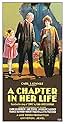

Jewel stays with her grizzled, angry grandfather while her parents are overseas on business. Family squabbling is brought to heel through love and understanding from Jewel's pure love for ot... Read allJewel stays with her grizzled, angry grandfather while her parents are overseas on business. Family squabbling is brought to heel through love and understanding from Jewel's pure love for others and trust in Divine LoveJewel stays with her grizzled, angry grandfather while her parents are overseas on business. Family squabbling is brought to heel through love and understanding from Jewel's pure love for others and trust in Divine Love

Photos

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- ConnectionsReferenced in The Silent Feminists: America's First Women Directors (1993)

Featured review

A child, Jewel (played with a bright smile by Jane Mercer), is the only hope for the inhabitants of "Castle Discord". The spiteful antagonists include her grandfather and his maid pit against her widowed aunt and her aunt's daughter. There's more story here than in the other films I've seen by Lois Weber. She still includes a message or two, though. That was her goal with film-making--to deliver morality to the public. This time, her message was something along the lines of: hate and classism are bad, and if we all got along, we'd be happier. I found the message, or, rather, the story, somewhat heartwarming. Only the heavy-handed teetotalism comes off as ridiculous.

(Note: The print I saw was slightly worn.)

Addendum (10 April 2021):

Before watching the Kino-Lorber Blu-ray of "A Chapter in Her Life," as paired with "Sensation Seekers" (1927), I last saw this Lois Weber feature over 15 years ago on a Facets VHS. I still agree with my brief and old review regarding "A Chapter in Her Life" being a morality tale, but I failed to mention that the message is decidedly one of Christian Science, as based on the novel "Jewel: A Chapter in Her Life" by Clara Louise Burnham. Besides not having done my research, I probably neglected this because the film goes out of its way to never mention it explicitly.

But, as more recent Weber scholars, like Shelley Stamp in her book "Lois Weber in Early Hollywood" and Marcia Landy in her article "A Chapter in Her Life (1923): A 'Chapter' on the History, Aesthetics and Ethics of Lois Weber's Filmmaking," have made clear, there are plenty of telltale signs of the subtle Christian Science proselytizing. Burnham was a Christian Scientist herself, and "Jewel" was one in a series of books she wrote incorporating the ideas of Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Church of Christ, Scientist, into stories, such as this one that delivers them through the Victorian-ideal child type, Jewel. Perhaps what most stands out with this understanding of the film is the sequence where Jewel refuses medicine for whatever undiagnosed illness she recovers from miraculously or naturally, as the religion is most popularly known for its adherents' avoidance of medical treatment. Otherwise, we see Jewel showing adults a book or two as she cures "Castle Discord" of, well, its discord--one of the books presumably being Eddy's "Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures."

Befitting this literary religiosity (heck, the first I remember learning of Christian Science was their newspaper "The Monitor," the mostly-secular and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalistic integrity of which struck me as rather odd as I learned more about the sect), there's a letter motif throughout "A Chapter in Her Life," including notes of wisdom Jewel reads from her mother. Technically, this isn't one of Weber's more outstanding films--Anthony Slide (in his book "The Director Who Lost Her Way in History") went so far as to dismiss it as a "nothing more than a program picture," despite Universal releasing it as one of their prestigious Jewel productions. One thing, however, that did stand out to me upon a second viewing was a bit of psychologically-motivated cutting to subjective imagery in the early scenes. When one character plays the piano, it conjures emotional visuals, or we see the now-sober son as a drunkard when his father remembers him, and Jewel's parents are momentarily fretted over as a ship in a stormy sea are imagined. There's also at least one mirror shot where Jewel is seen in a space that is otherwise out of frame, and there's her reflection in a pool of water in another scene.

Anyways, the film is more interesting for how it fits into director Weber's oeuvre of cinematic lectures, especially as this was a female filmmaker adapting a female author's book, which in turn was rooted in a religion founded by a woman. Christian Science seems to have been even more controversial back in the 1920s, too, than it is now, although it was also receiving increased publicity. Stamps notes that actress Leatrice Joy, who Weber directed in her last silent film, "The Angel of Broadway" (1927), was a Christian Scientist, and that Mary Pickford propagated Eddy's teachings in a ghost-written book of hers. Weber herself, reportedly, wasn't an adherent, although she clearly shared some beliefs, including the work of women in the public sphere. Indeed, Weber had previously adapted Burnham's book as "Jewel" (1915), and Slide says that Weber also proselytized Eddy's values in "A Leper's Coat" (1914), and Stamp notes that Weber penned the screenplay for an adaptation of another Burnham book with "The Opened Shutters" (1914) (all three films are now lost, as is "The Angel of Broadway").

Weber seems to have been an Evangelical Christian of German descent, but her films welcome a variety of Christian faiths, at least, as well as her perhaps somewhat misguided, as one may glean from the title, attempt to rebuke anti-Semitism in "A Jew's Christmas" (1913, and, yes, also since lost). "The Rosary" (1913), for instance, is notable for its Catholic story involving nuns, and the entire film being framed as a circular rosary vignette. Weber was also repeatedly critical of gossip and the hypocrisy of church-goers, as depicted from "Hypocrites" (1915) to "Sensation Seekers."

(Note: The print I saw was slightly worn.)

Addendum (10 April 2021):

Before watching the Kino-Lorber Blu-ray of "A Chapter in Her Life," as paired with "Sensation Seekers" (1927), I last saw this Lois Weber feature over 15 years ago on a Facets VHS. I still agree with my brief and old review regarding "A Chapter in Her Life" being a morality tale, but I failed to mention that the message is decidedly one of Christian Science, as based on the novel "Jewel: A Chapter in Her Life" by Clara Louise Burnham. Besides not having done my research, I probably neglected this because the film goes out of its way to never mention it explicitly.

But, as more recent Weber scholars, like Shelley Stamp in her book "Lois Weber in Early Hollywood" and Marcia Landy in her article "A Chapter in Her Life (1923): A 'Chapter' on the History, Aesthetics and Ethics of Lois Weber's Filmmaking," have made clear, there are plenty of telltale signs of the subtle Christian Science proselytizing. Burnham was a Christian Scientist herself, and "Jewel" was one in a series of books she wrote incorporating the ideas of Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Church of Christ, Scientist, into stories, such as this one that delivers them through the Victorian-ideal child type, Jewel. Perhaps what most stands out with this understanding of the film is the sequence where Jewel refuses medicine for whatever undiagnosed illness she recovers from miraculously or naturally, as the religion is most popularly known for its adherents' avoidance of medical treatment. Otherwise, we see Jewel showing adults a book or two as she cures "Castle Discord" of, well, its discord--one of the books presumably being Eddy's "Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures."

Befitting this literary religiosity (heck, the first I remember learning of Christian Science was their newspaper "The Monitor," the mostly-secular and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalistic integrity of which struck me as rather odd as I learned more about the sect), there's a letter motif throughout "A Chapter in Her Life," including notes of wisdom Jewel reads from her mother. Technically, this isn't one of Weber's more outstanding films--Anthony Slide (in his book "The Director Who Lost Her Way in History") went so far as to dismiss it as a "nothing more than a program picture," despite Universal releasing it as one of their prestigious Jewel productions. One thing, however, that did stand out to me upon a second viewing was a bit of psychologically-motivated cutting to subjective imagery in the early scenes. When one character plays the piano, it conjures emotional visuals, or we see the now-sober son as a drunkard when his father remembers him, and Jewel's parents are momentarily fretted over as a ship in a stormy sea are imagined. There's also at least one mirror shot where Jewel is seen in a space that is otherwise out of frame, and there's her reflection in a pool of water in another scene.

Anyways, the film is more interesting for how it fits into director Weber's oeuvre of cinematic lectures, especially as this was a female filmmaker adapting a female author's book, which in turn was rooted in a religion founded by a woman. Christian Science seems to have been even more controversial back in the 1920s, too, than it is now, although it was also receiving increased publicity. Stamps notes that actress Leatrice Joy, who Weber directed in her last silent film, "The Angel of Broadway" (1927), was a Christian Scientist, and that Mary Pickford propagated Eddy's teachings in a ghost-written book of hers. Weber herself, reportedly, wasn't an adherent, although she clearly shared some beliefs, including the work of women in the public sphere. Indeed, Weber had previously adapted Burnham's book as "Jewel" (1915), and Slide says that Weber also proselytized Eddy's values in "A Leper's Coat" (1914), and Stamp notes that Weber penned the screenplay for an adaptation of another Burnham book with "The Opened Shutters" (1914) (all three films are now lost, as is "The Angel of Broadway").

Weber seems to have been an Evangelical Christian of German descent, but her films welcome a variety of Christian faiths, at least, as well as her perhaps somewhat misguided, as one may glean from the title, attempt to rebuke anti-Semitism in "A Jew's Christmas" (1913, and, yes, also since lost). "The Rosary" (1913), for instance, is notable for its Catholic story involving nuns, and the entire film being framed as a circular rosary vignette. Weber was also repeatedly critical of gossip and the hypocrisy of church-goers, as depicted from "Hypocrites" (1915) to "Sensation Seekers."

- Cineanalyst

- Jan 25, 2005

- Permalink

Details

- Runtime1 hour 3 minutes

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was A Chapter in Her Life (1923) officially released in Canada in English?

Answer