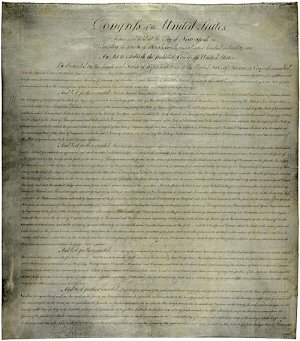

Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 created the federal court system outlined in Article III of the United States Constitution. Article III only authorizes "one supreme Court," but gives Congress the power to create "inferior Courts...from time to time."[1]

Since the federal court system was being created from scratch, writing the Judiciary Act of 1789 was a monumental task. In addition to creating federal courts, the Act also created the positions of United States Attorney General, United States Attorney, United States Marshal and Clerk of Court. These four positions still exist and have been expanded upon in the modern United States.[2]

The Judiciary Act of 1789 was signed into law by President George Washington on September 24, 1789.[3] That same day, President Washington nominated John Jay to serve as the first Chief Justice of the newly-created Supreme Court of the United States.[4]

Achievements of the Act

The Judiciary Act created the three-tiered structure of the United States federal court system. In addition to creating these courts, the Act defined the jurisdiction of each tier of court.

Supreme Court

Structure

The Supreme Court, the only court specified by the Constitution, was authorized to have a Chief Justice and five associate justices.[2]

Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction. Allowing the court to hear appellate decisions from the state Supreme Courts was controversial, but was authorized if the question regarded the constitutionality of state or federal law.[2]

Circuit Court

Structure

The Circuit Courts were created as the trial courts of the federal judiciary. These courts were presided over by two Supreme Court justices and a local district judge. Supreme Court justices were assigned to hear cases in one of three circuits and had to travel throughout the region, known as "circuit riding."[2]

Circuit riding continued until the Evarts Act of 1891 created the Circuit Courts of Appeals, though the practice was limited by the Judiciary Act of 1869. However, the legacy of circuit riding still exists today, with each justice of the Supreme Court assigned to a circuit.[5]

Jurisdiction

The Circuit Courts had limited appellate jurisdiction, in addition to general jurisdiction. According to the Federal Judicial Center, authorizing the Circuit Courts to hear cases between parties from different states greatly strengthened the federal judiciary.[2]

District Court

Structure

A district court was created in each state, in addition to Kentucky and Maine. Each court had one judge.[6][2]

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of these courts focused primarily on admirality and maritime cases, but the court could also hear cases against consuls or vice consuls. Limiting the jurisdiction of the District Courts was important to opponents of the Judiciary Act who did not want the federal courts to have too much authority.[7]

Attorney General

The position of Attorney General was established by the Act, which called for an individual to "prosecute and conduct all suits in the Supreme Court in which the United States shall be concerned..."[8] Edmund Jennings Randolph was the first Attorney General of the United States. He was appointed by President Washington two days after the Judiciary Act became law.[9]

Support staff

The Act also created the positions of Clerk of Court, United States Attorney and United States Marshal.[10][11] In the modern judiciary, a Clerk of Court oversees the administration of each court, a United States Attorney serves in each district to represent the district's interests in court, and the United States Marshals provide security for judges.

Crafting the Act

The primary author of the Judiciary Act was Senator Oliver Ellsworth. Ellsworth was also responsible for suggesting a bicameral Congress with equal representation for the states during the drafting of the Constitution and served as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1796 to 1800.[12]

Ellsworth had help with the Act from a committee, which is considered the precursor to the Senate Judiciary Committee.[13] Senator William Paterson, of New Jersey, is also credited with crafting the Judiciary Act.[2]

Senate at the time

The new Senate convened for the first time on March 4, 1789; on April 7, 1789, a committee to consider the federal judiciary was formed.[14] When the Judiciary Act was written, there were only twenty Senators serving, as New York had not yet elected its Senators and Rhode Island and North Carolina had not yet ratified the Constitution.[15]

At the time of the first Senate, the body was expected merely to review legislation from the House of Representatives. The Judiciary Act was one exception to this assumption, as it was almost wholly crafted in the Senate.[12]

Support for the Act

The main group of supporters of the Judiciary Act were the Federalists, the party which argued for a strong federal government. Led by James Madison, the Federalists argued that Article III of the Constitution implored the Congress to create the lower court system to reinforce the document's supremacy over state law. Another essential component of the federal court system would be to arbitrate disputes involving states or citizens from different states, in addition to crimes against the United States.[7]

Federalists also believed that federal courts would be less biased than state courts, since jurors would be drawn from all over the region, as opposed to the local area.[7]

Opposition to the Act

The main opposition to the Judiciary Act came from the Anti-Federalists, the party which favored the autonomy of the states. Anti-Federalists objected to the creation of the district courts, arguing that review of state court decisions by the Supreme Court would be sufficient.

Vocal Anti-Federalists who served on the committee to create the Act were Richard Henry Lee (of Virginia) and William Maclay (of Pennsylvania).[11] In the House, Representative Samuel Livermore was adament about limiting the jurisdiction of the district court to cases involving admiralty. The eventual limited jurisdiction of those courts was a compromise to appease Anti-Federalists.[7]

| “ | I opposed this bill from the beginning...The constitution (sic) is meant to swallow all the state constitutions, by degrees; and this to swallow, by degrees, all the State judiciaries." --Sen. William Maclay[7] [16] | ” |

While the Judiciary Act was being created and debated, Anti-Federalists were also focusing on the adoption of the Bill of Rights. The first ten amendments to the Constitution were considered integral for protecting individual liberties from the intrusion of a strong federal government.[17]

Judiciary Act becomes law

The Senate passed the Judiciary Act on July 17, 1789 with a vote of 14 to 6. The House of Representatives debated the bill on seven different days and passed it without a roll call vote on September 17, 1789.

President Washington signed the Judiciary Act of 1789 into law on September 24, 1789.[3]

See also

External links

- Federal Judicial Center, Landmark Judicial Legislation: The Judiciary Act of 1789

- American Memory, An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States pages 2239-2256

- American Memory, The Judiciary Bill Documents related to the Judiciary Act of 1789

- United States Senate, Senator Ellsworth's Judiciary Act

- Duke Law Journal, "To Establish Justice": Politics, The Judiciary Act of 1789, And the Invention of the Federal Courts by Wythe Holt

Footnotes

- ↑ Article III

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Federal Judicial Center, Landmark Judicial Legislation: The Judiciary Act of 1789

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Library of Congress, Judiciary Act of 1789

- ↑ John Jay

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, Geographical Boundaries of the United States Court of Appeals and United States District Courts, as of July 2010

- ↑ Judiciary Act of (1789) - Further Readings

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Judiciary Act of (1789) - Further Readings

- ↑ United States Department of Justice, About the Office of Attorney General

- ↑ United States Department of Justice, Edmund Jennings Randolph

- ↑ U.S. Marshals Service, History - The First Generation of United States Marshals

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 U.S. District Court--NH: Preface, Acknowledgment and Introduction

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 United States Senate, Senator Ellsworth's Judiciary Act

- ↑ United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, History of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary

- ↑ United States Senate, The Significance of March 4

- ↑ US Constitution, Ratification Dates and Votes

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ History.com, Bill of Rights is finally ratified