The Whitney Biennial isn’t what it used to be. Once, it was mainly for the inhabitants of that strange royal court we call the art world — for insiders, in other words. The past several Whitney Biennials have turned the tables. It is no longer a gathering of warring, incestuous tribes of gallerists and curators and hangers-on but an outward-facing event for everyone interested in art and culture and the issues that face humanity as a whole. The show isn’t for people like me; it’s for the public. These are the exhibition’s contemporary values — for better and worse.

Underscoring the point is this Biennial’s title, “Even Better Than the Real Thing.” Named for a U2 song from 1991, it is a show gesturing at artificial intelligence that actually has very few works dealing with that hot topic. The show does address Gaza, climate change, abortion, and the continued effects of the pandemic. Every work gets ample room to do whatever it purports to be doing, but as a result, there’s little optical pop or psychological nerve, as if a maximum of effort had been deployed for minimum effect. Nearly half of the 71 artists live or were born outside the U.S., yet all this diversity has somehow produced an underlying aesthetic that is familiar, predictable, and very safe.

As well made and well meaning as the art is, most of what you see could have been made in the 1970s, 1980s, or 1990s; the forms and styles are old. Only the subject matter is new. Almost despite itself, the Biennial also features excellent work that conveys new meaning to the world, at least partly justifying the recent impulse to be less insular and academic. In all these ways, the Biennial is an agenda-driven snapshot of what art is today — the good, the bad, and the very bad.

Mavis Pusey’s riveting geometric paintings, made in the 1960s and ’70s, instantly make you wince when you consider that this deceased Jamaican-born artist was unjustly passed over in her life.

Don’t miss Suzanne Jackson’s amazing hanging encrustations of poured and scraped paint. These things are so morphologically alive they become skin.

A wall by Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio made of amber and embedded with dirt, detritus, and archival material from white activist groups. It pulses darkly with life, melting very slowly in the sunlight from the nearby windows.

A lot of art here just takes up space. P. Staff’s all-yellow room with an electrified net suspended overhead is a good place to take a selfie.

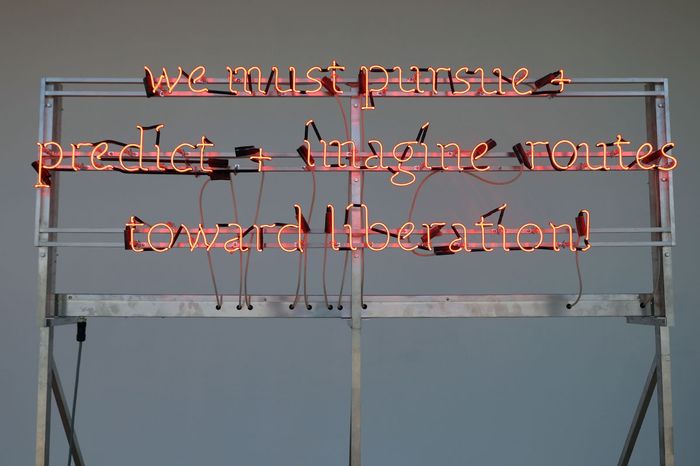

A neon text by Demian DinéYazhi’ reads, WE MUST PURSUE + PREDICT + IMAGINE ROUTES TOWARD LIBERATION. It’s great to include this artist. But not this simplistic meme.

Skip the dead, shiny AI images of Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, who, despite occupying the 77th spot on ArtReview’s insane “Power 100” list, are pretty horrendous stand-ins here for better digital artists.

There’s a lot of bad art made in obvious ways. The sculptures of fishing detritus by Karyn Oliver, composed of buoys, rope, fabric, lobster traps, and driftwood, trade in a well-worn aesthetic. The wall text states that the work invokes “the practice of trading salt for enslaved people in ancient Greece.”

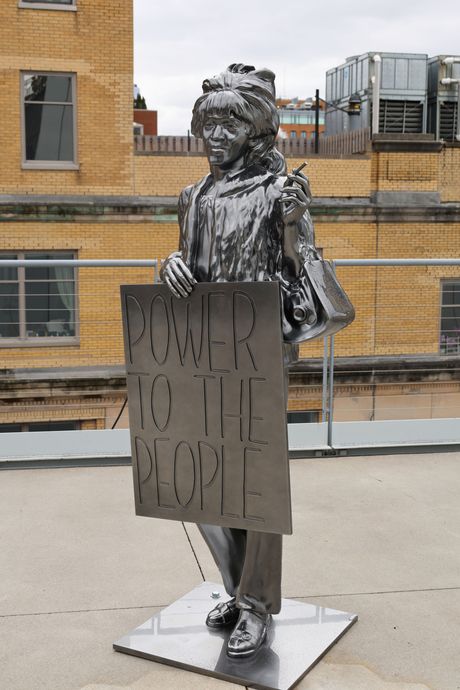

Kiyan Williams’s sculpture of the trans activist Marsha P. Johnson standing “as a witness” is a self-indulgent piece that says nothing about America on

the precipice.

Ser Serpas’s lobby installation features a ratty section of a couch with a soiled American flag. This is the Biennial at its best: beautiful, serious, experimental chaos.

Top photo grid: Suzanne Jackson, Rag-to-Wobble, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Ortuzar Projects, New York. Photograph by David Kaminsky.Isaac Julien, Iolaus/In the Life (Once Again… Statues Never Die), 2022. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London.Torkwase Dyson, Liquid Shadows, Solid Dreams (A Monastic Playground), 2024. Photograph by Audrey Wang.Harmony Hammond, Black Cross II, 2020–21. Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York. Photograph by Eric Swanson.Demian DinéYazhi’, we must stop imaging apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation, 2024. Photograph by Nora Gomez-Strauss.Rose B. Simpson, Daughters: Reverence (Daughters 1, 2, 3), 2023. Photograph by Audrey Wang.Ser Serpas, taken through back entrances subtle fate matching matte thing soiled…, 2024. Photograph by Audrey WangP. Staff, Afferent Nerves and A Travers Le Mal, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Kunsthalle Basel. Photograph by Philipp Hänger.Eamon Ore-Giron, Talking Shit with Viracocha’s Rainbow (Iteration I), 2023. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photograph by Charles White.Charisse Pearlina Weston, un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), 2024. Photograph by Nora Gomez-Strauss.Mavis Pusey, Within Manhattan, 1977. Photograph by Elon Schoenholz.B. Ingrid Olson, Completed Movement (between abut and rub between two notes the number between one and two divided into qualities and kinds), 2016–22. Photograph by Robert Chase Heishan.Takako Yamaguchi, Issue, 2023. Courtesy Ortuzar Projects, New York.Photograph by Gene Ogami.Kiyan Williams, Statue of Freedom (Marsha P. Johnson), 2024. Photograph by Audrey Wang.Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio, Paloma Blanca Deja Volar/White Dove Let Us Fly, 2024. Photograph by Nora Gomez-Strauss.Seba Calfuqueo, still from TRAY TRAY KO, 2022. Courtesy the artist. Photograph by Sebastian Melo.Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst, xhairymutantx Embedding Study 1, 2024. Photograph by Audrey Wang.Karyn Olivier, How Many Ways Can You Disappear, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los Angeles. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.Jes Fan, Cross Section (Right Leg Muscle II), 2023. Courtesy the artist; Empty Gallery, Hong Kong; and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. Photograph by Olympia Shannon.

More Art News

- How Jonathan Franzen Learned to Write a Franzen Novel

- It’s One Banana, Michael. What Could It Cost? $6.2 Million?

- The Extremely Chaotic Life of Jamian Juliano-Villani