This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Considering the meta nature of Taylor Swift’s performances — her autobiographical lyrics and her intimate connection with audiences — it’s unsurprising that her fashion choices betray self-consciousness. One senses that she isn’t entirely comfortable with high fashion, and maybe that’s something she shares with her young fans and why they instinctively relate to her. Swift is 34 and one of the most successful musical artists in history, with an empire estimated at over $1 billion. And much of that success is due to the image she projects — of a woman still coming of age, still discovering herself. Any style that’s too sophisticated or eccentric would spoil the illusion, and that goes for her red-carpet and casual attire as well as her stage clothes.

For the Eras tour, which had 16 costumes per show, Swift did have some looks by Versace, Oscar de la Renta, and Roberto Cavalli. But these are not the most exciting designer names. Besides, the Cavalli and Versace styles — a beaded miniskirt and cropped top or a bejeweled bodysuit, all worn with glitter boots — conformed to Swift’s favorite stage aesthetic of a drum majorette. She dressed like a marching-band leader, in a gold-braided white jacket and top hat, for her 2009 global Fearless tour. To me, so many of her costumes are reminiscent of the corny saloon-gal styles that another American sweetheart, Debbie Reynolds, wore in westerns, as well as the spangled costumes that the great Bob Mackie designed for TV variety shows in the 1960s and ’70s. There’s a wonderful hoofer charm, a showgirl moxie, about these Swift looks that resonate with audiences. During Eras, Swift also wore ethereal princess gowns — another key style for the singer — like a dreamy Elie Saab number in blush tulle and a lavender tiered Nicole + Felicia dress, both worn for the Speak Now section.

By contrast, other pop divas have harnessed high fashion to their power. Look at Madonna’s “Blond Ambition” phase, in 1990, and her use of Jean Paul Gaultier’s shocking designs. Beyoncé, for her Renaissance tour, completely bent fashion to her will, taking the work of some of the most daring designers — Marc Jacobs, Rick Owens, and Jonathan Anderson of Loewe, to name three — and pushing their looks for her further into fantasy.

That’s not Swift’s jam or, rather, her brand. She sees herself as a storyteller, in the tradition of Joni Mitchell. She has sung about love, breakups, revenge, family, and self-loathing. These are universal themes and especially relevant to girls and young women. Swift is famous for planting what she calls “Easter eggs” — hidden clues — in her lyrics. Describing the strategy as a way to “incentivize” fans to read her lyrics, she has said, “I think the best messages are cryptic ones.” This also applies to her style. Indeed, with Swift — more than most pop stars — every choice seems to relate to her work or the Swift brand image. One obvious, feel-good connection point with her audience — which includes moms who accompany their daughters to concerts — is nostalgia and a feeling of pageantry. Some of her frothy gowns evoke not only high-school prom and images of old-style debutante parties but also the glamour of Edith Head’s movie costumes in the 1950s. Swift has said that watching Hitchcock’s Rear Window — gowns by Head — and reading the romantic novel Rebecca during lockdown influenced her albums Folklore and Evermore. In a cynical, fast-moving world, that kind of traditional form can seem quite attractive.

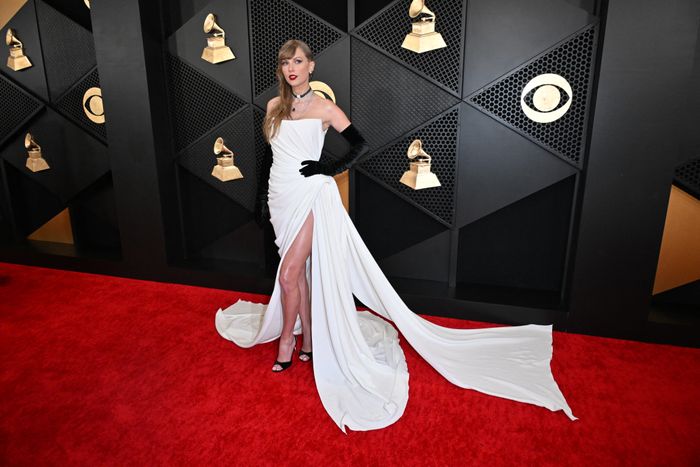

It’s also worth noting that Swift is hyperaware of the dangers of celebrity. “I see a lot of celebrities build up these emotional walls around themselves where they let no one in,” she said in 2014, “and that’s what makes them feel very lonely at the top.” Staying emotionally open in her lyrics and accessible in her fashion is surely a way she avoids creating walls. Her fans must sense that. But it can lead to some self-conscious looks on the red carpet and in her street attire. This was true of the white custom-made Schiaparelli gown with a floor-sweeping hem and train that she wore to this year’s Grammys, which was criticized across social media. On Instagram, Sarah Chapelle (@taylorswiftstyled), who is publishing a book this fall about Swift’s style, likened the gown’s draping to “tangled bedsheets” and said that considering it was the work of Daniel Roseberry, it was “almost a greater disappointment.” Chapelle, who has spent years tracking and decoding every detail of Swift’s outfits, assumed that the gown and its black accessories were Easter eggs. This time, the hint was to her forthcoming album The Tortured Poets Department, which has a black-and-white cover of a woman in black underwear lying in white sheets. Chapelle hunted down the make of the undies — a sheer Saint Laurent top and The Row’s briefs — and noted that Swift’s wearing so much of late from those brands was no coincidence. “Is there ever one with Taylor, really?” wrote Chapelle. She felt that the beautiful elements of the Schiaparelli gown were “sacrificed to the early evocation of a scholarly-sounding album.”

In other words, Swift laid a bad egg.

There is also a fair amount of calculation in the singer’s off-duty clothes — more than a non-Swifty might suppose, given how basic much of her street style is. Her favorite looks, and maybe her best, are easy slip dresses, or a frilly white shirt with denim cutoffs and boots, or a schoolgirl plaid skirt with a plain sweater and chunky loafers — what one Swiftologist calls “liberal arts student, Shoreditch dweller.” Though Swift is known for wearing relatively inexpensive brands like Rails, House of CB (for a $119 black bustier top she wore earlier this year with a $1,400 Miu Miu mini), Madewell and Reformation, she also wears a lot of high-end labels, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci, The Row, Stella McCartney, and Area. Lots of celebrities play with a similar high-low mix, but with Swift, the effect generally comes off as decidedly junior, as though she’s consciously trying not to get above her fans’ tastes or means.

As a Kansas City Chiefs fan, I watched Swift’s appearances during the NFL season to cheer on her boyfriend, Travis Kelce. Still, I found nothing special about her red sweaters and bombers, with layers of gold jewelry, other than a tie-in to K.C.’s team color. But Chapelle found the Easter eggs. The red crewneck, from Gigi Hadid’s Guest in Residence brand, that Swift wore to the Chiefs’ title match with the Ravens was a “sentimental” nod to a friend. In Chapelle’s view, its plainness showed that Swift was careful “to strike a more supportive spectator (not starring) role” at such a big game. Chapelle clocked her diamond tennis bracelet with the romantic letters “TNT” and then linked the style to the friendship bracelets her fans wear, a fad that started because of a line in a song she wrote.

The fact that Swift makes all these gestures, with or without the help of a stylist (she has long worked with Joseph Cassell), is a great way to keep her fans engaged. And apparently, it’s also good for business. But it seems exhausting and limiting for a woman in her mid-30s to dress according to a lyric or a girlish sentiment. You can understand why many people on fan sites wish she’d take more risks with her street style. They’re probably bored with the “liberal arts student” look. It’s also a little disingenuous, given her grown-up status. I admire the fact that she doesn’t seem interested in playing the high-fashion game — that is, turning up at the shows or appearing in a campaign or being a brand ambassador. She has her own immense platform, which she’s used for political and social causes.

But she could afford to go further in her style. Instead of a schoolgirl skirt or a baggy pair of jeans, she’d look amazing in, say, a sleek Dior pencil suit, made to measure — why not? — and without all the trinket jewelry, however expensive. It’s worth remembering that Taylor Swift has always been older and wiser than her years. The girl can’t be discovering herself forever.