Last updated on July 21st, 2022 at 09:20 pm

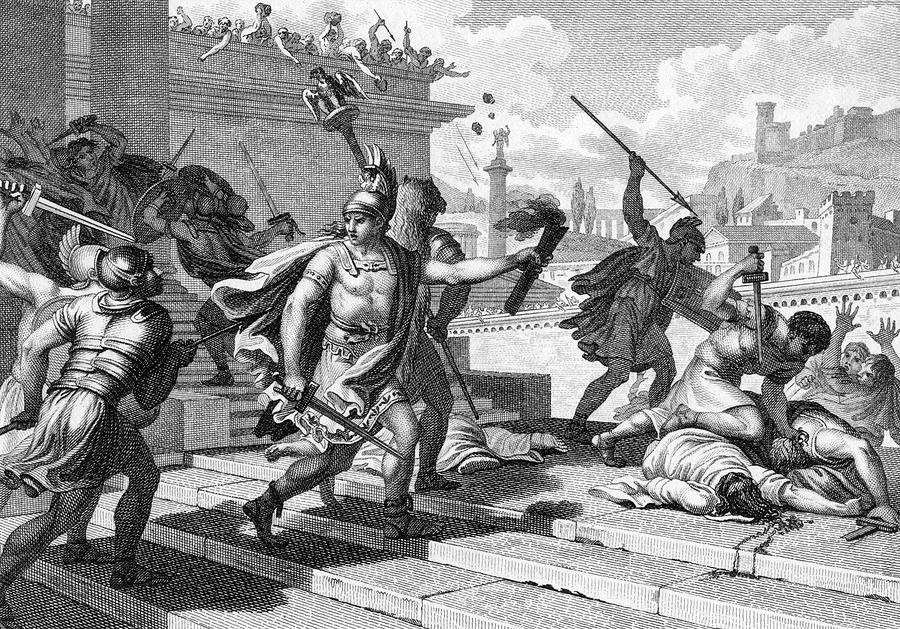

On 1 November 82 BC, a battle took place virtually within the city of Rome itself.

It was a climactic end to a civil war that began the previous between the supporters of the Roman general, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and an alliance of Marians.

The Marians were supporters of the recently deceased military commander, Gaius Marius, now led by his son, Marius the Younger, and a prominent Roman politician, Gaius Papirius Carbo.

The engagement took place at the Porta Colline, the Colline Gate, an entryway to the city of Rome constructed in the sixth century BC.

Our sources for the Battle of the Colline Gate are surprisingly scarce for such a crucial battle in Rome’s history, but what is clear is that this was the culmination of a long march by Sulla on the city of Rome and that he emerged victorious by the end of the day’s fighting.

It was one of the most striking episodes in the long process whereby the Roman Republic gradually collapsed in the first century BC. So here we explore why Sulla marched on Rome?

Who Was Lucius Cornelius Sulla?

Let’s backtrack a little first to see who the man who led this march even was. Lucius Cornelius Sulla was born around 138 BC into a prominent patrician family in Rome.

This time was a period of immense instability in the Roman Republic. Although Rome was never as strong militarily, expanding with enormous speed all over the Mediterranean, internally, the Republic was massively unstable.

There were calls for Roman citizenship to be extended to more of the state’s free subjects and to distribute its spoils more widely.

Most significantly, as its armies expanded and it undertook new conquests in North Africa, Greece, Asia Minor, and the Levant, Rome’s generals acquired enormous power and were increasingly difficult to control for the Roman Senate and the established political institutions.

Sulla would emerge as one of these over-mighty generals. He first rose to prominence in the late second century BC commanding an army in North Africa against the Numidian King Jugurtha.

He used this military command as a springboard to acquire several prominent political offices in Rome itself and then to become one of the foremost commanders in defense of northern Italy from the Cimbric Celts in the very last years of the second century BC.

By the 90s BC, he had become one of the most influential figures within the Republic. But he had a rival for power: Gaius Marius.

Rivalry with Marius

Marius was about twenty years older than Sulla. He was already the leading Roman general of the day in the 100s BC when Sulla began to gain praise for his military abilities.

Consequently, the two men soon became rivals. In the 90s BC, this resulted in their leadership of the two main political factions within the Roman Republic.

Marius became the leader of the populares, a grouping that sought to appeal to a broad base of support amongst Rome’s citizens, both rich and poor.

In contrast, Sulla became the leader of the optimates faction, which believed control of the Republic should continue to reside in the hands of the established patrician families of Rome.

Today we would call Sulla a conservative and Marius a populist. Their rivalry was briefly put aside in 91 BC when a conflict known as the Social War broke out across Italy.

In this, the free people of the wider peninsula, who Rome had ruled since the fourth and third centuries BC, went to war with the city authorities to demand that they be given Roman citizenship themselves.

This civil conflict lasted for several years. It was eventually defeated, though a decision was taken anyway to extend Roman citizenship to all Italians in its aftermath. However, the Social War only delayed the outbreak of further tensions between Sulla and the Marians.

The Outbreak of the Civil War

By 88 BC, the Social War was essentially over in Italy. Consequently, the republican authorities had once more begun to turn their eyes eastwards to conquer new lands in the Eastern Mediterranean, notably King Mithridates VI of Pontus, a kingdom that ruled much of modern-day Turkey, Georgia, and the coast of the Black Sea.

Mithridates was attempting to extend his influence into Greece. The Roman Senate had determined that they should send the Roman army eastwards to curb the expansion of this foreign kingdom and bring Pontus to heel.

Marius and Sulla were rivals for the honor of commanding this army. Still, Sulla, who had become the consul for 88 BC, the senior political magistrate in the Roman Republic, won the position and was sent eastwards with a large army.

He would win several significant battles against the King of Pontus in Greece, Athens, and Chaeronea in 86 BC. With this done, he crossed over into Asia Minor and campaigned against Mithridates’s territories in what is now northern Turkey.

However, by that stage, Sulla’s heart had gone out of the fight against the King of Pontus, for it was clear that events had overtaken him back home.

In his absence, Marius and his allies had effectively seized control of the government of the Republic and were attempting to remove Sulla’s followers from positions of power.

Marius died early in 86 BC, but his political faction, known to posterity as the Marians, was continued and taken over by his son Marius the Younger and politicians such as Carbo and Lucius Cornelius Cinna.

Sulla’s March on Rome

It was in this context that Sulla began planning his next move. He settled with King Mithridates in 85 BC, whereby the King of Pontus renounced his earlier conquest of Greece. The Kingdom of Bithynia in Asia Minor effectively became a Roman client state.

Then Sulla began building up his forces to head back westwards to Rome and crush the Marians. Thus he launched what has become known as Sulla’s Civil War in 83 BC.

At the outset, he was massively outnumbered, heading westwards with approximately six legions or 30,000 men, whereas the Marians had nearly 100,000 troops.

In the following months, though, Sulla won a series of spectacular victories after landing in southern Italy in the spring of 83 BC.

Once he established himself there, many of the old Roman nobility also began deserting the Marians and flocked southwards, bringing thousands of troops.

He spent the next year and a half building up his position here until, in the autumn of 82 BC, he felt strong enough to march against Rome. The result was the Battle of the Colline Gate on 1 November.

In this, Sulla’s army emerged victorious, and as they entered Rome itself, the city’s people threw open the gates and allowed him to take the city without further bloodshed. Sulla had won his civil war.

Dictatorship, Retirement, and Death

Sulla’s victory in the civil war made him the most prominent figure in the Roman Republic. He confirmed this by having himself granted the power of dictatores.

This power within the Roman constitution was granted to magistrates for a brief period in extraordinary times to deal with a political emergency.

Using these new powers, Sulla launched a series of proscriptions whereby the main leaders of the Marian faction were arrested and executed by the government.

These included figures like Marian the Younger and Carbo. About 500 Marians were killed and their lands confiscated. A young Gaius Julius Caesar, who had been a Marian himself, only barely escaped with his life. What is unusual about Sulla, though, is that he soon renounced his power.

In 80 BC, he served as consul again, and there were fears he would cling to power, but in 79 BC, he gave up all his political offices and power, including the power of dictatores.

He then retired to his country villa, possibly from an intestinal ulcer, where he died the following year.

However, he set a dangerous precedent. In the following decades, new generals such as Pompeius Magnus and Julius Caesar began vying for the dominant position Sulla had obtained earlier.

Eventually, these internecine conflicts would bring the Roman Republic to an end and see the rise of the Roman Emperors.