has been leading or participating in a series of national and international projects for cultural information systems. His long-standing interdisciplinary work and collaboration with the International Council of Museums on modeling cultural-historical information has resulted besides others in an ISO Standard, ISO21127:2006, a core ontology for the purpose of schema integration across institutions. He is chair of the CRM SIG.

|

|

Gerald de Jong has a background in combinatorics and computer science from the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. He has a more than a decade of freelance experience in the Netherlands, both coding and training, including being part of the original Europeana technical team. He has a passion for finding simplicity in otherwise complex things, and with multi-agent and darwinistic approaches to solving gnarly problems. He co-founded Delving BV in 2010 to focus on the bigger information challenges in the domain of cultural heritage. He is a member of the CRM SIG.

|

|

Barry Norton is Development Manager of ResearchSpace, a project developing tools for the cultural heritage sector using Linked Data. He has worked on data-centric applications development since the mid 90's and holds a PhD on Semantic Web and software architecture topics from the University of Sheffield. Before working at the British Museum he worked as a consultant Solutions Architect following a ten year academic career at universities in Sheffield, London (Queen Mary), Karlsruhe, Innsbruck and at the Open University.

|

|

Thomas Wikman is an experienced manager working on national and European ICT projects and museum collaborations since the mid 90's. He is the Project manager and Co-ordinator at the Swedish National Archives for the CultureCloud and the CultureBroker projects. CultureBroker is an implementation of the Data Provisioning Reference Model and the CIDOC CRM aggregating archival and museum data. He is a member of the CRM SIG.

|

|