A frustrated African-American TV writer proposes a blackface minstrel show in protest, but to his chagrin, it becomes a hit.A frustrated African-American TV writer proposes a blackface minstrel show in protest, but to his chagrin, it becomes a hit.A frustrated African-American TV writer proposes a blackface minstrel show in protest, but to his chagrin, it becomes a hit.

- Awards

- 2 wins & 10 nominations total

Jada Pinkett Smith

- Sloan Hopkins

- (as Jada Pinkett-Smith)

Gillian White

- Verna

- (as Gillian Iliana Waters)

Yasiin Bey

- Big Blak Afrika

- (as Mos Def)

M.C. Serch

- Mau Mau: 1-16th Blak

- (as MC Serch)

Craig muMs Grant

- Mau Mau: Hard Blak

- (as Mums)

Dormeshia Sumbry

- Pickaninny: Topsy

- (as Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

I saw Bamboozled on cable years ago and could not watch the entire movie. I was very uncomfortable with the racist minstrel characters and those dehumanizing vintage toys. Flash forward to 2012 and I happened across it again. Wow, what a difference 10 years make. Since the election of Barack Obama, seemingly normal white people have lost their collective minds. They spent years denying the president's legal citizenship. They joined anti government Tea Party groups not because they did not wanted their big gov't social security checks but because they wanted to hang with a bunch of aging bigots carrying signs of the President dressed as a Kenyan native.

Where does Bamboozled fit in? These very same people love Herman Cain. It took me awhile but I finally got it, Mr Lee. Herman Cain is the Negro that white America is comfortable with. A self confessed sitting on the back of the bus entertaining... "awwwwww shucky ducky now" Negro. The Racist Tea Party folks could not get enough of him and his simplistic 9-9-9 plan. . When white women accused Mr Cain of sexual harassment, that just comforted them more because everyone knows Negros love white women. I guarantee you that if Herman Cain had darkened his skin with a burnt cork, the Tea Party folks would have lapped it up. His audience could have easily started to sport a black face too and proclaimed loudly to the press, "See we aren't racist!" The Herman Cain train exemplified everything that Spike Lee was saying in this dark comedy. Americans do not want to see African Americans represented by the Bill Cosby Show or the educated, functional Obama family. They want a minstrel show.

The movie is heartbreaking as is the behavior of many Americans. Thank you Spike Lee.

Where does Bamboozled fit in? These very same people love Herman Cain. It took me awhile but I finally got it, Mr Lee. Herman Cain is the Negro that white America is comfortable with. A self confessed sitting on the back of the bus entertaining... "awwwwww shucky ducky now" Negro. The Racist Tea Party folks could not get enough of him and his simplistic 9-9-9 plan. . When white women accused Mr Cain of sexual harassment, that just comforted them more because everyone knows Negros love white women. I guarantee you that if Herman Cain had darkened his skin with a burnt cork, the Tea Party folks would have lapped it up. His audience could have easily started to sport a black face too and proclaimed loudly to the press, "See we aren't racist!" The Herman Cain train exemplified everything that Spike Lee was saying in this dark comedy. Americans do not want to see African Americans represented by the Bill Cosby Show or the educated, functional Obama family. They want a minstrel show.

The movie is heartbreaking as is the behavior of many Americans. Thank you Spike Lee.

For the most part, Spike Lee is an angry filmmaker and I cannot blame his anger nor do I criticize it. With films such as Do the Right Thing and Jungle Fever, he shows his passion and understanding of situations such as racial feelings between all races, not just whites and blacks as well as how outsiders view interracial relationships. Here, his target is the entertainment industry, specifically television and he cuts right to the core because he knows how important and complex this issue is and wastes no time of this 135-minute film to stuff every frame and scene with a message and relating what he has seen in this country and how he feels about it.

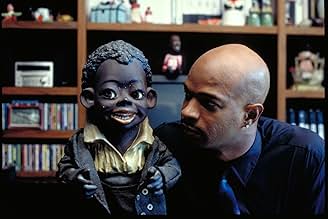

First off, the acting is near flawless. Damon Wayans gives his best performance ever as Pierre Delacroix, a successful producer upset that he is not considered black with his fancy dress and white accent. Determined to make his case, he decides to create a minstrel show very much in the vein of those from the 1930s and 40s. However, he goes one step further and hires black actors to use blackface makeup as well as make the subject and setting the most politically incorrect setups imaginable. What he doesn't expect is the overwhelming popularity of the show complete with huge ratings and numerous critical awards.

For my money, Lee almost had a great film here. The first hour is terrific, biting satire, attacking everything and anything. Lee takes no prisoners and also gives some very interesting bits about how a TV show is brought to life. But, once the show becomes a success and the people involved develop consciences, Lee's vision narrows and soon it becomes more of the angry and socially-aware Spike Lee we've seen in much better films. Being white myself, I never liked how Lee seemed to portray whites as leering fools and the true ignorant people of America as opposed to the "more commonly accepted" view of blacks. Still, his feelings were justified in Do the Right Thing, Jungle Fever and earlier works. Bamboozled tries too hard and loses its mission towards the end. The end is in fact a rehash of many other movies seen before, even ones self-consciously referred to here such as Network and The Producers.

Spike Lee is a gifted and fearless director and I cannot say this is a boring or uninspiring film. I was held captive every step of the way. I just wish he had picked a better and more effective way to satirize his subjects, as well as maybe broaden the horizons; only then could it really take root.

First off, the acting is near flawless. Damon Wayans gives his best performance ever as Pierre Delacroix, a successful producer upset that he is not considered black with his fancy dress and white accent. Determined to make his case, he decides to create a minstrel show very much in the vein of those from the 1930s and 40s. However, he goes one step further and hires black actors to use blackface makeup as well as make the subject and setting the most politically incorrect setups imaginable. What he doesn't expect is the overwhelming popularity of the show complete with huge ratings and numerous critical awards.

For my money, Lee almost had a great film here. The first hour is terrific, biting satire, attacking everything and anything. Lee takes no prisoners and also gives some very interesting bits about how a TV show is brought to life. But, once the show becomes a success and the people involved develop consciences, Lee's vision narrows and soon it becomes more of the angry and socially-aware Spike Lee we've seen in much better films. Being white myself, I never liked how Lee seemed to portray whites as leering fools and the true ignorant people of America as opposed to the "more commonly accepted" view of blacks. Still, his feelings were justified in Do the Right Thing, Jungle Fever and earlier works. Bamboozled tries too hard and loses its mission towards the end. The end is in fact a rehash of many other movies seen before, even ones self-consciously referred to here such as Network and The Producers.

Spike Lee is a gifted and fearless director and I cannot say this is a boring or uninspiring film. I was held captive every step of the way. I just wish he had picked a better and more effective way to satirize his subjects, as well as maybe broaden the horizons; only then could it really take root.

This is Lee's best film. It isn't heavy handed despite the explosive topic. In fact I would argue that the images in this film are less offensive then some of the depiction of African-American life seen on MTV or BET. Less heavy handed then some of the vulgar depiction of my community that is allowed to be foisted on my community as entertainment. The modern minstrels show can be seen any night of the week on America's cable music networks. Which is more embarrassing Lil'John, 50 cent or Mantan? Which has had a bigger impact on the daily lives of African-American children, images of Step- N-Fetch it or Lil'John? Which are the stereotypes that are used to justify racial profiling in the larger public of the country in 2006, Gangstas or minstrels performers? It is a film about the power and responsibility of black America to control the images that define it.

I think Lee for the first time in a long time had a story he actually wanted to tell. The script was solid if not great. As usual Spike had a tough time with his female characters. The women in his films tend to be two dimensional. All good or all bad. It wasn't a perfect film but I think it will be remembered as one of Spike's most interesting.

I think Lee for the first time in a long time had a story he actually wanted to tell. The script was solid if not great. As usual Spike had a tough time with his female characters. The women in his films tend to be two dimensional. All good or all bad. It wasn't a perfect film but I think it will be remembered as one of Spike's most interesting.

I was lucky enough to see the Philadelphia premiere of this movie at the U. of Penn, with Spike Lee in attendance, and I left the theatre feeling almost speechless. I've seen most of Lee's films and have mixed emotions and reviews of each of them; however, this film is truly a MASTERPIECE of filmmaking. Without giving away the many-layered plot, which must be experienced to be appreciated, the subject is a touchy one --- controversial and poignant, embarrassing and humiliating, enlightening and insightful. Mainstream white audiences ( of which I am a part ) may find the subject to be uncomfortable --- obviously one of Lee's goals here --- and all audiences will find certain parts of the movie to be terrifying. Besides the storyline, the acting is wonderful across the board, and Daman Wayans deserves an Academy Award for his over-the-top role. Spike Lee's "Bamboozled" should go down in history as one of the most important films about race vs. social status and the misconceptions and stereotypes that surround them, as well as being a magnificent movie about popular culture and the almighty dollar. It is alternatingly hysterical, contemplative, witty and violent, and I left the theatre in tears, totally speechless. Unfortunately, this will probably be a short-lived film in your local cineplex, but hopefully it will gain enough serious attention to win the accolades it deserves, as well as open some closed eyes and minds.

I want to like Spike Lee. He's an important film-maker whose work refuses to let us forget our past or ignore the present it's created. His career has been devoted to asking questions no one wants to answer, and such courage rare in Hollywood - is something to value. What frustrates me is that his films rarely live up to the ideas behind them, and Bamboozled is no exception.

It presents his most interesting idea and biggest disappointment to date. Harvard-educated screenwriter Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) is frustrated. The sole black writer at his network, his ideas for shows featuring the black middle class are rejected one after the other. His white station manager wants something more real real meaning poor, undereducated and armed, the kind of `real' we see in gangsta rap videos. In reply, Delacroix creates The New Millennium Minstrel Show, a black-face variety show that will fail so badly and outrage so many he'll be freed from his contract. Hosted by Mantan and Sleep n' Eat, the show is set in a plantations watermelon patch, filled with sketches where the duo steal chickens from their overseer's coop. The pilot is a hit and suddenly Delacroix finds his creation out of his control.

Bamboozled was a hard film to finance and its struggle points to its importance, but despite its wealth of ideas the execution is poor and reeks of an opportunity missed. Much of its failure comes from the central performance by Wayans, a frankly bizarre turn that irritates from the first word. His Delacroix, uncomfortable in his skin, has changed his name and much of his accent. What remains is an impression of an upper-class white man which is just that an impression. It's a superficial performance, a pantomime out of place among the more subtle performances that surround it. I appreciate its point, that Delacroix is ashamed of his origins, but it misses the target and does nothing but grate.

Beyond that, Bamboozled is underwritten and feels under-rehearsed. The character development is sloppy, huge changes in personality coming without warning and with little credibility. Add to that a clichéd friendship-not-surviving-success subplot and big ideas apparently lifted from The Producers and Network, and there seems little left to praise.

But while it fails on many levels, the good ideas remain and allow Lee to explore two main themes the past degradation of black performers and the position they hold today. We learn that black artists in minstrel shows or movies had little choice but to degrade themselves if they wished to pursue a career in entertainment. They were only allowed to be greedy, lazy, bug-eyed buffoons, stripped of their dignity so white audiences could enjoy them without addressing their prejudices. Willie Best, an actor from the 1930s who himself performed under the name Sleep n' Eat once asked 'What's an actor going to do? Either you do it or get out."

Addressing the status of today's black performers in a number of interviews, Lee has accused gangsta rap of being `the 21st century minstrel show'. It's an interesting argument, seeing that its lyrics and videos give overwhelmingly negative images of contemporary black culture that are lapped up by young white audiences. Theft, drug use and abuse, violence against women, murder as entertainment; these are the means by which the rappers degrade themselves for their listeners. The Mau-Maus, the gangsta rappers in the film who take issue with the New Millennium Minstrel Show represent these ideas, though how well they do so is questionable. On the subject of blacks in film, Lee has condemned the use of `Super Magical Niggers' in the likes of The Green Mile and The Legend of Bagger Vance, men who `use magic to help white people but can't help themselves.' Hollywood is still limiting the kinds of black films they'll make, choosing mostly gangsta, hip-hop shoot-em-ups or lowbrow comedy. The same is true of TV, where `about 95% of blacks on television now are working on sit-coms.' Where are the all-black dramas? With gangsta rap, the dominance of lowbrow comedy on TV, and simplified fairytale roles or drug-centred grit in cinema, it seems that black entertainment in the white world still relies on degradation, stereotype or cheap laughs. And although much of Lee's argument can be countered by a number of positive roles or by seeing gangsta rap as only a small part of the black music that dominates the charts, these are the things Bamboozled wants to make us think about. Unfortunately, Lee's interviews that publicised the films are far more interesting, persuasive and thoughtful than the film itself.

Perhaps that's the problem. He's an interesting thinker but seems to have difficulty in wrapping his arguments around plot, pace and character. The finest moments in Bamboozled come when he's not weighed down by those burdens. The last few minutes feature a fantastic montage of film and TV's shameful past. We see the obvious clips from Birth of a Nation and The Jazz Singer but are surprised to see Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney and Bing Crosby applying blackface. When these films are shown on US television these moments are edited out Lee even came across a cartoon of Bugs Bunny in blackface that Warner Brothers wouldn't allow him to include. The end credits house an equally shocking montage of racist memorabilia such as `The Hungry Nigger Bank' from Lee's own collection. Had Bamboozled boasted that intensity throughout, had it not been let down by a script that fails to make its points, by Damon Wayan's superficial take on the lead role, and its betrayal of supporting characters for its finale, it would have been a fascinating film. As it is, the message is powerful; the film is not.

But when his films work and when they don't, Spike Lee is at least consistent in one thing; he makes you think long after the credits have rolled. That's a responsibility and an opportunity that too many filmmakers are afraid to take on.

It presents his most interesting idea and biggest disappointment to date. Harvard-educated screenwriter Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) is frustrated. The sole black writer at his network, his ideas for shows featuring the black middle class are rejected one after the other. His white station manager wants something more real real meaning poor, undereducated and armed, the kind of `real' we see in gangsta rap videos. In reply, Delacroix creates The New Millennium Minstrel Show, a black-face variety show that will fail so badly and outrage so many he'll be freed from his contract. Hosted by Mantan and Sleep n' Eat, the show is set in a plantations watermelon patch, filled with sketches where the duo steal chickens from their overseer's coop. The pilot is a hit and suddenly Delacroix finds his creation out of his control.

Bamboozled was a hard film to finance and its struggle points to its importance, but despite its wealth of ideas the execution is poor and reeks of an opportunity missed. Much of its failure comes from the central performance by Wayans, a frankly bizarre turn that irritates from the first word. His Delacroix, uncomfortable in his skin, has changed his name and much of his accent. What remains is an impression of an upper-class white man which is just that an impression. It's a superficial performance, a pantomime out of place among the more subtle performances that surround it. I appreciate its point, that Delacroix is ashamed of his origins, but it misses the target and does nothing but grate.

Beyond that, Bamboozled is underwritten and feels under-rehearsed. The character development is sloppy, huge changes in personality coming without warning and with little credibility. Add to that a clichéd friendship-not-surviving-success subplot and big ideas apparently lifted from The Producers and Network, and there seems little left to praise.

But while it fails on many levels, the good ideas remain and allow Lee to explore two main themes the past degradation of black performers and the position they hold today. We learn that black artists in minstrel shows or movies had little choice but to degrade themselves if they wished to pursue a career in entertainment. They were only allowed to be greedy, lazy, bug-eyed buffoons, stripped of their dignity so white audiences could enjoy them without addressing their prejudices. Willie Best, an actor from the 1930s who himself performed under the name Sleep n' Eat once asked 'What's an actor going to do? Either you do it or get out."

Addressing the status of today's black performers in a number of interviews, Lee has accused gangsta rap of being `the 21st century minstrel show'. It's an interesting argument, seeing that its lyrics and videos give overwhelmingly negative images of contemporary black culture that are lapped up by young white audiences. Theft, drug use and abuse, violence against women, murder as entertainment; these are the means by which the rappers degrade themselves for their listeners. The Mau-Maus, the gangsta rappers in the film who take issue with the New Millennium Minstrel Show represent these ideas, though how well they do so is questionable. On the subject of blacks in film, Lee has condemned the use of `Super Magical Niggers' in the likes of The Green Mile and The Legend of Bagger Vance, men who `use magic to help white people but can't help themselves.' Hollywood is still limiting the kinds of black films they'll make, choosing mostly gangsta, hip-hop shoot-em-ups or lowbrow comedy. The same is true of TV, where `about 95% of blacks on television now are working on sit-coms.' Where are the all-black dramas? With gangsta rap, the dominance of lowbrow comedy on TV, and simplified fairytale roles or drug-centred grit in cinema, it seems that black entertainment in the white world still relies on degradation, stereotype or cheap laughs. And although much of Lee's argument can be countered by a number of positive roles or by seeing gangsta rap as only a small part of the black music that dominates the charts, these are the things Bamboozled wants to make us think about. Unfortunately, Lee's interviews that publicised the films are far more interesting, persuasive and thoughtful than the film itself.

Perhaps that's the problem. He's an interesting thinker but seems to have difficulty in wrapping his arguments around plot, pace and character. The finest moments in Bamboozled come when he's not weighed down by those burdens. The last few minutes feature a fantastic montage of film and TV's shameful past. We see the obvious clips from Birth of a Nation and The Jazz Singer but are surprised to see Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney and Bing Crosby applying blackface. When these films are shown on US television these moments are edited out Lee even came across a cartoon of Bugs Bunny in blackface that Warner Brothers wouldn't allow him to include. The end credits house an equally shocking montage of racist memorabilia such as `The Hungry Nigger Bank' from Lee's own collection. Had Bamboozled boasted that intensity throughout, had it not been let down by a script that fails to make its points, by Damon Wayan's superficial take on the lead role, and its betrayal of supporting characters for its finale, it would have been a fascinating film. As it is, the message is powerful; the film is not.

But when his films work and when they don't, Spike Lee is at least consistent in one thing; he makes you think long after the credits have rolled. That's a responsibility and an opportunity that too many filmmakers are afraid to take on.

Did you know

- TriviaMost of this film was shot only on digital (Mini DV) camcorders, which can be purchased over the counter at any consumer electronics store. While this choice of technology sacrificed quality, it allowed the cinematographers to film with 15 cameras at a time, and it also allowed Spike Lee to get all the footage he needed shot within the film's modest budget. The "Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show" sequences were the only scenes shot using 16mm film.

- GoofsOne character uses the phrase "drinking the Kool-Aid", a reference to the mass murder/suicide of the Peoples Temple cult in Jonestown, Guyana. The poisoned drink was Flavor-Aid. The pavilion was surrounded by armed guards, and anyone who did not drink the poisoned drink willingly (including children) was either forced to drink it or injected with poison. A number of the bodies had puncture or bullet wounds. Jim Jones died of a gunshot wound to the head, that may have been self-inflicted.

- Quotes

Myrna Goldfarb: I happen to have a Master's degree in African-American studies.

Pierre Delacroix: So you fucked a nigger in college.

- Crazy creditsThe credits roll over several "coon" collectable items that are wound-up.

- How long is Bamboozled?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $10,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $2,274,979

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $190,720

- Oct 8, 2000

- Gross worldwide

- $2,463,650

- Runtime2 hours 15 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.78 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content