In partnership with Epic Magazine.

This is the first installment of a three-part story. In part two, with their passports confiscated and heroin withdrawal setting in, they ask a team of mercenaries for help. In part three, their situation only gets bleaker — until a relapse and a sudden death set the stage for an unlikely breakthrough. Skip to: Part 2 | Part 3

Prologue

Patrick Allocco Jr. was drunk and confused, sprinting through the back alleys of Luanda, Angola, a place he barely knew. He’d been out partying with some new friends, Osvaldo and Erickson, at Club Mega Bingo, a night club of choice among the lucky Angolan youth who had real money to spend. Patrick Jr. had shared late nights out with these guys before and always had a good time. The place was big, with flashing lights and a heaving dance floor overlooked by a DJ playing hip-hop, reggaeton, and kizomba, a local genre of romantic rhythms. Patrick Jr. liked hanging out with his new circle — he and Erickson had become particularly close — but on this night, something had gone wrong.

The way Patrick Jr. remembers it, there was a guy he’d never seen before, Danilo, who was massively built, bald, and humorless. In the bar, Patrick Jr. had gotten pretty well lubricated, but people kept insisting on more drinks. Have another. I’m good right now. But you must! I’m all right, really. Just one more, my friend. Patrick Jr. noticed that Danilo was glaring and getting uncomfortably close — behind him, next to him, towering over him. The night went from fun to a little weird to alarming, and Patrick Jr. got nervous and left through a rear door. There, he got into a scuffle with security, who picked him up by the belt and tossed him out, like it was an Old West saloon. His shirt was torn, so Patrick Jr. shook it off and started walking. Then he noticed Danilo following with Osvaldo in tow. Patrick Jr. heard them running, and before he knew it, he was running too.

He kept turning corners, trying to lose his pursuers in the warren of small, dark streets. He cut left, then left again. Dead end. Panicked, he looked around and saw a small opening in the fence; beyond, it was pitch dark. He climbed through. A few steps in, Patrick’s feet went out from under him and he plunged through a broken grate into a sewer. Or maybe a drainage channel. He didn’t want to think about the precise source of the water as he lowered himself to his chin, hiding from Danilo’s approach, his keys jangling as he got closer, calling to Patrick Jr. that he would find him.

Submerged in the dark, Patrick Jr. was well concealed when Danilo and Osvaldo walked right by. He waited and listened for the sound of Danilo’s keys to recede. Neck deep in filthy water, he considered his situation. A few months earlier, he had been a homeless heroin addict in New Jersey. His father, a broke music promoter, had convinced him they could turn their lives around by arranging a complicated but lucrative hip-hop concert on New Year’s Eve in Angola. It was more complicated than they’d imagined. Things went awry, the authorities took their passports, and now they were on the hook for a lot of money. The guy they owed was a local promoter known for his clout and coercion; there were stories about his detaining or extorting other hip-hop artists, from Fat Joe to Ja Rule and DMX. The Alloccos couldn’t leave until they paid back this guy’s money, which they didn’t have. They had been stuck in Angola for weeks. And now Patrick Jr. was hiding in a sewer, completely lost.

And nearly naked. When it was finally quiet and he hoisted himself out of the water, his pants caught on something and slipped off, along with his shoes. He managed to grab his shoes, but his pants were gone, along with his wallet, phone, and keys. So Patrick Jr. was wearing only wet sneakers and underwear as he climbed up the wall of the dead end and started walking across the sheet-metal roofs, looking for a way out.

He could hear people below talking in their houses. And he could hear Osvaldo and Danilo every so often in the distance. It was slow going on the roofs, which were thin and clanged easily. Patrick Jr. treaded carefully, searching for beams — until a misstep sent him crashing right through a ceiling.

There was immediate chaos. He had landed in someone’s closet at 4:30 in the morning in his flannel boxers. A father jumped out of bed, also in his underwear. The entire household was awake instantly, yelling. “I’m sorry about your roof!” Patrick Jr. said, dazed but uninjured. There were children crying, there was an agitated grandmother. Patrick Jr. tried to keep everyone’s voices down and offered to pay for repairs. “Get out!” the father yelled, dragging Patrick Jr. to the door, where Danilo and Osvaldo were waiting.

Danilo knocked Patrick Jr. to the ground. “I knew we’d find you,” he said. Patrick Jr. was still trying to understand what was even happening. Osvaldo had been his friend. They’d gone to see movies, spent the day at the beach on Ilha do Cabo. “How much are you worth to your father?” Danilo said. “Get us money, or you’re never going home.” Now Patrick Jr. got it. I’m already captive here, he thought, and now a shakedown?

Patrick Jr. sensed that this was Danilo’s idea and couldn’t tell if Osvaldo was in on it, going along in the moment, or maybe even trying to help. Either way, Patrick Jr. felt betrayed. “I thought we were brothers,” he said to Osvaldo.

Danilo wrapped his belt around Patrick’s arm to drag him along. Patrick Jr. was still shirtless, so Danilo put his vest on him, which felt like an odd touch. “Tell your father we want a million dollars,” Danilo said. But Osvaldo knew his father didn’t have that much money. So as Patrick Jr. was being paraded in his underwear and Danilo’s vest, he listened to them arguing about the ransom.

“What about half a million?”

“I told you, they don’t have that.”

Soon, Danilo’s demand was $10,000. Patrick Jr., both amused and annoyed that Danilo came down so fast on his price, explained that his father didn’t have even that much.

“Fuck you,” Danilo said. “Get us that money.”

Danilo dragged Patrick Jr. along the street. “You’re never going home unless I get that money,” Danilo said. Then Patrick Jr. saw that they were near the U.S. Embassy. He knew it well from the times he and his father had been there, hoping American officials could intervene on their behalf and get them out of the country. He knew there were Marines there. Patrick Jr. went limp, using all his dead weight to drag Danilo down with him, while yelling, “Help!” Soon they were surrounded by embassy guards.

The Americans took Patrick Jr. to the embassy’s security booth, where he sat in his underwear (and Danilo’s vest). He didn’t recognize any of the guards on this shift. They tried to figure out the commotion: “What happened?”

Where to begin? He started to explain. But the way Patrick Jr. wound up there, scratched and bruised, was a misadventure full of so much bizarre detail, folly, and general confusion it sounded like a farce. The guards just needed the basics. “Who are you?” one asked.

“My name is Patrick Allocco Jr.,” he said. “My father is Patrick Allocco Sr. And we are trapped in Angola.”

Chapter 1

Patrick Allocco Sr. was down and out. He had been a real-estate speculator, a campaign manager, and a music promoter, all of which were self-created jobs he describes as “professional crisis management.” These days, there seemed to be more crisis than management. An arrangement with “the Barry Manilow of Spain” had blown up in Las Vegas. A tour with Juan Gabriel was successful until a double cross in Mexico. He brought Bon Jovi to Puerto Rico for an appearance at a mostly empty stadium and came home in debt. It wasn’t always that way — sometimes he’d done well for himself. But Patrick Sr. had always seemed to choose fickle businesses. Good money one year and nothing the next. In the 1980s, he’d picked up Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, felt inspired, and went out and made a hundred grand in six weeks — only to lose it all on Black Monday.

That kind of setback would paralyze most people. Not Patrick Sr. When one venture went south, he’d jump into something new, convinced that the next big score was just around the bend. He’d always had hustle. While still in high school, in Morristown, New Jersey, he started a photography business, which drew politician clients, which led to campaign jobs. He worked for congressmen, Senate candidates, New Jersey governor Tom Kean. He was good at building relationships. People liked talking to him. And he liked talking people into things.

Patrick Sr., who was born in 1960, was still in his 20s when he got married and learned he was having a child — although not in that order. Another surprise, taken in stride. His bride was a feisty brunette named Joellen, whom he’d gotten to know at Upstairs, Downstairs, his uncle’s restaurant in Morristown. Their son — Patrick Jr., born in 1989 — was a joy, but the same was not true of the marriage. Joellen was charming and lively and well liked, but she was in the early stages of addiction. She’d disappear on benders and then try to make good at AA meetings. Until one day she left him for someone from one of those meetings. Patrick Sr. was crushed. They divorced after a year.

For a time, they shared custody, but eventually Joellen fell into full-time addiction. She lost her job, stole money, got arrested. At one point, she took a police vehicle and was chased nine miles up the New Jersey Turnpike. By the time Patrick Jr. was 6, she was in jail; after her release, she would stay out of trouble for periods of time, but mostly Patrick Sr. raised his son by himself. You rarely saw one without the other. Patrick Sr. would take his son to his family’s shore house in the summers and fly him around in the Cessna he’d bought after taking pilot lessons.

Patrick Sr. was working in ad sales at Dow Jones, doing well but feeling the itch to strike out on his own. He’d gotten his first taste of music promotion when he arranged for Don McLean to play a concert at Upstairs, Downstairs. He followed that with McLean at Carnegie Hall. Patrick Sr. made money on the former, lost money on the latter. Nevertheless, he was drawn to the business. Music promotion, he discovered, was an unpredictable market where you could generate a windfall or lose a lot in a flash. Naturally, he left his job and mortgaged his house to put money into his own promotion company, Allgood Entertainment.

Success in Patrick Sr.’s new trade required pluck, luck, and cash. It was a patchwork business, regionally operated, with strange characters and opaque rules. To put together a show, you had to know people and know how to trade favors. It was a place of prospectors and fast talkers. Patrick Sr. fit right in.

By then, he was married again, this time to Abby, an interior decorator whose even temperament made for good ballast to his manic energy. Abby was one of seven siblings (five of whom, including her, formed a quintuplet), and she had accustomed herself to domestic chaos by becoming unflappable. Abby was drawn to Patrick Sr.’s eternal optimism, but was dubious about his work in the music business — “They’re all liars and thieves,” she said — but she was not the type to put her foot down. Besides, she knew how much he loved it.

For a time, Patrick Sr.’s company did well. He brought the Temptations to the Beacon Theatre in New York, organized shows by Blues Traveler, and put James Brown onstage at Convention Hall in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Patrick Sr. loved watching the audience file in and the feeling at the start of a show, when the lights go down and people light up.

Concert promotion was often not about one’s personal taste; the job was to sell whatever you could — like when he put on a Radio Disney show with Lindsay Lohan and Hulk Hogan. Or when he took Menudo on tour or worked with Julio Iglesias. This gave Patrick Sr. the idea to bring on a partner who spoke Spanish and head south with American acts, like Stevie Wonder. He helped organize a jazz festival in Tobago, where he booked Elton John, Shakira, and Sting. (The Tobago Jazz Festival was not necessarily for purists.) As Patrick Jr. got older, he’d join his father at the shows, working as a gofer, manning the ticket booth, or figuring out how to get nine dozen freshly laundered bath towels at a moment’s notice because Earth, Wind & Fire showed up in Asbury Park and asked for nine dozen bath towels.

But the money could be inconsistent. With a big-name act, margins were smaller because the artists kept a larger share of the proceeds, and having a global audience didn’t guarantee success. Case in point was that Bon Jovi concert in Puerto Rico — it had cost Patrick Sr. more than $50,000.

Still, the big gigs were the most enticing. Patrick Sr. came this close to putting on the show of shows — a Michael Jackson concert, which he scored after sweet-talking his way into a conversation with Joe Jackson in Las Vegas — and started putting it together. But then Michael Jackson signed a deal with AEG to do 50 shows in London instead. And then he died. Patrick Sr. lost everything he’d invested, which was everything, and it was in that aftermath that he found himself cooking meals on a camping stove in his kitchen and using a kettle to heat bath water. He couldn’t pay the electricity bill. Patrick Sr. sat in his living room on a lounge chair in front of a television he couldn’t turn on, facing failure. By the fall of 2011, he was $1.2 million in debt.

He’d also been going through a difficult time with his son. Patrick Jr. had started drinking young, then followed his mother’s path into drugs. Patrick Sr. tried to help but was unsure how. That November, Patrick Jr. overdosed in his father’s home, and Patrick Sr. told his son he couldn’t stay with him anymore. It’s hard to say to your only child that he is unwelcome, but Patrick Sr. felt cornered. For the first time, Patrick Jr. didn’t put up a fight. He took his things and left.

Patrick Sr. was about to lose the house anyhow. The only moneymaking gigs he had going were a couple of tours with Colombian comedians, one of which had such a skeleton crew that Patrick Sr. was in charge of firing the confetti cannon. (He never got the timing right.) One night, as he was waiting for his cue, someone texted him a picture of Patrick Jr. on the street, panhandling. How did it come to this? Patrick Sr. thought. While his son was wandering in the cold, begging for money, here he was, crouching in the wings of a shitty theater, firing a confetti cannon over the heads of two unknown stand-ups.

But if there ever was an optimist, it was Patrick Allocco Sr. For him, life was always one daring enterprise away from a complete reversal. And in early December an opportunity emerged.

Patrick Sr. heard that an Angolan entertainment mogul named Henrique Miguel, who went by “Riquinho,” needed a big act at the last minute for New Year’s Eve. Patrick Sr. knew people in the music business had made a lot of money working with him. “Riquinho is a big spender,” his friend Peter Seitz, a manager and agent, said. Another promoter, David Osborn, explained that Riquinho was powerful, with pull in the local government, and could put shows together quickly.

Patrick Sr. also heard rumors that Riquinho could be difficult and unpredictable. But if he could somehow deliver an A-list performer from the U.S., the fee could be as much as $100,000. It was a long shot, but it was the only shot he had.

Using the internet at a friend’s house, he reached Riquinho. “I look forward to doing business with you,” Patrick Sr. wrote. He quickly discovered that Riquinho’s first choice, Lil Wayne, was unavailable. And his first few backups, like Nicki Minaj, were booked. Eventually, Riquinho suggested Nas, and after several days of effort Patrick Sr. managed to get the rapper’s manager on the phone. Incredibly, Nas was available. Patrick Sr. spoke to Riquinho on the phone with a Portuguese-speaking acquaintance translating, and a deal was struck.

There would be two concerts — one large stadium show on New Year’s Eve and a smaller show the next day for VIPs: wealthy Angolans, insiders, government people. Two hours of stage time total for just over half a million dollars. Patrick Sr. couldn’t believe his luck. Nas’s fee would be $300,000, leaving plenty of margin even after hiring an opening act and paying for travel and other expenses. Riquinho would pay up front and secure the venue himself. All Patrick Sr. had to do was play middleman.

When payment arrangements came up, however, there was a hitch. Nas would not fly to Angola without getting his fee up front, but Riquinho wouldn’t send the money until Nas arrived. Riquinho had been burned before by musical acts who didn’t show. It was an understandable position.

Patrick Sr. was in a bind. And yet he was tingling with desire to make this work. He got back on the phone with Riquinho, who said he would wire the money in advance if Patrick Sr. could furnish some kind of collateral. Patrick Sr. couldn’t turn on his lights. The risk was enormous, but he was unfazed. All he thought was: Where am I going to find that collateral?

Chapter 2

Patrick Jr. faced another miserable morning. He woke up in a tent, cold and already jonesing. He and eight others had bedded down in one of the several dozen anti-capitalist bivouacs that made up the Occupy Newark encampment. Patrick Jr. had gone there because he’d heard there was free food. And it was close to his drug dealer, which was convenient. It was early December, and a deep cold snap kept everyone huddling together for warmth. At night, the steady rasp of sneezes and coughs gave the tent the feeling of an infirmary, Patrick Jr. thought, or a detachment of doomed infantry in the Revolutionary War.

Patrick Jr. was sick in both senses; he was trying to keep down opiate-withdrawal pills while managing a rumbling cough. Although that didn’t stop him from stepping out for a cigarette. Patrick Jr. unzipped the tent and put on his one item of personal value, a rabbit-fur bomber hat. He lit a Camel and wandered over to a tree. This was the nicest part of his day: peeing in the middle of Military Park, ear flaps down, watching the traffic go by.

The rest of the day was spent panhandling and scoring. He’d figured out that the corners of midtown Manhattan were more lucrative than those in New Jersey, so he would take the PATH train to 33rd Street and sit outside Macy’s with a cup and a sign: HOMELESS, HUNGRY, GOD BLESS. Most people ignored the panhandlers, and it was a punishing feeling, watching so many strangers look right through you. But Patrick Jr.’s ragged condition couldn’t completely hide his boyish, sympathetic face. On a good day, he’d make $100. Sometimes people stopped and talked, like the woman who gave him some mangoes, or the pastor from Texas who took him to dinner, treated him with dignity. A wealthy woman with a Louis Vuitton bag sat down and talked to him for two hours, mostly about her divorce and how unhappy she was. Everyone has it hard, Patrick Jr. thought. Eventually she asked: “How did you end up here?”

It was a good question, one Patrick Jr. wasn’t sure how to answer. It had been quite some time since the tender days when Patrick Jr. and his father laid out in three inches of fresh snow, tufted into winter sleeping bags, watching shooting stars together. Patrick Jr. was 11 then, and they were on one of many Boy Scout trips where his father was the assistant Scoutmaster. Those were the days when Patrick Sr. never missed a Little League game, and bought Patrick Jr. the BMX bike he wanted. Or the time that Patrick Sr. won Nevada, their Siberian husky, in a raffle. “See how lucky we are?” his father had said, handing Patrick Jr. a dog that became his constant companion. As a teenager, Patrick Jr. discovered the perks of his father’s profession. He met Korn, kicked it with John Leguizamo, was sassed by Joan Rivers, and got VIP tickets to the Warped tour. Sometimes, in the Cessna, his father would let him take the controls when they were flying past the Statue of Liberty.

What had happened since? Like many addiction chronicles, Patrick Jr.’s was a familiar tale — and its own tragedy. His parents’ divorce was acrimonious. When his mother disappeared into drugs, in and out of jail and sober houses, it was hard for Patrick Jr.; when she was around, it wasn’t any easier. Bouncing between suburban life and a drug den created a kind of emotional whiplash. By eighth grade, Patrick Jr. was smoking weed and staying out late. At parties, he drank more than everyone else and would try any drug on offer. His relationship with his father disintegrated. He was sent to a Catholic school; to a “freethinking” school; and to a military academy, where he did well academically but could not kick addiction. He progressed from chasing booze with Vicodin for the hangovers, to OxyContin, to blues and roxies, and finally to heroin.

That was the story, but Patrick Jr. didn’t like to talk about it much, certainly not with his father. After the overdose in November of 2011, Patrick Sr. visited him in rehab, and they kept the conversation light. It was Thanksgiving Day. They ate turkey, tried to make the best of it. Patrick Jr. was in a bit of a daze, probably from the detox medications. But how much was there to say? Both of them knew he was not interested in sobriety. When his days were done, Patrick Jr. checked himself out and wandered off into the night.

Eventually, he showed up at the apartment of his sometimes girlfriend, Rachel. They’d met working at a restaurant called Sushi Lounge and, after a rocky introduction, fell hard for each other. They were an unlikely couple. Rachel was disciplined and practical, but she liked how Patrick Jr. was easy to talk to, a sensitive person, a real person, unlike the standard-fare fraternity guys she’d met in college. But she could not abide his drug use. Rachel’s sole house rule was for Patrick Jr. to stay clean. So when she came home from work one day to find Patrick Jr. on the couch, high as ever, she asked him to leave. He protested that he had nowhere to go. Characteristically direct, Rachel said: “That’s not my problem.”

This is how Patrick Jr. found his way to the Occupy Newark camp, where, a few weeks later, on December 15, 2011, his phone buzzed. It was his father.

“Are you interested in going to Angola?”

“What the fuck are you talking about?”

Patrick Sr. had realized that the only way he could secure the deal with Riquinho and Nas was to send an advance man to cover logistics — and, most important, serve as the fee guarantee. The best person he could think of was his son. Patrick Sr. gave him the rundown: Patrick Jr. would go to Angola and make arrangements. Riquinho would wire the money. Nas would get his fee. Patrick Sr. would join for the concert, and they’d both fly back in the chips.

“So you want me to be the collateral?” Patrick Jr. said.

“Well, if you want to put it that way,” Patrick Sr. said.

Patrick Jr. was not exactly surprised — his father was always into some wild new scheme. Patrick Sr. assured him it was just like all the other international shows he’d done before, just a little more complicated.

“You’re out of your mind,” Patrick Jr. said.

Patrick Sr. spun a bigger story about how this gig was going to change everything for the Allocco family. Patrick Jr. could detox on the trip. They would both get back on their feet, and when they returned from Angola, Patrick Sr. would pay Junior’s rent for a year to get him off the street. It would be a fresh start.

“You’re still out of your mind,” Patrick Jr. said and hung up.

A few days later, Patrick Sr. sent his son a picture of a fancy hotel with an illuminated pool and cabanas fringed by palms. He didn’t tell him that it was just a random image he’d found on the internet. “It will be like a vacation!” he texted.

“Fuck off,” Patrick Jr. texted back.

Patrick Sr. persisted. In his mind, it made perfect sense. His son had worked for him before. He knew the ropes. The show would need an advance man anyhow. And Patrick Sr. really did figure the kid could sober up along the way. “It’ll be like emergency rehab,” Patrick Sr. told Abby. “Maybe this is just what Patrick Jr. needs.” When she said it might not be safe, he said, “The drug dealers of Newark aren’t safe!”

For a week, Patrick Jr. remained unconvinced. He was on probation, for one thing, and wasn’t supposed to leave the state. When his dad called, Patrick Jr. would say he was happy with his tent and his drugs. He was also hoping to patch things up with Rachel, although it was tough going. One night, when Patrick Jr. was extremely high, she stopped answering his calls. He left the Newark camp on foot, forged through the cold, and showed up at her apartment, strung out and in slippers because his feet were so swollen he couldn’t wear his shoes.

When he got to Rachel’s door, Patrick Jr. saw that another man was there. “Why the fuck is this guy here?” he demanded and burst inside. The heroin had withered Patrick Jr. from 200 to 150 pounds, but that didn’t stop him from taking a swing.

“What are you doing?!” Rachel yelled, getting between them. The guy was just a friend. He was there consoling her, she said, “because of you.”

Patrick Jr. stopped his brawl. You never know which bottom is rock bottom, but this felt like a good candidate. “You need to figure your shit out,” Rachel said. She and the friend got in the car and fled her own apartment. His grand gesture had only pushed Rachel further away. Patrick Jr. watched her taillights disappear into the night. And that’s when he called his father. “All right, Dad,” he said, standing outside in his slippers, his breath visible in the cold. “Let’s go to Angola.”

Chapter 3

Patrick Jr. touched down at Quatro de Fevereiro International Airport in Luanda on December 27. He’d never before descended stairs from a plane onto the tarmac, as in the old movies. He watched the heat waves and their tiny mirages rise from the weathered airstrip, and in the distance, he was delighted to see a giant baobab tree, just like on the Discovery Channel.

It had been a rough trip. Patrick Jr. had managed to get a doctor to give him some Suboxone pills, but he did not have quite enough, so he was spacing them out and was beset by constant, low-grade withdrawal. There had been only a few days to get ready in New Jersey. While running errands with his father, they’d had lunch at Friendly’s, where Patrick Jr.’s chicken-tender sandwich became his own deep-fried bite into the madeleine, conjuring a cascade of memories: hot dogs with his grandfather after football games; summer ice cream with his skateboarding pals; and, later, getting fired from the restaurant as a waiter — twice. (Once for being so strung out he visibly sweated into a patron’s chicken noodle soup.) The following morning, Patrick Sr. gave him a wad of cash, put him on a 5:30 a.m. train to an expedited passport service in the city, and told him: “Do not get high.” Patrick Jr. didn’t. It felt peculiar, going from homeless to carrying a briefcase with passport paperwork to Manhattan, like he was an impostor. Later that day, Patrick Jr. counted out his Suboxone supply against the number of days he planned to be in Angola and grimaced.

His flight to Luanda quickly went wrong. A layover in Lisbon turned into a four-day wait to sort out his travel documents; the officials there said that the visas supplied by Riquinho were incomplete. Waiting for the paperwork to clear, Patrick Jr. spent Christmas in Lisbon by himself and kind of enjoyed it. He had a sweet hotel room and was tickled to discover the strange indulgence of the bidet. He went for a walk and gave a panhandler €10. He took himself out for a solo, but pleasant, Christmas dinner, but he threw it all up later.

Whatever the hitch was with Patrick Jr.’s visa, it was undone when Riquinho got on the phone from Angola with the Portuguese immigration officials and the airline’s local manager and yelled for ten minutes straight. After that, they let Patrick Jr. on the next plane to Luanda. Before he boarded, the airline officials warned him that whatever happened with local authorities would be his responsibility. Fly at your own peril, they said.

Immediately upon arrival in Angola, Patrick Jr. was pulled out of the immigration line and ordered to wait. When he’d asked his probation officer for permission to travel, he’d told the guy he was just going to Disney World, and now here he was in Angola, already sweating from head to toe. He called his father, anxious. “Just sit tight,” Patrick Sr. said. “I’m sure it will be fine.”

To his relief, Patrick Jr. was cleared at the Angolan immigration desk after an hour. It did seem strange that the officials kept his passport, but he made no protest. He was collected by one of Riquinho’s associates, Zeca, who walked right through a security checkpoint and cracked a beer at the pickup curb as they drove away.

Zeca was a jolly middle-aged guy who took to Patrick Jr. right away, and as they drove, he pointed things out around the city. It was Patrick Jr.’s first glimpse of Luanda and the gritty reality of an overpopulated capital in a developing country. Many roads were barely passable, and traffic was chaotic, a cacophony of horns and trucks trailing black smoke. There were women and children peddling boiled eggs and fruit. Patrick Jr. had never seen an entire neighborhood made largely of corrugated tin or people living in landfills. He’d been homeless in New Jersey, but he’d never seen true poverty.

“Now we are coming to the city center,” Zeca said. Patrick Jr. saw a different Luanda rise up around him. Soaring overhead were glass skyscrapers and cranes building more skyscrapers, a glittering business district along Luanda Bay, brimming with Range Rovers, Hummers, and Porsche Cayennes. He couldn’t make sense of it. The city seemed like a peculiar mix of Miami and a UNICEF commercial.

Which, to some degree, it was. Even to experienced travelers, Luanda can be a perplexing place. The deep poverty and extreme wealth on display, often within a few blocks, is like few other places in the world. Patrick Jr. had no idea that the airport he came through that morning was named the 4th of February after the start of the war that freed Angola from the degradations of colonial rule. Final independence from Lisbon was won in 1975. When the Portuguese evacuated, they packed up as much of the city as they could and took it with them, leaving almost no commerce, trade, or training. It had been almost four hundred years since the city was founded as a slave port.

“After independence,” Zeca said, “we had a long civil war.” Patrick Jr. asked what it was about, and Zeca said it was complicated. For 27 years, the conflict was a proxy Cold War battlefield — well funded and highly destructive. Any infrastructure the Portuguese hadn’t shipped to Lisbon was annihilated. The country’s oil and diamond resources only made it worse. (As an example of the tortured allegiances of business and politics, the leader of the doctrinaire Marxist faction was a Soviet client, backed by Cuban troops — all paid for by Chevron.) More than a million people died.

Now, Zeca said, business was booming and he was excited about the future. When the war ended, foreign investment arrived, and the economy — built almost entirely around oil and minerals — grew tenfold in ten years. Zeca said that Angola was becoming more cosmopolitan. “We have more visitors,” he said. “And more money.” Luanda was indeed awash in money, although almost all of it was concentrated in a tiny elite, at the center of which was the ruling dos Santos family, which had long ago abandoned Marxism to preside over a kleptocratic regime. They became billionaires while more than half of Luanda’s residents had no potable water and lived on less than $2 a day.

And yet Luanda was simultaneously one of the world’s most expensive cities. A wildly overpriced import economy arose around the rich oil-services executives who travel there or live in guarded neighborhoods like Bella Vista and Paraíso Riviera. Zeca pointed out the high walls of some of those expat citadels. In the stores servicing those residents, a bottle of water could go for $10; ice cream, $25; one supermarket gained notoriety for selling melons at $105 apiece. Along Avenida de Portugal, the city’s equivalent of Rodeo Drive, the hotels started at $400 a night.

Zeca dropped Patrick Jr. off at the Hotel Alvalade, a tan tower in an old colonial neighborhood now full of Luanda’s nouveau riche. The lobby doors were guarded by men with machine guns. On the roof was a pool with a view of the emerging city skyline. Beyond that was the port, full of ships heavy with crude, and the Ilha do Cabo, a long, thin island that encloses the bay and hosts a strip of sandy beaches and nightclubs. Patrick Jr. could feel the creep of withdrawal and had no idea what to expect next. When Zeca left him in the lobby, he told him only to wait for Riquinho’s call.

Chapter 4

Patrick Jr. had just a backpack with some Dickies shorts, a couple shirts, and a carton of Marlboro Reds from the Newark duty free. He was disoriented but excited to be helping his father again. When he was stuck in Lisbon, his father said he could come home if he felt too sick or apprehensive, but Patrick Jr. declined. “I made it this far,” he said. “I’m going to see this through.”

Patrick Jr. wanted to get this right. There were, in fact, critical logistics to arrange. And he was a Nas fan — as a kid, he’d listen to “N.Y. State of Mind” on headphones while riding the BMX bike his father had bought him. Now he had to procure visas for Nas and his entourage and get him onstage at a giant arena. After the show, Patrick Jr. thought, maybe we’ll smoke a blunt together. That would be pretty cool.

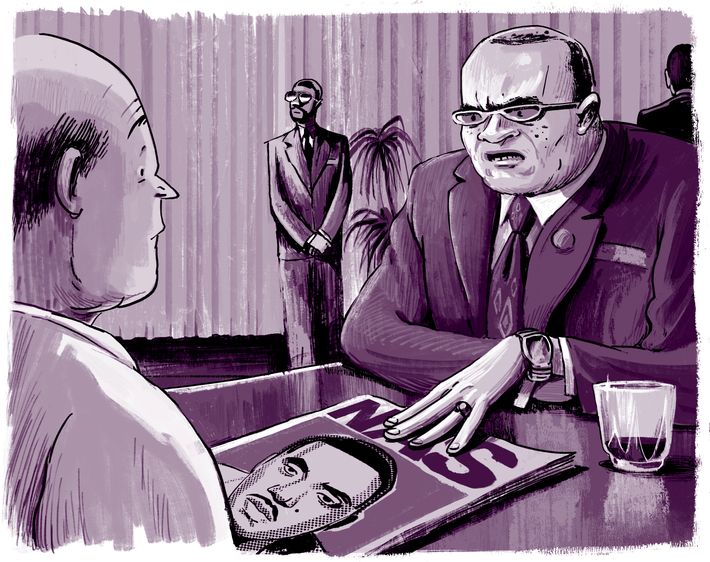

After a few hours, the call came: Patrick Jr. was instructed to meet Riquinho in the hotel restaurant. He was not expecting a man as formal, serious, and physically imposing as Riquinho. He was six-foot-four and wore a striking tailored suit. Patrick Jr. was in his Dickies and a wrinkled shirt he’d had since eighth grade. When he shook Riquinho’s hand, it felt like he was greeting a baseball catcher.

“Is Nas coming?” Riquinho asked.

“Yes,” Patrick Jr. said. “We just have to get the travel documents and tickets in order and wire the money.”

A Lincoln Navigator with chrome rims awaited them. Inside, the leather was spotless. Sitting next to Riquinho, Patrick Jr. felt ridiculous in his hobo attire. He folded his arms to hide his track marks. Riquinho spoke basic English, and Patrick Jr. tried to answer in Spanish, figuring it might overlap with Portuguese — a futile effort. At one point, Riquinho gestured at the city like it was his dominion. “Any girl you want,” he said. “You pick one.” Patrick Jr. demurred.

They arrived at a cell-phone store that Riquinho seemed to own. When he entered, the men inside shot to attention. Riquinho carried an expandable leather suitcase, and he opened it to reveal thick bricks of kwanza, the local currency, which he started to casually hand to his men. People came and went, paying respects, taking orders and cash from Riquinho, who seemed to be making a demonstration for Patrick Jr.

It worked. He was impressed and unnerved. The next stop was Riquinho’s office, where there was a big desk and pictures of the man shaking hands with President José Eduardo dos Santos. They sat beneath a large Angolan flag — a striking take on Soviet iconography with a machete instead of a hammer — and discussed plans for the concerts. Out front, Patrick Jr. smoked a cigarette with one of Riquinho’s men who spoke English. “Riquinho can get anything in this town,” the man said. “He’s as powerful as the president.” As they left, another man handed Patrick Jr. a flip phone and said, “This is how we will reach you.”

The next few days were a blur of heat, confusion, and nausea as Patrick Jr. accompanied Riquinho on time-sensitive errands. They went to the concert venues, and he saw the stadium where Nas would entertain a teeming New Year’s Eve crowd. Riquinho assembled what he said was the travel paperwork for Nas and his entourage. They carried around duffel bags full of cash. Some of it they brought to a Lufthansa office to buy the plane tickets, a process that somehow took seven hours. A lot more of it went to the Banco de Poupança e Crédito for the wire transfers to Patrick Sr.’s account. The bank manager greeted Riquinho with great zeal, then looked at Patrick Jr., standing there in his skateboarding shirt, with confusion. Then they wired nearly half a million dollars to New Jersey.

Back at the hotel, Patrick Jr. felt like he was being watched. He often caught the hotel staff staring. There always seemed to be someone nearby, cleaning windows or polishing floors, for hours on end. Riquinho probably had eyes all over, he thought. Before he left for Angola, Patrick Jr. and his father joked that he would make a great “professional hostage,” but now that seemed a lot less funny.

He was thousands of miles from home, in business with a man he and his father knew nothing about. He’d been excited at the thought of helping save the family business, but now he worried he’d fallen for one of his father’s schemes. Hopefully, Patrick Sr.’s grand plan would come together. He’d be arriving soon, then it would all work out, right? Patrick Jr. counted his Suboxone tabs again. It had been quite some time since he genuinely looked forward to seeing his father.

Patrick Sr. wandered around a survivalist supply depot in New Jersey called Get Out Safe, gearing up. He’d never been to Angola and didn’t know what to expect. Preparation time was short, and he figured it couldn’t hurt to get provisioned as a precaution; he stocked up on basics, including a first-aid kit, MREs, and a box of Mayday-brand emergency drinking water. Walking back to his car, Patrick Sr. passed by the sign out front that said: DON’T WAIT UNTIL IT’S TOO LATE.

It was December 28 — Patrick Sr.’s birthday. The concert was just a couple days away, and the deal was still precarious. From Luanda, Patrick Jr. kept calling with updates, positive but apprehensive. Patrick Sr. consulted his checklist and drove his ancient Volvo station wagon around New Jersey in a state of giddy anxiety.

His contacts in the music business remained skeptical. There were horror stories about Riquinho, they said — about performers like Ja Rule, Fat Joe, and DMX being prevented from leaving the country and forced to play additional shows. (Ja Rule later characterized what transpired as a kind of “good kidnapping.” DMX put it more plainly in 2015: “He tried to kidnap us.” Dame Grease, one of his producers, said, “That was the first time that I realized that I’m an American.” Riquinho disputes these accounts.) “I don’t know about this,” one former partner said. “This guy is dangerous.”

But when the moment requires, Patrick Sr. can be very convincing. He had certainly convinced himself: The deal may have seemed like a tightrope walk with no net, but as he described it to Abby, it was in fact a clever transactional foothold on a whole new business. If it went well, he could do more business with Riquinho. Sure, he’d heard those stories about supposed kidnappings, but that’s only what happened when something went wrong. His optimism seemed warranted when the first wire payment came through the next day. There it was: $400,000.

After enlisting a former partner to help with logistics in the U.S., Patrick Sr. took 20 minutes to pack a duffel bag with some clothes and his survivalist larder, arranged to get the money to Nas’s manager, and headed for the airport. He didn’t have time to worry about the jittery emails he got from Nas’s manager about travel documentation, safe transportation, and the one that said: “If for any reason Nas doesn’t board the flight … we will get that money right back to you.” Why would they not board the flight?

Besides, it was too late to back out now. It felt like the Election Nights when he worked for political campaigns: As results came in, you didn’t know the outcome, so you ran your checklist, held everyone’s hand, and hoped for the best. Every promotion is a frenzy — until it works out. Or doesn’t. Patrick Sr. had delivered big, successful shows in the Caribbean. He’d also had his entire box office stolen in Mexico.

He’d never been superstitious about a gig before or had premonitions, but sitting on the plane, he found himself uneasy. People he knew had done plenty of shows in Angola. Ludacris had just played there, and it went fine. Usually, though, Patrick Sr. would have had the act sitting right next to him. In the rush, there had been no time to arrange that. Somewhere, hopefully, Nas was about to walk down another jetway, get on some other plane, and make everyone good money.

Chapter 5

The next morning, Patrick Sr. changed planes, and soon the captain announced they were flying over the Sahara. Patrick Sr. thought about all that sand below, a single desert the size of the entire United States. He recalled his pitch to Abby about how Africa was a neglected market. He still loved this business because he believed in the power of music, and Live Nation certainly wasn’t paying attention to the audiences here. He could bring a whole tour on four or five dates, run a circuit, start in Johannesburg and end in Ghana. It really could all be the start of something new.

When Patrick Sr. arrived at Quatro De Fevereiro, his first few minutes in the country were just like his son’s. He was forced to wait, and his passport was confiscated. On the other side of security, Patrick Jr. was waiting. Patrick Sr. was proud of his son, how he’d handled the work in Angola well. But when they hugged, Patrick Jr. whispered in father’s ear so no one could hear: “There’s a problem.”

Very funny, Patrick said. “No,” his son said. “I’m serious. Nas did not board the flight. No one is coming. We are fucked.” Patrick Sr. stopped smiling.

As they left the airport, Patrick Jr. discreetly disclosed the alarming news of the past few hours. He’d arranged everything as requested, and Nas’s manager had confirmed that his crew had boarding passes — he’d even sent a picture — but shortly thereafter the manager said the travel documents looked sketchy and the wire had been late, so the whole thing felt slapdash. The particulars didn’t really matter, because the reality was that Nas was not in Angola and the concert was meant to start in 24 hours.

At first, Patrick Sr. thought it could somehow be fixed. He got on the phone with Nas’s manager and other intermediaries, trying to sort through it all, still imagining he could perform some kind of miracle and save the show. But at a certain point, the clock was against them. Even if Nas agreed, there was not enough time for anyone to fly to Angola. When Patrick Sr. took a deep breath and tried to explain to Riquinho that, well, there just might be a little complication with the concert, it didn’t go well. “No!” Riquinho yelled, so loud that Patrick Sr. held the phone away from his ear. “Musicians must come!”

Now, all those stories about Riquinho could not be waved off. In addition to being known for the incidents with DMX, Ja Rule, and Fat Joe, Riquinho was said to have threatened promoters. David Osborn, a promoter who’d done a lot of business with Riquinho, said it was not for the faint of heart. Osborn’s first hip-hop concert in Angola was Sisqo, and Riquinho told him that if the man behind “The Thong Song” did not appear, he would shoot Osborn in the head. Sisqo played, everyone got paid, and Osborn kept coming back because he spoke Portuguese and the money was great.

Eventually, one deal did go sour. Osborn says he was pulled out of his hotel room by Riquinho’s people, put in a windowless van, tied to a chair, and beaten so badly that some of his teeth were knocked out. (Riquinho disputes this account.) This was among the reasons that when Patrick Sr. told Osborn he had managed to orchestrate this New Year’s with Nas, Osborn said, “I would stay home and watch the ball drop.”

It was a little past 3 a.m. when the inescapable reality of their situation dawned on Patrick Sr. They were at Patrick Jr.’s hotel, which still felt full of spies. Patrick Sr. called the U.S. Embassy’s emergency number and eventually reached David Josar, a consular officer who worked in American Citizen Services. “My son and I have no passports,” he said. “We are in danger.” Angola doesn’t get many American tourists — almost all visitors work in oil or mining — so it was not common to get distress calls in the middle of the night. But Josar understood: The State Department had warned music promoters that working in Angola was unsafe. Patrick Sr. had not seen it. (“Who ever reads the travel advisories?” he later said.)

The embassy was closed for the holidays, but Josar said it would make an exception and open for this emergency. He told the Alloccos to be at the embassy, bags packed, at 9 a.m. They waited for daybreak, hired a driver, and were soon heading through the streets of Luanda. Patrick Jr. was shuddering with withdrawal. But he was alert enough to notice that they were in the same neighborhood where he’d visited Riquinho’s office and watched him hand out stacks of cash to henchmen. Then, without warning, the driver pulled over, got out of the car, and walked away. “You stay here,” he said.

By now it was clear they were not going to the embassy. Patrick Jr. was right; Riquinho did have spies at the hotel, and the receptionist had delayed their taxi and tipped off Riquinho. The driver had delivered the Alloccos right to him. “This is his turf,” Patrick Jr. said to his father. “We gotta run for it.”