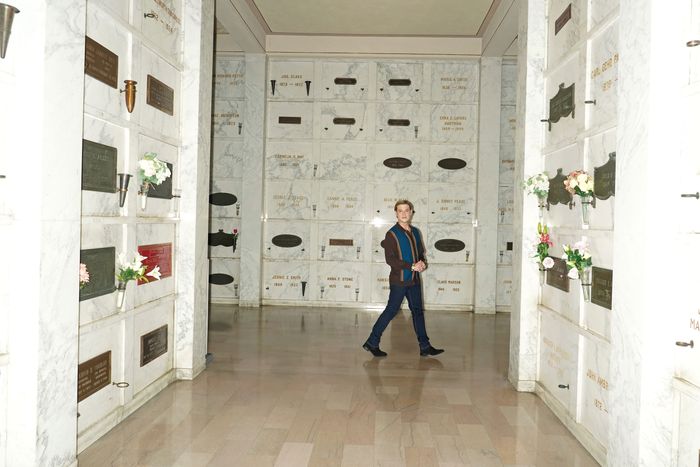

It’s a chilly, overcast day, and fog wreaths the monuments at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles, driving away all but the most determined tourists. Still, little groups of people in twos and threes are making their way among the gravestones and mausoleums, taking note of the movie stars and very rich people buried here, and all of them — literally all of them — interrupt Tyler Henry’s photo shoot to politely ask him for a selfie.

I assumed he would have some celebrity sightings of his own (what I wouldn’t give to hear from Judy Garland, who’s laid to rest right nearby). After all, the 28-year-old Henry is one of the most famous psychic mediums alive, with three TV series under his belt, a long list of celebrity clients (a handful of Kardashians, RuPaul, and Allison Janney, to name a few), and a 700,000-person waiting list for readings. But for Henry, cemeteries are dead silent; spirits only come to him via their living relatives, he tells me in a secluded corner of the Cathedral Mausoleum as he sips one of the six venti iced lattes he drinks every day. But when he does, as he puts it, “open those floodgates” during a reading, “you never know what’s going to come out.”

Every Tuesday, on his new Netflix show Live From the Other Side, he sits down with a celebrity and performs his trademark reading, holding objects that belonged to deceased loved ones his guests are hoping will “come through,” scribbling in his notebook as he focuses on their energies, and listening for their voices. In spite of being about ceasing to corporeally exist, Henry’s shows are somehow as cozy and upbeat and backgroundish as HGTV.

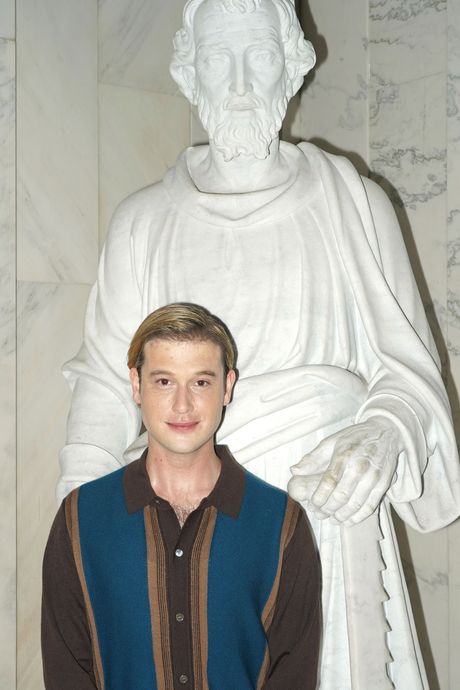

The key to the winning formula is Henry’s oddball charisma. He still looks almost exactly as youthful as he did when viewers first encountered him nearly a decade ago, with the same floppy blond mop, soulful deep-brown eyes, and easy megawatt grin. He’s here at the cemetery with his mom, Theresa, who drives him everywhere because he never learned (“I feel like if I don’t have to do it, why should I?” he says, not unreasonably). They don’t live together anymore — he moved in with his partner, Clint, four years ago — but she still makes him dinner that they eat together every night, which is often plain pasta with grated cheddar cheese. He can’t really go to the grocery store because there are so many people’s psychic energies swirling around there, and also so many people who want selfies, which is why his assistants or Clint or his mom usually handle the mundane tasks of life, like acquiring those Starbucks iced lattes. He keeps his circle small, and after work, he’s glad to come home to them. “They view me more as a person than a medium.”

Henry’s abilities as a psychic medium started early. At 10, he had a premonition of his grandmother’s death, which was confirmed by a phone call a few minutes later. After that, the communications from the other side came thick and fast, and Henry at first had no idea how to handle them. He would tell kids at school things they didn’t even know about their own families, just because those facts were available to him. His high-school math teacher Trishaa Camp was an early believer in his abilities, after he pulled her aside on the day her mother-in-law died and simply told her, “It’s okay to cry.” It was the first of many unsolicited readings from him. “He’d be like, ‘Hey, your brother’s here.’ I’m like, ‘What?’ He’s like, ‘Your brother’s here. He wants to know how your husband’s doing,’” Camp told me. “I’m like, ‘Tyler, we need to focus.’” And not only was he psychic — he was also gay. It was a lot for a raised-religious kid from an industrial town in California’s San Joaquin Valley. “I grew up in a culture that in many ways did not want me to be myself,” Henry tells me. Henry survived his awkward teen years with help from Camp, who got him on a track to graduate early at 16. He had to make an escape.

Henry began giving readings for $35 in the area’s only occult bookstore, the Cosmic Corral, and word spread. Sarah Paulson wound up hearing about him from some friends who’d gotten a reading from him there, and she called him up to request a session with him that she remembers as “wonderful and sweet.” Their meeting got Henry an invite to a Christmas party in L.A. where he met talent managers Larry Stern and Michael Corbett. The next day, Henry did readings for both of them. Corbett handed Henry a watch, and “it got really real really quick,” Henry says. The watch belonged to a friend who had recently died by suicide, and they came through with specific information about how they passed. “It was pretty shocking,” Corbett told me. “No one knew those details.”

After that, Stern and Corbett rounded up a group of ten friends and shot a sizzle reel of Henry reading them back-to-back over the course of two days in Stern’s backyard. They showed it to the executives at E!, who were into it but wanted to add a celebrity element, and thus Hollywood Medium With Tyler Henry was born. On each episode, Henry would show up to the homes of E!-grade celebrities like Amber Rose, Snooki, and Lil Jon and do readings for them. Occasionally, the cameras captured an honest moment of embarrassment when Henry didn’t recognize the person he was meeting.

After four seasons of reading for celebrities, Henry embarked on his most personal show, Life After Death, in 2022. Slower-paced, with the vibe and music cues of a reality-documentary style show, the series features Henry driving around the U.S. and giving readings to people randomly selected from his waiting list. He also tries to find Theresa’s birth mother, who gave her up for adoption under mysterious circumstances that neither psychic nor traditional research seem fully able to penetrate. Though Henry’s able to discover other people’s secrets, when he tries to read his mom, he comes up empty.

To skeptics who think that assistants or producers must be feeding Henry Googleable information about the people he’s reading beforehand, I can only report that everyone on his team is a true believer. Henry’s worked with the same crew throughout this career: his managers Stern and Corbett, his assistant Heather, his mom, and Clint. Stern became emotional while telling me about how Henry had helped him process loss in his own life, and everyone around him seems almost parentally protective of him. While I was talking to them, and especially while I was talking to Henry, I found myself wholly under his spell.

While watching his shows, though, it can be hard to sustain that kind of wholehearted belief. Though he rarely tells anyone anything they didn’t already know, the drama is in the space between what he professes to know going into the reading — nothing — and what he says when he starts scribbling. “Oh, this is interesting,” he’ll begin, or “Oh, that’s weird.” He might have a physical reaction — a tightness in his chest or difficulty breathing. Soon, we learn how the loved one died — gunshot, drowning, blood clot, mudslide. But lest this cause any distress, Henry reassures his client that the passing was quick, painless, or expected. Now, the loved one is here and happy. So far, any reasonably convincing actor could pull this off, but then comes the unnerving part. “He’s doing a little dance — I can’t do it, I’m a terrible dancer — like this,” Henry tells one grieving mother on Life After Death as he awkwardly wiggles his hips. And it’s exactly the way her son used to dance, and there is simply no way he could have known that. He manages to pull out some intangible detail or gesture like that maybe half the time, but that still seems like a lot. In those moments, I was sold on Henry. But the corny music cues and the insistence that those who have crossed over are full of joy have an oddly flattening effect. Even if Henry’s communications with spirits are 100 percent authentic, there’s something weird about how quickly the show transitions from tragedy to uplift almost instantaneously. It’s almost like it doesn’t give death enough credit.

It’s very rare for the living to hear from Henry that their deceased family members disapprove of any of their decisions, and sometimes spirits have immense changes of heart after passing over. Henry conveyed such a message to Brad Bessey, the director of communications for a food bank that Henry has volunteered with for several years. During her life, Bessey’s mother had strongly disapproved of him being gay and especially didn’t feel comfortable with the fact that he and his husband were adopting a child. She died without changing her mind about the appropriateness of Bessey’s family. But 16 years later, during Henry’s reading, her spirit came through with an entirely different message: one of radical acceptance. Just as he did on the show, Bessey tears up when telling me about it over the phone. “What I needed to hear was a validation that my mom from the other side was checking in, watching, and was proud of the job I was doing as a father,” he says. “That was so moving.”

When comedian Nikki Glaser got the offer to be on Henry’s new show, her management said she didn’t have time in her schedule. She told them to move things around. “I was like, ‘You don’t understand the waiting list!’” Her taping went well, she thought, though there were some moments that didn’t quite land, like when Henry tried to deliver a message intended for her friend to her mother — the spirits had their lines crossed, it seemed. “I walked away from it being like, listen, I can’t say a hundred percent that it’s real. All I know is that if it’s not, I don’t even care,” she says. “Do you know why? If it’s not real, it’s not because Tyler’s doing something to trick us. It’s giving people hope that there’s an afterlife. It’s giving people closure with their loved ones.” Her sister’s now going to get a cancer screening because of something Henry alluded to during the taping.

When I ask Henry if he ever questions whether the information he’s transmitting is accurate, he surprises me by admitting that he isn’t aiming for perfection. “I still sometimes am wrong,” he says. “I aim to be about 80 percent on.” He sometimes compares himself to a mailman, just delivering a message. But he’s okay with his odds. “I just kind of trust the process.”

On one episode of Life After Death, Henry visits his old elementary school and reminisces about what life was like before his psychic ability began to manifest. Things were simpler before the spirit presences, and before fame. “In order to survive, I’ve carved out a life for myself,” he says. “In my free time, the last thing I’m inclined to do is go to a club or go to a rave.” Early episodes of Hollywood Medium showed an assistant trying to get him to go out and party in L.A., but that plotline was quickly dropped.

His physical health has been imperiled for as long as he’s been famous. Around the time he started working on his first show, he started experiencing debilitating headaches and was diagnosed with a benign cyst in his brain that must be routinely drained when it gets too big, since it’s too dangerous to remove entirely. (“I have wondered if it relates to my ability at all,” Henry says.) He also suffered from a collapsed lung in 2019, and he has congenital blebs — small air-filled cysts — on his lungs, which must also be monitored. There are a lot of doctor’s appointments. Henry attributes these issues to the toll his work takes on his body and compares himself to a professional basketball player who keeps getting injured. “It’s the biggest question I have: Why, if this is something of a gift, does it come at a cost?” he says.

Stopping isn’t an option, either. If he goes too long without doing readings, feelings that aren’t his own begin crowding his consciousness. “If I want to take three weeks off, by week No. 2, I start feeling a little funny and even funnier and even funnier,” he tells me. “Why do I feel a connection to a divorced mother? Why do I feel sadness over not calling my alcoholic son? I don’t have an alcoholic son.” He has described the feeling as being “spiritually constipated.”

“I’m here for a good time, not necessarily here for a long time,” he says with his trademark smile. I ask him my last burning question: Will he and Clint ever get married? They’re getting hitched in December, actually, after rejecting an October 30 wedding date for being “too creepy.” Henry’s looking forward to the milestone. More than most people, he’s aware of life’s transience. As we gaze around at the gravestones and mausoleums that surround us, Henry reflects on his own eventual death. “Mortality is a constant in my life, in my work, in my personal life with my health struggles, death has touched every aspect,” he says. “And so when it comes time, it’ll be okay. I genuinely feel cool with it.” Left unsaid, because to Henry it’s obvious, is that believing you’ll be able to check in with your loved ones from the spirit realm probably makes death seem like much less of a big deal.