What’s Past is Prologue…Maybe

In one of the least heralded of his latest flurry of transactions, the M’s picked up right-handed reliever Shawn Armstrong from the Cleveland Indians in exchange for some of the international bonus pool spending authority they’d accumulated to try and sign Shohei Otani. Armstrong has never started, and though he bounced around the fringes of the Indians’ top 20 list, the sense that he was destined for middle relief limited his appeal as a real prospect. He’s now out of options, a fact that may see him signed/released by several teams in the next few months.

Armstrong’s thrown 43+ innings in three separate stints with the Tribe, accumulating zero runs above replacement. Do projection systems see untapped potential here? Er, no, they see a guy who’s been replacement-level and project him as…replacement level. There’s nothing really shocking here, despite some gaudy AAA strikeout rates. Those haven’t quite translated to the big leagues, and his walk rates are scary, and, perhaps most importantly, big league relievers – as a group – are really, really good now. You don’t look at Armstrong’s Fangraphs page and see someone likely to help immediately. And since he’s out of options, you *also* don’t see a project who might work something out in Tacoma.

This blog, at its core, has been organized around the idea that the right statistics give us some insight into a pitcher’s talent, and that a pitcher’s results are, given a decent sample, related to that talent. Variance/luck/etc. will result in some mismatches between talent and results, and again, that’s where the stats can be valuable – they can aid in identifying undervalued players. In the main, on average, this theory works pretty well. A great pitcher whose results are sullied by a freakishly high BABIP will likely post better results down the road. Individual players can change, and the very phrase “true talent” almost implies something immutable or fixed, something that’s not true at all. But every game post, I’m looking at, say, pitch fx data or FIP or something other than a guy’s W/L record, or how’s he’s fared against AL West teams on Tuesday nights, because those numbers give us some sense of what we’re going to see. If you look at Shawn Armstrong’s numbers, you’re not encouraged. If past is prologue, then Armstrong will cycle through a bunch of teams as he’s waived, and will eventually sign a minor league deal with an opt-out.

But Armstrong looks…familiar. Here’s a table featuring one of the ol’ stand-by blogging devices – my apologies, it’s December and I’m not feeling creative at all:

| FB Spin | FB Vert. Movement | FB Horiz. Movement | Cutter Spin | Cutter Vert. Movement | Cutter Horiz. Movement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player A | 2396 | 9.28 | -3.71 | 2483 | 5.78 | 1.37 |

| Player B | 2363 | 9.3 | -2.82 | 2486 | 4.83 | 1.21 |

Player A throws a four-seam fastball with 2396 RPM spin, while Player B’s at 2363. For context, the league average value last season was 2255; 632 players threw at least 25 four-seamers (including Chris Gimenez? Really?), and so both A and B are solidly in the top 3rd in spin rate. Movement-wise, the pitches are even more freakishly similar – just 2 hundreths of an inch difference in vertical rise, and less than an inch in horizontal break (there’s very little of it from either hurler). They both throw cutter/slider things, and both are thrown hard (meaning thrown at a velocity close to their fastball), and with a bit of cut and sink. These cutters have high spin rates as well; the league average is 2344, and A and B are next to each other on the spin rate leaderboards (in the top 1/4th). High spin fastball and high spin cutter – if you thought “Nick Vincent” congratulations, he’s Player A. B is Armstrong. Remember that Vincent was signed when HE was out of options and could’ve been waived by the Padres. Vincent had had much more big league success, but was essentially freely-available back before the 2016 season.

Vincent never threw as hard as Armstrong, but – and I’d actually forgotten this – used his cutter and fastballs to dominate righties. Lefties ate him alive, but he really controlled righties, which is something I wrote about when the M’s picked him up. With the M’s, Vincent’s shown essentially no platoon splits, and has handled lefties remarkably well. Vincent and the M’s took something that was a part of his statistical record and changed it. It’s still too early to say definitively whether this is variation or if his “true talent” changed, but the M’s got two solid years out of Vincent – two years in which he’s been dominant against lefties, a fact that’s enabled him to pitch in higher leverage situations and to face more batters than anyone relying on his fangraphs page would’ve expected. I’ve beaten the M’s up these past two years for their mediocre record in player development and their inability to keep players around long enough to try, but Vincent’s a – maybe THE – example of a clear-cut developmental success.

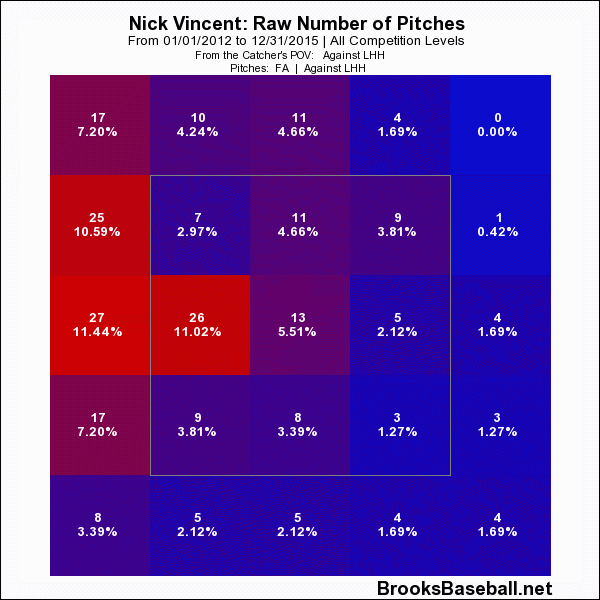

One of the keys has been how Vincent attacks lefties, something Jerry Dipoto talked about with regard to Juan Nicasio in the last Wheelhouse podcast. Here’s where Vincent spotted his fastball against lefties with the Padres:

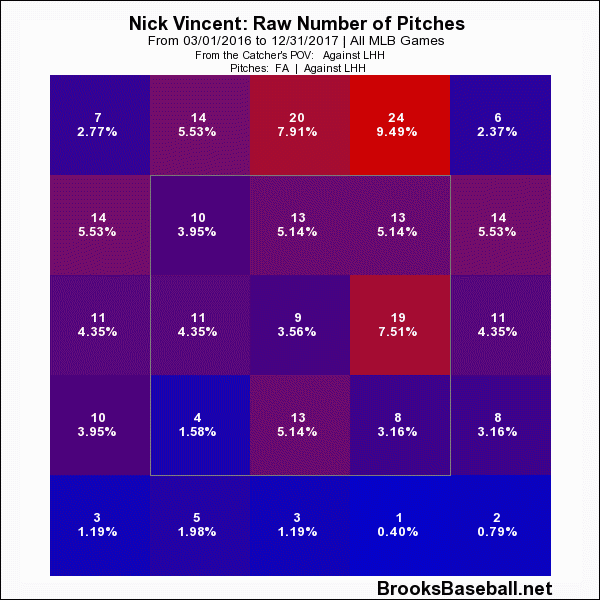

This usage reflects a pretty common idea: righties should keep fastballs away from lefties – or righties, for that matter. It’s harder to pull them, after all, and thus harder to drive. Vincent threw his fastballs up and middle-away to righties, and away to lefties. It worked against righties, and didn’t work at all against lefties. What’s he done with the Mariners?

There’s no longer a clear difference in how he attacks lefties and righties: both get elevated four-seam fastballs, and lefties are now more likely to see an *inside* fastball than an away version. To understand why the M’s might prefer this approach, we’ll go back to the Wheelhouse podcast and Jerry’s discussion of “effective velocity” in episode 2. Here, they’re not referring to the effective velocity measurement in statcast, which accounts for a pitcher’s stride toward the plate. Instead, he’s referring to Perry Husband’s concept. A hitter needs less time to get his bat to an away fastball than he does to an inside fastball. A down and away fastball isn’t worthless, but because a batter can react later to it, it makes the pitch seem slower – a batter needs less time to put that pitch in play than a fastball with the exact same velocity thrown inside. Vincent stopped turning his 89-MPH heater into an effectively-86-MPH heater, and became an all-around reliever.

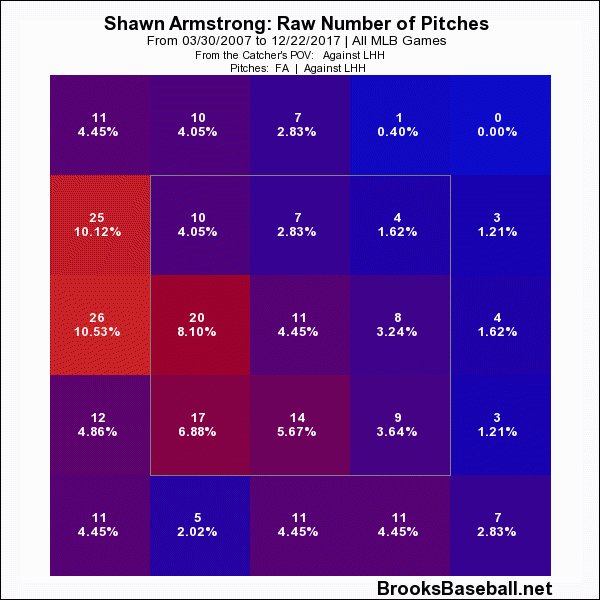

You probably know where this is going. Here’s Shawn Armstrong’s fastball usage to lefties:

Armstrong hasn’t had the same trouble with lefties in the bigs, but then, he’s not exactly maximizing his effective velocity to righties, either. And it’s righties who’ve absolutely killed his fastball. Armstrong is very, very similar in many ways to Vincent, and Vincent has completely changed his approach since he got here, making him a much more effective pitcher overall. It’s possible Armstrong could break free of his statistically-inferred true talent, too, and by following the same general change in approach.

The more I’ve written on this statistically-obsessed blog, the more I’ve come to the idea that it’s these critical shifts in “true talent” are what drive team success. Critics sneer that sabermetrics turns real flesh-and-blood players into trend lines and probability stats, and while that’s grossly oversimplified, there’s…there’s something there. What’s the alternative, shout aggrieved saber-wonks? Rely on how a player looks in uniform? Go by draft order? I’m going to stick to the stats, personally, but I’ll say this: the most important thing the M’s need to do is to have a few of their players make their past statistics utterly irrelevant. Jean Segura did this with Arizona, of course, and Nelson Cruz didn’t become a different player, but became a vastly *better* version of himself in his mid-30s. On paper, this M’s team lacks the talent to compete with either the Astros or Angels. It doesn’t sound like the M’s are going to materially change their talent level between now and April. Ergo, the M’s need to fundamentally change the talent of the guys they already have.

Heading into 2014, Jose Altuve had played 2.5 seasons of perfectly fine baseball. If he was remarkable, it was due to his comically small stature, and the fact that he’d come from nowhere to become a starting player on a team that pretty clearly valued him for his minimal paycheck. In 2014, Altuve had his best season, one that seemed like the logical peak for someone with his (powerless) skillset. A nice BABIP pushed his average way up, and thus Altuve was valuable. Since *then*, however, Altuve’s become something unrecognizable, and something much, much more dangerous. After racking up 21 HRs in his first 3.5 MLB seasons, he’s hit 24 in EACH of the past two. Jose Altuve just slugged .547 on his way to a well-deserved MVP award. Carlos Correa is amazing. #1 draft picks are great, and offer unbelievable talent. Altuve was an afterthought, and then a stopgap, and then a force. No one looking at either Jose Altuve or Jose Altuve’s stats would’ve projected this, but there it is.

You may have seen the photo of Tim Lincecum training about 50 miles north of here at Driveline that’s flown around Baseball Twitter. The great Patrick Dubuque wrote about it at BP here, and he’s right – Lincecum doesn’t *need* to do anything more. His career – his meteoric rise to the top of baseball – was enough, and he has nothing left to prove. We all saw Lincecum’s last appearance in the bigs, pitching for the Angels, in what’s sure to be a tough pub quiz question 10 years hence. He pitched 3+ IP against Seattle, giving up 6 runs on 9 hits, and with an ERA standing at over 9, the Angels released him after that day in August of 2016. The statistical record looks pretty damning: declining velo leading to worse and worse results, and there you go – an early peak, an early fall, and hey, pitchers, amirite? As we’ve seen so often, though, players have much, much more control over their true talent than people like me ever imagined. Does this mean Lincecum’s back? Is Shawn Armstrong the next Nick Vincent? Will Ben Gamel hit 30 HRs? I don’t know, I don’t know, and I doubt it. But if I could make the M’s better than their rivals at any aspect of running a team, it’d be this ability to make a player unrecognizable – to blow the trend and the carefully-constructed scouting report out of the water. The Astros did this with a number of players, and that ultimately meant more to their World Series win than drafting Carlos Correa (though for the record, I’d like the M’s to draft the next Carlos Correa). The M’s trail the Astros in talent, and they need an out-of-nowhere leap in ability from a few of their players. That’d make a fine Christmas gift.

Still More Winter Transactions: Welcome Juan Nicasio and Mike Ford

I don’t think the pixels were dry on my last transactions recap when the M’s made a few more moves, signing RP Juan Nicasio to a two-year, $17 M contract and selecting ex-Yankee farmhand 1B Mike Ford in the Rule 5 draft. Fittingly, the two moves are linked thematically/roster-needs-wise to another of GM Jerry Dipoto’s moves in the offseason: the trade of Emilio Pagan for 1B Ryon Healy. Let’s talk about who the M’s got and why.

Nicasio was an injury-plagued starter in Colorado who pitched in perhaps the worst possible environment for a pitcher with nothing to throw to left-handed batters. He threw a lot of four-seam fastballs with plus velocity and not much else, and he threw a tight slider that occasionally confused righties. He tried to keep lefties off balance with a change up, but batters hit .429 over the course of two half-seasons in 2011-12. Over the course of his long career, batters still have a combined .719 slugging percentage off of Nicasio’s cambio. Moving to the bullpen took some of the pressure off of his change, not least because he could now sit at 95 with his fastball. His slider usage is up over 25%, too, and he’s finally found the confidence to throw it to lefties instead of his sub-par change. All of that pushed his strikeout rate higher, and some work with Ray Searage in Pittsburgh may have helped him keep his walk rate down.

More importantly, as Kate Preusser’s exultant post at LL reminds us, Nicasio’s history as a starter and his usage in LA and Pittsburgh shows that he’s quite capable of pitching multiple innings. This is, then, not simply a standard set-up guy who’ll pitch the 7th or 8th. What he does is replace the remarkably useful Emilio Pagan, who averaged about 1.5 innings per appearance last year. With question marks in the back of the rotation, and with the M’s looking to give more innings to the bullpen in 2018, this ability is crucial, and it’s why LL is so high on Nicasio. Plus, Nicasio’s shift to FB/SL against lefties has transformed him from a guy with awful platoon splits to a guy who ran reverse splits last year.

Nicasio’s K rate dropped a bit last year as batters put his fastball in play more often; their whiff rate was constant, but they hit more of them in fair territory in 2017. Moreover, his K rate against righties has fallen off, from over 10 per 9 in 2016 to under 7 per 9 last year. It’s been steady versus lefties, but small samples and exceedingly volatile HR rates make it hard to know what to expect next year. He was worth 1.4 fWAR in each of the past two seasons, but that masked volatility in runs-allowed, thanks to those crazy HR rates and some issues with stranding runners. To take these in reverse order, Nicasio’s never shown much of an abiltity to strand runners. He was above average last year, but that was the first time in his career you could say that. Yes, it’s not a terribly reliable stat, but Nicasio’s career rate of 70% is straight-up bad, and his since-becoming-a-good-reliever rate is…normal-ish. Great relievers show a consistent ability to strand runners, with your Kenley Jansens and Craig Kimbrel’s averaging 85% or so and getting above 90% with some regularity. Those guys cost an arm and a leg. But even lower-tier guys from Mychal Givens to Addison Reed to Zach Duke to Will Harris can stay in the 80s. Nicasio’s never done that. That’s why his ERA/RA9 has been higher than his FIP in two of the last three years. The M’s need the 2017 version of Nicasio, not the fluke-FIP 2015 version or the 2016 HR-troubled version.

The Yankees, armed with one of the deepest farm systems around, always knew they’d get poached in the Rule 5 draft. It’s why they made so many trades in the run-up to the draft to clear off 40-man spots, like the one they’d just given to Nick Rumbelow. Even with their efforts in November/December, they still lost *4* players in yesterday’s Rule 5 draft, the most of any franchise. With the 11th pick, the M’s selected 1B Mike Ford, a lefty-hitting/righty-throwing guy who’d put up solid numbers in the high minors last year. Similar to fellow new-Mariner Matt Hague, Ford is a control-the-zone star, posting great walk rates but little of the power you associate with the position. He’s projected for an ISO in the mid-150s, and a league average slash line of .241/.334/.398 that looks like a dead ringer for fellow LHB/RH throwing 1B Dan Vogelbach (whose projection is slightly worse at .242/.331/.393). Hague is a righty, and while he doesn’t have a projection at this point, it’d look pretty much the same. All of these guys post very good MiLB walk rates and surprisingly low K rates. Hague had the lowest AAA K% in 2017, while Ford’s done it more consistently. Vogelbach’s 6 months younger than Ford, while Hague’s much older at 32.

The M’s have essentially set up a competition at 1B featuring two righties in Healy/Hague and two lefties in Ford/Vogelbach. Ford goes back to the Yankees if he doesn’t make the club (or come down with a mysterious injury allowing the M’s to DL him), and Hague’s a minor league free agent. But three of these guys have similar skill sets: the precise opposite of Healy’s. I think Dipoto would love to have a bench bat who could spell Healy AND provide a lot more plate discipline than Healy’s going to give you, and thus it’d be nice if this pseudo-platoon guy batted lefty. This competition may be Vogelbach’s last shot to prove that he can contribute to this team, and I could see him moved in the spring if Ford grabs the job. Of course, it’s awfully hard to carry a 1B-only bench bat when you have an 8 man bullpen, as the M’s apparently will. Tying up two roster spots in marginal 1Bs may squeeze more production out of the line-up spot (and it won’t cost the M’s much), but it really makes the 25-man roster a bit more limited.

This gets to the issue with the Healy deal. Not only did the M’s lose a multi-inning RP making league minimum in Emilio Pagan, but the cheap 1B starter they acquired has tons of red flags. In a full year last year, Healy was worth 0.2 fWAR thanks to a very low OBP. His projection for 2018 is 0.2 again. The M’s can’t compete with a below-average-hitting 1B, and that’s essentially where they are. TO blow those projections out of the water, they can either show a hell of a lot more player development chops *at the big league level* than they’ve shown heretofore, or they can supplement Healy’s pop with a healthy dose of a high-OBP platoon partner. No team wants to count on production from a Rule 5 guy; that’s a recipe for disappointment. But if it all goes right, Ford could potentially be a contributor. Is that enough? We’ll see.

The Most Important Mariner

Not content with explaining his process to podcast listeners, Jerry Dipoto made his case that he and his underlings are doing a fantastic job to Larry Stone and the Seattle Times today. Couple a disastrous (and old) 40-man roster, a foundering farm system and an aging core, and Dipoto would argue that the team was worse than the 76-86 record that got Jack Zduriencik fired. The injury wave that broke over the M’s last year hid the progress his re-tooled roster made. Thus, argues Jerry, the team has actually rebuild on the fly, and is preparing to contend.

The M’s lack of activity in free agency is a feature, not a bug. “If you build your club in free agency, you are going down a very long and dark hallway,” he said to Stone. This is an important philosophical point, and one fans often conflate with penny-pinching owners; Dipoto legitimately doesn’t believe in signing huge contracts that have the potential to limit flexibility for years. That’s perfectly understandable, but it means that the M’s need to get star players through other means. The M’s have not been terribly aggressive in international free agency (Ohtani aside), and they’ve resisted trading for prospects, opting instead to trade their own prospects for immediate help like David Phelps. Clearly, the M’s have been very active in the trade market, using it to rebuild their bullpen and their outfield. The result has been a much more well-rounded roster, with the M’s getting production from complementary players in a way they never did under Zduriencik.

The problem is that their core isn’t as productive as it once was. With Felix’s fall from grace, and Robinson Cano’s production becoming a bit more volatile, the M’s problem *now* is that they don’t really have a superstar player. Nelson Cruz, the Nelson Cruz who’ll turn 38 next season, posted the team’s highest position-player fWAR/bWAR in 2017 at around 4. For a DH, that’s spectacular, but if the M’s can’t count on 4-6 from Cano and Felix, they need someone else to step up. The M’s hoped Jean Segura would be that player, as he was coming off a 5 win season in Arizona. Injuries and a lack of power pushed his production around 3, and while his projections look laughably low, it’s perfectly reasonable to think Segura may have peaked in 2016. Dee Gordon’s come close to 5 wins before, but given a position change and a park that severely impacts doubles and triples, it’s going to be tougher for him to get there in Seattle. The M’s need a star-level player and they’re not getting one in free agency, and the minors aren’t going to supply one anytime soon. If the M’s are going to get a star-level player, if they’re going to pack serious production into one roster spot, they need a huge improvement from someone currently on the roster. If the M’s are going to make a playoff run, they’re going to need a big year from Mitch Haniger.

Haniger always seemed like a very intriguing piece of the Segura/Tai Walker trade, and even after fighting through injuries, he posted a .282/.352/.491 line, good for a 129 wRC+. That’s not intriguing, that’s not “a nice second piece,” that’s really good, and there’s reason to believe his trajectory is still headed up. Thanks to a so-so cup of coffee with Arizona and his age, Haniger’s Steamer projections aren’t that great; he’s projected for a 105 wRC+, 4th on the club behind three “core” members of the franchise. If Haniger’s able to maintain his power production and play a few more games, he’s the one non-Cano/Seager/Cruz Mariner capable of producing a 5-6 WAR season.

Wait, wait, what about Segura? Segura could conceivably get there, especially once you factor in his position. To get back to the lofty heights of his 2016 season would require much more gap and HR power than he showed last year. While I’ve been banging on about Safeco no longer being a HR-suppressing park, it’s clearly a different – and tougher – park to play in than Chase Field in Arizona. That park seems to produce an inordinate amount of well-struck contact (whether this is atmospheric, or something to do with the batters’ view, I don’t know), and it’s also got plenty of room for well struck balls to rattle around in. Safeco’s dimensions help with HRs, but make it very hard to get doubles and triples. Add it up, and Segura’s extra-base hit rate went from 9.8% of plate appearances in 2016 to 7.6% in 2017. That’s perfectly fine from your SS! With a couple more HRs or a better BABIP, Segura could easily crest 3.5 WAR, and that would help a top of the line-up that may need help to maintain the solid OBPs they posted last year. I’m glad the M’s extended Segura, but the younger/more complete hitter in Haniger’s the guy they need to make the leap to great player.

What about Paxton? He could easily get to 5 WAR (he was at 4.6 fWAR last year), but it’s going to take something he’s not been able to do in any season, and that’s to stay healthy consistently. Paxton is the team’s best player on a rate basis, but his injury history is impossible to ignore, and he’ll play next season at 29. The M’s need a star player not for a year or two, but for several years: they need a new core to build around. Paxton’s incredible, but tougher to plan around; much of that is simply due to his position, of course. But for all of Dipoto’s moves, the M’s still haven’t solved the question of who the team’s going to build around once Cruz walks at the end of 2018 and Cano/Seager are no longer in their peak seasons. Dipoto’s all but said he doesn’t want to replace these cornerstones through free agency, and Kyle Lewis aside (whose knee injury has proven much more severe than we first thought), there’s really no one in the system capable of becoming such a player. As such, the team desperately needs Mitch Haniger to develop into a star-level player and not just a promising, late-blooming corner OF. Paxton’s incredible, and Segura’s a critical top-of-the-line-up hitter, but Mitch Haniger’s the most important Mariner for 2018 and beyond.

Mid-December Back-of-the-Roster Moves

It’s the middle of December, the Winter Meetings are in full swing, and Shohei Otani – and his slightly dinged-up elbow ligaments – is officially an Angel. What’s a GM to do? Well, depends on the GM, of course, but if there’s one thing we know about Jerry Dipoto, it’s that he believes it’s *always* a good time to work on roster spots 35-40.

In the past few days, the M’s have added several players through MiLB free agency, waiver claims and, of course, trade. It’s somewhat likely that none of them will play an inning for the Seattle Mariners, but you never know, and in the absence of larger moves to talk about, there’s no harm in recapping the newest members of the M’s organization

1: Perhaps the most interesting, at least to me, is ex-Cubs farmhand John Andreoli. Andreoli’s a stocky CF with serious in-game speed; he stole 55 bags in the Florida State League years ago, and while he’ll play next year at 28, he’s still a plus runner. A college teammate of Astros’ CF George Springer, Andreoli’s game was based on slapping at the ball and utilizing his speed. In his draft year at UConn, Andreoli had an ISO of just .031; that’s a grand total of 7 extra-base hits (and zero HRs) in 254 at-bats.

That basic MO carried over into the pro ranks, where he knocked 5 HRs in his first 1,000 or so pro plate appearances, where he supplemented his so-so contact skills with an improved walk rate. Without any power, that was about the best he could hope for – a high OBP, solid defense and baserunning path to 5th OF or pinch runner at the big league level. Somewhere around 2014, though, Andreoli made some pretty big changes to his swing. His ground ball rate dropped, and his fly ball rate surged by about 6 percentage points. This shift in approach had some consequences, and all of them were negative: without power to turn those fly balls into HRs, his BABIP tumbled, and so did his slash line. 2014 was the worst year of Andreoli’s career. Perhaps shockingly, he was undeterred.

Andreoli came back in 2015 and pushed his GB% below 40%, and had the first inklings of in-game power. He knocked 5 HRs that year, which isn’t any good in the PCL, but was as many as he’d had in his entire pro AND collegiate career combined. A high BABIP helped keep his batting average acceptable, and thus he was a fairly productive player, albeit with some warning signs. Andreoli went all-in at this point, and while his average dipped in 2016 thanks to a climbing K rate, he was still a productive player. His speed helped his BABIP, and he swiped 40+ bases to go with an unthinkable-for-Andreoli 12 HRs. He’s no one’s idea of a power hitter, but again, this is quite remarkable considering his own baseline. In 2017, Andreoli carried these swing changes to or nearly to their logical limit. His GB% tanked to below 29%, sending his fly ball rate above 50%. Andreoli’s batted ball profile looks like Trevor Story’s, or a slightly more restrained version of fly ball maven Ryan Schimpf.

Schimpf, despite his tiny size, always showed power through the minors thanks to his approach, and it helped him post a very good season with the Padres in 2016. But his low average (and thus OBP) led the Pads to demote him in 2017, and he’s just moved to the Rays. Schimpf is famous for this approach, but it’s not clear it’s worked for him. Andreoli may be similar – with a K% over 27% in AAA and 14 HRs in a hitting-friendly league, Andreoli and his new approach seems like he’d struggle in the majors. Andreoli’s production surged vs. lefties (Andreoli’s a righty) last year for the first time, and if THAT kept up, you’d at least have a bench-bat/platoon role for him. We’ll see. But it’s an absolutely fascinating transformation, and if he can pair it with improved discipline, you could have something. Even in the meantime, he figures to push Andrew Aplin for Tacoma’s starting CF job, and it may be fun to watch him in the PCL. As a minor league free agent, Andreoli is NOT currently on the M’s 40-man.

2: A more traditional Dipoto-style OF, the M’s grabbed Cam Perkins from the Phillies this past Monday. Perkins came up a corner IF, then moved to the OF corners, but has recently seen some time in center field as well, so you’d figure him as a Ben Gamel-style OF. His strengths/weaknesses look similar to Gamel’s as well. Perkins has generally run good contact rates, and while he doesn’t walk a whole lot, putting the ball in play is a decent way to end up with a good average/OBP (especially in the minors). A righty, Perkins’ limited power means he’s got the same issues as Gamel: not quite enough power for an OF corner, and not quite enough speed/D to play CF. Perkins cup of coffee in Philadelphia this year went about as well as Gamel’s did in Seattle in 2016.

Perkins’ walk rate and power both improved markedly this year, so maybe the M’s think they can coax a bit more out of the 27 year old. A pull-happy hitter with a penchant for infield pop-ups, he reminds me a bit of Taylor Motter, especially when Motter was in the minors, though Motter was better at the plate and offered more defensive flexibility. Still, Perkins is a perfectly cromulent AAA OF, and will help Tacoma in 2017 (if he sticks around). Perkins was on Philadelphia’s 40-man, and as a waiver claim, he’s on the M’s 40-man roster now as well.

3: One question fans have had since the M’s lost out on Shohei Otani was: what are the M’s going to do with their newly-acquired international bonus pool funds? There are a few high profile FAs still around, though teams like the Rangers – who have plenty of $$$ and more of a history in the international market – may be tough competition. Well, today we got a partial answer: they’ll trade it. The M’s took my concept of roster churn somewhat literally and RE-acquired lefty Anthony Misiewicz from Tampa in exchange for a few hundred thousand in…what, it’s not actual money – we’ll call it spending authority. The M’s got Misiewicz back after a few months in the Rays org is exchange for Tampa being allowed to spend more of its own money on international players.

The Rays needed to, because they had a deal worked out with highly regarded prospect Jelfre Marte for more money than the Rays were legally allowed to spend. Marte signed a $3 million + deal with Minnesota this summer, but it was voided shortly thereafter when the Twins detected some sort of vision problem in Marte. The Rays will sign him for $800,000. Somewhat different circumstances, but it reminds me of Christopher Torres having a handshake deal with the Yankees for millions, and, when the Yankees backed out of it, the M’s swooped in and signed him for a fraction of that amount. Anyway, Misiewicz was a late round draft pick out of Michigan State who’s risen to AA thanks to solid control. After an up and down start in the Cal League, Misiewicz had a few great starts for Arkansas, then hit a rough patch, but was solid for the Rays’ southern league affiliate, Montgomery. Misiewicz was drafted in 2015, so is under M’s club control and is not on the 40-man.

I know some wanted the M’s to scoop up more of the ex-Braves prospects that hit the market again after MLB voided their contracts, and Cuban OF Julio Pablo Martinez, so this kind of move may be a bit of a downer. On the plus side, the M’s still have plenty more, and should be able to make very competitive offers to Martinez or whoever else is still available. Marte’s deal with Tampa shows that we’re getting towards the end of the 2017-18 signing period, though – guys who’ve had deals voided due to issues in their physicals, or, in the case of the Braves, by MLB. The best of the Braves haul have already re-signed elsewhere, so while the cupboard isn’t exactly bare, it’s trending that way.

4: Drew Smyly signed a 2-year deal with the Cubs for $10 million ($3m this year, when he’ll mostly be rehabbing from TJ surgery, and $7m the next), with incentives pushing the max value to near $17m. The M’s apparently offered him a 2-year deal, but he’ll head to Chicago.

5: The best name of the newly-acquired M’s goes to RHP Johendi Jiminian, late of the Colorado Rockies org. Jiminian had a forgettable 2017 in AA and AAA, but has a decent fastball and a good change-up.

6: 1B Matt Hague comes to the M’s from the Minnesota Twins system, where he played at the AAA level in 2017. Hague’s from Bellevue originally, so seemed pretty excited about coming to the M’s. Hague’s an extreme contact hitter, with very low strikeout rates and very good walk rates; he’d be the Control the Zone champion of this round of roster moves. He’s had short stints in the big leagues with Pittsburgh and Toronto, but is on a minor league deal with Seattle. The trade off to the elite contact skills is a relative dearth of power, which is an issue for a 1B. His minor league career ISO is just .132, but he also has a career .375 OBP.

7: Returning to the M’s minor league system (non-40-man) are Casey Lawrence, the pitcher the M’s acquired from Toronto and who made several appearances for Seattle, and 2B/IF Gordon Beckham, the one-time White Sox phenom who parlayed a decent season in Tacoma into a September call-up with the M’s. Both players were on the 40-man at some point last year, but both are non-roster players now.

Uh-oh

As usual during a Mariner offseason, I can’t get through one post without huge news breaking. The M’s will not be signing Shohei Ohtani. Ohtani just annouced that he’d be signing with the Angels. I’m typing that through gritted teeth, which is not a metaphor that really works, but… seriously, damn it.

The Angels had acquired some bonus pool funds recently in a deal with the Braves, but had much less to offer than either the M’s or Rangers, the two clubs with (by far) the most. Not only do the M’s miss out, but Ohtani will suit up for the team that’s probably their biggest rival for the 2nd wild card spot, and a divisional opponent. This… this is bad, folks.

As Ryan Divish notes, the M’s can use their newly-acquired bonus pool bounty to sign players through June 15th of next year, but with the J2 crop mostly signed, and with the best players from Atlanta’s rule-breaking haul last year signed to new deals as well (it’s worth remembering that the best of them, Kevin Maitan, ALSO signed with the Angels), the pickings will be somewhat slim. The M’s best options, especially given the fact that they’ve gutted their prospect lists, may be to avoid the J2-eligible signings from Venezuela and the DR and see if there are some intriguing Cuban players looking to make the move north. Whoever they get will both 1) help a seriously depleted farm system and 2) not make this hurt any less.

Mariners Acquire Dee Gordon To Play CF. Are You Not Entertained, Shohei Ohtani?

Two days ago, the M’s traded recent draft pick, a high-floor catcher who’d rank around their 10th-best prospect to Minnesota in exchange for international bonus pool money. Yesterday, the M’s acquired Dee Gordon from the Marlins *to play CF* in exchange for two of their very few remaining prospects, along with an intriguing pop-up arm who did well in Clinton. Again, the M’s got international bonus pool money in the swap – enough to barely overtake the Rangers and become the team able to offer Shohei Ohtani the largest signing bonus.

The Gordon trade is fascinating in and of itself, and reaction to it has been all over the map. But even as we try to process it on its merits, we all have to agree that these moves don’t mean much without knowing where Ohtani lands. If these moves get the M’s over the top, and Ohtani happily signs an obscenely below-market deal with the Mariners, then they’re great. If not, the M’s have spent their remaining prospect assets to add risk.

Risk is the one word that’s come up in pretty much every analysis of this trade. Dee Gordon has played exactly zero innings in the outfield as a major leaguer, and has posted below-average batting lines the past couple of seasons. Of course, that’s not to say Gordon isn’t valuable: he’s been worth 9 WAR over the past three seasons by Fangraphs and just under that by baseball reference. While much of that was the result of his stellar defense at 2B, the M’s clearly think he’ll be able to transfer that defensive skill to CF. The optimistic side of that is raised in the Baseball Prospectus transaction analysis, which notes that even a much slower player like Jason Kipnis had his UZR/DRS/Fielding runs transfer from 2B to CF essentially unchanged; in Kipnis’ case, that just meant a below-average 2B became a below-average CF. So, the thinking goes, now do the same for a well ABOVE average 2B. The experience of Delino De Shields Jr. is a bit more concerning, however. De Shields ranks right with Gordon as one of the fastest major leaguers, and came up as a middle infielder (like his dad), but switched to CF nearer the big leagues. After a poor year in CF, he’s bounced between CF and LF, though to be fair his defensive metrics have improved markedly since 2015. This Fangraphs piece by Jeff Zimmermann examines several other 2B-to-OF position switchers, from Craig Biggio to Ben Zobrist to Alfonso Soriano. Overall, Zimmermann’s pretty confident Gordon can do it, though most of the comps here didn’t play CF. If he can, and if he can add some runs above average, Gordon figures to give the M’s a decent boost above what Guillermo Heredia would give them.

Gordon’s under contract through 2020 for $38 million, so while this is a multi-year deal for a 30-year old player, the outlay isn’t huge by any stretch. But think of what the M’s have done this offseason: they’ve traded Emilio Pagan, their #2, ~#6 and ~#10th best prospects, they’ve traded potential bullpen asset Thyago Vieira. In return, they have an iffy 1B and a CF who’s never played CF before, outside of winter ball. They’ve taken on salary, and traded for a bunch of international bonus pool funding to tempt Ohtani. That is, the M’s have spent money and potentially made their bullpen worse, and while they’re potentially a bit better on paper, they haven’t yet made the kind of move that leaves the Angels/Rangers/A’s in the dust. Everyone knows what THAT move entails, and pretty much every trade I mentioned above has been made with an eye towards getting Ohtani to sign. But in making themselves a more attractive destination, they’ve removed essentially all margin of error. Given where the M’s are on the win curve, you can make the case that the M’s need risk – they need to go for it. But instead of practicing a trapeze act, the M’s have sold off the net, pushed the trapezes a thousand feet up, and now a key member of the act informs you that they’ve never done trapeze before, but they were a great gymnast, and how different could it be?

I don’t think my negative reaction here is the product of overrating the M’s prospects; the M’s top prospects simply aren’t equivalent to other teams’ top 10 guys. While it hurts to lose Nick Neidert, his struggles in AA illustrate that he’s far from a sure thing, and reports of high-80s velo late in the year is…well, that’s Miami’s problem now. But over the past year or two, the M’s have absolutely torn down their top 20 prospect list, and the team isn’t a whole lot better. It’s better, of course, but the question is by how much? It’s fair to point out that many of their former top-20 talents have been DFA’d, so you might as well trade while guys have value. But that gets back to my constant fretting about player development. If the team’s struggling to develop young talent, are they going to get the most out of Ryon Healy (the Vogelbach experience here isn’t encouraging)? The previous front office absolutely bungled player position changes, declaring the actual Chris Taylor unfit for multi-position use, watching Brad Miller struggle in the OF, and tentatively moving Ketel Marte to CF, then pulling him back. This FO should be better (and Gordon’s clearly better), but I’d love to think that their coaches can help ease this transition.

There’s an overarching issue here, I think, that makes me skeptical of the moves we’ve seen so far. Last year, the M’s ranked 5th in walk rate in the AL West, which has 5 teams. They ranked 4th in ISO, and 5th in baserunning runs. The M’s divisional rivals are improving on the offensive side of the ball, and meanwhile, the M’s project as an offense that will be *worse* in on base percentage/walk rate and *worse* in slugging. 144 players qualified for the batting title last year. Of these, Ryon Healy ranked 140th in walk rate. One spot behind him, in 141st, is Dee Gordon. Now, the M’s figure to strike out less, and that’s great, but the M’s have spent the past two years getting absolutely flattened by the home run explosion and how it’s changed the game. This year, the M’s are trying to build a team around balls in play. The M’s tried last year to build a great pitching staff around the idea that you could run a really low BABIP with great OF defenders. They did it, and watched it come to nothing thanks to a flood of dingers. This year, the M’s appear to be betting that with Gordon, Segura and Gamel, they can run a freakishly HIGH offensive BABIP. If league HR rates stay where they are, the same problem may occur: the M’s will have a high average and lots of base hits, but as many or fewer runs than plodding teams like Oakland who’ll rely on the three true outcomes.

I agree with Nathan Bishop that while there’s risk here, there’s also the potential for a big reward. Gordon could take to CF and become a 4-win player. These moves may get the M’s the Ohtani, in which case it’s completely worth it. I think the M’s have made a decisive move to address their need at CF, and it’s a better one than trying to bring back Jarrod Dyson (while Gordon has platoon splits, they’re not as problematic as Dyson’s). Going after Lorenzo Cain would’ve been nice, but I can imagine the M’s want to save some money for a big FA pitcher, and while their 2018-2019 payroll won’t be prohibitive, they are probably already thinking about what it’d cost to extend Ohtani should he sign with them. This is not another bullpen-tweak type move, another of which just happened while I was writing this. But beyond how we value Gordon, the ease of position shifts, or how much more likely the signing of Ohtani just got, I get the feeling the M’s have a very different idea of how to build a great team than I do. That’s OK, they’re the professionals, and I’m the keyboard cassandra with no stake in it. But part of being an M’s fan is that every move comes complete with a tragic precedent. That doesn’t mean the team is doomed, but it means it doesn’t take a leap of imagination to see why it might go wrong. I hope this doesn’t go wrong, and again, if the M’s get Ohtani in part because of these trades, they become retroactively awesome. Strange times we live in.

What We (and the M’s) Mean When We Talk About Spin Rates

One of the best things about this off-season – and admittedly there hasn’t been a whole lot to talk about yet – has been the introduction of the Wheelhouse podcast. It’s essentially a conversation between GM Jerry Dipoto and broadcaster Aaron Goldsmith, and covers the M’s, their focus for the offseason, etc., all with an analytical bent. As such, in addition to talking Shohei Ohtani, the last episode featured a lot of discussion of pitch spin rates, and what the M’s look for in a potential pitcher, and why, for example, Nick Rumbelow or Nick Vincent were guys they acquired. The M’s like high spin fastballs, and they don’t care who knows it.

Now, Nick Vincent checks out as a high spin guy, but if you go to the Statcast data, as Jake Mailhot did in this piece, you find something a bit odd: Nick Rumbelow sure looks like a (well) below-average spin rate pitcher. The podcast also namechecked James Paxton as a high spin guy, but again, he looks below average by Statcast. Andrew Moore, the guy with absolutely elite levels of vertical rise on his fastball – also below average in actual spin rate. What’s going on here?

First, spin and movement are correlated, as spin is what *creates* movement in the first place. No spin, no movement. But if you correlate spin rate and vertical movement of the type measured by pitch fx or Trackman/Statcast, you’ll find that the correlation is pretty darn weak. Again, Andrew Moore had one of the highest vertical movement averages of any pitcher in baseball, but that pure backspin wasn’t the product of elite spin – it was the product of an extremely over-the-top motion that allowed all of the spin he DID impart to work to provide rise. That is, Andrew Moore’s spin was exceptionally efficient – a huge proportion of it went towards moving the ball.

What’s INefficient spin? Doesn’t all spin move the ball? No, that would be too easy. There are two types of spin, as Alan Nathan wrote about in a seminal baseball article at BP, and which I essentially pilfered for this write-up of inefficient spin king Garrett Richards. Transverse spin results in pitch movement. The other type, Gyro or bullet spin (think of a spiral in football), does not. Any pitch has some of both, but the degree to which one pitcher’s fastball is gyro or transverse-heavy varies a great deal. The best example of the *anti-Andrew Moore* – a guy with remarkably LOW spin efficiency – was just in the M’s transaction wire last week: ex-A’s hurler Sam Moll. Moll’s fastball spin rate would’ve been the highest on the M’s, displacing 2017 champions Casey Fien (remember him?) and Ariel Miranda. Moll’s vertical movement is nearly 1 standard deviation *below* average for four-seam fastballs.*

If you imagine two axes – let’s put spin rate on the Y axis and spin efficiency or pure vertical movement on the X axis – you create four quadrants related to spin. In the upper right are the guys with high spin rates and high pitch movement/spin efficiency. Ariel Miranda’s way up in the corner in this hypothetical thought experimenty diagram, with Nick Vincent (whose efficiency isn’t all that remarkable) more towards the middle. In the bottom right are the Andrew Moores, Nick Rumbelows and Ryan Gartons – the spin efficiency specialists. Moll, Rob Whalen and Dan Altavilla are in the upper left, with high spin rates but INefficient spin leading to cutter-like fastball movement. And in the final quadrant, you get the low spin, low movement guys who are more ground ball focused: Felix, Tony Zych, and the pitcher with one of the lowest spin rates in the Statcast database, Jean Machi. It may be better to just show what I mean here:

As Mailhot mentions in his LL piece, it’s possible that Rumbelow’s placement in the Andrew Moore zone is the result of measurement error; maybe Dipoto mentioned him as a spin rate target because in the 2 years since he last pitches in the majors, he’s changed his mechanics and now actually DOES throw a high spin fastball. That’s certainly possible, but the point of this post is to posit that the M’s don’t seem to care so much about spin rate in and of itself. It matters, as many of their targets – from Vincent to Moll to Arquimedes Caminero – may have resulted from spin rate numbers. But it’s clearly not ALL they look at. Moll and Whalen – two high spin, low movement guys with nothing all that pleasing in their stat lines – may have been targeted BECAUSE of their inefficiency, something I mentioned RE: Whalen here. And the team clearly loved Moore (and Paxton, of course) for the movement he generates; they care about Moore’s transverse spin, and DON’T care about a relative paucity of gyro spin. They also went out and acquired Jean Machi last year, a guy with freakishly low spin. Goldsmith asked in the episode if it’s just a matter of being either high or low, and staying out of the middle, and I think he’s on to something, but it makes sense if you view spin as more than just the Statcasted RPM calculation. The M’s want someone with distinctive spin. It can be very efficient, very inefficient, very high, or very low, but they want it out of the middle of the above graphic.

One reason why high spin pitchers may be better than the pure spin efficiency guys is that high spin breaking balls are pretty clearly better. Garrett Richards pairs his cutter-like ultra-inefficient fastball with the game’s highest spinning slider and curve, and batters simply can’t hit them (Richards can’t stay on the field, but that’s another matter). Similarly, Dan Altavilla’s slider has much more break than average, and it was unhittable last year, even as his fastball struggled. Nick Vincent and Rob Whalen also feature high-spin breaking balls. This contrasts with Moore, whose curveball has one of the lowest spin rates on the team. Ryan Garton’s breaker was at least efficient, but neither Rumbelow nor Moore get much movement on their curves, something that helps explain why Moore’s curve was annihilated in the big leagues (in an admittedly tiny sample). With the discussion about the combination of fastball and curve and how one pitch plays off another, a high spin, high movement pitch helps create the separation that Dipoto mentioned.

While they’re ecumenical about spin, they clearly have a favorite outcome, and that’s a fastball up in the zone with high vertical movement. Sorry Sam Moll – the pitch they love is Nick Vincent or Andrew Moore painting the black at the top of the zone with a FB with 10-12″ of vertical rise. That pitch plays into the strategy that I ascribed to Dipoto back in July and that he lays out in detail in the podcast: they want fly balls, and pitchers with lots of movement who can pitch up will generate a ton of them (along with whiffs). That helps the pitchers post consistently low BABIPs, and thus opens a gap between a pitcher’s/team’s FIP and their actual runs allowed. The problem, as we’ve seen, is the home run. Safeco was supposed to ameliorate the flaw in this strategy, but it hasn’t been up to the job, and thus the M’s ultra low-ground ball rate pitchers have hemorrhaged long balls. A good spin rate *is* correlated with improved whiff rates, but at least for the M’s last year, it had ZERO correlation with wOBA on fastballs (it was 0.039). Andrew Moore’s (Ariel Miranda’s) vertical movement wasn’t enough to stave off home runs, and Dan Altavilla’s LOW movement fastball (but high spin rate!) didn’t fare any better.

The M’s need to use this data for more than potential transactions. Most importantly, they need to figure out what kind of HR/FB rate Safeco’s likely to support. In 2017, it’s become too risky to go out and court fly balls, no matter how low of a BABIP you’re able to run. The M’s strategy worked perfectly last year, and they STILL gave up far too many runs. With Mike Leake in the fold, and – fingers crossed – the return of Felix Hernandez, the M’s may give up fewer fly balls in 2018. Now they need to use spin rate information to help tailor their pitchers’ approaches – tweak Andrew Moore’s breaking balls, or see if Miranda can either drop his arm angle a bit (he does this a lot against lefties) or throw a sinker, etc.

* For more on spin and what they call “useful” spin – another way to frame spin efficiency – see this article at Driveline Baseball from Michael O’Connell. It goes into great detail about the differences between pitch types and the specific axis each pitcher’s ball has. They’re able to measure spin directly and isolate transverse spin with Rapsodo technology, which they use to tailor training to each pitcher. Andrew Moore’s a client there, I believe.

A note on data: I pulled statcast spin rates for the 2017 M’s and compared it to movement data from Pitch Info/BrooksBaseball. Whiff rate was calculated from Statcast. All of the data are for four-seam fastballs, so many pitchers had very few (or no) four-seamers to measure. The correlations are NOT weighted by playing time/number of pitches. That means Casey Fien’s handful of pitches counts as much as Miranda’s couple-thousand. The alternative would be to account for pitches, but that just introduces a different kind of bias. I don’t think the way I did it was great, but I didn’t like the alternative. Besides, we’re looking at pitchers’ spin rates and movement, not a game/league average. The low n just means those specific measurements have wider error bars. The correlation of spin and V-Mov was 0.243 and the correlation with wOBA was, as mentioned, 0.039.

Competition to Sign Shohei Ohtani Dropping Like Flies

The clock is running. Teams have made their pitch to Shohei Ohtani’s agent why their organization’s the ideal place for the 23-year old star to develop. Ohtani will soon select a few finalists and have in-person interviews, essentially, that sound like they’ll determine which MLB team gets the ridiculous bargain of Ohtani’s services. Today, we’ve started to learn which teams will NOT make that second round, and the news thus far couldn’t get much better for M’s fans.

The big story is that Ohtani’s not interested in the Yankees. Not only were the Yankees pushing hard for Ohtani, but they’d made a series of trades throughout last season that gave them more international bonus pool space than just about anyone. Ohtani’s timing makes it clear that he’s not deciding based on the biggest payday, but it’s still somewhat shocking that *the Yankees* who, even in the bizarre world of international bonus pools still had a financial advantage, have been shown the door. I’ll take it, of course. The only possible consolation for the Yankees may be the fact that the Red Sox were eliminated as well.

In announcing that his efforts had come to nought, Yanks GM Brian Cashman said that his club had two big strikes against it in Ohtani’s eyes: the Yankees are on the East Coast and they’re a very large market. That’s…that’s encouraging, as the MLB markets on the West Coast tend to be pretty big. The Bay Area is gigantic, even if the population of the cities within it aren’t huge, and in any event, the smallest of those – the A’s – are out too.

Ohtani pretty clearly hasn’t limited the competition to JUST West Coast cities, but plenty of teams have announced that they’re out, and reporters are pointing to both San Francisco and Seattle as finalists. Thus far, the following teams are definitively *out*:

Athletics

Brewers

Cardinals

Diamondbacks

Mets

Nationals

Pirates

Red Sox

Twins

Yankees

Ohtani nearly signed with the Dodgers out of high school, and the Dodgers are still in the hunt, but they can offer just $300,000 in bonus money and play in one of the league’s largest markets. San Francisco and San Diego are strong contenders, but both are coming off abysmal seasons. That said, the former jump right back into contention if they sign Ohtani and Giancarlo Stanton; the Giants have an offer on the table for Stanton now, as the Marlins RF decides whether to bless a move to SF or St. Louis or instead to hold out and try to force a trade to Los Angeles. The M’s can offer a realistic shot at the playoffs in the near term, a small-ish market, non-stop flights to Japan, and have much more to offer in bonus money than either LA or SF. Hell, Ohtani even did some off-season training in Peoria at the spring training home of the M’s (and Padres, who signed an agreement with Ohtani’s NPB team, the Nippon Ham Fighters).

The news today couldn’t have gone much better, though it’s worth remembering that the remaining competition is pretty stiff. San Francisco can point to the development of Madison Bumgarner as a reason to sign, and there’s the matter of three recent World Series titles. Texas is going all-out for Ohtani, as the org has extensive ties to Japanese baseball and landed Yu Darvish several years ago. The Rangers lead the pack in bonus pool funds, too. The Angels seemed like they wouldn’t be able to compete for Ohtani, but their recent trade with Atlanta (who *literally* can’t compete) brought back over $1 M in bonus pool funds, and thus they’re back in the hunt. The Cubs could conceivably compete on their history with pitchers, player development and winning, though they’re not on the West Coast.

While there are a lot of strong teams remaining, today’s news has improved the M’s odds of landing Ohtani significantly. Eliminating the Yanks/Red Sox – both of whom have development advantages over the M’s – as well as darkhorses like the Twins is a big step, and the idea that Ohtani wants to play in a smaller market would give the M’s an edge essentially no other team, with the possible exception of San Diego, could compete with. The M’s cleared the first hurdle and saw some of the favorites fall. They need to be on their game in the in-person interviews, and as Jerry Dipoto said on the last Wheelhouse Podcast, they’re ready for it.

Pre-Thanksgiving Round-Up

Hope you all enjoy the holiday with family/friends. With the end of the Arizona Fall League and the lack of M’s players in the Australian Baseball League, the opportunities to watch live games involving M’s/M’s prospects are few and far between. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t things to talk about.

1: I wanted to follow up a bit on my last post. There were a number of thoughtful replies on Twitter, and I wanted to respond in large part to clarify my own thinking.

The first comes from Driveline Baseball head honcho Kyle Boddy, who wrote:

IMO massive, massive injuries to the pitching staff have significantly contributed to the issue you wrote about – a lot more than I think you assign weight to in the article.

— Kyle Boddy (@drivelinebases) November 19, 2017

I think it's not just (Injuries + Strip Mining); I think the injuries are particularly bad because the Mariners have historically been terrible at developing pitching, so when the depth is brutally bad, the problem is not additive, it is exponentially problematic

— Kyle Boddy (@drivelinebases) November 19, 2017

This is fair; I may be understating the impact of the wave of injuries the M’s suffered through. But the M’s injury woes weren’t exactly unprecedented – other teams – including divisional rivals – lost more players to the DL and/or more games to injury. Kyle’s argument is that the way the M’s were constructed made them *especially* vulnerable to a wave of injuries. My response is that I think we may be arguing the same thing: the M’s lack of development, something he notes in the 2nd reply, is the primary problem here. It’s not the injuries that have led us here, it’s the lack of development.

And that’s why I’m frustrated with the approach of churning through the back of the roster; this is an opportunity for development that the M’s are not taking advantage of. Churning through Costco-packs of Tyler Cloyds/Nick Rumbelows/Ryan Gartons *means* you aren’t building the depth you need if injuries hit. At the very, very least, trading a Zack Littell/JP Sears/Ryan Yarbrough, or pick-your-cast-off-of-choice, seems to show a disconnect between the pro and amateur scouting groups.

As readers like PNW Vagabond noted, the M’s aren’t trading blue-chip prospects here, so the costs aren’t likely to be too onerous (I’m talking about lower-level trades than the Luiz Gohara and Alex Jackson deals, which are going to huuuurt). If the M’s were using this strategy to get better, that’d be one thing – but there’s very little evidence that that’s happening.

To be clear: this is not strictly about trading a low-minors statistical wonder like Sears for an already-debuted, MLB-ready arm. That sort of thing isn’t necessarily bad. The problem is that the M’s have gone the other way on deals like this (Jose Ramirez, who’s been decent for the Braves for 2 years, was traded for Ryne Harper); the problem isn’t an attempt to jump-start development by trading for guys further along their developmental path. The problem is giving *anything* up for the privilege of cycling through guys at the back of the 40-man roster. As I said before, I don’t see any evidence that it’s made the big league team more resilient or more effective.

2: There’s been an interesting, uh, war of words surrounding WAR sparked by the comments of legendary sabermetric writer Bill James and then another brilliant writer, Joe Posnanski. James has a big problem with the WAR metrics (whether Fangraphs’, Baseball-reference’s or Baseball Prospectus’ WARP), which is that, at their heart, they measure RUNS, and then put that run-based metric on a win scale. Crucially, the number of games a player’s team actually won or lost is sort of irrelevant. To James, this is madness: “To give the Yankee players credit for winning 102 games when in fact they won only 91 games is what we would call an “error”. It is not a “choice”; it is not an “option”. It is an error.”

Why would WAR do this? Is this an error? This gets to a very fundamental disagreement over what individual player statistics are supposed to be doing, or as our erstwhile leader here Dave Cameron would say, what question they’re trying to answer. One of the fundamental tenets of sabermetrics, one shown so brilliantly by James himself, is that when we want to compare players, we need to figure out what context we want to include, and what we need to exclude. Team wins are the result of the contributions of many, many players, and they are ALSO the result of luck and chance. James is right that the luck and chance stuff can get lost in WAR – the Yankees runs scored/allowed don’t match up to their actual record, so *10 wins* or so of bad luck just melts away. The converse is to assign it to players based on playing time or whatever, knowing that they may not have had anything to do with it. If your runs (based on linear weights, or some team-specific runs-to-wins converter) MUST align with actual wins, you don’t have a choice.

WAR is trying to answer the question: “About how valuable was this player, assuming he played for an average team in average circumstances?” James is trying to answer this one: “Given that a team won X games, how much credit do each of their players get?” I think many baseball fans are more interested in the latter question, though I don’t know all of them have thought this position through: are we *really* saying that, if Mike Trout’s team was horrible, that he was a lesser player? I disagree with that, but then, I’ve been focused on the first question, not the second. The second really starts to sound a lot like the traditional sportswriting stuff that James made his name arguing against.

Contra James, I don’t think this is diminishing the games themselves at all. Felix – and M’s fans – were punished enough by the actual results of the games in 2010 – he shouldn’t have been punished again by voters. It’s actual results that matter for the playoffs, not pythagorean record (an imputed win percentage based solely on runs scored/runs allowed, and invented by James). But bringing those results into a WAR-type metric fundamentally changes what that metric is for, and not for the better. WAR can always be improved, and I’m not saying it’s foolproof at all. I think a Jamesian measure can have value, and if he wants to argue that Altuve was the deserving MVP, he’ll get no argument from me. But personally, I’m glad WAR is not attempting to bring sequencing and luck into this.

This discussion’s led to some good posts, my favorite of which was Jonathan Judge’s over at BP. Dave’s post at Fangraphs led to a segment on Brian Kenny’s show on MLBNetwork that talked through some of these issues as well. There’s a typically interesting discussion at Tom Tango’s blog where the one person most associates with WAR sets out where he agrees/disagrees with James, noting that James hinted at many of these “issues” with WAR (though stated them much less stridently) a few years ago. Of note is the discussion about WPA. You can create a version of WAR that uses win probability-added and not pure, context-free batting runs. But “Guy” notes in comments that it doesn’t seem fair to only use the WPA values from before an at-bat; after all, at-bats that seemed meaningless at the time can take on more significance later, if a team comes back from a big deficit or if relievers blow a huge lead. Good, nerdy stuff if you’re interested in this debate at all.

3: Game on – Shohei Ohtani will be posted. In recent days, MLB, MLBPA and the NPB were struggling to negotiate a posting process for this year. MLB and NPB had an agreement at one point, but the MLB Players union wouldn’t approve it. Finally, on Monday night, all parties agreed to essentially extend the current process for another year. The negotiation period in which an MLB team tries to sign Ohtani has been cut from 30 to 21 days, but it’s still the same basic system.

That means that the first hurdle to clear to negotiate with Otani is a laughable one: each team puts up a posting fee with a maximum of $20 million, and then Otani decides which team to negotiate a contract with. If he signs one, his old NPB team gets the posting fee from the MLB team. That is, every team pledges $20 million, and only have to pay IF they land Otani. Every team will post $20 million.

In the future, posting fees will be calculated as a percentage of the eventual contract; 20% of the first $25 million, with descending percentages from there. This would allow an NPB team to collect more when a superstar like Yu Darvish gets posted, but crucially, this only applies to over-25 year olds. Because of the change to MLB rules last year, Ohtani isn’t a major league free agent, but is instead subject to the international bonus pools, rules which are meant to apply to 16 year old kids (and are ethically debatable for them). In these situations, an NPB team gets just 25% of an absurdly low cap – perhaps $1 million or so. Ohtani is a black swan, and *because* he’s a black swan, his NPB team and Ohtani himself are forgoing lots of potential revenue. This new agreement seems to lock in that arrangement and ensure that a Japanese talent that somehow gets to free agency before 25 would get far less than he deserves and that the team that developed him would also get hosed.*

After the bizarre posting process, it gets more complicated, as teams negotiating power is constrained by the international bonus pools and the fact that MLB won’t let teams offer more than the standard minor league contract. Teams have every incentive in the world to find loopholes/push the envelope on secret deals or pledges to offer a contract extension if he so much as pitches a solid inning in spring training, but MLB rules prohibit such side deals. Showing clubs that they mean business may be why the league just banned former Braves GM John Coppolella for life and voided the Braves signing of 17 international free agents, including consensus top prospect Kevin Maitan. For years, teams have been cutting side deals with trainers, and punishments for these deals have been sporadic. The Braves seemed to be flagrant about their deals (reportedly signing a 14-year old to a handshake agreement), but the timing here seems important: MLB is watching how teams deal with Ohtani. This means that Ohtani will sign an absolutely absurdly below-market agreement, and MLB will be closely watching to see if teams court him by offering something slightly *less* team friendly. This is the strangest process yet, and now we know we’ll get to see it play out ’till the end.

Happy Thanksgiving!

* International soccer is much more used to players moving from club to club and country to country, so it’s not surprising that some want baseball to adopt FIFA rules giving ‘solidarity’ payments to teams that train players who eventually sign with huge international clubs. Essentially, this would mean earmarking a percentage of a players posting fees to each team that developed him. But as we’ve seen with local star Deandre Yedlin, differences between HS and FIFA laws can make this hard to enforce.

M’s Acquire Ex-Yankee RP Nick Rumbelow in Annoying Trade

The world is awash in outrage, and I don’t want to add to it. Nor do I want to draw any false equivalence between annoying back-of-the-40-man trades and something that really deserves an intemperate response. However mad you can be about trading some low-minors lottery tickets, that’s how mad I am right now. It’s not really about the players involved; Nick Rumbelow may turn out fine. But this is the latest example in a very worrying trend.

Last year, the M’s famously went through 40 pitchers last year, a product not only of injuries (though they clearly contributed), but also of a particular style of roster management. That’s easier to see when you look at AAA Tacoma’s roster, where the Rainiers used an astonishing 52 pitchers in 2017. How can that be when other teams lost more time and/or more pitchers to the DL? Because the M’s, under GM Jerry Dipoto, crank through the bottom of their 40-man roster like no other team.

Because of baseball’s roster rules, these spots at the back end of the 40-man can often be pretty tenuous. Teams roster players to protect them from the Rule 5 draft, for example, but then they may get outrighted or DFA’d once another transaction comes over the transom. Teams with a productive farm system *need* each of those 40 spots, while teams without many prospects might use the waiver wire to fill out the roster instead. The M’s are firmly in the second camp, and thus it’s not a huge shock that they used the 40-man on minor trades and waiver claims. Used well, a team can use these back-end roster spots to build up some depth, especially in the bulllpen. The problem isn’t that the M’s acquire guys like Nick Rumbelow, a one-time prospect who came back strong from Tommy John surgery last year. The problem is that they both pay for the privilege in talent AND then quickly drop guys from the 40-man. The M’s can’t get the most out of any of these live arms, because their hyperactive roster strategy means they can’t actually develop anyone.

Last August, the M’s made a minor deal, trading a couple of lower-level prospects in Anthony Misiewicz and Luis Rengifo to the Rays for C Mike Marjama and RP Ryan Garton. Garton needed a 40-man spot, and eventually pitched a handful of innings down the stretch for Seattle. Garton throws 93+ – nothing overwhelming – with lots of vertical ‘rise,’ has a high-spin curve and an interesting cutter. I don’t want to oversell this; Garton was just outrighted off the roster in October, meaning he cleared waivers. The problem, to me, is that Nick Rumbelow looks an awful lot like Garton. Rumbelow throws 93+ with arrow straight movement and plenty of rise. Seriously, Rumbelow averaged 10.52″ of rise in his 2015 cup of coffee while Garton was at 10.42″ last year. Rumbelow’s slurvy curveball is actually a *low* spin pitch, but his big secondary pitch is a change-up that gets a bit more drop than Garton’s. It’s nothing incredible, movement wise, but it’s helped his K rate against minor league lefties, for what that’s worth.

Rumbelow missed essentially all of 2016 rehabbing his elbow, and only really pitched for half of 2017. To be fair, he put up the best results of his career, limiting hits like never before and inducing some grounders. Dipoto said he thought Marco Gonzales was simply *better* after coming back from TJ, and this may be another case. He may throw the ball better still in 2018 as his surgery fades in the rear view. But he’s 26, and was released by the Yankees not that long ago. Given the Yankee bullpen, he was a marginal roster guy, though of course they added him to their 40-man a few weeks ago. He’s a longshot, but he’s not worthless and may develop in the system. The problem is that the M’s haven’t shown that they have the patience required to actually develop players like this.

James Pazos was solid early on but faded down the stretch. Ryan Garton was intriguing (uh, to me, at least), but if he pitches in Seattle again, he’ll bump Rumbelow or the next Rumbelow from the roster. Meanwhile, all of these moves churn through guys the M’s have drafted and spent some time developing. Rumbelow cost the M’s two low-level pitchers, 2017 draft pick and K-rate king JP Sears and 2016 J2 signing Juan Then. Sears was a blog favorite for putting up video game strikeout numbers in Everett and Clinton. A senior sign out of the Citadel, Sears wasn’t exactly a lock to make the majors. With a 90 MPH fastball, I think a bunch of evaluators might have seen him as a trick-pitch guy, though you simply can’t argue with the results. A longshot like Sears has to open eyes to get a shot, and, well, he opened some eyes. Juan Then was the M’s third-biggest J2 bonus, but put up solid numbers in the M’s Dominican League team while the #1 prospect the M’s signed struggled mightily (he slugged .185) and the #2 prospect was sent off in the Ryon Healy deal. On its own, you wouldn’t bat an eye at two really-far-from-the-majors kids going for a big league ready on-the-40-man player. But the M’s have traded minor league pitchers for Pazos, Garton, Rumbelow, Arquimedes Caminero, Evan Scribner, David Phelps, Shae Simmons, etc. Meanwhile, they’ve been just as active on the waiver wire, bringing in guys like Blake Parker, Evan Marshall, Ryan Weber and a bunch more we’ve all forgotten. Each of THESE moves often bumps someone else off the roster.

There’s nothing wrong with trading prospects to fill big league needs; the last M’s FO failed in part because of their *reluctance* to do so. But what have the M’s really gained in all of this churn? In order to kick the tires on a long list of pitchers, the M’s have essentially ceded the development role in AAA AND traded away a minor league team’s worth of low-minors pitchers. They’ve gotten essentially replacement-level production out of it, though of course guys like Simmons and Phelps are clearly better than that (when healthy). If Dipoto had some special eye for relief talent, that’d be one thing. Outside of Nick Vincent, a cast off from San Diego, the M’s have actually done better with home-grown relievers like Emilio Pagan than they have with trade acquisitions like Chase de Jong or Pazos.

So much of Dipoto’s “buy low” approach depends on a strong player development group that can help correct mechanical issues or improve strength/range of movement. So much of Dipoto’s roster strategy makes that development mission impossible. The M’s bullpen coach Mike Hampton quit midway through 2017. Tacoma operated like an independent league team. The M’s ran through 40+ pitchers. This trade makes me think we’re going to do it all again next year.