Cyberwarfare between Ukraine and Russia

Foreword

The first quarter of 2022 is over, so we are here again to share insights into the threat landscape and what we’ve seen in the wild. Under normal circumstances, I would probably highlight mobile spyware related to the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, yet another critical Java vulnerability (Spring4Shell), or perhaps how long it took malware authors to get back from their Winter holidays to their regular operations. Unfortunately, however, all of this was overshadowed by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Similar to what’s happening in Ukraine, the warfare co-occurring in cyberspace is also very intensive, with a wide range of offensive arsenal in use. To name a few, we witnessed multiple Russia-attributed APT groups attacking Ukraine (using a series of wiping malware and ransomware, a massive uptick of Gamaredon APT toolkit activity, and satellite internet connections were disrupted). In addition, hacktivism, DDoS attacks on government sites, or data leaks are ongoing daily on all sides of the conflict. Furthermore, some of the malware authors and operators were directly affected by the war, such as the alleged death of the Raccoon Stealer leading developer, which resulted in (at least temporary) discontinuation of this particular threat. Additionally, some malware gangs have chosen the sides in this conflict and have started threatening the others. One such example is the Conti gang that promised ransomware retaliation for cyberattacks against Russia. You can find more details about this story in this report.

With all that said, it is hardly surprising to say that we’ve seen a significant increase of attacks of particular malware types in countries involved in this conflict in Q1/2022; for example, +50% of RAT attacks were blocked in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus, +30% for botnets, and +20% for info stealers. To help the victims of these attacks, we developed and released multiple free ransomware decryption tools, including one for the HermeticRansom that we discovered in Ukraine just a few hours before the invasion started.

Out of the other malware-related Q1/2022 news: the groups behind Emotet and Trickbot appeared to be working closely together, resurrecting Trickbot infected computers by moving them under Emotet control and deprecating Trickbot afterward. Furthermore, this report describes massive info-stealing campaigns in Latin America, large adware campaigns in Japan, and technical support scams spreading in the US and Canada. Finally, again, the Lapsus$ hacking group emerged with breaches in big tech companies, including Microsoft, Nvidia, and Samsung, but hopefully also disappeared after multiple arrests of its members in March.

Last but not least, we’ve published our discovery of the latest Parrot Traffic Direction System (TDS) campaign that has emerged in recent months and is reaching users from around the world. This TDS has infected various web servers hosting more than 16,500 websites.

Stay safe and enjoy reading this report.

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Methodology

This report is structured into two main sections – Desktop-related threats, informing about our intelligence on attacks targeting Windows, Linux, and macOS, and Mobile-related threats, where we advise about Android and iOS attacks.

Furthermore, we use the term risk ratio in this report to describe the severity of particular threats, calculated as a monthly average of “Number of attacked users / Number of active users in a given country.” Unless stated otherwise, calculated risks are only available for countries with more than 10,000 active users per month.

Desktop-Related Threats

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)

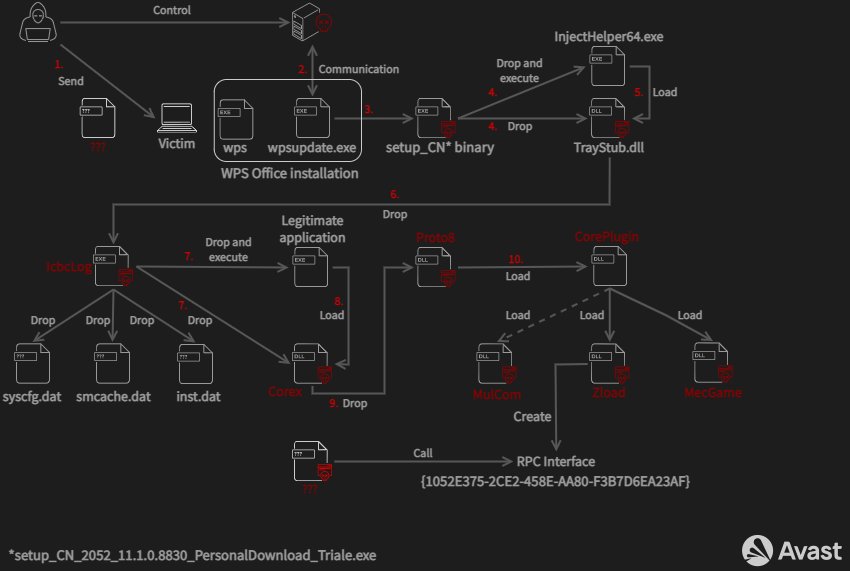

In March, we wrote about an APT campaign targeting betting companies in Taiwan, the Philippines, and Hong Kong that we called Operation Dragon Castling. The attacker, a Chinese-speaking group, leveraged two different ways to gain a foothold in the targeted devices – an infected installer sent in a phishing email and a newly identified vulnerability in the WPS Office updater (CVE-2022-24934). After successful infection, the malware used a diverse set of plugins to achieve privilege escalation, persistence, keylogging, and backdoor access.

Furthermore, on February 23rd, a day before Russia started its invasion of Ukraine, ESET tweeted that they discovered a new data wiper called HermeticWiper. The attacker’s motivation was to destroy and maximize damage to the infected system. It’s not just disrupting the MBR but also destroying a filesystem and individual files. Shortly after that, we at Avast discovered a related piece of ransomware that we called HermeticRansom. You can find more on this topic in the Ransomware section below. These attacks are believed to have been carried out by Russian APT groups.

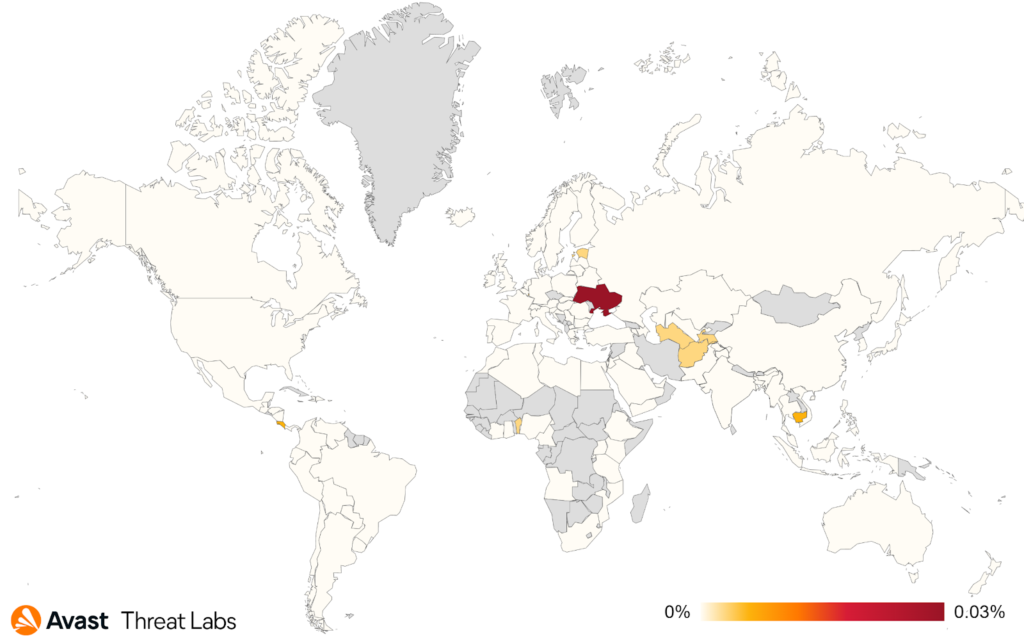

Continuing this subject, Gamaredon is known as the most active Russia-backed APT group targeting Ukraine. We see the standard high level of activity of this APT group in Ukraine which accelerated rapidly since the beginning of the Russian invasion at the end of February when the number of their attacks grew several times over.

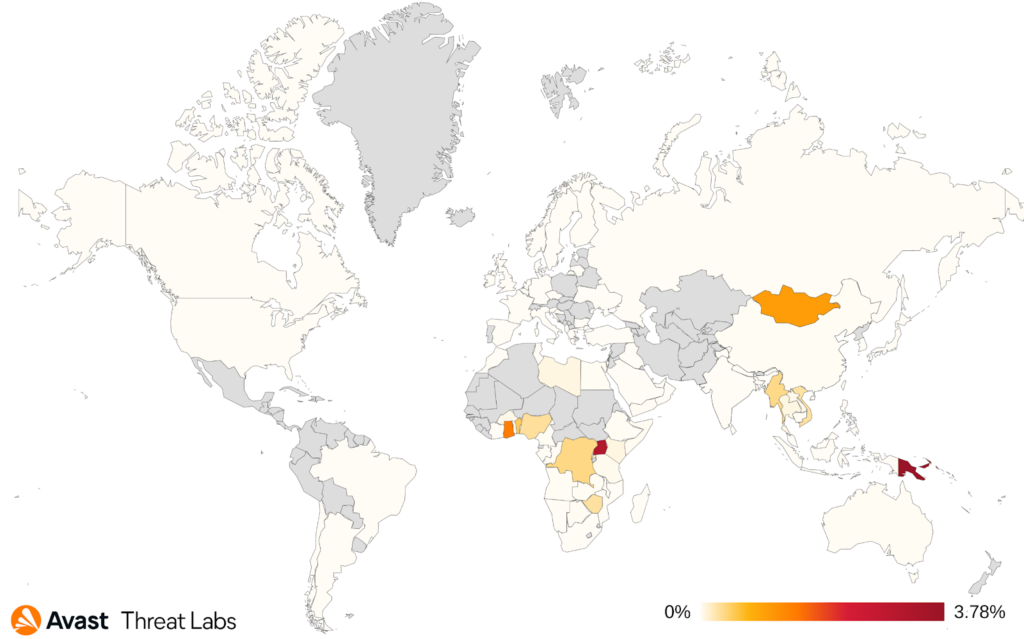

We also noticed an increase in Korplug activity which expanded its focus from the more usual south Asian countries such as Myanmar, Vietnam, or Thailand to Papua New Guinea and Africa. The most affected African countries are Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria. As Korplug is commonly attributed to Chinese APT groups, this new expansion aligns with their long-term interest in countries involved in China’s Belt and Road initiative.

Luigino Camastra, Malware Researcher

Igor Morgenstern, Malware Researcher

Jan Holman, Malware Researcher

Adware

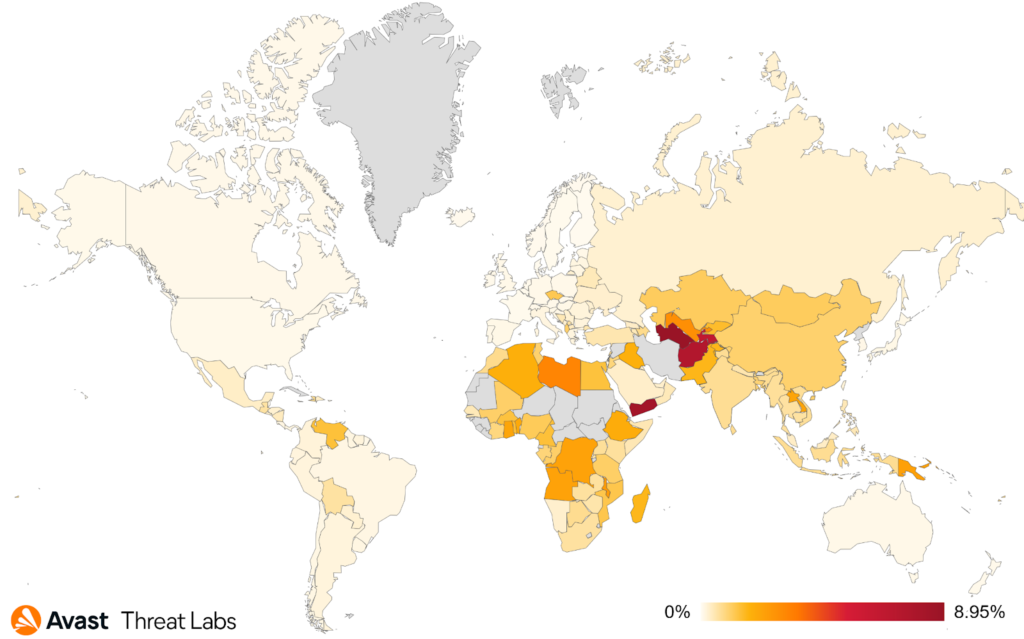

Desktop adware has become more aggressive in Q4/21, and a similar trend persists in Q1/22, as the graph below illustrates:

On the other hand, there are some interesting phenomena in Q1/22. Firstly, Japan’s proportion of adware activity has increased significantly in February and March; see the graph below. There is also an interesting correlation with Emotet hitting Japanese inboxes in the same period.

On the contrary, the situation in Ukraine led to a decrease in the adware activity in March; see the graph below showing the adware activity in Ukraine in Q1/22.

Finally, another interesting observation concerns adware activity in major European countries such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The graph below shows increased activity in these countries in March, deviating from the trend of Q1/22.

Concerning the top strains, most of 64% of adware was from various adware families. However, the first clearly identified family is RelevantKnowledge, although so far with a low prevalence (5%) but with a +97% increase compared to Q4/21. Other identified strains in percentage units are ICLoader, Neoreklami, DownloadAssistant, and Conduit.

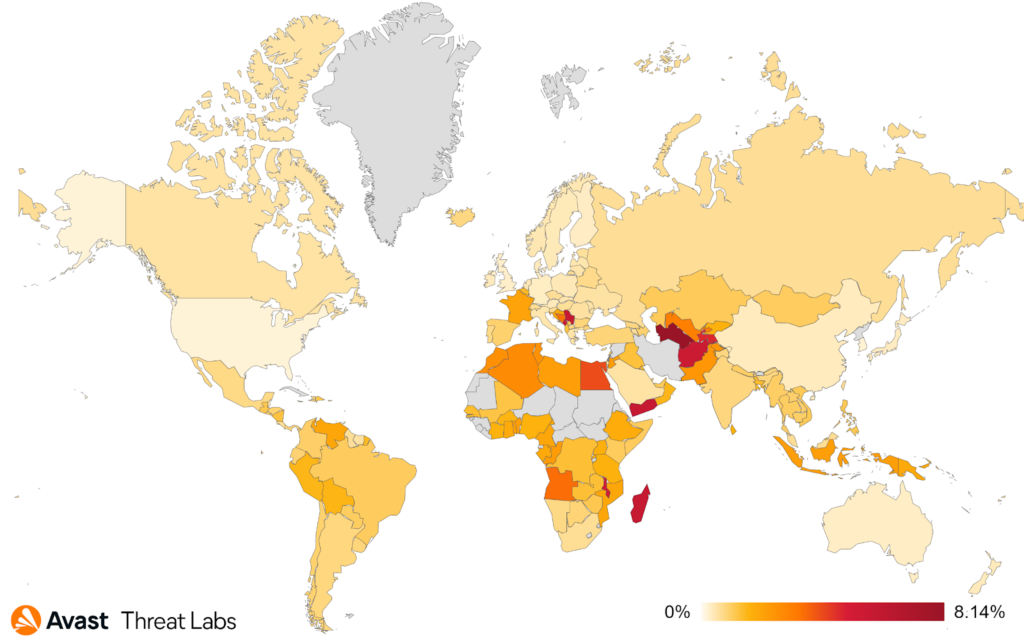

As mentioned above, the adware activity has a similar trend as in Q4/21. Therefore the risk ratios remained the same. The most affected regions are still Africa and Asia. About Q1/22 data, we monitored an increase of protected users in Japan (+209%) and France (+87%) compared with Q4/21. On the other hand, a decrease was observed in the Russian Federation (-51%) and Ukraine (-50%).

Adware risk ratio in Q1/22.

Martin Chlumecký, Malware Researcher

Bots

It seems that we are on a rollercoaster with Emotet and Trickbot. Last year, we went through Emotet takedown and its resurrection via Trickbot. This quarter, shutdowns of Trickbot’s infrastructure and Conti’s internal communication leaks indicate that Trickbot has finished its swan song. Its developers were supposedly moved to other Conti projects, possibly also with BazarLoader as Conti’s new product. Emotet also introduced a few changes – we’ve seen a much higher cadence of new, unique configurations. We’ve also seen a new configuration timestamp in the log “20220404”, interestingly seen on 24th March, instead of the one we’ve been accustomed to seeing (“20211114”).

There has been a new-ish trend coming with the advent of the war in Ukraine. Simple Javascript code has been used to create requests to (mostly) Russian web pages – ranging from media to businesses to banks. The code was accompanied by a text denouncing Russian aggression in Ukraine in multiple languages. The code has quickly spread around the internet into different variations, such as a variant of open-sourced game 2048. Unfortunately, we’ve started to see webpages that incorporated that code without even declaring it so it could even happen that your computer would participate in those actions while you were checking the weather on the internet. While these could remind us of Anonymous DDoS operations and LOIC (open-source stress tool Low Orbit Ion Cannon), these pages were much more accessible to the public using their browser only with (mostly) predetermined lists of targets. Nearing the end of March, we saw a significant decline in their popularity, both in terms of prevalence and the appearance of new variants.

The rest of the landscape does not bring many surprises. We’ve seen a significant risk increase in Russia (~30%) and Ukraine (~15%); those shouldn’t be much of a surprise, though, for the latter, it mostly does not project much into the number of affected clients.

In terms of numbers, the most prevalent strain was Emotet which doubled its market share since last quarter. Since the previous quarter, most of the other top strains slightly declined their prevalence. The most common strains we are seeing are:

- Emotet

- Amadey

- Phorpiex

- MyloBot

- Nitol

- MyKings

- Dorkbot

- Tofsee

- Qakbot

Adolf Středa, Malware Researcher

Coinminers

Coincidently, as the cryptocurrency prices are somewhat stable these days, the same goes for the malicious coinmining activity in our user base.

In comparison with the previous quarter, crypto-mining threat actors increased their focus on Taiwan (+69%), Chile (+63%), Thailand (+61%), Malawi (+58%), and France (+58%). This is mainly caused by the continuous and increasing trend of using various web miners executing javascript code in the victim’s browser. On the other hand, the risk of getting infected significantly dropped in Denmark (-56%) and Finland (-50%).

The most common coinminers in Q1/22 were:

- XMRig

- NeoScrypt

- CoinBitMiner

- CoinHelper

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

Information Stealers

The activities of Information Stealers haven’t significantly changed in Q1/22 compared to Q4/21. FormBook, AgentTesla, and RedLine remain the most prevalent stealers; in combination, they are accountable for 50% of the hits within the category.

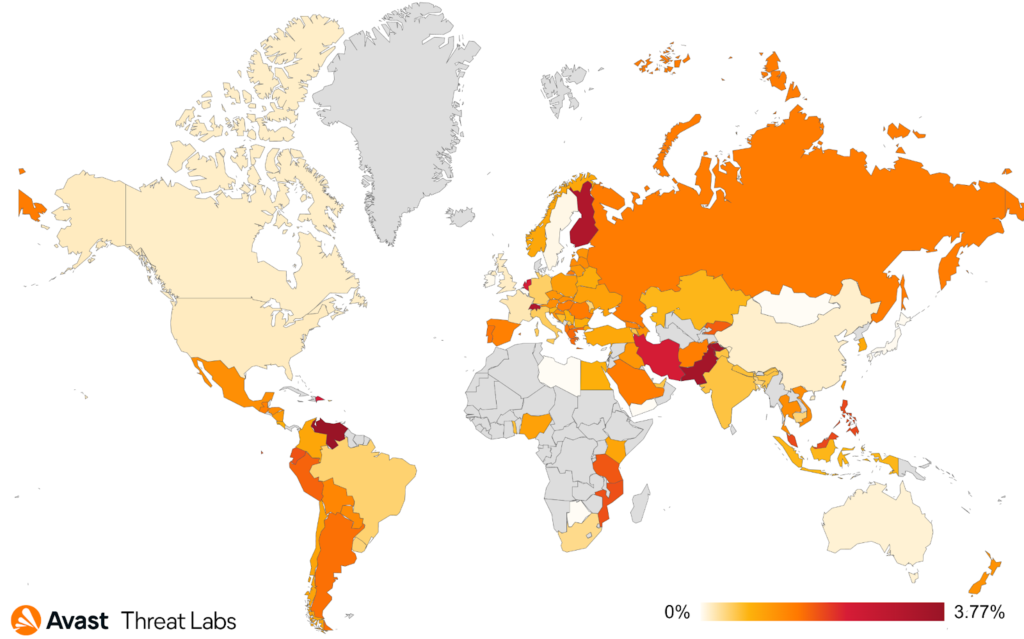

We noticed the regional distribution has completely shifted compared to the previous quarter. In Q4/21, Singapore, Yemen, Turkey, and Serbia were the countries most affected by information stealers; in Q1/22, Russia, Brazil, and Argentina rose to the top tier after the increases in risk ratio by 27% (RU), 21% (BR), and 23% (AR) compared to the previous quarter.

Not only a popular destination for information stealers, Latin America also houses many regional-specific stealers capable of compromising victims’ banking accounts. As the underground hacking culture continues to develop in Brazil, these threat groups target their fellow citizens for financial purposes. In Brazil, Ousaban and Chaes pose the most significant threats with more than 100k and 70k hits. In Mexico in Q1/22, we observed more than 34k hits from Casbaneiro. A typical pattern shared between these groups is the multiple-stage delivery chain utilizing scripting languages to download and deploy the next stage’s payload while employing DLL sideloading techniques to execute the final stage.

Furthermore, Raccoon Stealer, an information stealer with Russian origins, significantly decreased in activity since March. Further investigation uncovered messages on Russian underground forums advising that the Raccoon group is not working anymore. A few days after the messages were posted, a Raccoon representative said one of their members died in the Ukrainian War – they have paused operations and plan to return in a few months with a new product.

Next, a macOS malware dubbed DazzleSpy was found using watering hole attacks targeting Chinese pro-democracy sympathizers; it was primarily active in Asia. This backdoor can control macOS remotely, execute arbitrary commands, and download and upload files to attackers, thus enabling keychain stealing, key-logging, and potential screen capture.

Last but not least, more malware that natively runs on M1 Apple chips (and Intel hardware) has been found. The malware family, SysJoker, targets all desktop platforms (Linux, Windows, and macOS); the backdoor is controlled remotely and allows downloading other payloads and executing remote commands.

Anh Ho, Malware Researcher

Igor Morgenstern, Malware Researcher

Vladimir Martyanov, Malware Researcher

Vladimír Žalud, Malware Analyst

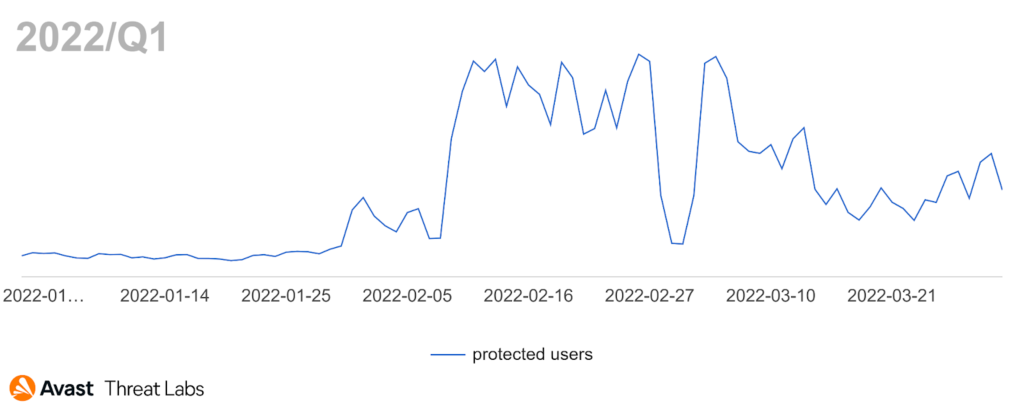

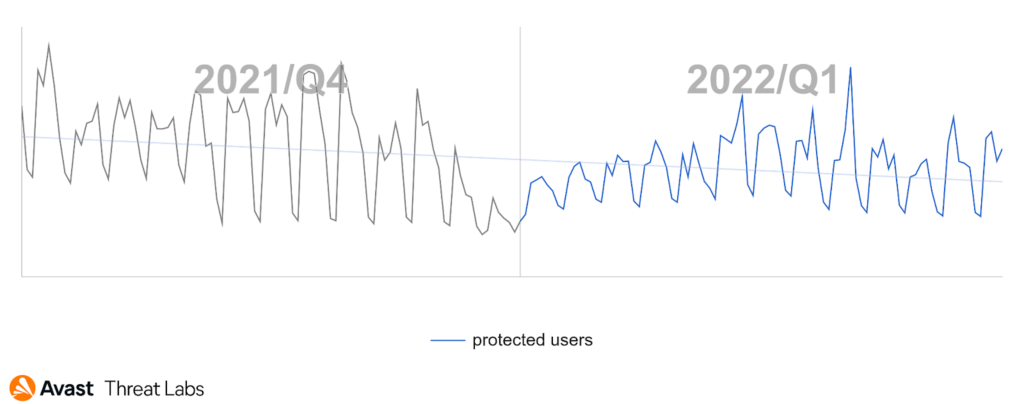

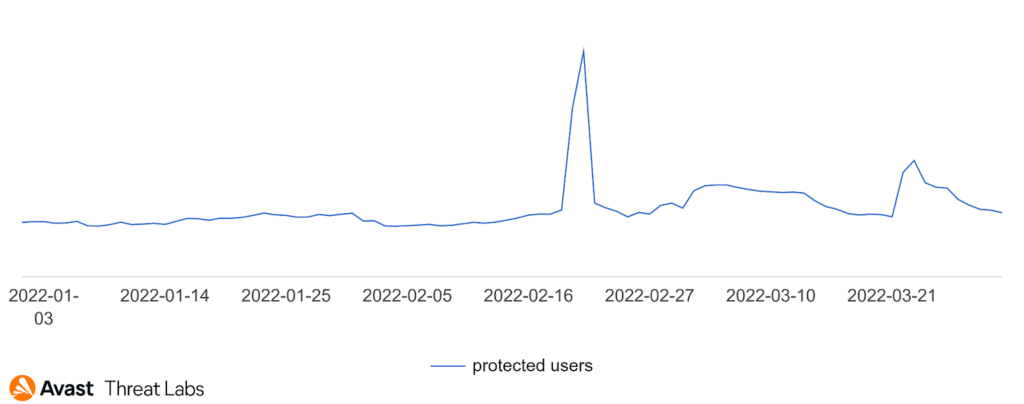

Ransomware

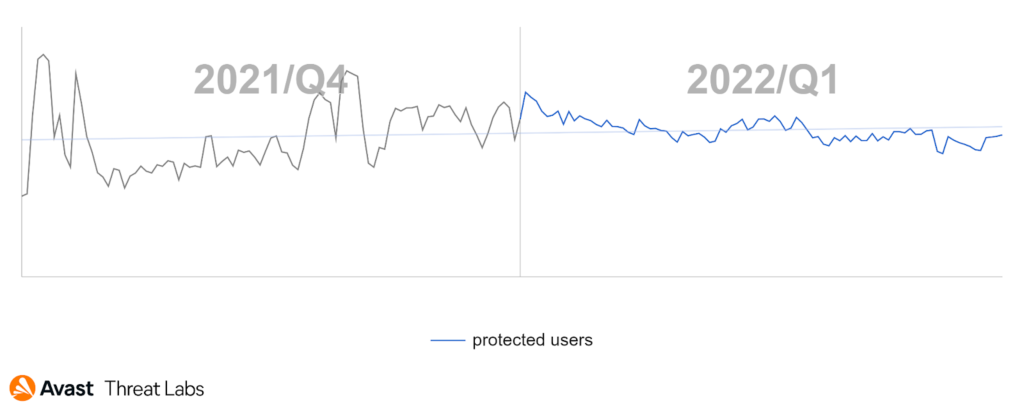

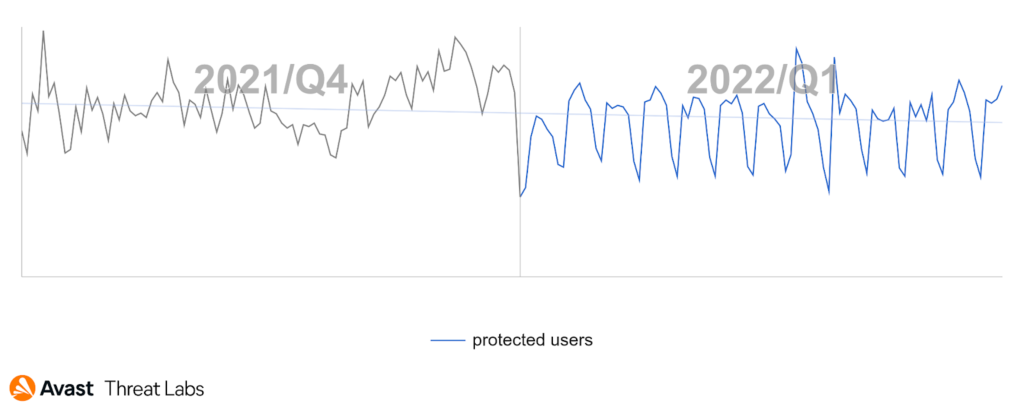

We’ve previously reported a decline in the total number of ransomware attacks in Q4/21. In Q1/22, this trend continued with a further slight decrease. As can be seen on the following graph, there was a drop at the beginning of 2022; the number of ransomware attacks has since stabilized.

We believe there are multiple reasons for these recent declines – such as the geopolitical situation (discussed shortly) and the continuation of the trend of ransomware gangs focusing more on targeted attacks on big targets (big game hunting) rather than on regular users via the spray and pray techniques. In other words, ransomware is still a significant threat, but the attackers have slightly changed their targets and tactics. As you will see in the rest of this section, the total numbers are lower, but there was a lot ongoing regarding ransomware in Q1.

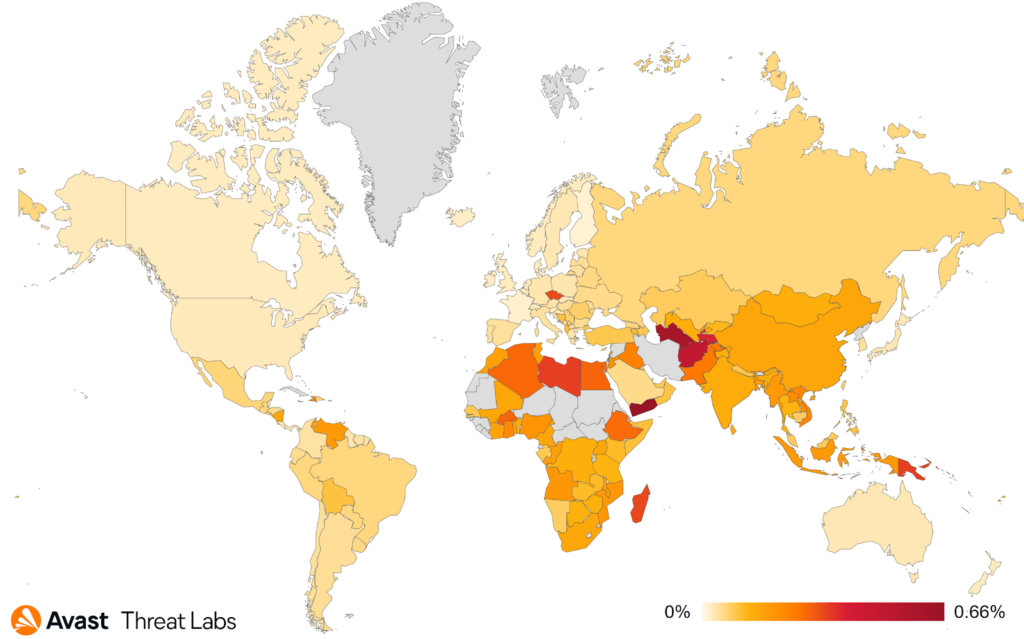

Based on our telemetry, the distribution of targeted countries is similar to Q4/21 with some Q/Q shifts, such as Mexico (+120% risk ratio), Japan (+37%), and India (+34%).

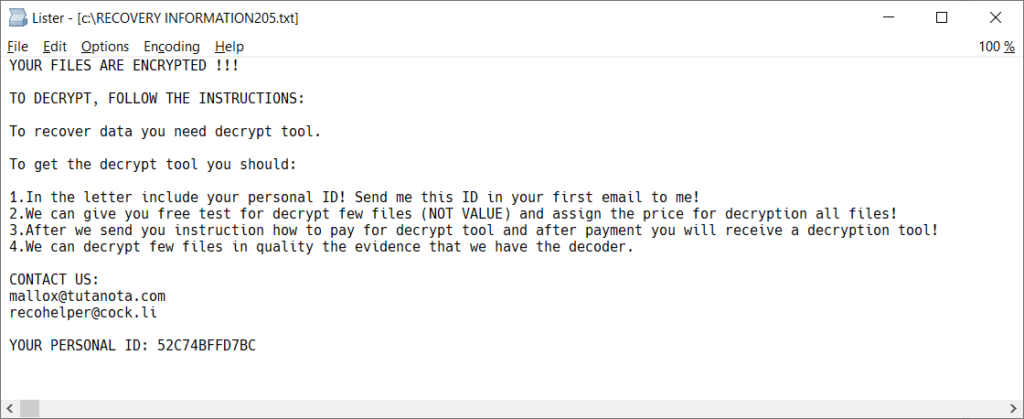

The most (un)popular ransomware strains – STOP and WannaCry – kept their position at the top. Operators of the STOP ransomware keep releasing new variants, and the same applies for the CrySiS ransomware. In both cases, the ransomware code hasn’t considerably evolved, so a new variant merely means a new extension of encrypted files, different contact e-mail and a different public RSA key.

The most prevalent ransomware strains in Q1/22:

- WannaCry

- STOP

- VirLock

- GlobeImposter

- Makop

Out of the groups primarily focused on targeted attacks, the most active ones based on our telemetry were LockBit, Conti, and Hive. The BlackCat (aka ALPHV) ransomware was also on the rise. The LockBit group boosted their presence and also their egos, as demonstrated by their claim that they will pay any FBI agent that reveals their location a bounty of $1M. Later, they expanded that offer to any person on the planet.

You may also recall Sodinokibi (aka REvil), which is regularly mentioned in our threat reports. There is always something interesting around this ransomware strain and its operators with ties to Russia. In our Q4/21 Threat Report we informed about the arrests of some of its operators by Russian authorities. Indeed, this resulted in Sodinokibi almost vanishing from the threat landscape in Q1/2022. However, the situation got messy at the very end of Q1/2022 and early in April as new Sodinokibi indicators started appearing, including the publishing of new leaks from ransomed companies and malware samples. It is not yet clear whether this is a comeback, an imposter operation, reused Sodinokibi sources or infrastructure, or even their combination by multiple groups. Our gut feeling is that Sodinokibi will be a topic in the Q2/22 Threat Report once again.

Russian ransomware affiliates are a never-ending story. E.g. we can mention an interesting public exposure of a criminal dubbed Wazawaka with ties to Babuk, DarkSide, and other ransomware gangs in February. In a series of drunk videos and tweets he revealed much more than his missing finger.

The Russian invasion and following war on Ukraine, the most terrible event in Q1/22, had its counterpart in cyber-space. Just one day before the invasion, several cyber attacks were detected. Shortly after the discovery of HermeticWiper malware by ESET, Avast also discovered ransomware attacking Ukrainian targets. We dubbed it HermeticRansom. Shortly after, a flaw in the ransomware was found by CrowdStrike analysts. We acted swiftly and released a free decryptor to help victims in Ukraine. Furthermore, the war impacted ransomware attacks, as some of the ransomware authors and affiliates are from Ukraine and likely have been unable to carry out their operations due to the war.

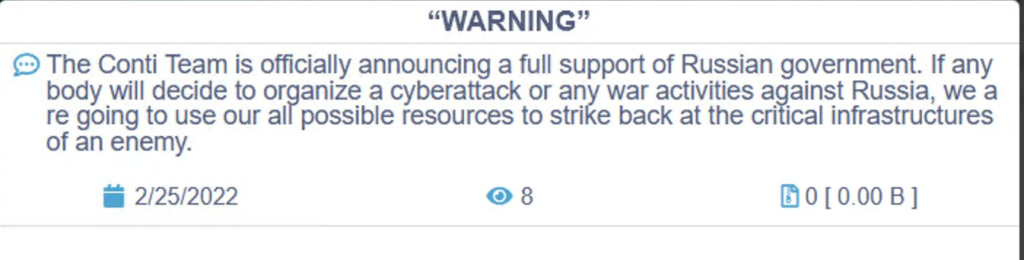

And the cyber-war went on, together with the real one. A day after the start of the invasion, the Conti ransomware gang claimed its allegiance and threatened anyone who was considering organizing a cyber-attack or war activities against Russia:

As a reaction, a Ukrainian researcher started publishing internal files of the Conti gang, including Jabber conversations and the source code of the Conti ransomware itself. However, no significant amount of encryption keys were leaked. Also, the sources that were published were older versions of the Conti ransomware, which no longer correspond to the layout of the encrypted files that are created by today’s version of the ransomware. The leaked files and internal communications provide valuable insight into this large cybercrime organization, and also temporarily slowed down their operations.

Among the other consequences of the Conti leak, the published source codes were soon used by the NB65 hacking group. This gang declared a karmic war on Russia and used one of the modified sources of the Conti ransomware to attack Russian targets.

Furthermore, in February, members of historically one of the most active (and successful) ransomware groups, Maze, announced a shut-down of their operation. They published master decryption keys for their ransomware strains Maze, Egregor, and Sekhmet; four archive files were published that contained:

- 19 private RSA-2048 keys for Egregor ransomware. Egregor uses a three-key encryption schema (Master RSA Key → Victim RSA Key → Per-file Key).

- 30 private RSA-2048 keys (plus 9 from old version) for Maze ransomware. Maze also uses a three-key encryption scheme.

- A single private RSA-2048 key for Sekhmet ransomware. Because this strain uses this RSA key to encrypt the per-file key, the RSA private key is likely campaign specific.

- A source code for the M0yv x86/x64 file infector, that was used by Maze operators in the past.

Next, an unpleasant turn of events happened after we released a decryptor for the TargetCompany ransomware in February. This immediately helped multiple ransomware victims; however, two weeks later, we discovered a new variant of TargetComany that started using the ”.avast” extension for encrypted files. Shortly after, the malware authors changed the encryption algorithm, so our free decryption tool does not decrypt the most recent variant.

On the bright side, we also analyzed multiple variants of the Prometheus ransomware and released a free decryptor. This one covers all decryptable variants of the ransomware strain, even the latest ones.

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Ladislav Zezula, Malware Researcher

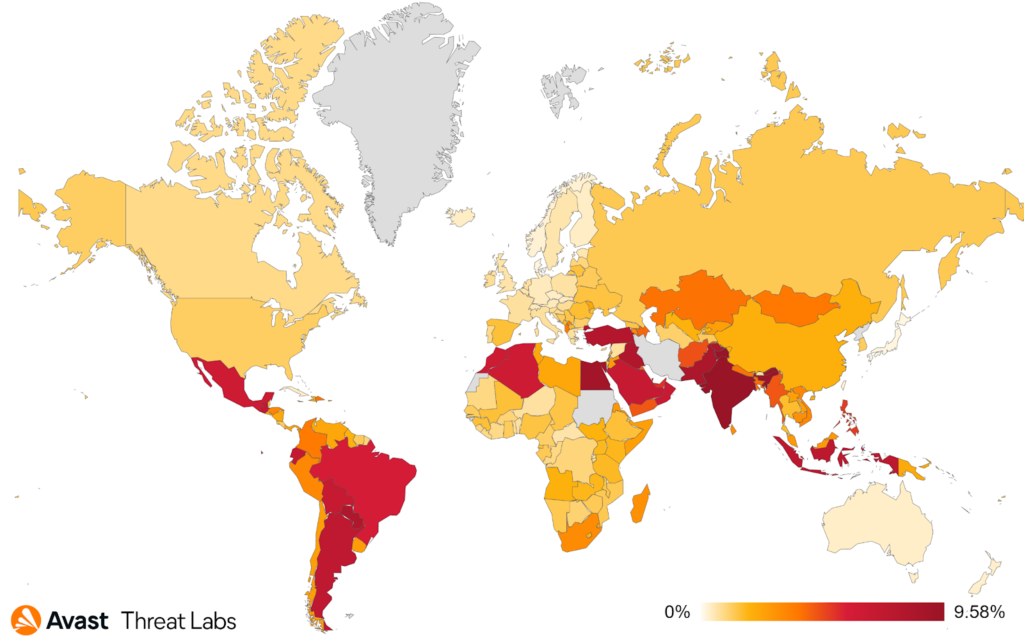

Remote Access Trojans (RATs)

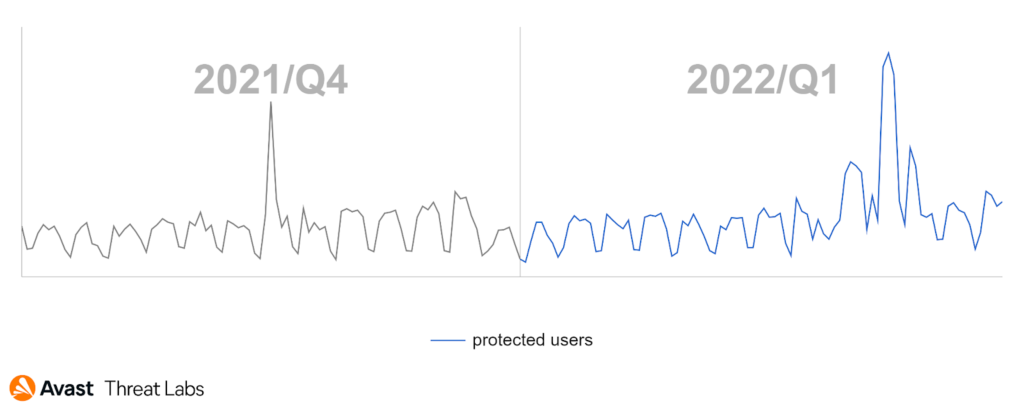

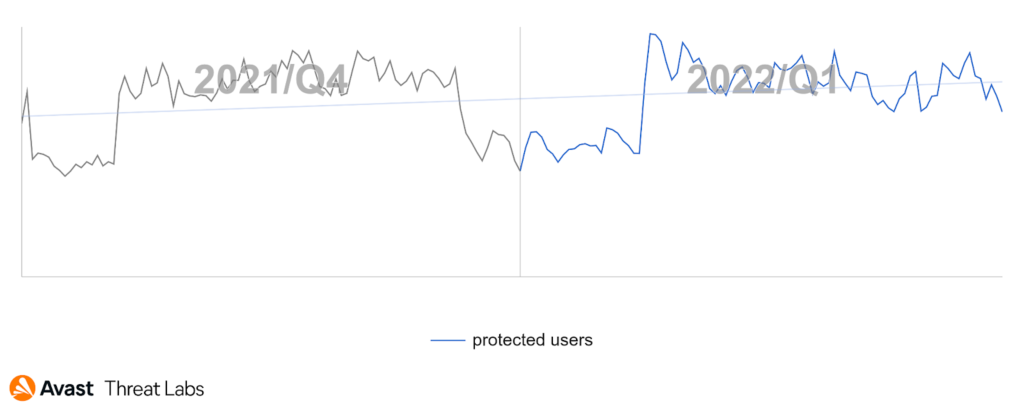

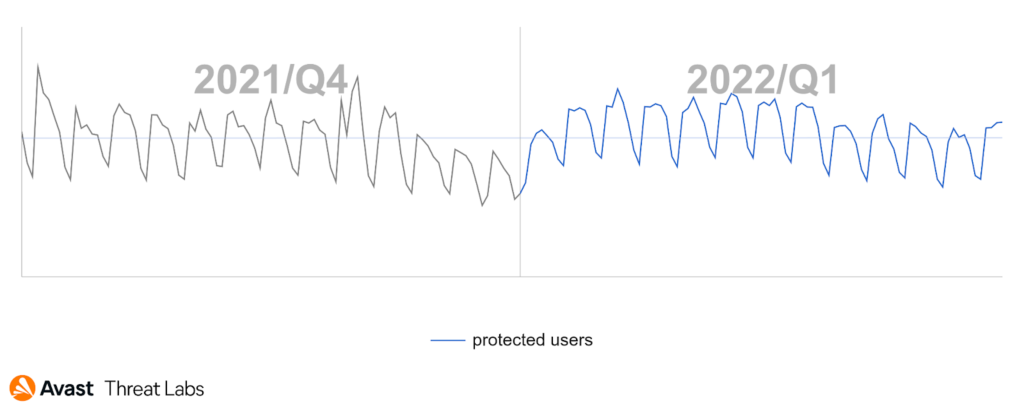

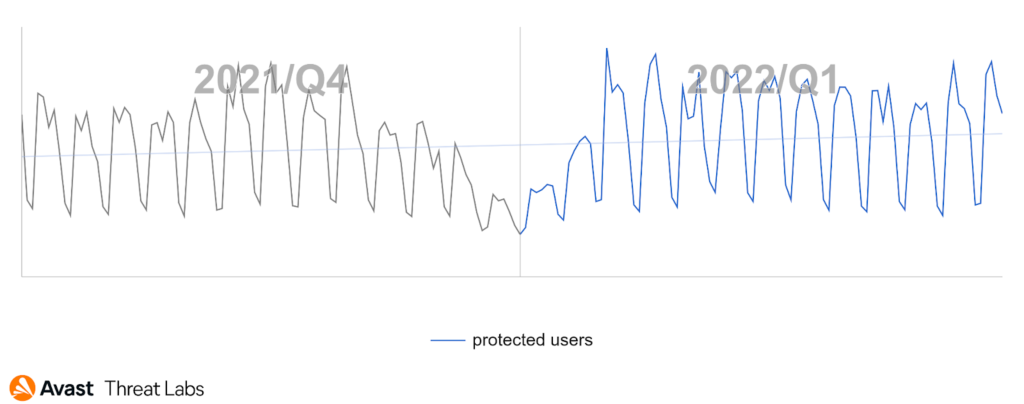

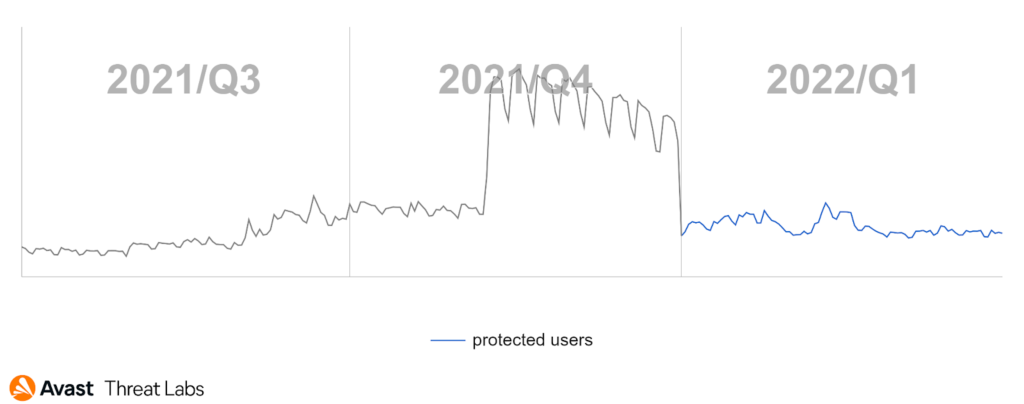

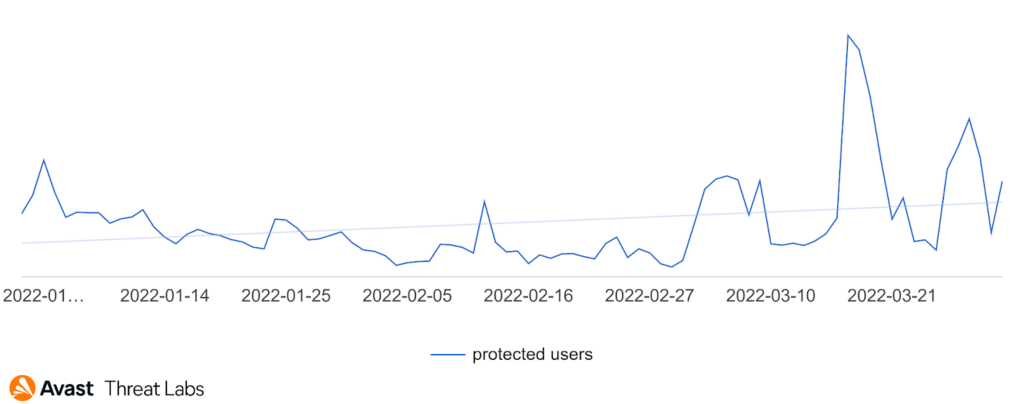

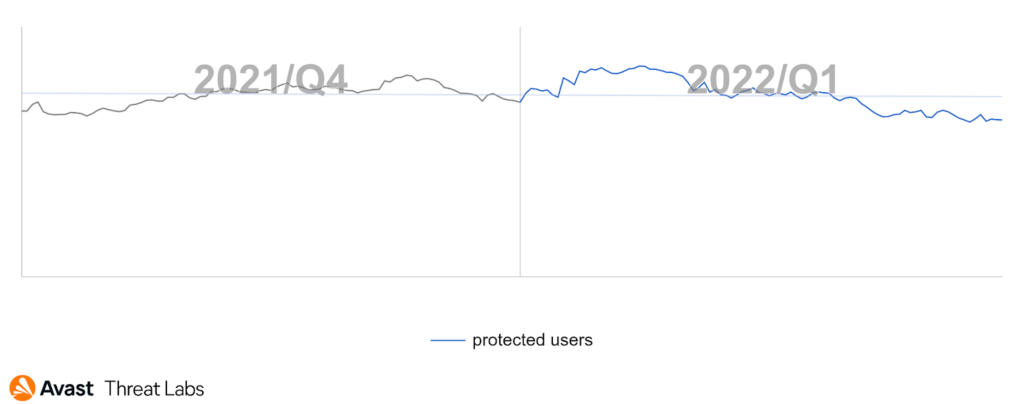

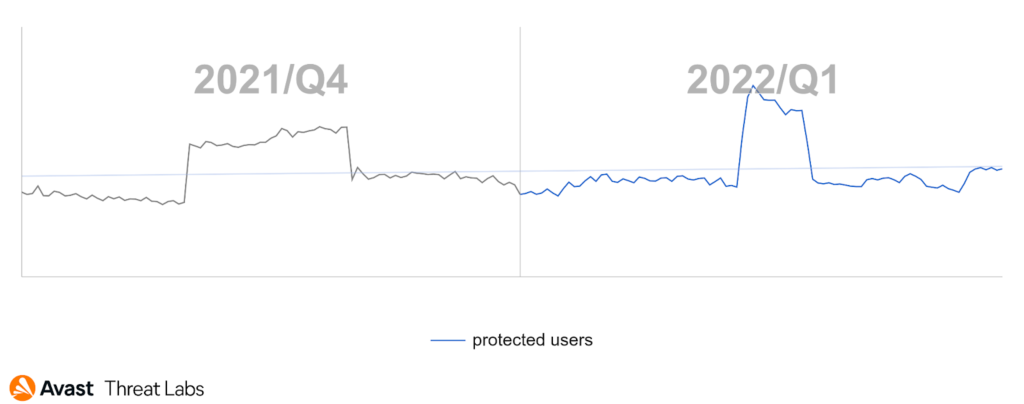

New year, new me RAT campaigns. As mentioned in the Q4/21 report, the RAT activity downward trend will be just temporary; the reality was a textbook example of this claim. Even malicious actors took holidays at the beginning of the new year and then returned to work.

In the graph below, we can see a Q4/21 vs. Q1/22 comparison of RAT activity:

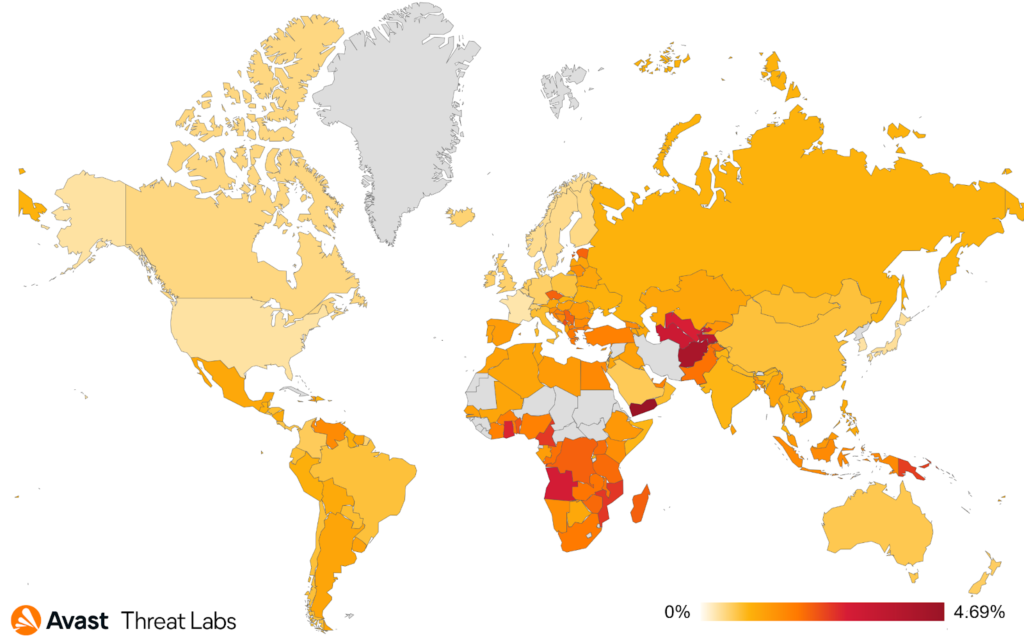

This quarter’s countries most affected were China, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Iraq, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Kazakhstan will be mentioned later on with the emergence of a new RAT. We also detected a high Q/Q increase in the risk ratio in countries involved in the ongoing war: Ukraine (+54%), Russia (+53%), and Belarus (+46%).

In this quarter, we spotted a new campaign distributing several RATs, reaching thousands of users, mainly in Italy (1,900), Romania (1,100), and Bulgaria (950). The campaign leverages a Crypter (a crypter is a specific tool used by malware authors for obfuscation and protection of the target payload), which we call Rattler, that ensures a distribution of arbitrary malware onto the victim’s PC. Currently, the crypter primarily distributes remote access trojans, focusing on Warzone, Remcos, and NetWire. Warzone’s main targeting campaigns also seemed to change during the past three months. In January and February, we received a considerable amount of detections from Russia and Ukraine. Still, this trend reversed in March, with decreased detections in these two countries and a significant increase in Spain, indicating a new malicious campaign.

Most prevalent RATs in Q1 were:

- njRAT

- Warzone

- Remcos

- AsyncRat

- NanoCore

- NetWire

- QuasarRAT

- PoisionIvy

- Adwind

- Orcus

Among malicious families with the highest increase in detections were Lilith, LuminosityLink, and Gh0stCringe. One of the reasons for the Gh0stCringe increase is a malicious campaign in which this RAT spread on poorly protected MySQL and Microsoft SQL database servers. We have also witnessed a change in the first two places of the most prevalent RATs. In Q4/21, the most pervasive was Warzone which declined this quarter by 23%. The njRat family, on the other hand, increased by 32%, and what was surprising, Adwind entered into the top 10.

Except for the usual malicious campaigns, this quarter was different. There were two significant causes for this. The first was a Lapsus$ hacking and leaking spree, and the other was the war with Ukraine.

The hacking group Lapsus$ targeted many prominent technology companies like Nvidia, Samsung, and Microsoft. For example, in the NVIDIA Lapsus$ case, this hacking group stole about 1TB of NVIDIA’s data and then commenced to leak it. The leaked data contained binary signing certificates, which were later used for signing malicious binaries. Among such signed malware was, for example, the Quasar RAT.

Then there was the conflict in Ukraine, which showed the power of information technology and the importance of cyber security – because the fight happens not only on the battlefield but also in cyberspace, with DDOS attacks, data-stealing, exploitation, cyber espionage, and other techniques. But except for these countries involved in the war, everyday people looking for information are easy targets of malicious campaigns. One such campaign involved sending email messages with attached office documents that allegedly contained important information about the war. Unfortunately, these documents were just a way to infect people with Remcos RAT with the help of Microsoft Word RCE vulnerability CVE-2017-11882, thanks to which the attacker could easily infect unpatched systems.

As always, not only old known RATs showed up. This quarter brought us a few new ones as well. The first addition to our RAT list was IceBot. This RAT seems to be a creation of the APT group FIN7; it contains all usual basic capabilities as other RATs like taking screenshots, remote code execution, file transfer, and detection of installed AV.

Another one is Hodur. This RAT is a variant of PlugX (also known as Korplug), associated with Chinese APT organizations. Hodur differed, using a different encoding, configuration capabilities, and C&C commands. This RAT allows attackers to log keystrokes, manipulate files, fingerprint the system and more.

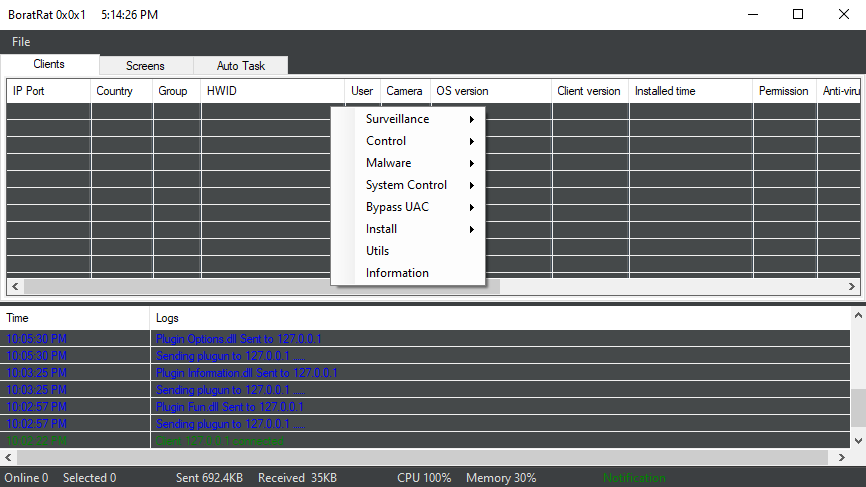

We mentioned that Kazakhstan is connected to a new RAT on this list. That RAT is called Borat RAT. The name is taken from the popular comedy film Borat where the main character Borat Sagdijev, performed by actor Sacha Baron Cohen, was presented as a Kazakh visiting the USA. Did you know that in reality the part of the film that should represent living in Kazakhstan village wasn’t even filmed there but in the Romanian village of Glod?

This RAT is a .NET binary and uses simple source-code obfuscation. The Borat RAT was initially discovered on hacking forums and contains many capabilities. Some features include triggering BSOD, anti-sandbox, anti-VM, password stealing, web-cam spying, file manipulation and more. As well as these baked-in features, it enables extensive module functionality. These modules are DLLs that are downloaded on demand, allowing the attackers to add multiple new capabilities. The list of currently available modules contains files “Ransomware.dll” used for encrypting files, “Discord.dll” for stealing Discord tokens, and many more.

Here you can see an example of the Borat RAT admin panel.

We also noticed that the volume of Python compiled and Go programming language ELF binaries for Linux increased this quarter. The threat actors used open source RAT projects (i.e. Bring Your Own Botnet or Ares) and legitimate services (e.g. Onion.pet, termbin.com or Discord) to compromise systems. We were also one of the first to protect users against Backdoorit and Caligula RATs; both of these malware families were written in Go and captured in the wild by our honeypots.

Samuel Sidor, Malware Researcher

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

David Àlvarez, Malware Researcher

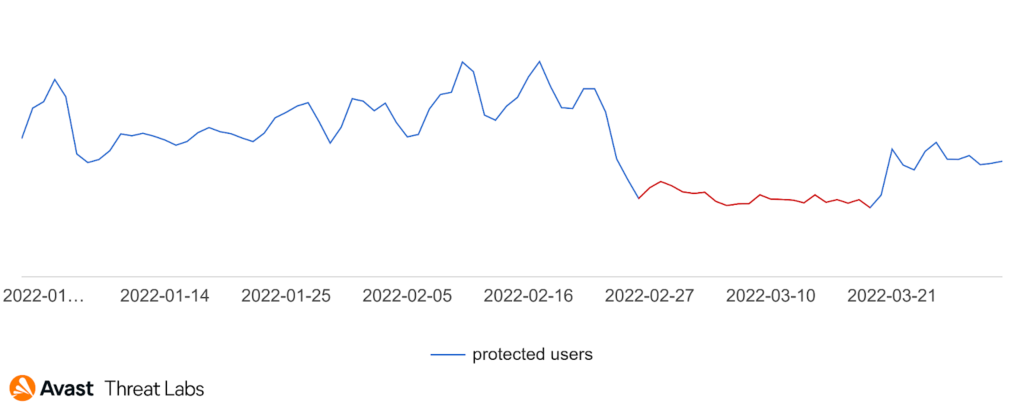

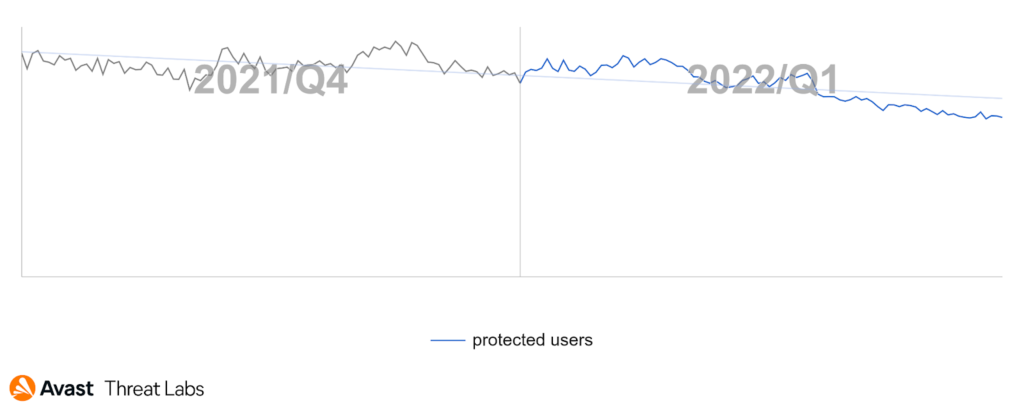

Rootkits

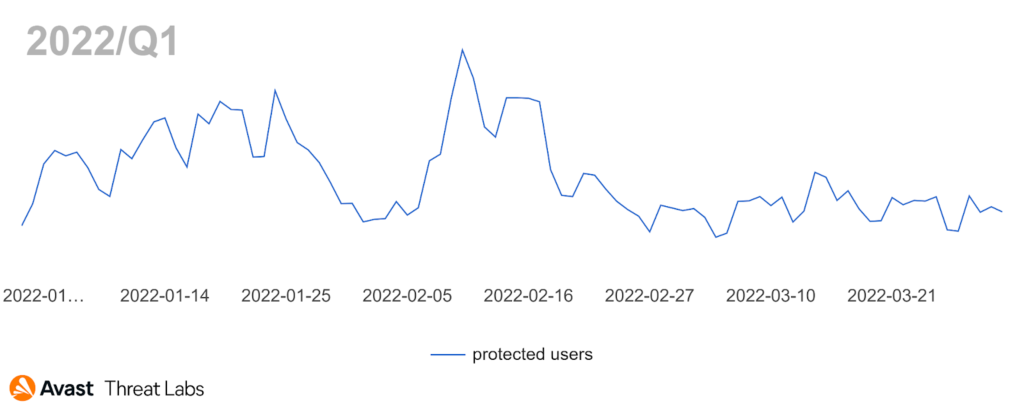

In Q1/22, rootkit activity was reduced compared to the previous quarter, returning to the long-term value, as illustrated in the chart below.

The close-up view of Q1/22 demonstrates that January and February have been more active than the March period.

We have monitored various rootkit strains in Q1/22. However, we have identified that approx. 37% of rootkit activity is r77-Rootkit (R77RK) developed by bytecode77 as an open-source project under the BSD license. The rootkit operates in Ring 3 compared to the usual rootkits that work in Ring 0. R77RK is a configurable tool hiding files, directories, scheduled tasks, processes, services, connections, etc. The tool is compatible with Windows 7 and Windows 10. The consequence is that R77RK was captured with several different types of malware as a supporting library for malware that needs to hide malicious activity.

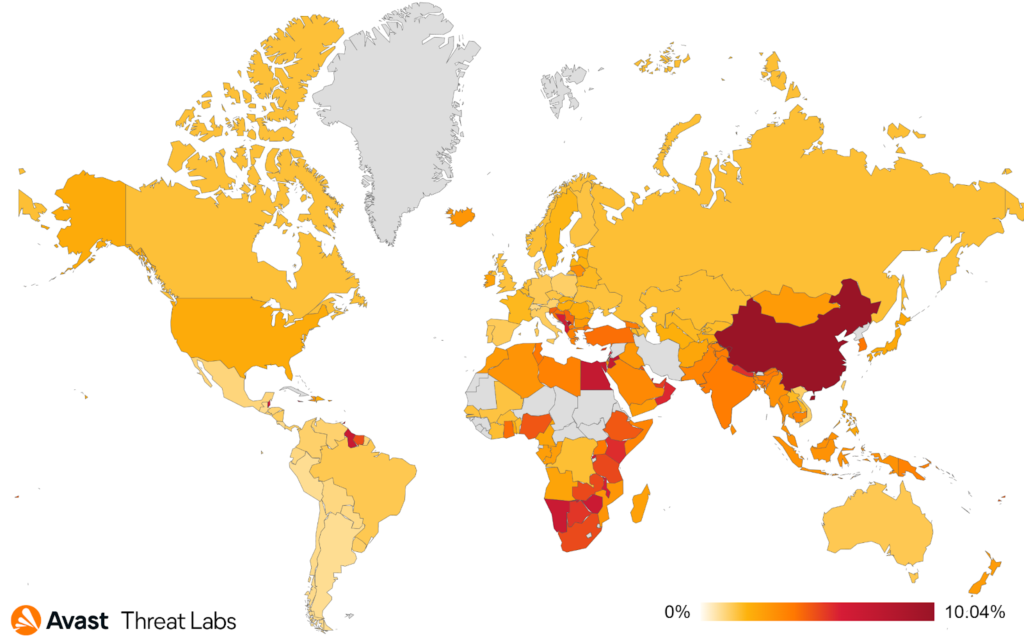

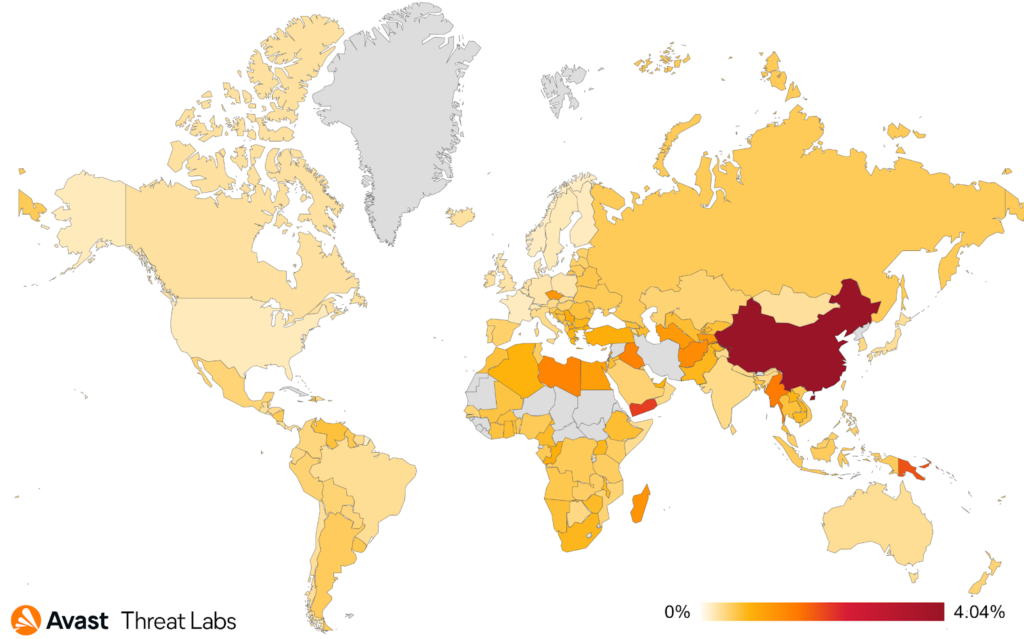

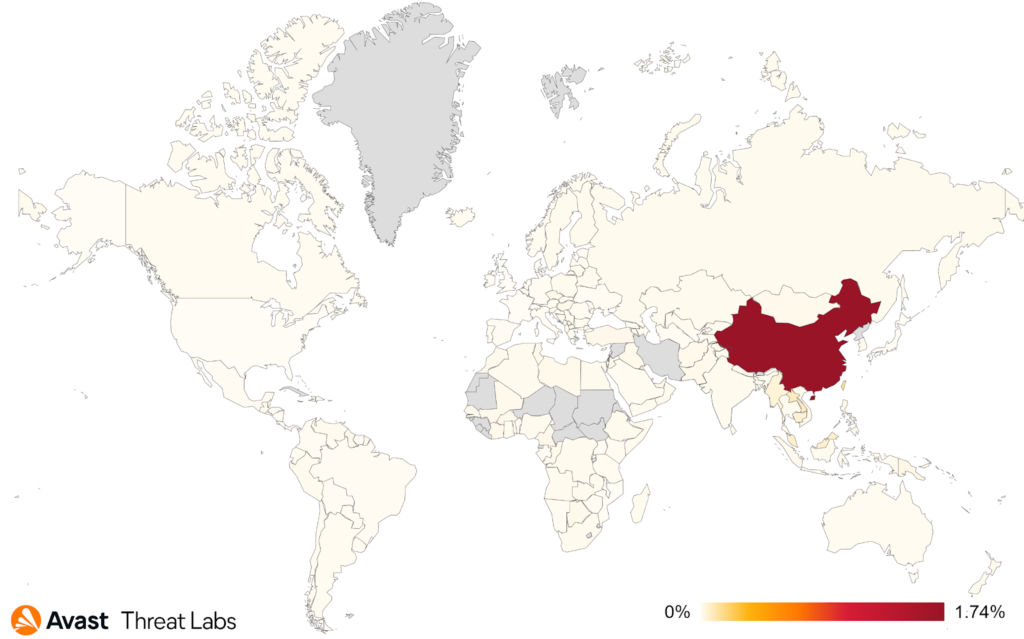

The graph below shows that China is still the most at-risk country in terms of protected users. Moreover, the risk in China has increased by about +58%, although total rootkit activity has been orders of magnitude lower compared to Q4/21. This phenomenon is caused by the absence of the Cerbu rootkit that was spread worldwide, so the main rootkit activity has moved back to China. Namely, the decrease in the rootkit activity has been observed in the countries as follows: Vietnam, Thailand, the Czech Republic, and Egypt.

In summary, the situation around the rootkit activity seems calmer compared to Q4/21, and China is still the most affected country in Q1/22. Noteworthy, the war in Ukraine has not increased the rootkit activity. Numerous malware authors have started using open-source solutions of rootkits, although these are very well detectable.

Martin Chlumecký, Malware Researcher

Technical support scams

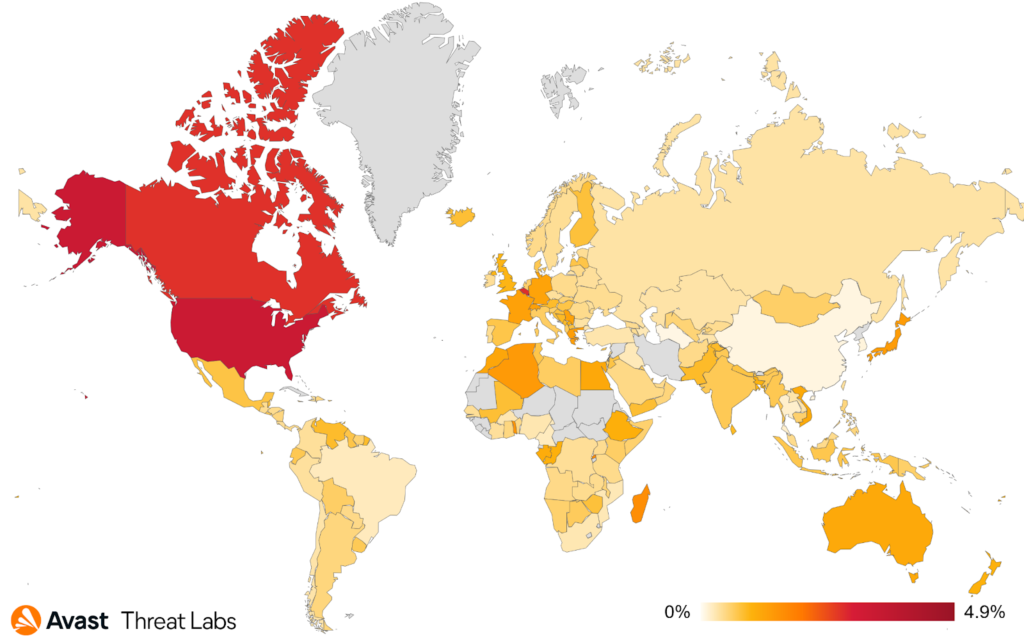

After quite an active Q4/21 that overlapped with the beginning of Q1/22, technical support scams started to decline in inactivity. There were some small peaks of activity, but the significant wave of one particular campaign came at the end of Q1/22.

According to our data, the most targeted countries were the United States and Canada. However, we’ve seen instances of this campaign active even in other areas, like Europe, for example, France and Germany.

The distinctive sign of this campaign was the lack of a domain name and a specific path; this is illustrated in the following image.

During the beginning of March, we collected thousands of new unique domain-less URLs that have one significant and distinctive sign, their url path. After being redirected, an affected user loads a web page with a well-known recycled appearance, used in many previous technical support campaigns. In addition, several pop-up windows, the logo of well-known companies, antivirus-like messaging, cursor manipulation techniques, and even sounds are all there for one simple reason: a phone call to the phone number shown.

More than twenty different phone numbers have been used. Examples of such numbers can be seen in the following table:

| 1-888-828-5604 |

| 1-888-200-5532 |

| 1-877-203-5120 |

| 1-888-770-6555 |

| 1-855-433-4454 |

| 1-833-576-2199 |

| 1-877-203-9046 |

| 1-888-201-5037 |

| 1-866-400-0067 |

| 1-888-203-4992 |

Alexej Savčin, Malware Analyst

Traffic Direction System (TDS)

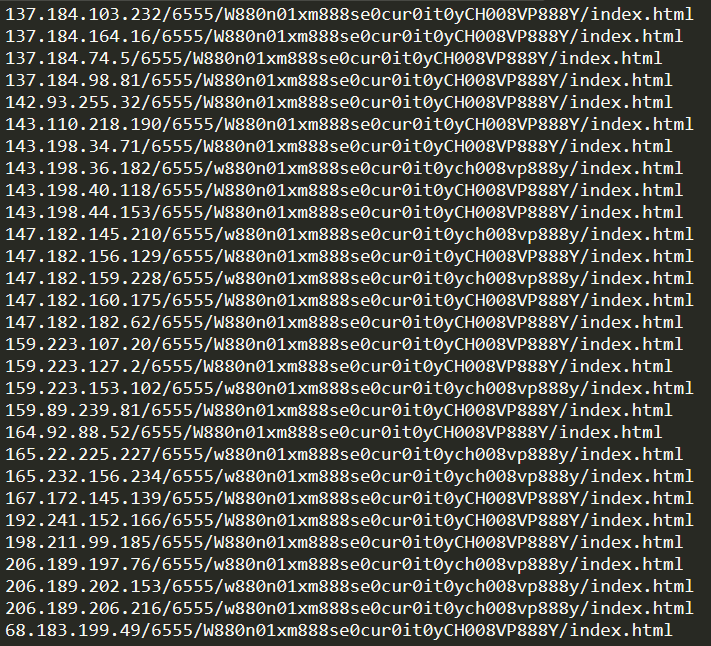

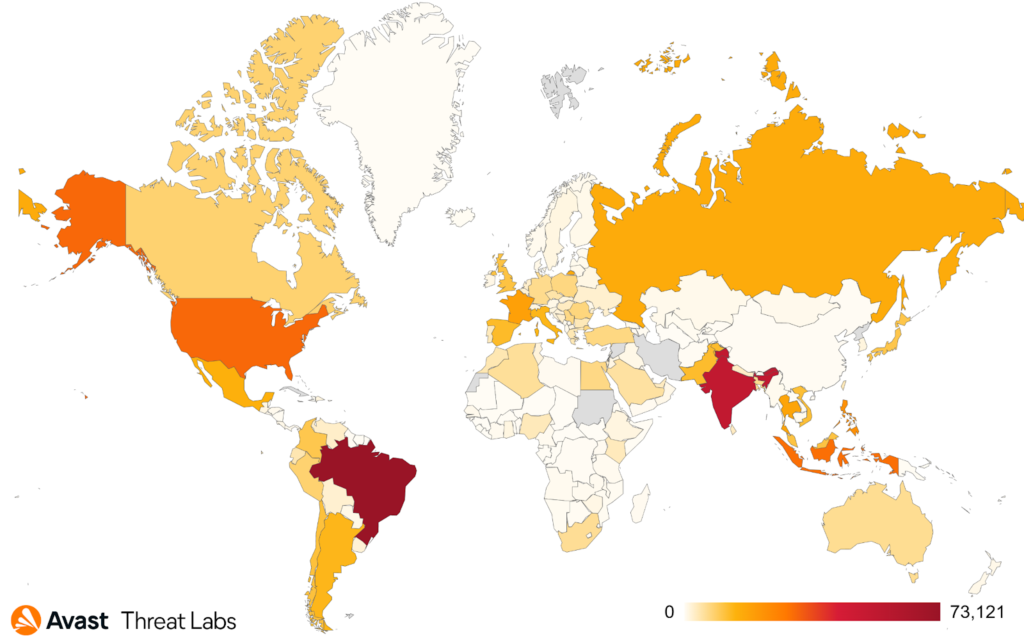

A new Traffic Direction System (TDS) we are calling Parrot TDS was very active throughout Q1/2022. The TDS has infected various web servers hosting more than 16,500 websites, ranging from adult content sites, personal websites, university sites, and local government sites.

Parrot TDS acts as a gateway for other malicious campaigns to reach potential victims. In this particular case, the infected sites’ appearances are altered by a campaign called FakeUpdate (also known as SocGholish), which uses JavaScript to display fake notices for users to update their browser, offering an update file for download. The file observed being delivered to victims is a remote access tool.

From March 1, 2022, to March 29, 2022, we protected more than 600,000 unique users from around the globe from visiting these infected sites. We protected the most in Brazil – over 73,000 individual users, in India – nearly 55,000 unique users, and more than 31,000 unique users from the US.

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

Pavel Novák, Threat Operations Analyst

Vulnerabilities and Exploits

Spring in Europe has had quite a few surprises for us, one of them being a vulnerability in a Java framework called, ironically, Spring. The vulnerability is called Spring4Shell (CVE-2022-22963), mimicking the name of last year’s Log4Shell vulnerability. Similarly to Log4Shell, Spring4Shell leads to remote code execution (RCE). Under specific conditions, it is possible to bind HTTP request parameters to Java objects. While there is a logic protecting classLoader from being used, it was not foolproof, which led to this vulnerability. Fortunately, the vulnerability requires a non-default configuration, and a patch is already available.

The Linux kernel had its share of vulnerabilities; a vulnerability was found in pipes, which usually provide unidirectional interprocess communication, that can be exploited for local privilege escalation. The vulnerability was dubbed Dirty Pipe (CVE-2022-0847). It relies on the usage of partially uninitialized memory of the pipe buffer during its construction, leading to an incorrect value of flags, potentially providing write-access to pages in the cache that were originally marked with a read-only attribute. The vulnerability is already patched in the latest kernel versions and has already been fixed in most mainstream Linux distributions.

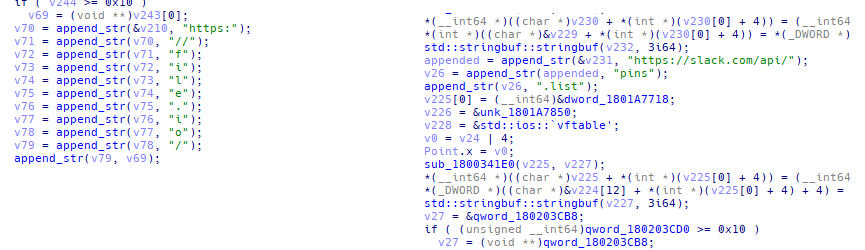

First described by Trend Micro researchers in 2019, the SLUB malware is a highly targeted and sophisticated backdoor/RAT spread via browser exploits. Now, three years later, we detected its new exploitation attack, which took place in Japan and targeted an outdated Internet Explorer.

The initial exploit injects into winlogon.exe, which will, in turn, download and execute the final stage payload. The final stage did not change much since the initial report, and it still uses Slack as a C&C server but now uses file[.]io for data exfiltration.

This is an excellent example that old threats never really go away; they often continue to evolve and pose a threat.

Adolf Středa, Malware Researcher

Jan Vojtěšek, Malware Reseracher

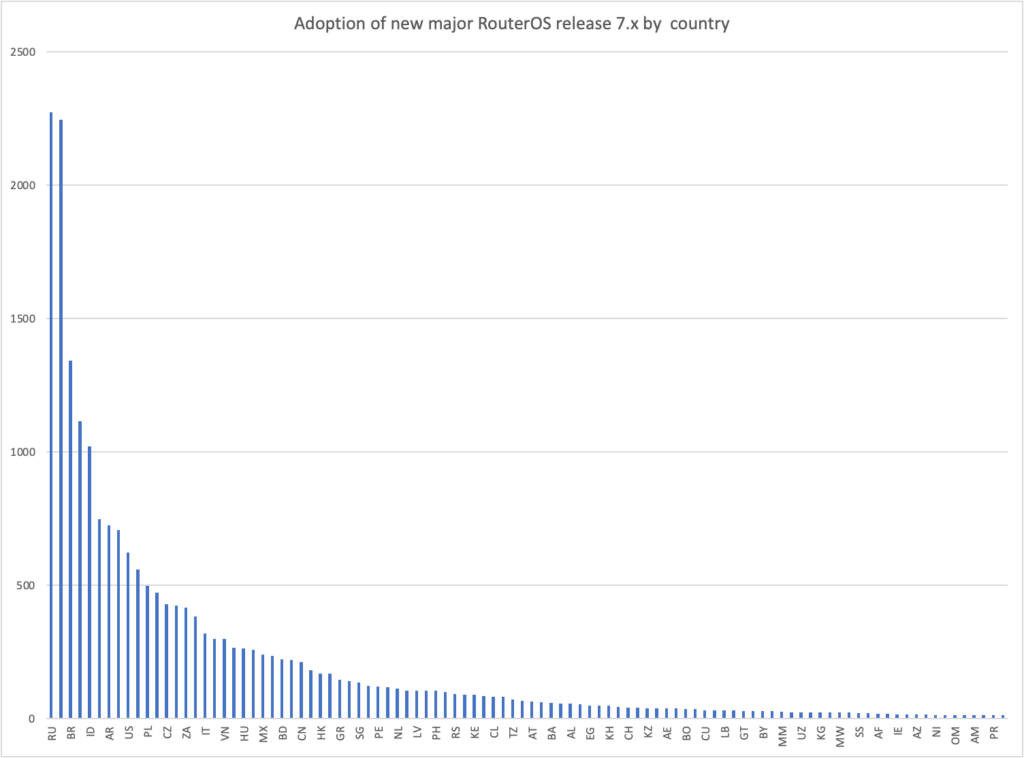

Mikrotik CVEs keep giving

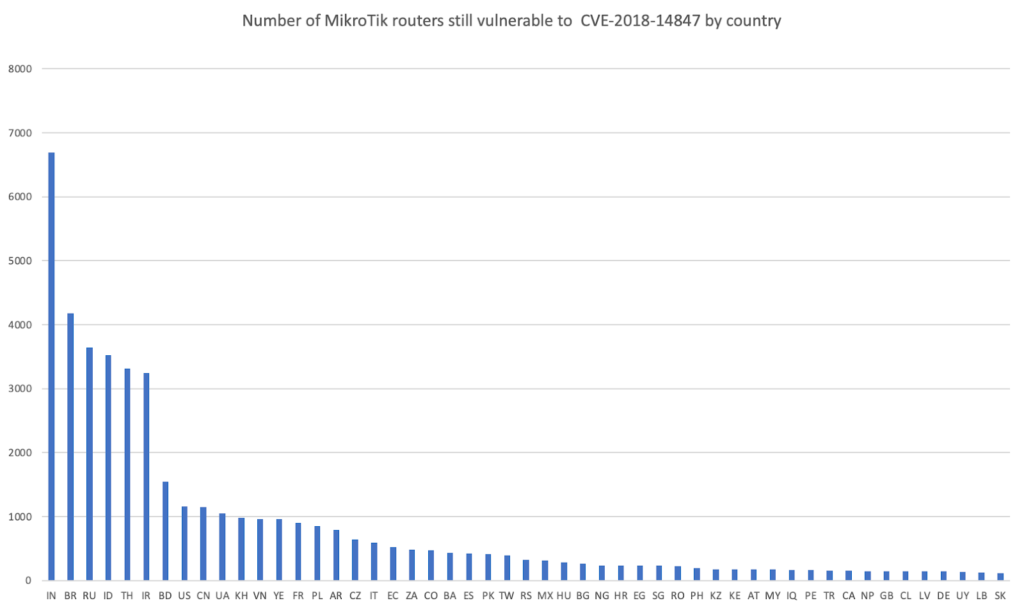

It’s been almost four years since the very severe vulnerability CVE-2018-14847 targeting MikroTik devices first appeared. What seemed to be yet another directory traversal bug quickly escalated into user database and password leaks, resulting in a potentially disastrous vulnerability ready to be misused by cybercriminals. Unfortunately, the simplicity of exploiting and wide adoption of these devices and powerful features provided a solid foundation for various malicious campaigns being executed using these devices. It first started with injecting crypto mining javascript into pages script by capturing the traffic, poisoning the DNS cache, and incorporating these devices into botnets for DDoS and proxy purposes.

Unfortunately, these campaigns come in waves, and we still observe MikroTik devices being misused repeatedly. In Q1/22, we’ve seen a lot of exciting twists and turns, the most prominent of which was probably the Conti group leaks which also shed light on the TrickBot botnet. For quite some time, we knew that TrickBot abused MikroTik devices as proxy servers to hide the next tier of their C&C. The leaking of Conti and Trickbot infrastructure meant the end of this botnet. However, it also provided us clues and information about one of the vastest botnets as a service operation connecting Glupteba, Meris, crypto mining campaigns, and, perhaps also, TrickBot. We are talking about 230K devices controlled by one threat actor and rented out as a service. You can find more in our research Mēris and TrickBot standing on the shoulders of giants.

A few days before we published our research in March, a new story emerged describing the DDoS campaign most likely tied to the Sodinokibi ransomware group. Unsurprisingly most of the attacking devices were MikroTik again. A few days ago, we were contacted by security researchers from SecurityScoreCard. They have observed another DDoS botnet called Zhadnost targeting Ukrainian institutions and again using MikroTik devices as an amplification vector. This time, they were mainly misusing DNS amplification vulnerabilities.

We also saw one compelling instance of a network security incident potentially involving MikroTik routers. In the infamous cyberattack on February 24th against the Viasat KA-SAT service, attackers penetrated the management segment of the network and wiped firmware from client terminal devices.

The incident surfaced more prominently after the cyberattack paralyzed 11 gigawatts of German wind turbine production as a probable spill-over from the KA-SAT issue. The connectivity for turbines is provided by EuroSkyPark, one of the satellite internet providers using the KA-SAT network.

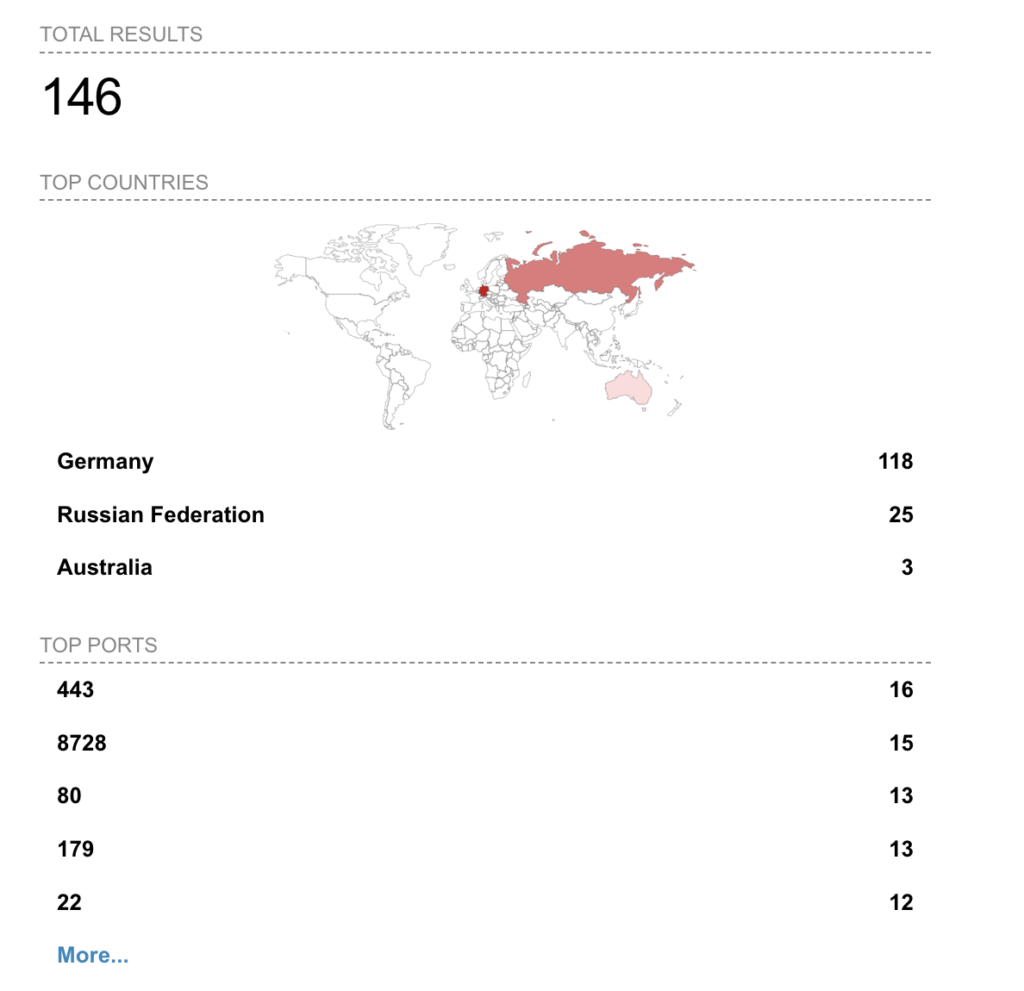

When we analyzed ASN AS208484, an autonomous system assigned to EuroSkyPark, we found 15 MikroTik devices with exposed TCP port 8728, which is used for API access to administer the devices. Also of concern, one of the devices had a port for an infamously vulnerable WinBox protocol port exposed to the Internet. As of now, all mentioned ports are closed and no longer accessible.

We also found SSH access remapped to non-standard ports such as 9992 or 9993. This is not typically common practice and may also indicate compromise. Attackers have been known to remap the ports of standard services (such as SSH) to make it harder to detect or even for the device owner to manage. However, this could also be configured deliberately for the same reason: to hide SSH access from plain sight.

From all the above, it’s apparent that we can expect to see similar patterns and DDoS attacks carried not only by MikroTik devices but also by other vulnerable IoT devices in the foreseeable future. On a positive note, the number of MikroTik devices vulnerable to the most commonly misused CVEs is slowly decreasing as new versions of RouterOS (OS that powers the MikroTik appliances) are rolled out. Unfortunately, however, there are many devices already compromised, and without administrative intervention, they will continue to be used for malicious operations repeatedly.

We strongly recommend that MikroTik administrators ensure they have updated and patched to protect themselves and others.

If you are a researcher and you think you have seen MikroTik devices involved in some malicious activity, please consider contacting us if you need help or consultation; since 2018, we have built up a detailed understanding of these devices’ threat landscape.

Martin Hron, Malware Researcher

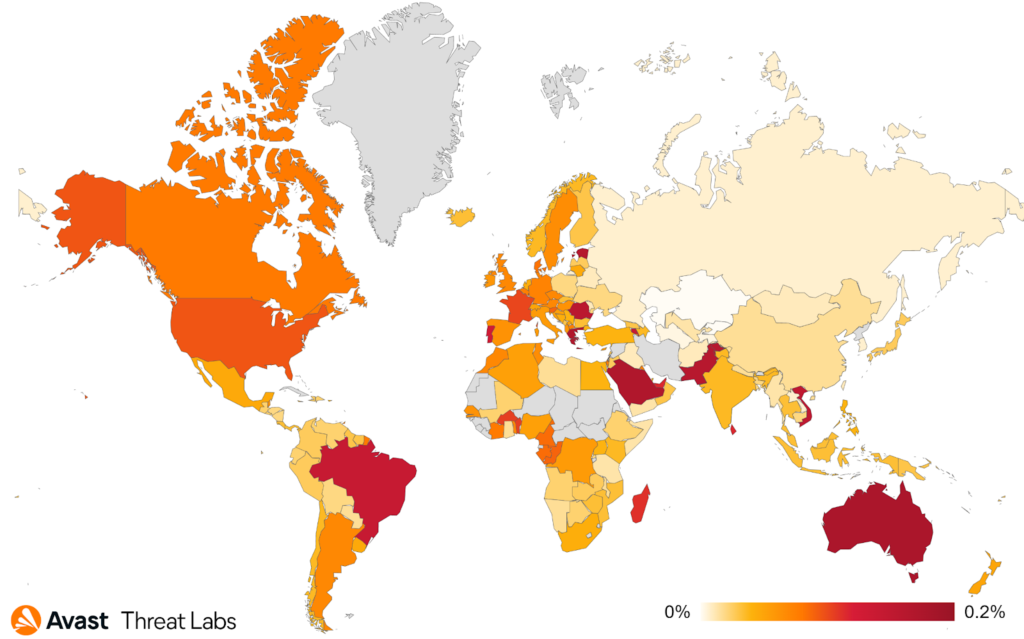

Web skimming

In Q1/22, the most prevalent web skimming malicious domain was naturalfreshmall[.]com, with more than 500 e-commerce sites infected. The domain itself is no longer active, but many websites are still trying to retrieve malicious content from it. Unfortunately, it means that administrators of these sites still have not removed malicious code and these sites are likely still vulnerable. Avast protected 44k users from this attack in the first quarter.

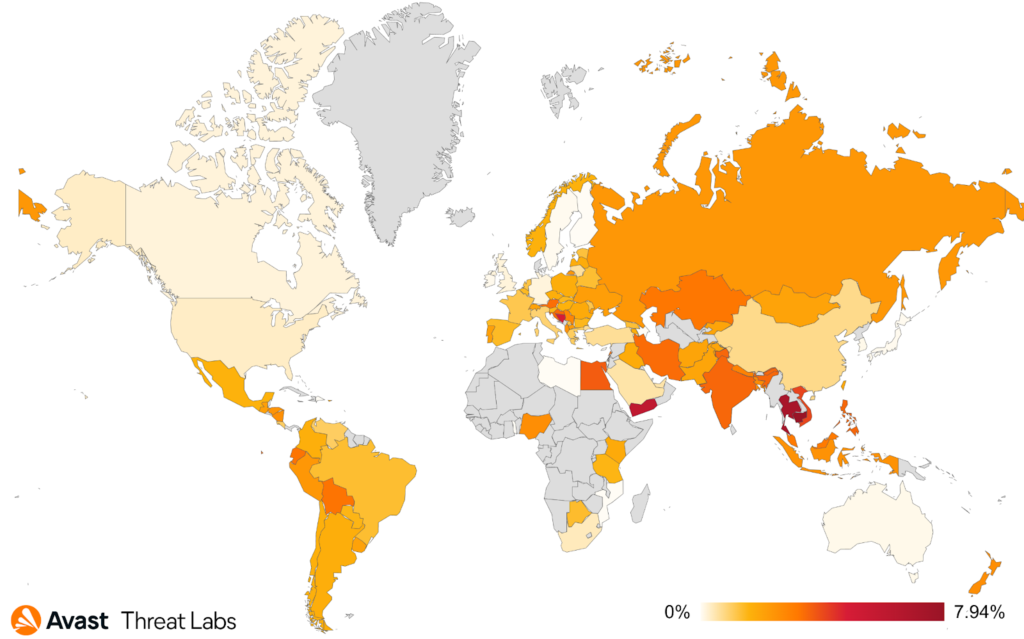

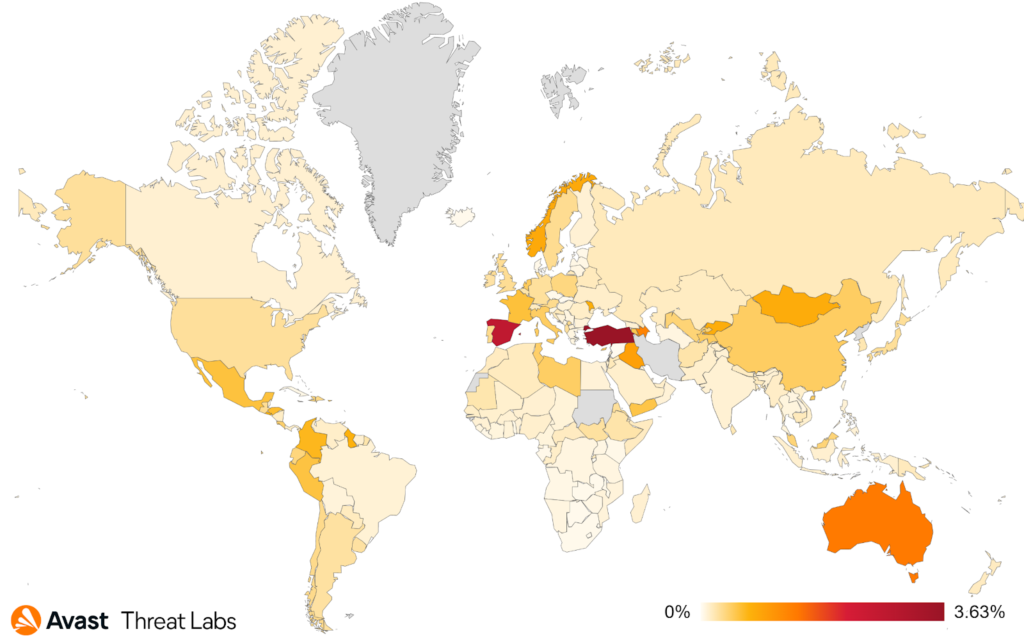

The heatmap below shows the most affected countries in Q1/22 – Saudi Arabia, Australia, Greece, and Brazil. Compared to Q4/21, Saudi Arabia, Australia and Greece stayed at the top, but in Brazil, we protected almost two times more users than in the previous quarter. However, multiple websites were infected in Brazil, some with the aforementioned domain naturalfreshmall[.]com. In addition, we tweeted about philco.com[.]br, which was infected with yoursafepayments[.]com/fonts.css. And last but not least, pernambucanas.com[.]br was also infected with malicious javascript hidden in the file require.js on their website.

Overall the number of protected users remains almost the same as in Q4/21.

Pavlína Kopecká, Malware Analyst

Mobile-Related Threats

Adware/HiddenAds

Adware maintains its dominance over the Android threat landscape, continuing the trend from previous years. Generally, the purpose of Adware is to display out-of-context advertisements to the device user, often in ways that severely impact the user experience. In Q1/22, HiddenAds, FakeAdblockers, and others have spread to many Android devices; these applications often display device-wide advertisements that overlay the user’s intended activity or limit the app’s functionality by displaying timed ads without the ability to skip them.

Adware comes in various configurations; one popular category is stealthy installation. Such apps share common features that make them difficult for the user to identify. Hiding their application's icon from the home screen is a common technique, and using blank application icons to mask their presence. The user may struggle to identify the source of the intrusive advertisements, especially if the applications have an in-built delay timer after which they display the ads. Another Adware tactic is to use in-app advertisements that are overly aggressive, sometimes to the extent that they make the original app’s intended functionality barely usable. This is common, especially in games, where timed ads are often shown after each completed level; frequently, the ad screen time greatly exceeds the time spent playing the game.

The Google Play Store has previously been used to distribute malware, but recently, actors behind these applications have changed tactics to use browser pop-up windows and notifications to spread the Adware. These are intended to trick users into downloading and installing the application, often disguised as games, ad blockers, or various utility tools. Therefore, we strongly recommend that users avoid installing applications from unknown sources and be on the lookout for malicious browser notifications.

According to our data, India, the Middle East, and South America are the most affected regions. But Adware is not strictly limited to these regions; it’s prevalent worldwide.

As can be seen from the graph below, Adware’s presence in the mobile sphere has remained dominant but relatively unchanged. Of course, there’s slight fluctuation during each quarter, but there have been no stand-out new strains of Adware as of late.

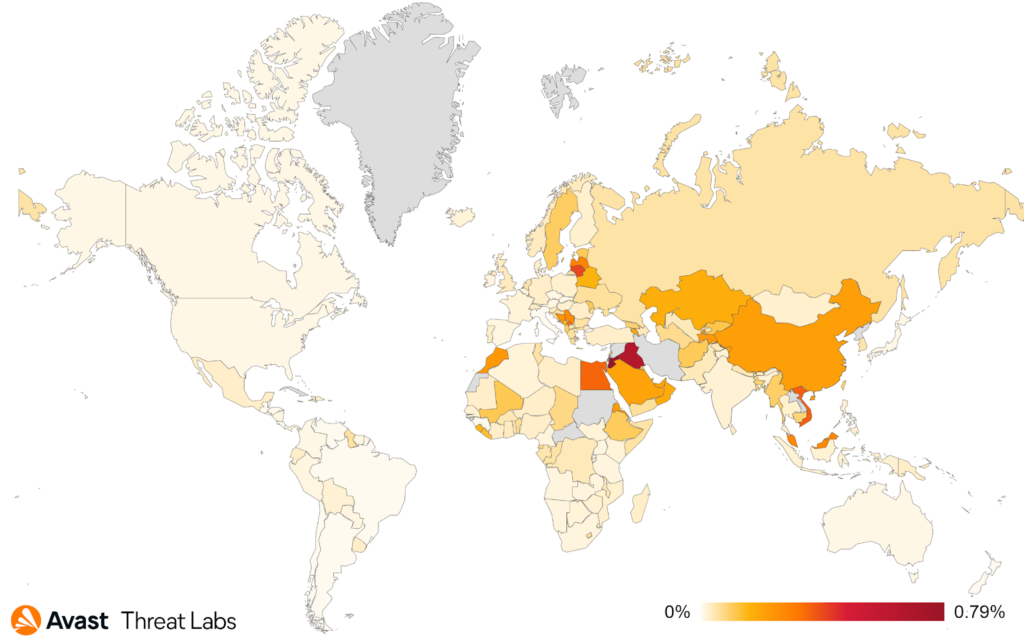

Bankers

In Q1/2022, some interesting shifts were observed in the banking malware category. With Cerberus/Alien and its clones still leading the scoreboard by far, the battle for second place has seen a jump, where Hydra replaced the previously significant threats posed by FluBot. Additionally, FluBot has been on the decline throughout Q1..

Different banker strains have been reported to use the same distribution channels and branding, which we can also confirm observing. Many banking threats now reuse the proven techniques of masquerading as delivery services, parcel tracking apps, or voicemail apps.

After the departure of FluBot from the scene, we observed an overall slight drop in the number of affected users, but this seems only to be returning to the numbers we’ve observed in the last year, just before FluBot took the stage.

Most targeted countries remain to be Turkey, Spain and Australia.

PremiumSMS/Subscription scams

While PremiumSMS/Subscription related threats may not be as prevalent as in the previous years, they are certainly not gone for good. As reported in the Q4/21 report, a new wave of premium subscription-related scams keeps popping up. Campaigns such as GriftHorse or UltimaSMS made their rounds last year, followed by yet another similar campaign dubbed DarkHerring.

The main distribution channel for these seems to be Google Play, but they have also been observed being downloaded from alternative channels. Similar to before, this scam preys on the mobile operator’s subscription scheme, where an unsuspecting user is lured into giving out their phone number. The number is later used to register the victim to a premium subscription service. This can go undetected for a long time, causing the victim significant monetary loss due to the stealthiness of the subscription and hassle related to canceling such a subscription.

While the primary target of these campaigns seems to remain the same as in Q4/21 – targeting the Middle East, countries like Iraq, Jordan, but also Saudi Arabia, and Egypt – the scope has broadened and now includes various Asian countries as well – China, Malaysia and Vietnam amongst the riskiest ones.

As can be seen from the quarterly comparisons in the graph below, the spikes of activity of the respective campaigns are clear, with UltimaSMS and Grifthorse causing the spike in Q4/21. Darkherring is behind the Q1/22 spike.

Ransomware/Lockers

Ransomware apps and Lockers that target the Android ecosystem often attempt to ‘lock’ the user’s phone by disabling the navigation buttons and taking over the Android lock screen to prevent the user from interacting with the device and removing the malware. This is commonly accompanied by a ransom message requesting payment to the malware owner in exchange for unlocking the device.

Among the most prevalent Android Lockers seen in Q1/22 were Jisut, Pornlocker, and Congur. These are notorious for being difficult to remove and, in some cases, may require a factory reset of the phone. Some versions of lockers may even attempt to encrypt the user’s files; however, this is not frequently seen due to the complexity of encrypting files on Android devices.

The threat actors responsible for this malware generally rely on spreading through the use of third party app stores, game cheats, and adult content applications.

A common infection technique is to lure users through popular internet themes and topics – we strongly recommend that users avoid attempting to download game hacks and mods and ensure that they use reputable websites and official app stores.

In Q1/22, we’ve seen spikes in this category, mainly related to the Pornlocker family – apps masquerading as adult content providers – and were predominantly targeting users in Russia.

In the graph above, we can see the spike caused by the Pornlocker family in Q1/22.

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Jakub Vávra, Malware Analyst

Acknowledgements / Credits

Malware researchers

- Adolf Středa

- Alexej Savčin

- Anh Ho

- David Álvarez

- Igor Morgenstern

- Jakub Křoustek

- Jakub Vávra

- Jan Holman

- Jan Rubín

- Ladislav Zezula

- Luigino Camastra

- Martin Chlumecký

- Martin Hron

- Ondřej David

- Pavel Novák

- Pavlína Kopecká

- Samuel Sidor

- Vladimir Martyanov

- Vladimír Žalud

Data analysts

- Pavol Plaskoň

Communications

- Dave Matthews

- Stefanie Smith